Andy McPhee's Blog

July 1, 2025

Health Risks of Wildfire Smoke: New Study Insights

As I write this nearly 340,000 acres are on fire in the US, with new, large fires reported in Alaska, Idaho, and California. Smoke from those and other recent wildfires move on the wind to areas far away from the actual fires, making a large number of people breathing the smoke.

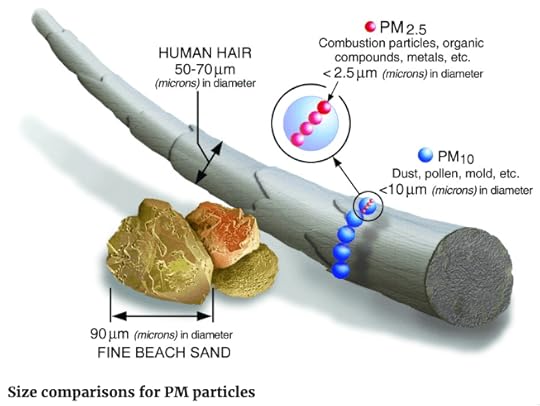

After the many California fires in 2020 more than 36,000 people died from breathing in large amounts of ultrafine particles. Those particles, called PM2.5, are smaller than 2.5 microns in size and are particularly harmful for people with asthma, heart conditions, and the elderly.

Exactly how those particles damaged the body isn’t well understood yet. “We’re in the preschool stage of development,” said environmental epidemiologist Joan Casey of the University of Washington. Long-term exposure to wildfire smoke remains largely unknown.

New StudyBut a new study by researchers at the University of Montana is providing some clues. Immunologist Christopher Migliaccio jumped at the chance to study the health effects of smoke after a 2017 wildfire near Seeley Lake, northwest of Helena. Residents on and near the lake suffered 49 days of smoke-filled air.

Migliaacio and his team studied 95 residents over time and discovered that 10 percent were suffering from diminished lung function right after the fire. That percentage jumped to 46 percent a year later, indicating that health effects take longer to appear than first thought.

Literally toxic airOne of the issues scientists face in understanding wildfire smoke concerns non-organic toxins in the smoke. The Paradise fire last year, for instance, consumed not just forested land but homes, cars, trucks, paints, appliances, electronics, flooring, insulation, water pipes, and many other manmade materials. Toxins released from those items include:

Toxic gases, called volatile organic compounds or VOCsCarbon monoxideNitrogen oxidesLead, zinc, chromium, and other heavy compounds from the burning of vehiclesAsbestosDioxinThe Donora Death Fog happened more than 75 years ago, and still we don’t know as much as we should about the devastating health effects of wildfire smoke. The Clean Air Act, initiated after the Donora disaster, treats wildfire as an “exceptional event,” and so leaves it without regulation.

With wildfires becoming more common, especially in the West, and significant industry-fueled air pollution continuing in many parts of the country, the nation can’t afford any more rollbacks of environmental safeguards. Fight back NOW, before it’s too late.

June 2, 2025

Air Pollution Crisis: The Risks of Regulatory Rollbacks

With half of all US residents breathing increasingly polluted air, the current administration is cutting critical agencies that research, monitor, and regulate air pollution. Does that foretell another Donora Death Fog?

The American Lung Association’s annual State of the Air report is out, and the news ain’t good. The report indicates that 25 million more Americans than those noted in the previous report are being exposed to high ozone or particulate matter. Almost half the nation now breathes polluted air every day.

Thanks for reading Heeding History! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Let’s take a quick look at the history of air pollution control in the United States, where the trouble spots are, and what Trump’s rollbacks might cause over the coming years.

A Wee Bit of HistoryNational attention on air pollution didn’t start until after a deadly fog settled over a small mill town south of Pittsburg for six days, killing 21 and sickening thousands. The town, Donora, has since become a rallying cry to greater control of our air quality.

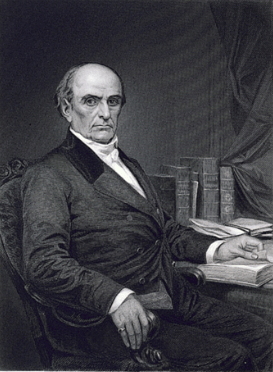

President Harry S. Truman, elected November 2, 1948, just two days after the fog lifted, quickly organized authorized a first-of-its-kind meeting, the United States Technical Conference on Air Pollution.

Truman headlined the conference and extolled the attendees on the dangers of air pollution and the urgent need to learn more about how pollutants affect the body. He said at that meeting:

Air contaminants exact a heavy toil. They destroy growing crops, damage valuable property, and blight our cities and the countryside. In exceptional circumstances, such as those at Donora, Pennsylvania in 1948, they even shorten human life. We need to find out all we can about the relationship between air contaminants and illness.

The act that came out of that meeting, the Air Pollution Control Act of 1955, led directly to the law we know today as the Clean Air Act.

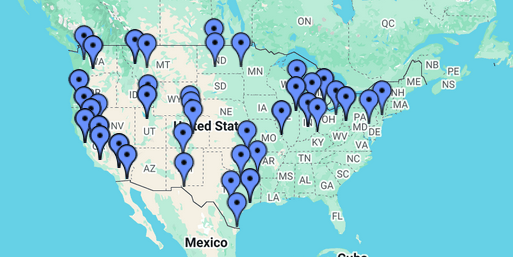

Trouble SpotsFor the last few decades several areas have consistently demonstrated high air pollution levels, particularly along the lower Mississippi River, throughout the mid-Atlantic states, and along the entire West Coast.

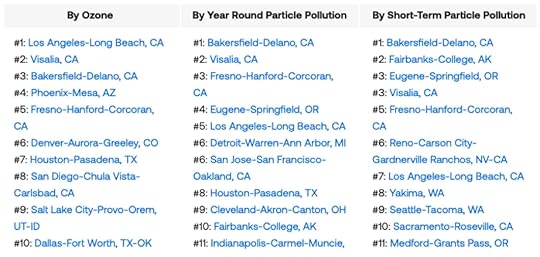

Top 10–11 most polluted cities for three main pollution categories include:

What the Future Holds

What the Future HoldsAt this writing the Trump administration has canceled climate research programs, fired climate scientists at NOAA and the Department of Agriculture, and deleted climate datasets. It has rolled back many EPA regulations and is looking to eliminate many EPA scientists.

Will these drastic changes lead to another Donora? I think it’s possible, but unlikely. Donora was a kind of perfect storm of a prolonged fog over a steel and zinc factory town located in a steep-walled valley and with owners who didn’t full grasp (or didn’t care to) the dangers of air pollution at the time.

Factories throughout the US have been retooled to reduce the pollutants they spew, and the topography of most high-pollution areas probably won’t allow such a dense concentration of toxins to hang in the environment too long.

But all of those rollbacks and cuts will without question lead to our having less knowledge about our environment, less control of the worst polluters, and a population progressively more endangered from pollutants in the air.

No, the news from the State of the Air report ain’t good. It ain’t good at all.

October 22, 2024

Why I Love Moral Dilemmas

Apparently I’m most interested in writing true stories about events that, in essence, center on moral contradictions.

My first trade book, Donora Death Fog: Clean Air and the Tragedy of a Pennsylvania Mill Town, was about a group of people forced to endure a disaster that could have been foreseen but who largely supported the corporation that caused that disaster to begin with. Many of the good people of the Monongahela valley refused to believe that their employer, US Steel, could possibly have had something to do with a six-day smog in 1948 that killed twenty-one of their neighbors. They just didn’t want to believe it.

As I related in the book:

“Rongaus” refers to Dr. William Rongaus, the most outspoken critic of the zinc and steel mills during and after the smog.

“Rongaus” refers to Dr. William Rongaus, the most outspoken critic of the zinc and steel mills during and after the smog.How can you find fault with a company critical to the outcome of WWII and that pays you to work even though working for that company can kill you, maim you, or give you life-threatening cancer?

My forthcoming book, The Doctors’ Riot of 1788: Body Snatching, Bloodletting, and Anatomy in America, centers on a similar moral dilemma. From the 1700s until the passage of the nation’s Uniform Anatomical Gift Act in 1968, physicians and anatomists have tried to balance the need to obtain fresh cadavers, so their students could learn the fundamentals of anatomy, with the community’s aversion to the practice of body snatching and its heartfelt desire to respect their dead.

I write in the first chapter, “Is it moral to dissect a body for the betterment of medical students if that body was illegally obtained? Said another way: Does the future health of the living outweigh society’s need to maintain the dignity of the dead?”

That’s just the kind of moral morass I love to delve into, I guess, a enlightenment that came only last night as I was lying in bed, next to my beautiful, sniffling wife. (She has a cold.)

Anyway, here is the cover for my new book, due out next fall from Prometheus Books, an imprint of Globe Pequot Press.

If you'd like an email announcement of its impending publication, shoot me an email at andymcpheebooks@gmail.com.

If you'd like an email announcement of its impending publication, shoot me an email at andymcpheebooks@gmail.com.

September 6, 2024

Enter My Goodreads Giveaway!

Donora Death Fogby Andy McPhee

Donora Death Fogby Andy McPheeGiveaway ends September 26, 2024.

See the giveaway details at Goodreads.

May 12, 2024

Why It Wasn’t Just Gray’s Anatomy

No, not the TV show, the anatomy textbook. Known far and wide as Gray’s Anatomy, and still published today by Elsevier, Henry Gray could not have found success without his artistic partner, Henry Carter. Here’s their story.

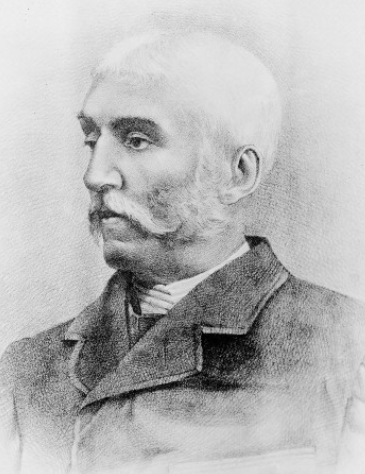

Henry Carter self-portrait

Henry Carter self-portraitHenry Vandyke Carter had been keeping a diary since he was fourteen. He was now twenty-four and an anatomy instructor at Saint George’s Hospital Medical School in London. He had been lamenting in the fall of 1855 about an indifference he had been feeling about his work and faith. “Very little irritability,” he wrote, “and still lament this disintegration of purpose, and act as much in regard to religion as to study. This latter troubles me very much, for I am doing nothing—nothing worth[while] and so this faltering.”

Carter might have still been troubled when he was approached a few weeks later by another anatomy instructor at Saint George’s, Henry Gray, who proposed a joint writing project. Carter had worked previously with Gray on a book about the spleen, with Gray describing the organ and Carter creating the illustrations. Carter possessed considerable talent as an artist, a trait no doubt passed along from his father, Henry Barlow Carter, a marine artist of some repute. Carter had been teaching alongside Gray for some time but considered the man a “snob.” Carter had been paid a pittance for his spleen illustrations, so he probably listened with a skeptical ear as Gray outlined his new, far more ambitious plan.

A photo taken in 1860 shows a dissecting room in Saint George’s Hospital. Henry Gray, in a dark suit, sits in the first row, third from left. Henry Vandyke Carter had left London when the photo was taken and was then working at Grant Medical College in Bombay, India. Courtesy of Wellcome Collection.

A photo taken in 1860 shows a dissecting room in Saint George’s Hospital. Henry Gray, in a dark suit, sits in the first row, third from left. Henry Vandyke Carter had left London when the photo was taken and was then working at Grant Medical College in Bombay, India. Courtesy of Wellcome Collection.Carter described the discussion this way: “Little to record. Gray made proposal to assist by drawings in bringing out a Manual of Anatomy for students: a good idea but did not come to any plan.” Carter considered the idea “too exacting.” Gray persisted in courting the illustrator, however, and Carter, who needed money, finally relented. Carter drew the first few illustrations on paper, a process so cumbersome and time-consuming that he switched to drawing reverse images on woodblock. Gray for his part provided clear, precise, and exhaustive descriptions of individual body parts. Consider this unusually brief (for Gray) description of the middle fossa, a butterfly-shaped depression at the base of the skull:

The Middle Fossa, somewhat deeper than the preceding, is narrow in the middle, and becomes wider as it expands laterally. It is bounded in front by the posterior margin of the lesser wing of the sphenoid, the anterior clinoid process, and the anterior margin of the optic groove; behind, by the petrous portion of the temporal, and basilar suture; externally, by the squamous portion of the temporal, and anterior inferior angle of the parietal bone, and is separated from its fellow by the sella turcica. It is traversed by four sutures, the squamous, spheno-parietal, spheno-temporal, and petro-sphenoidal.

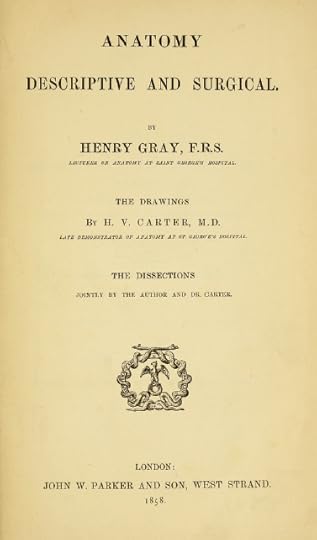

Three years later Anatomy: Anatomy Descriptive and Surgical, was published, a volume with a deep, burnt sienna cover that would almost immediately become a bestseller throughout Europe. The book, that “too exacting” an idea, contained three hundred and sixty-three of Carter’s illustrations, each one meticulously detailed and rich in labeled parts. The anatomy texts of the time, particularly Quain’s Anatomy, couldn’t compete with Gray’s Anatomy, which offered larger pages, better organization, and far fewer cross references, which Quain’s had infused throughout.

On publication the Lancet wrote, “[The book] is a work of no ordinary labour, and demanded the highest accomplishments, both as anatomist and surgeon, for its successful completion. We may say with truth, that there is not a treatise in any language, in which the relations of anatomy and surgery are so clearly and fully shown.” Initial sales were so healthy that a second edition was planned almost immediately and published in 1860. In the intervening year renowned Philadelphia publishing house Blanchard and Lea (later Lea and Febiger) published a version for the United States, and that too became a bestseller.

Anatomy was renamed in 1938 to Gray’s Anatomy and is more commonly known today as simply Gray’s. The text has been in continuous publication for more than 165 years, mushrooming over that time from an initial six by nine inches to nine by twelve, from 782 pages to an enormous 1,606 pages, from just over three pounds to more than ten, and from about $5 in 1860 to more than $240 in 2023.

Together Gray and Carter produced a work of extraordinary consequence. Hundreds of thousands of medical students the world over have used Gray’s as an intimate part of their education and subsequent practice. Even today Gray’s can be found in virtually any college or university library and remains a foundational resource for human anatomy education. “Gray’s Anatomy is so well known today,” wrote Ruth Richardson in The Making of Mr. Gray’s Anatomy, “that it’s hard to imagine a time when it didn’t exist: that is, before its text had been written, before its famous illustrations had been drawn, before the contract with its publisher had even been agreed.”

Tragically, Carter perished from tuberculosis in 1897. He had lived a difficult life, and his name had only belatedly been added to the authorship of the textbook that changed medical education. Gray had been caring for his 10-year-old nephew with smallpox and also contracted the disease. His nephew recovered, but Gray did not. He died in 1861 at age 34.

October 23, 2023

What Happened to Residents’ Health Long After the Donora Death Fog?

Our scientists tell us that the Donora episode was a rare phenomenon. We hope and pray it will never recur. This study by the Public Health Service into the Donora episode, the most exhaustive ever made on a problem in air pollution, is a step toward positive assurance that such a thing will not happen again.

Oscar R. Ewing, Director of Federal Security Agency (now the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services)

Such were the words introducing a study of the health of Mon Valley residents ten years after the Donora Death Fog, a tragedy of historic proportions. Six days of deadly smog in late October 1948 in Donora, a small mill town in southwestern Pennsylvania, served as a wakeup call for US politicians, business owners, and the public at large about a dangerous and growing problem —air pollution.

Harry Truman

Harry TrumanThe tragedy moved President Harry Truman, elected November 2, just two days after the smog ended, to create the first-ever national conference on air pollution, the United States Technical Conference on Air Pollution. The event was held at the Wardman Park Hotel in Washington, DC, on May 3–5, 1950. Five hundred representatives from a cross-section of industries attended the event to discuss air pollution and set up ways to study its effects on health.

“It is my hope,” said Truman, “that the exchange of specialized information which takes place at the [conference] will contribute toward prompt initiation of corrective measures.”

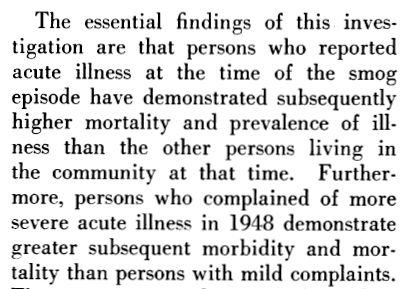

Physicians, scientists, and officials of the US Public Health Service ended up completing a follow-up study on Donora ten years after the smog, and in it they they examined mortality and morbidity rates for cardiovascular and respiratory illnesses in residents who survived the smog. They found that the sicker a person was during the smog, the greater the likelihood that they would suffer heart or lung disease or die.

Excerpt from USPHS study

Excerpt from USPHS studyThe researchers were unable, however, and possibly unwilling, to identify specific toxins responsible for the increase in disease and death rates among residents.

Unable, because there simply wasn’t known about the health effects of air pollution in general to identify which toxins produced which diseases. “Although the Donora data do point to some effects on the cardiorespiratory system,” the researchers wrote, “they do not provide the means for relating particular pollutants to specific symptoms. Without such specific information it is difficult, if not impossible, to distinguish between those persons whose disease conditions conceivably could be due to exposure to air pollution from persons whose disease conditions are due to other factors.”

Perhaps unwilling, because even if the researchers harbored strong suspicions about the causes, to put to paper those suspicions would likely have caused damage to their careers. One didn’t criticize industry like that, not at that time and certainly not behemoths like US Steel, which owned all of the mills in Donora.

In the 75 years since the Donora Death Fog happened and the 65 years since the follow-up study there have been hundreds, if not thousands, of studies on the health effects of air pollution, and yet significant air pollution continues to exist around the world, including here at home. The most recent State of the Air report from the American Lung Association indicates that the top ten worst cities for air pollution, in this case yearly particulate matter, are:

1 (tie): Bakersfield and Visalia, CA3: Fresno-Madera-Hanford, CA4: Los Angeles-Long Beach, CA5: Fairbanks, AK6: Sacramento-Roseville, CA7 (tie): Medford-Grants Pass, OR, Phoenix-Mesa, AZ, and San Jose-San Francisco-Oakland, CA10: Indianapolis-Carmel-Muncie, IN Smog over downtown Los Angeles. Photo taken May 15, 2023. (KTLA)

Smog over downtown Los Angeles. Photo taken May 15, 2023. (KTLA)Please remember the lessons of the Donora Death Fog and support clean air legislation whenever it comes up, nationally or in your home state.

To learn more about the worst air pollution disaster in US history, check out my book, Donora Death Fog: Clean Air and the Tragedy of a Pennsylvania Mill Town.

October 14, 2023

From Boom to Bust: What Happened to Little Webster?

Cuddled along a bend in the Monongahela River in southwestern Pennsylvania, across from the industrial town of Donora, Webster once boasted a population of about two thousand. Anyone traveling up the Mon around the turn of the twentieth century would have seen a charming village at the base of steep farmland rising over well-kept homes. A coal tipple stood along the river as well, ready to plunk its cargo into awaiting train cars. “Yards were separated by white picket fences,” wrote journalist Scott Beveridge, “and most contained lush orchards and flower and vegetable gardens.”

Daniel Webster

Daniel WebsterNamed for Daniel Webster, the renowned orator and senator, Webster was large enough to have its own bank, train station, and post office building. There was also a sizable flour mill at the corner of Third Street and Webster Hollow Road. The Webster Roller Flour Mill produced King Midas flour and “feed, hay, and grain of all kinds,” with “fancy Minnesota flour a specialty.” Folks from Pittsburgh and the surrounding area would often travel to Webster for weekend getaways. They would stay at one of the town’s four hotels, including one at the corner of Second Street and Webster Hollow Road, which had a classy restaurant complete with spindle-back chairs, smooth white tablecloths, and a central fireplace below a doily-covered mantle.

Civil War hero John Vogel owned the Union Hotel, along with about a dozen beautiful buildings in town. The town’s quaint shops, respected hotels, and stately mansions made Webster one of the area’s “destination towns” before that term was ever invented.

And then came 1915.

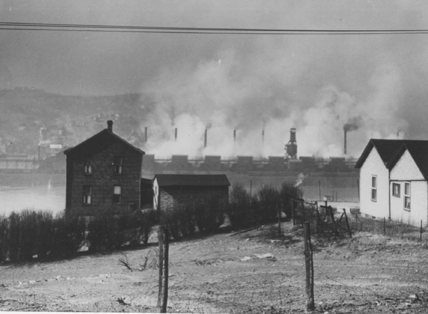

That was the year the Donora Zinc Works was built and began producing zinc, in the process sending thick plumes of toxic gases and particulate matter into the air—all day, every day. Prevailing winds tended to blow the smoke eastward over Webster. The toxins decimated the Webster hillside, burned the paint off houses, and left the orchards and gardens dust-bound.

Smoke from the zinc factory as seen from Webster

Smoke from the zinc factory as seen from WebsterThe wealthiest residents left first. “Webster’s riverboat captains,” said Beveridge, a long-time Webster resident, “having witnessed how these giant mills had damaged other farms along their travels, immediately put their estates on the market. Anyone else with enough money soon followed their lead.”

Webster was finished.

After the zinc mill closed in 1956 and the toxins no longer blew over Webster, the vegetation came back. The hillside today is covered in forests and fields, but the town’s population has never recovered. Seventy-eight people now call Webster home, with that number declining year over year.

When people discuss the tragedy of the Donora Death Fog in 1948, they shouldn’t forget the more than a century-long tragedy of little Webster.

To learn more about Webster and the Donora Death Fog, read my book!

Donora Death Fog: Clean Air and the Tragedy of a Pennsylvania Mill Town

September 30, 2023

What Happens to Residents’ Health When a Coke Plant Closes?

Just south of Careopolis, Pennsylvania, the Ohio River splits at the northernmost tip of a long skinny island and joins together again about five miles later. The island, Neville Island, contained at its southernmost tip the Shenango Coke Works, a sprawling industrial complex built around 1930. Shenango processed coal for steel mills and had been spewing benzene, hydrogen cyanide, and hydrogen sulfide for decades.

Having finally outlived its usefulness Shenango ceased operations in 2016, its buildings imploded in 2018. Five years later researchers made a stunning, unbelievable, completely and utterly unexpected discovery.

I jest.

The research team from New York Univeersity discovered pretty much what they expected to, that the closure of the coke works would lead to decrease in air pollution in the area and a significant reduction in the number of emergency room visits. Wuyue Yu, one of the NYU researchers, said of the study, “It was a natural experiment. The only factor that has changed in their life is the closure of this complex.”

The study found that sulphur pollution dropped an astounding 90 percent. Meanwhile emergency room visits for cardiovascular issues dropped more than 60 percent, and the rate is still dropping.

Scientists equate the improved health in the area to someone who quits smoking. George Thurston, professor of Environmental Medicine and Population Health at NYU’s School of Medicine, explains, “Immediately, they (experience) less coughing and hacking. But then over the long term, you know, their lungs get healthier.”

The findings didn’t surprise scientists. Lucas Henneman, an environmental engineering professor at George Mason University, said, “We’ve established evidence going back decades that emissions influence air quality, air quality influences health,” said Henneman, who was not involved in the study. “When we can show..there are clear benefits when we reduce air pollution to health. I think that sends a pretty powerful message that these interventions that we’ve taken on polluting facilities work.”

And it’s all due to the after effects of the Donora Death Fog in 1948, which spurred the first clean air act, the Air Pollution Control Act of 1955. The twenty-one people who perished in the smog did not die in vain. To learn more about the smog, the worst air pollution disaster in US history, check out my book, Donora Death Fog: Clean Air and the Tragedy of a Pennsylvania Mill Town.

What Happens When a Coke Plant Closes?

Just south of Careopolis, Pennsylvania, the Ohio River splits at the northernmost tip of a long skinny island and joins together again about five miles later. The island, Neville Island, contained at its southernmost tip the Shenango Coke Works, a sprawling industrial complex built around 1930. Shenango processed coal for steel mills and had been spewing benzene, hydrogen cyanide, and hydrogen sulfide for decades.

Having finally outlived its usefulness Shenango ceased operations in 2016, its buildings imploded in 2018. Five years later researchers made a stunning, unbelievable, completely and utterly unexpected discovery.

I jest.

The research team from New York Univeersity discovered pretty much what they expected to, that the closure of the coke works would lead to decrease in air pollution in the area and a significant reduction in the number of emergency room visits. Wuyue Yu, one of the NYU researchers, said of the study, “It was a natural experiment. The only factor that has changed in their life is the closure of this complex.”

The study found that sulphur pollution dropped an astounding 90 percent. Meanwhile emergency room visits for cardiovascular issues dropped more than 60 percent, and the rate is still dropping.

Scientists equate the improved health in the area to someone who quits smoking. George Thurston, professor of Environmental Medicine and Population Health at NYU’s School of Medicine, explains, “Immediately, they (experience) less coughing and hacking. But then over the long term, you know, their lungs get healthier.”

The findings didn’t surprise scientists. Lucas Henneman, an environmental engineering professor at George Mason University, said, “We’ve established evidence going back decades that emissions influence air quality, air quality influences health,” said Henneman, who was not involved in the study. “When we can show..there are clear benefits when we reduce air pollution to health. I think that sends a pretty powerful message that these interventions that we’ve taken on polluting facilities work.”

And it’s all due to the after effects of the Donora Death Fog in 1948, which spurred the first clean air act, the Air Pollution Control Act of 1955. The twenty-one people who perished in the smog did not die in vain. To learn more about the smog, the worst air pollution disaster in US history, check out my book, Donora Death Fog: Clean Air and the Tragedy of a Pennsylvania Mill Town.