Michele Raffin's Blog

March 17, 2015

Bird Talk

Our experience at Pandemonium Aviaries is that birds are great communicators. Therefore, it was with both recognition and appreciation that we found out about Sandra Vehrencamp’s experiments substantiating this.

According to ScienceDaily, Sandra (a behavioral ecologist at Cornell University) goes to various locations to record bird songs and then “plays them back to other birds of the same species to try to determine exactly how birds communicate through their vocalizations.” By doing so she’s not only learns how birds communicate about mating, but also about what they tell each other about their territories, health, and even their age.

Sandra’s work, like ours, is aimed at species conservation. She states that “if we can understand the ecological factors that enhance reproductive success and can link them to conservation, then we might be able to save a species." Turns out those perfectly in tune melodies can do a lot more than bring a smile to our faces and although we may not speak their language, we can sure learn a lot from them.

To read about Sandra’s work go to: http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2008/12/081219172125.htm

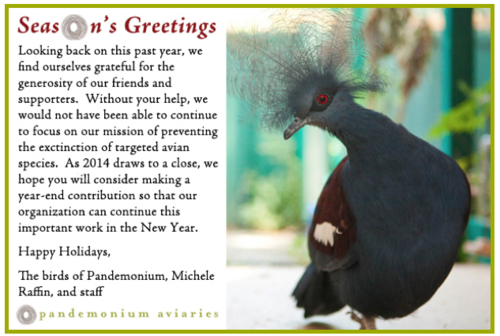

December 19, 2014

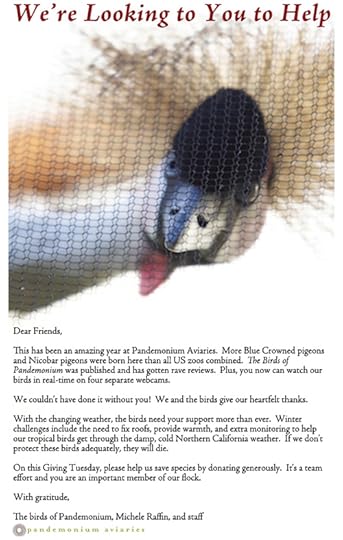

December 2, 2014

Giving Tuesday

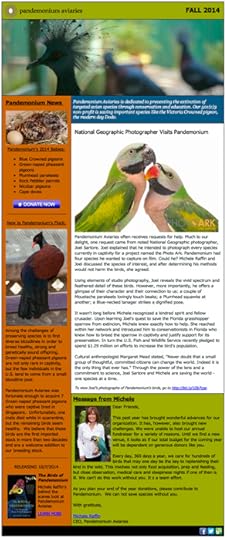

October 3, 2014

2014 Fall Newsletter

Wondering what's been happening at Pandemonium Aviaries? Check out our 2014 Fall Newsletter for a few updates.

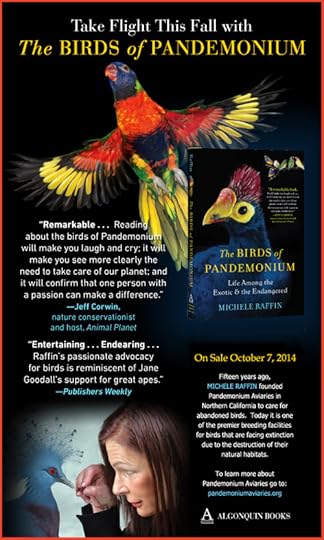

September 16, 2014

New York Times features Pandemonium

Michele's book The Birds of Pandemonium (available for pre-order) is already in the news. An article in the New York Times Home section will appear in Thursday's (9/18/14) paper. There will be a video on the New York Times website featuring Michele and Pandemonium birds.

September 2, 2014

New to Pandemonium's Flock

Among the challenges of preserving species is to find diverse bloodlines in order to breed healthy, strong and genetically sound offspring. Green-naped pheasant pigeons are not only rare in captivity, but the few individuals in the U.S. tend to come from a small bloodline pool.

Pandemonium Aviaries was fortunate enough to acquire 7 Green-naped pheasant pigeons who were captive bred in Singapore. Unfortunately, one male died while in quarantine, but the remaining birds seem healthy. We believe that these birds are the first imported stock in more than two decades and are a welcome addition to our breeding stock.

August 28, 2014

Best Birding Destination

Ever wonder what’s the best birding destination? Well wonder no more. In 2013 Birdingblogs.com held the World Birding Destination Cup, a series of polls to determine the best birding destinations. Coming in on top were Kenya and New Guinea. According to Gunnar Engblom, founder of birdingblogs.com, Kenya (which was ranked first) is a destination “where it is easiest to SEE a lot of birds in a very short [time]”. While the diversity of species seems to have been the criteria that pushed Kenya to the top of the list, Gunnar points out that the reasons birders consider a destination as the “best” varies. Other reasons include how exotic the species are and how safe and accessible a destination is. Regardless of the criteria, we were happy to see that New Guinea (the home of three of our target species - the Blue Crowned pigeon, the Victoria Crowned pigeon, and the Green-naped pheasant pigeon) made the top of the list. We’re hopeful that the more people see these amazing birds in their natural habitat, the more inspired they’ll be to help save them.

Click here to read more about the World Birding Destination Cup at Birdingblogs.com.

November 5, 2013

Effectiveness of Disinfectants on Feathers

There are specialized machines designed to clean and sterilize feathers. Unfortunately these do not match the scale of small organizations and individuals. There is an abundance of information regarding different sterilization methods online. Since the September article on Feather Storage, we [the interns] ran two identical experiments testing the effectiveness of various disinfectants on feathers. Although we were unable to determine which disinfectants were most effective, we did find that 70% isopropyl alcohol was the least damaging disinfectant.

Methods

Twelve Blue and Gold macaw feathers were used. Two feathers were used as the control group. The rest of the feathers were put into separate treatment groups. To gauge effectiveness at freezing we placed two feathers in a plastic bag and kept in a freezer for 24 hours. The remaining eight feathers were placed in groups of 2 and soaked in one of the following solutions: vinegar, Virkon, dish soap and water, or 70% isopropyl alcohol. The feathers were left in the different solutions for 10 minutes. One feather from each of the pairs was then rinsed with tap water.

After air-drying, the feathers were swabbed using sterile swabs. The Petri dishes containing the culture medium were then streaked using the swab. One week later the number of bacteria colonies in each Petri dish was counted. The feathers were visually examined to determine if the solutions damaged the feathers. Changes in color and structure were scrutinized by comparing feathers in treatment groups to the control feathers.

Results

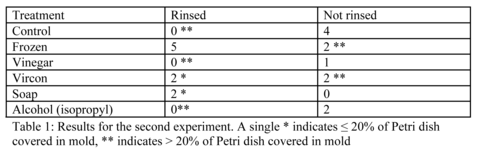

Both experiments are inconclusive for determining the strength of the disinfectants. In the first experiment nothing grew in the Petri dishes. In the second experiment mold grew in all the Petri dishes preventing an accurate count of bacteria colonies.

Treating the feather with isopropyl and freezing does the least damage while vinegar and Virkon do the most. None of the treatments affected the color of the feathers. Soap and water, Virkon, and vinegar caused the feathers to lose their shape.

Discussion

The reason our two experiments did not come up with data is due to preparation. The error in our first experiment was overheating the culture medium. The culture medium we used, agar, needs to be turned into a liquid state from a gel state in order to pour it into the Petri dishes. In the first experiment we used boiling water to heat the agar. Unfortunately this denatured the agar, resulting in no available nutrients for bacteria to feed. Learning from this mistake, for our second experiment we melted the agar using a microwave. The second experiment failed due to lack of a sterile environment. Even though we disinfected all our tools, containers and surfaces before experimentation, we did not work in a sterile environment. If we were to run this experiment again we would need to work in a laboratory setting.

Although no correlation can be found between the amount of bacteria present and the treatment methods, disinfectant causes less damage to feathers than expected. Interestingly none of the disinfectants leached any of the color out of the feathers. Rinsing feathers in either isopropyl or freezing them seems to do the least damage to them.

Blog by Ian Glascock

October 28, 2013

Where Did the Dinosaurs Go?

Bambiraptor, possibly an early link between birds and dinosaurs. Note the proto-feathers covering the animal.

Image credit: http://www.amnh.org

Tyrannosaurus rex foot.

Image credit:

http://jerseyboyshuntdino

aurs.blogspot.com

Rhea foot

Image credit:

http://jerseyboyshuntdino

saurs.blogspot.com

Adult Hoatzin with chick.

Image credit:

http://jerseyboyshuntdino

aurs.blogspot.com

Close-up of chick’s wing with two claws.

Image credit:

http://jerseyboyshuntdino

aurs.blogspot.com

We all know the prevailing theory about how the dinosaurs went extinct. A giant meteor collided with the earth in South America, sending up a huge cloud of dust that obscured the sun’s rays, resulting in climate change that was too much for cold blooded dinosaurs to survive.

But that’s not the whole story. One of the most iconic families of dinosaurs survived, and you see them every day! That family is Dromaeosaur, a group of theropod (bipedal) dinosaurs that includes, among others, Velociraptors and the dreaded Tyrannosaurus rex. But, how did these dinosaurs survive, and where are they today?

They became something else, birds! Evidence is mounting that describes an evolutionary link between modern day birds and Dromaeosaurs, through a common ancestor like Archaeopteryx.

They became something else, birds! Evidence is mounting that describes an evolutionary link between modern day birds and Dromaeosaurs, through a common ancestor like Archaeopteryx.

It is now generally accepted that many Dromaeosaurs had feathers, or proto-feathers, though their function is still debated.

Amazingly, we can still find physical vestiges of their dinosaur heritage in today’s birds. The legs of birds are very similar to Dromaeosaur legs. Birds and dinosaurs are the only obligate bipeds ever, meaning they must walk on their two hind legs. Additionally, running birds like ratites and gallinaceous species have feet that are almost identical to dino legs.

Dromaeosaurs also have modified wrist and arm bones that allow them to make the flapping motion required for flight.

Perhaps the most striking trait that still exists is the remnants of claws on the forearm of Dromaeosaurs. Many galliformes and ratites still have small claws on the ends of their finger bones, but they are obscured by feathers so we never see them. However, one bird still uses these claws, as chicks, to help climb around the precarious branches it is born in.

The hoatzin is native to mangrove forests in the Amazon basin. Learning to fly in the branches of mangroves with nothing to fall into but water presents a problem for young birds. But, by using the claws on their first two fingers, the chicks can fall into the water and haul themselves back out, using their wings like arms.

So it seems the dinosaurs didn’t all go extinct, they just changed. Profound climatic changes killed off the icons like T-rex, but smaller, warm-blooded, feathered creatures were already taking to the air, to eventually colonize the entire world. Some of them survive to this day, filling the sky with their colors and the air with their music.

Cited works:

http://jerseyboyshuntdinosaurs.blogspot.com/2012/07/birds-are-dinosaurs-simple-fact.html

http://www.amnh.org/explore/science-topics/birds-are-dinosaurs

http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/diapsids/avians.html

October 16, 2013

Magnetoception: A Special Sensory Device for Birds

January 2010; Loren Sztajer; via Flickr

Over a large, still body of water, a flock of waterfowl land

with ease on the water’s surface. Each bird keeps its gaze pointed in the same

direction, never looking around, and miraculously the entire flock lands

without a single bump or collision. A team of zoologists from the Czech

University of Life Sciences in Prague set out to find out how these birds

managed to do this. Over the course of a year they observed tens of thousands

of birds from about 4,000 different flocks across 8 different countries. They

found that along with being able to land seamlessly as a flock, birds will

always land in alignment with the direction of the Earth’s magnetic field.

For this to happen, birds need to be able to detect magnetic

fields. This ability is called magnetoception, and has been observed in use by

various vertebrate and insects for discerning direction, altitude, or location.

Studies have shown that homing pigeons use magnetoception to navigate, and that

when a magnet is attached to the bird’s back it cannot properly orient itself

and navigate. It has been long hypothesized that other birds have this magnetic

sense as well, though the mechanism is still unverified. There are two main

hypotheses in regards to how birds are able to sense magnetic fields: they either

use a small piece of magnetite embedded in their beak or inner ear, or they use

a magnetism-sensitive chemical reaction in their eyes, that allow them to

visualize Earth’s magnetic field.

So when a flock of birds approaches a body of water to land

on, the birds will choose to land facing either North or South. How they agree

upon which direction is still not known, but this fact greatly reduces the

chance of collision. It is unknown whether this magnetic sense plays into how

they choose and synchronize their angle of descent, but it has been observed

that this does occur, and further reduces the chance of collision to nearly

zero. Along with being able to locate North with their magnetoception, the

sense also works to help birds and other animals maintain a constant heading in

a particular direction. Migratory birds use this to help with navigation across

large spans of land or water. The uses and mechanism of magnetoception in birds

is still largely unknown, but research is currently being done to explain this

unexplored sensory faculty.