Vedat Milor's Blog

November 21, 2025

From Coutanceau To Roellinger To Couillon: A Trip Defined By La Marine

This trip along the Atlantic and Breton coast had a clear gastronomic purpose: to visit three well-established names of coastal cuisine, Hugo Roellinger in Mont-Saint-Michel Bay, Christophe Coutanceau in La Rochelle, and Alexandre Couillon in Noirmoutier.

All three chefs interpret the sea through their own lens. Only La Marine offered an experience powerful enough to leave a profound and lasting impression.

Christophe Coutanceau delivered technique and consistency, but the overall experience lacked the emotional and gustatory impact one expects at this level.

Hugo Roellinger, despite the reputation and family heritage, felt less compelling than expected, especially when compared to his father’s emblematic dishes such as the iconic agneau aux épices, a dish that Vedat Milor still recalls with admiration. In fact, at Roellinger’s, we enjoyed more their bistrot Le Cancale, not the gastronomic restaurant.

Alexandre Couillon, however, stood apart. His restaurant La Marine was above the rest, because it offered something neither Coutanceau nor Roellinger achieved on this trip: a complete, coherent, place rooted culinary identity from start to finish.

The Experience Begins Before The MealOne of La Marine’s many strengths is that experience begins before entering the dining room. We were led to a projection space, where a short film immersed us in Noirmoutirer’s tidal life, algae fields, fishermen, violence of storms, quite of dawn and beauty of coastal ecosystems.

For a chef so deeply rooted in Noirmoutier, this introduction is not theatrical, it is contextual. A way of telling: listen first, then taste.

The dining room, recently renovated with taste and elegance extends the same philosophy. And at the heart of the room is Mme Céline Couillon whose master of service is integral to the experience. She leads with precision and warmth, just perfectly aligned with the spirit of the cuisine. Her presence is one of the restaurant’s great strengths.

The Menu Biodiversite MarineThe menu traces a path through Noirmoutier’s maritime ecosystem, moving from delicate coastal flavors to deeper, more intense marine notes before returning to softly to land. A cuisine of precision, purity and place.

Amuses bouches

The amuses set the stage for what will unfold later. Delicate but full of flavor, plenty without being excessive and well thought out. Instead of “tisane” we are served a bouillon of shrimps with fresh verbena. We were also served various crustaceans in little paper thin tarts and seaweed (algues) dressed with pinenut vinegar encased in bucket shaped mini biscuits. Next, came young fennel from the garden with spider crab and burnt lemon cream. Finally, we were served sunchokes with cacao, mushrooms and hazelnut.

Saint-Jacques, Lait D’amende Et Encornets

The Saint-Jacques is handled with precision, warmed on the outside and the center raw. The texture is firm and sweet. The almond milk is well calibrated, light, discreetly nutty, and not over reduced. The squid strips give the dish the necessary marine contrats. The only strong element is the black acidic condiment, which is correctly dosed and prevents the dish from falling into blandness. A technically sound opening course with clean flavors.

Maquereau, Betterave Et Lait De Persil

The maquereau is impeccably fresh and cooked skinside to achieve crispness without drying the flesh. The parsley emulsion brings lift and a subtle acidity, and the beetroot sorbet, cold, sweet and earthy works better than expected with the grilled fish. The balance between fat, acidity and earthiness is well thought out. A dish that demonstrates Couillon’s ability to work with so-called “humble” fish without masking their character.

Homard, Caviar, Un Flan Au Bouillon De Crabe Vert, Halophytes

The cooking of the homard is exact, firm but tender texture. The flan underneath is extremely soft and serves as a structural link rather than aromatic element. The green crab broth is intense, saline, and iodine driven. It gives the dish its identity. Julien Dumas (Zostera in Paris) loves also using that sauce. The caviar integrates seamlessly into the sauce and acts more a seasoning amplifier than as a luxurious topping. A complete and expressive dish, one of the most flavorful in the menu.

Laitue, Braise Et Un Crème D’herbes Potagères Et Jus D’oignons

This is a simple dish on paper, but very well executed. The grilling brings slight bitterness and depth. The herb cream adds freshness, and the onion jus gives a discreet sweetness that rounds the dish. The addition of seaweed and small herbs add aroma without cluttering the plate. A successful vegetable course that remains flavorful and structured.

Huître Grille, En Paquet De Feuilles De Choux

Grilling alters the oyster’s texture and dims the raw iodine intensity. The cabbage leaf gives softness and a vegetal element. The foam is light and neutral. The dish is intentionally restrained and offers a gentler expression of oyster. Technically correct, though less expressive than other courses.

Lieu Jaune, Courge Et Poire, Un Petit Lait Au Vinaigre De Sureau

The cuisson of the Lieu jaune is excellent: moist, firm, and uniform. Serving the skin separately as a crisp roll is a clever way to preserve texture without compromising the fish. The whey sauce brings light acidity, while the darker reduction provides the depth often mission from lean white fish. The grilled coastal green adds salinity and structure. A clean, precise dish built around product quality rather than complexity.

Barbe, Blettes Ligotées, Un Jus De Tête Et Œufs De Poissons

A more assertive dish. The fish-head reduction gives a gelatinous, strongly marine sauce. The chard contributes a slight bitterness and vegetal length. The roe adds salinity. This is the most intense fish preparation of the menu, and one that shows Couillon’s confidence in working with concentrated marine flavors.

Laitue De Mer, Sorbet, Fouet Des Sorcières Et Sarrasin

The sorbet is cold, saline and discreetly bitter. The buckwheat underneath provides warmth and crunch. It resets the palate effectively without sweetness and prepares the diner for the shift toward dessert. Very functional and well executed.

Pomme De Terre, Un Crème Onctueuse Et Noissette

A smooth potato cream shaped into a sphere, lightly sweetened. The texture is extremely soft, almost mousse-like. The hazelnut adds arome and a bit of contrast. A warm and quite dessert that avoids excessive sugar.

Our Wine Choices

Our Wine ChoicesThe wine at La Marine is handled with competence and a clear understanding of the restaurant’s culinary philosophy. With the pairing, we aimed to respect the purity and salinity of the dishes by avoiding oxidative or heavily oaked wines that would overpower.

Frederic Savart – Le Mont Des Chrétiens 2019

This champagne was an appropriate choice for the opening sequence. Its acidity and restrainted soage supported the amuse bouche and first dishes. Compared with Savart’s Eceuil-Trépail cuvée, this bottle shows more structure and less aromatic charm, but the precision of its profils matched the minimalistic direction of the first dishes.

Les Vignes Oubliées – Saint-Jean De Bébian 2017 (Languedoc Blanc)

This wine offered more width and texture, which worked well with the lobster and the green crab broth. The dish has strong iodine depth, and this wine’s balance of bitterness and mediterranean herbs held up to it.

Albert Boxler – Pinot Gris, Grand Cru Brand

The most convincing pairing of the evening. Dry but expressive, with ripe fruit and smoky mineral notes, it aligned naturally with the grilled lettuce, the cabbage wrapped oyster, and even the pollack. The slight richness of Pinot Gris gave enough volume to withstand the fish reductions without masking the fish itself.

Macallan 25 (Anniversary Edition)

A separate note is necessary here. Céline Couillon, who manages the restaurant, with professionalism and warmth, kindly allowed us to open and taste our own bottle of Macallan 25. This is a thoughtful gesture and not something to be taken for granted in a three star environment. I would like to thank her again for her kind gesture.

The whisky sherry-drive concentration paired will with the darker notes of mignardises and offered a richer, more complex conclusion to the evening.

Conclusion

ConclusionThe visit to La Marine confirmed the confirmed the consistency and maturity of Alexandre Couillon’s cuisine. The technical precision, the restraint in seasoning, and the clarity of flavors are the foundation of his work. The recent renovation and the restaurant management under Céline Couillon give the restaurant an even more coherent identity.

The experience is controlled from start to finish, without unnecessary gestures and without the noise that too often surrounds fine dining.

The menu we tasted showed no weak link. Some dishes stood out for their depts, the homard, the pollack, the rockfish and the others impressed with their simplicity executed at a very high level. The wine menu was aligned with the kitchen, and the openness shown by all La Marine’s team was a gesture of genuine hospitality.

We left La Marine with the clear intention to return next year, and to extend the experience by trying La Table d’Elise, their bistrot next door. Few restaurants manage to create such a sense of confidence and continuity. Couillon’s cuisine is not demonstrative – it is assured, precise and grounded in a true understanding of product and place.

La Marine in Comparative PerspectiveAs far as gastronomic seafood is concerned, there are two kinds of restaurants: Purists and Enhancers (we made up this term, but our intention will be clear soon).

Purists view themselves as “intermediaries” between the ocean and the final dish. Much like natural winemakers, they want minimal intervention, focusing primarily on perfecting cooking time (or lack of it) and method to bring out the maximum sweetness and other inherent qualities of a particular piece of seafood.

Enhancers, on the other hand, seek to imprint their own signature, or style, on seafood and other dishes. Various combinations, contrasting textures, use of spices, etc. are the tools to enhance the flavor of the fish according to the chef’s vision and preferences.

We are not building this dichotomy on the so-called Product versus Sophisticated restaurants because, at the high end, product quality is first and foremost for both the Purists and Enhancers. The purists differ from the Enhancers in philosophy, but their cooking can be very sophisticated. Nobody with a right mind and palate will characterize Etxebarri of the Basque region in Spain as a “simple” restaurant. Perfecting how to cook with fire takes as much skill (but a different sort) as Couillon’s mindful and labor -intensive creations.

In our opinion, considering only Europe and North America, Spain excels in Purist seafood. We have never seen the level of D’Berto, Etxebarri, Bar FM, Los Marinos Jose, Elkano elsewhere. Conversely, we have been disappointed with the Enhancers in Spain.

France, on the other hand, is the kingdom of Enhancers. True, there are excellent Purists restaurants, but they fail in comparison with Spain in terms of variety and exquisity! (Partially thanks to the relative low income, there are more fishermen in Galicia than Brittany who are willing to take risks to fish the rarest species.) The best French Enhancers are amply rewarded by the Michelin guide, and we tried most of them.

In our October trip we tried three of them, on consecutive days. (see the introduction of this article). La Marine is without any doubt at the top of the list. If there is one that can equal it, we have not discovered it yet!

November 14, 2025

France at Its Best: Three Consecutive Years of the Game Menu at Le Gabriel

Since I started dining out in the mid-80s until now, I witnessed the gradual disappearance of the classical French cuisine. Meat and fish cooked on the bone for two and finished at tableside by a skilled server and carefully prepared and long cooked sauces almost disappeared from high end dining. A la carte menus mostly disappeared from gastronomic restaurants. Tasting menus consisting of several dishes replaced them, and the content and style of presentation of multiple course menus gradually became all alike and the search for originality and creativity turned into its opposite, that of sameness and conformity over time. It is now the “plant based” cuisine that is a la mode, and it seems to me that there is a correlation between size, quantity, and impracticality on the one hand, and recognition together with the number of stars on the other. That is, if a restaurant composes a menu with multiple courses and very small portions and presents them in non-traditional vessels (ranging from flower pots, various forms of shellfish, specifically designed strange shaped plates, etc.; which make eating impractical and messy) at least one Michelin star is in their pocket.

This is basically why I frequent Michelin three star restaurants less and less. The experience gets tiring and repetitive after visiting one or two. In this regard I fully agree with David Katz who also published excellent articles here and expressed similar views.

This said, I have been visiting Le Gabriel restaurant located in the hotel La Reserve in Paris for three years in a row in the Fall to taste chef Jerome Banctel’s “Gibier” game meat menu. So after three visits, I can make some generalizations (November 21 2023, November 18 2024, and this time on October 27 2025 along with my friend Julien Mallol). Most importantly, it is an excellent restaurant, combining care and precision in the kitchen with great service and wine selection — the coefficients are a little high but not exorbitant — led by Director Alexandre Augé and the sommelier Gaëtan Lacoste. Secondly, the consistency in both regards is noteworthy as I have not seen any “faux pas” in service or a serious flaw in cuisine in all of the three meals over the years. Finally the chef likes to make some fine adjustments to dishes and substitutes one instead of another. For example, in October we had chevreuil (venison) instead of palombe (wood pigeon). But overall I can see that his style and vision remains unchanged over time. This is truly a chef’s cuisine that I associate with with the greats of the past, including his mentor Bernard Pacaud of L’Ambroisie.

The meal always starts with a trio of amuses: a tartlet with boudin and caviar, a gougere or pommes souffle, and a warm shellfish, such as a clam, oyster, or crab. Julien whose passion for wine needs no introduction, recently tasted the Champagnes of Frédéric Savart. Among them, the Ecueil Trépail cuvée (N.M.) stood out with particular brillance. I found myself enjoying this cuvée even more than the 1er cru “Le mont des Chrétiens 2019”, which I had previously tasted.

Still, I can’t help but I found myself longing for the warm ormeaux (abalone) salad with lentilles, caviar, algue and salicornia. Attesting to the chef’s Breton origins and revealing tremendous complexity and harmony around the marine-sea plants theme, this was a masterpiece.

It is replaced by “game terrine and fine gelee”, with colvert duck, veal, pork, and foie gras with pickled vegetables. The chef also added some pickled wild berries this year which worked extremely well. This is a very good terrine and certainly appropriate as the first course, but honestly it fails to titillate my taste buds (a like terrines with more “gras”, so maybe wild duck is not the best vehicle).

Steamed pheasant hen (poule faisane) with truffled chard, and foie gras is a light dish which is nuanced and aromatic, thanks to Alba truffles, and also texturally complex. Texture-wise it reminds me of something in between a savory parfait and a souffle. It is light, airy and delicious. The quality of the very young and crunchy chard almost steals from the truffle! Unfortunately in this year’s visit the Alba truffles had not become mature and croquant-crisp, and they did not bring the truffle box.

Instead they served the dish with shaved truffles on top. The amount of truffle was certainly less than they served in 2023 and 2024, but, on the other hand, the spongy pheasant hen was even lighter than the earlier versions which used a ravioli from hard durum wheat and added a clear bouillon with the dish. I have a slight preference for the earlier version, but this remains an excellent dish.

2023 version

2023 version

2025 version

2025 versionNext comes the colvert or mallard duck. The wild duck is wrapped in green cabbage with foie gras and is served with two sauces: foie gras cream and duck jus. I normally prefer duck cooked whole and carved tableside, but this duck is outstanding. The chef uses all the parts — leg and breast — judiciously, he seasons well, and he achieves an optimum ratio between duck jus and foie cream. I can attest that that this modern version of a classic dish was nearly perfect in earlier versions, and it is now perfect without any caveats. To accompagny that dish, we chose a German Pinot Noir – Friedrich Becker’s Spätburgunder Kammerberg GG 2010, a wine that still shows remarkable complexity, yet delivers an effortless elegance.

2023 Version

2023 Version

2025 Version

2025 VersionFor those who like game meat, the great partridge is not as prized as “becasse” (woodcock) or “grouse” (Scottish partridge), but it is highly valued. It is not easy to cook game, as the meat tends to be low in fat. So many chefs send to the dining room overly dry meats. I don’t also like too gamey or too chewy versions as I often see in Italy. I believe chef Banctel is a master in faisandage-aging the carcass to optimum marination and seasoning. His “perdreau gris, lait ribot and King Ha Farz” with sauce salmis is a consistently a masterpiece. The lait ribot translation is buttermilk, but the one found in the US has nothing in common with fresh lait ribo. Sauce salmis and buttermilk balance each other, while “king ha farz”– an earthy and crisp powdery dumpling of buckwheat flour enriched by eggs, long simmered meat, raisin and spices — adds a wonderful dimension both in terms of textural contrast and depth in taste. In 2025, they made the partridge dish even more exciting by serving its heart and liver in a brioche on a separate plate.

This year they served chevreuil (venison) loin with exemplary sauce grand veneur and salsify in two forms and textures: fermented and braised like a stick and crisp like angel hair potato fries. The sauce was very good and thick, but my number one slot for the “grand veneur”, which is a sauce poivrade with the addition of cream and sweet jelly, still goes to the Relais de la Poste in Magescq.

On the other hand, one hits the jackpot if they serve “Palombe barbajuan des cuisses, betterave facon “Bortsch”. It is a portion composed of three components. The main part is the rich and optimally gamey breast of wild pigeon which has been roasted under a salt crust and served with an incredibly flavorful sweet (blueberries) and sour (two kinds of beets) sauce with tarragon. The pulled thigh of the pigeon is used to stuff a crisp and fried somoza-like pastry called barbajuan. Finally, in a bowl, they serve the jus of sweetened beetroot and a little cream under which one discovers a “ravioli” of the meat. One eats them all together, and each bite invites one to stop and think and admire its complexity and harmony before continuing to eat.

21 November 2023, all three together

21 November 2023, all three togetherThe feast ends with “lievre de Beauce a la royale, spatzle au sarrasin”. Simply put, if one loves the long cooked hare in a very rich and thick sauce with foie gras, Banctel’s version is one of the very best I have tried. I love this dish and tried many versions. It can be dry or too gamey. But when it is good, it is a very deep dish which to me represents the zenith of gourmandise that I associate with the heyday of French cuisine. Served alongside with buckwheat spatzle, hare jus, and puffed rice, this last savory course makes an imprint in gustatory memory. The Amontillado, a sherry variety, from Bodegas Poniente was a perfect pairing with that dish. I was delighted to see that sherry on the wine list. A small nod to head sommelier Gaëtan Lacoste, who shares the same affection for sherry and has even gone on to create his own label.

The dessert course is always “limestone kiwi, green Chartreuse, shiso and sabayon”. This is a nice and modern dessert which is very appealing and appropriate after the journey into game territory.

November 7, 2025

Steirereck am Pogusch: An Excellent Austrian Country Inn

We enjoyed too many places in the recent trip through Austria to review them all. But if I am asked which I’d be most eager to return to, one stands at the top of the list: the country inn Steirereck am Pogusch. We spent two nights there and it wasn’t nearly enough.

I’ll get around to discussing the food but, let me first describe the environment the Reitbauer family has created there. The heart of the property is the Wirtshaus.

In the English language, there are inns and innkeepers. In German, Wirt means not the building but its host. So Wirtshaus means the host’s house. Emphasis is given to the person, not the structure. This is abundantly apparent throughout the entire Pogusch property. Every detail reflects the taste of this family, refined yet lighthearted.

The Austrian country charm of the original building has been lovingly maintained, but when they wanted more space, they attached a modern wing that makes the statement, we appreciate equally the architecture of the 21st century and the homey comfort of the 19th.

We were lucky to find a room here. It had been booked solid for several months before we wanted to come. When we had lunch in the family’s Vienna city restaurant, Steirereck am Stadtpark, I mentioned to our server that we were sad not to be able to visit their country place. “Let me see what I can do,” she replied. A few minutes later, she came back to report that she had managed to get us a room. I happily put it down in my calendar. More about that “room” later…

You enter the Wirtshaus through this inviting entryway:

The happy coexistence of old and new continues throughout the dining rooms:

The property is first and foremost a farm. In addition to the cows, sheep, goats, pigs and chickens, they raise over 500 varieties of fruits, vegetables and herbs. This produce becomes the heart of the menu both here at Pogusch and at their more formal restaurant in Vienna. “Farm to table” and “sustainable” have become clichés, but here both are entirely genuine.

Throughout the property are clusters of dwelling units, each with a unique personality. They all manage to be homey, quirky, and elegant, displaying the family’s distinctive taste.

We stayed in one of the four Vogelhäuser (bird houses). Each is named for a kind of bird. Ours was called Kuckuck, or cuckoo. I have to describe a few of its features to give you a glimpse of what makes the whole place so special. The bird houses sit on a hill with a view that stretches for miles across the green Styrian countryside. Entering the birdhouse hill, you’re greeted by this sign:

Only for Nesthocker. What are Nesthockers? It’s a play on words, meaning nest-sitters. It means baby birds that stay for a long time in the nest and also means stay-at-home people. Any people lucky enough to stay in these bird houses are going to want to stay there as long as they can.

Wrap-around decks look out over endless hay meadows cut into the forested mountainsides.

When you enter the front door, a quiet recording of bird and insect songs plays. After a moment, you hear the call of a cuckoo. Inside, the juxtaposition of old and new continues, exemplified by this stainless steel woodburning stove.

The bathroom includes a sauna and both indoor and outdoor showers.

On a wall of the toilet enclosure is this depiction of nursery rhymes about cuckoos. The cuckoo theme extends even to bath towels embossed with a cuckoo.

The bird houses are just one group of accommodations. Each group is unique. The Baumhäuser, or tree houses are clustered in a wooded grove.

In the Glasshaus, guests have suites within the farm’s greenhouses.

One of the old barns has been converted to guest rooms, called Schlaffen im Stall (sleep in the stable.)

Within the woods and among the farm buildings are the Jagdhütte, Rehleinhütte and other guest accommodations, each utterly charming, and each possessing understated luxury.

Two of the Reitbauer’s young adult children were managing the dining room during our stay. They clearly regarded their time there as not merely a job, but something more akin to a party that they loved hosting. I told the son how much we were enjoying the Kuckuck house. “Well, you can thank my grandparents for that. Every stick of it was theirs.” He shared an honest openness about how he saw his future. “My parents told me I could do anything I want, be a doctor or anything I liked. But I love it right here. In this business, your work is your life. You’re giving your guests not just food but an experience that you hope will touch them deeply. In what other job could I do that?”

I turned out to be one of the guests who was touched deeply. During my time at Pogusch, I thought a lot about why I care about restaurant meals. The young Reitbauer’s statement about sharing not just food but meaningful experiences captured what makes me spend ridiculous amounts of time and money roaming around looking for places to eat. The food has to be good, of course. But there’s much more to it. My favorite chefs are trying to share something that transcends the food: fond childhood memories, cultural traditions they fear may vanish, or surprising sensory nuances. There’s an intimacy in this process that moves me.

The Reitbauers have come upon a formula that combines features of traditional a la carte dining with the modern multicourse menu. They serve breakfast, lunch and dinner seven days a week. Most of the guests are here for a stay of several days, and the Wirt needs to provide them different experiences each meal. Here’s how they do it.

The main dining room serves completely different a la carte offerings each day, Wednesday to Saturday.

Wednesday’s menu is titled “Garden—field—woods.” It’s not entirely plant-based, but it gives vegetables first place. Here’s an excerpt from Wednesday’s menu:

Vegetables are incredibly diverse. They smell and taste green or fruity,

from sweet to sour, from bitter to savory.

They can be crunchy or velvety, juicy or creamy,

they can be cooling, stinging, or sweetly indulgent.

Vegetables are a delight for all the senses.

Grilled leek hearts with salted carrots, pickled mushrooms,

crispy linseed & herb salad.Baby Carrots

Glazed carrot variety with marinated herbs from our kitchen garden.Fennel

Braised with Pogusch citrus, Pernod & coriander seeds & fennel greens.Eggplant

Braised & spicy glazed eggplant with brook cress & Meyer lemon.Sweet Potatoes

Oven-baked in their skins with spicy paprika-chupetinho chutney.Chickpeas

Baked chickpea pastry with mountain cheese.Vegetable Salad & Buddha’s Hand

Marinated & pickled vegetable variety with Pogusch Buddha’s Hand citrus.

All sorts of things from Styrian gardens

Then, as on each of the four days of menus, there are two other pages of choices, one called Authentic, Trusted, and the other Refined, Simple. They list traditional Styrian specialties updated with the kitchen’s unique insights, and the chef’s selected preparations of lamb, veal, chicken and pork from the farm and fish from nearby mountain lakes.

Not to overwhelm you with the rest of the menus, I’ll just say that Thursday features “Inner Values,” snout to tail items from their lamb, pork and veal, Friday is “Freshwater fish day,” with whatever was just caught in the nearby lakes and streams, and Saturday is devoted to Styrian veal.

On Sunday, Monday and Tuesday, lunch and dinner are set four-course menus based on the best the farm has provided those days.

Here was our dinner on Monday:

As an amuse bouche, they brought this board of Pogusch pork, pointed peppers and horseradish, each of which they grew.

Each of the four courses was simple and perfect. Vegetables in Aspic contained rungia klossi, a green with a pronounced mushroom flavor. We could see from our walks in the nearby woods that mushrooms were nearing the end of their season. No doubt that was why the mushrooms in the dish were marinated rather than fresh.

The kitchen makes great use of the tremendous variety of mushrooms that grow in their property and the surrounding forest. Have a look at this display in the breakfast room, each jar containing a different species of locally foraged mushroom. The letters spell out “a remembrance of the diversity”

Styrian sour cream soup with marinated and smoked salmon was a delight.

Pogusch pork was from one of their own pigs, accompanied by kohlrabi, green beans and braised romaine, each of which they grew. The terrific sauce was flavored with herbs they also grew.

Nasturtiums, both as flowers and leaves, were a nice piquant accompaniment to the perfectly roasted potatoes.

The Steirereck Pogusch team cultivates dozens of varieties of potatoes, looking for the best for each method of cooking. I don’t know which one they chose for roasting in this dish, but they were delicious.

This potato plot was just beside the drive leading to our bird house. Each sign marks a row of a different variety of potato.

Poppy seeds and cheese curds inside a delicate beignet accompanied marinated and braised apricots from their orchard, vanilla ice cream and lemon verbena. I could eat this dessert every day and never grow tired of it. Come to think of it, I wish I had it right now.

Espresso came with candied citrus rind and sugared roasted pumpkin seeds. These seeds are an indispensable ingredient in Styrian cooking. They can flavor eggs at breakfast, mignardise like this one, and everything in between.

Tuesday’s dinner was entirely different and no less enjoyable.

I neglected to photograph the first dish, kohlrabi, veal tartar with wild herbs.

The rustic potato vegetable soup was everything you could hope such a dish would be: warming, comforting, rich and flavorful. Grandma would have highly approved.

Schneebergland duck came with cabbage, celeriac polenta and lettuce. Schneeberg is a nearby small mountain. The duck combined all the qualities one hopes to experience in duck but most often doesn’t: crispy skin, tender meat, satisfying duck flavor. The rich sauce was excellent with both the duck and the tasty celriac polenta. The lettuce doesn’t look like much, but it was outstanding.

Before I remembered to photograph it, we gobbled up half of the tasty peach and semolina kaiserschmarrn, the classic Austrian countryside dessert, named for Emperor Franz Joseph I who supposedly loved it.

There’s also the option of eating at the bar in the kitchen. There you can order from an ever-changing a la carte menu, or else opt to “let it flow,” meaning trusting the chefs to give you a succession of courses of their choosing. Here’s how they describe the kitchen bar:

The most fun is always to be had at the bar! This is true of our Schankkuchl too. At the heart of the action you sit at the long bar in a cozy and convivial atmosphere with your fellow guests and observe as the chefs prepare your dishes over the open fire or steam them in front of you. In the show kitchen the bounty of our farm and the region receives a contemporary and delicate interpretation.

We didn’t get to experience the kitchen bar but would love to when we return. Here are some tempting excerpts from the bar menu. The coexistence of old and new is in full force here:

Devil’s roll winter editionSourdough, stracciatella, wild broccoli, bacon, mushroom, kimchi.Kissed by fire

Pogusch lamb, viennese garnish, pogusch heurige.Bear strong

Bear & fruits, sorrel, salted caramel.Loafing around

Liwanzen (yeast pancakes), wild fruits, apple plum, soured creamThe best of both worlds

Sour vegetable salad, short rib, coriander, mustard.Bikini figure snack board

Autumn vegetables, sheep’s milk cheese, barberry, nettle.Chick stickx

Hen, romanesco, mountain pine cones, curry leaf, lemon balmKing or beggar

Carp, pumpkin, sea buckthorn, spinach, basil.Overflyer

Young pogusch chicken, roasted onions, chanterelle mushrooms, meyer lemon.Valhalla

Catfish, kohlrabi, horseradish, variety of beets, vanilla.Pearls before swine

Jerusalem artichoke, quinoa, farmers’ caviar, chives.

LET IT FLOW__________________________________ min–max _110-155

The open fire bar kitchen

The open fire bar kitchenWe came to Pogusch in search of alternatives to the tasting menu format that Michelin seems to consider the only thing worthy of multiple stars. I was feeling tired of dozens of tiny complicated dishes, each with a sip of a different wine. I was tired of those pock-marked white plates with the tiny depression in the center for two bites of food. I had no more patience for kitchens whose most commonly used implement is the tweezers.

Michelin reviewers, if you’re reading this, ask yourself: how soon and how often would you like to return for dinner to any particular one of your three-star places? For me, the answer in almost all cases would be not for at least a month and maybe two or three times a year. After you enjoyed a dinner in such a place, would you like to come back the next day? For me, the answer would almost always be no.

For Steirereck Pogusch, in contrast, my answer would be that I’d like to come back not only the next day but every day for the next week. Isn’t that worth some stars?

As Robert Brown so cogently pointed out in his article Form Swallows Function, the tasting menu is to the advantage of the restaurant and the detriment of its guests. It allows the kitchen to crank out the appearance of variety with assembly-line monotony. It allows them to reduce waste by knowing that every customer is going to eat the same thing. Almost every restaurant that has or aspires to Michelin stars has fallen into line with this format.

At Pogusch, the Reitbauers have evolved an excellent alternative that I hope will inspire others to emulate it. The pendulum of gastronomic fashion has swung as far as it can toward tasting menus. I’d like to propose Steirereck am Pogusch as a model of what it can swing back to: a dining experience that combines best features of the past and the present. I’m eagerly looking forward to another visit there and hope it will be soon.

October 30, 2025

Disfrutar Barcelona: The Amaranth Coral and the Spirit of Avant-Garde Cuisine

In mid-July 2025 we visited Disfrutar in Barcelona. Ranked as number one in the world by 50 Best and with Michelin three stars, this is a highly regarded restaurant. The cook/owners and some of the staff spent years at El Bulli, and as you would expect, there are important continuities in terms of overall vision, menu design, and cooking techniques. Playful, irreverent, a little theatrical and at times amusing, Disfrutar is certainly a must to visit for those interested in the history and the current state of avant-garde gastronomy. But unlike the Scandinavian school with its predilection for conveying puritanical and moral messages to the client and the patronizing attitude accompanying that “mission”, Disfrutar, like El Bulli and Enigma, encourages reflection and reciprocity. That is, the attitude of the staff and menu design encourages dialogue between the kitchen and the client, joking and having a good time, while feasting on some exquisite dishes. Although I have not spoken with any of the three owners, I sensed that they are not too pretentious and do not take themselves too seriously. Rather they seem to want people in their restaurant to have a wonderful “sobremesa” by spending four hours relaxing, conversing, laughing and enjoying each other’s company.

However the food is very serious, clearly rehearsed many times and perfected. It is well thought out in terms of portion size, the sequence of dishes, and overall balance. Fortunately, unlike many “top 50” or Michelin three star restaurants, dishes are actually delicious and not merely conceptually intriquing. We also appreciated the fact that when we left we felt satisfied but not uncomfortable due to over-eating and indigestion. Consequently we slept well.

Four months have passed after our visit to Disfrutar. When we look behind and evaluate the meal, what stricks me and my wife the most is not the existence of some brillant dishes. Such unforgettable “anthological” dishes are rare, but I have seen them at Alain Chapel, Jamin-Robuchon, Freddy Girardet-Hotel de Ville, Bernard Pacaud-L’Ambroisie, and Fernan Adria-El Bulli. Rather it is the overall harmony, consistency, and the flow at Disfrutar that impressed us.

Once ushered to your table, a kind of palate cleanser is served: frozen pina colada, that is the molecular version with pineapple in contrasting textures and temperatures. Then one toasts with “forest floor”, a low alcohol distillate from water, dried herbs, and moss. Obviously this aperitive is a vehicle to toast (serving this in a copper cup was a neat idea), but its true intention is to alert the plate for the first taste experiment. That is, an oval plate is served containing eleven sprouts. One is supposed to discover flavors after smelling and tasting the sprouts one at a time. For instance persinette is parsley. Scarlet is beet. Borage is cucumber.

I liked this challenging game, not only because it is a tribute to mostly forgotten earthy-natural aromas and flavors, but the intended discovery of the hidden world of green sprouts sharpens and broadens the palate. It is a proper beginning to a long meal containing a multitude of flavors.

What kind of dishes or aromas-flavor combinations should follow the “sprouts” test game?

Well, it is followed by “polvoron” and liquid salad, both served in a metal ice cream container, like a glass. Honestly I have never eaten Polvoron which google describes as “a type of heavy, soft very crumbly Spanish shortbread made of milk, sugar, flour and nuts.” This version is powdery, but not sweet. It contains tomato and arbequina olive oil. Neither this and nor the pink liquid salad made an impression on me. Perhaps they were intended as harmless amuses to keep the taste buds fresh before the onset of savory dishes.

While we were trying to figure out the secrets of the “liquid salad”, they serve truffle scented vodka in a cognac glass.

Truffled vodka raised our expectations, and we were not disappointed. The next three dishes all featured fresh oscietra caviar from China. The first dish was a fluffy, weightless fried bun filled with caviar. It is basically made from unfermented dough, and the idea is to show the temperature contrast between the exterior and interior of the fritter. It tastes very good, and since the technique is to fry a siphoned foam, the so-called “Chinese bread” is very light and non-oily for a fritter.

The middle course was reminiscent of crisp bruschetta topped by a generous dollop of caviar and solidified bubbles of smoked butter. (They must be using a technique similar to previous dish.) The bruschetta or thin waffle was inky black, and it is like a crisp version of the well known mole sauce. At any rate, this dish is delicious. The rich creamy-sweetness of oscietra caviar was exponentially augmented by condensed butter, but it was also tempered by the piquant mole. Both paired well with the truffled vodka.

The last of the trio featuring caviar was the most complex and profound: amaranth coral with caviar, oyster, and codium emulsion. The coral tart is made from amaranth grain and is topped with sturgeon (oscietra), as well as trout eggs, oysters, and codium (seaweed). These flavors highlighted the saline-iodized component of the caviar, but the overall harmony and depth of the dish rendered it perfect. This is one of the best caviar dishes, on par with Thomas Keller’s “oysters and pearls”. The anatomy and history of this dish is explained with painstaking detail and precision by gastronomy expert Carola Sitges who is also a good client of Disfrutar. I URGE ONE TO READ IT CAREFULLY HERE as it will provide an in depth understanding of Disfrutar’s philosophy.

I should add that the presentation of this “Amaranth coral” is accompanied by a little ceremony or optical illusion, a la Disfrutar. I have mixed feelings about its relevance, but it can be better understood by reading Carola’s article.

When we were reveling in the intense and deep maritime aroma and flavors, the next course was presented: a kind of “gazpacho with pistachios, green olives, various oils.” I could not quite concentrate on it, but noticed that they used an Adria style spherification method to the fullest. I recall fresh, bright, and balanced summer flavors. It was well conceived, following three consecutive rich courses.

But it is impossible not to remember the next taste explosion: flourless ‘coca’ bread with “escalivada” and anchovy. At home and in summer-fall, I love to eat grilled sourdough bread with caramelized red pepper, onions, eggplant, and Cantabrian anchovy. The often used cliché, “umami”, may be appropriate here as the overall taste combination is very rich and savory. Here they both lightened the Catalan traditional escalivada (smoky grilled vegetables brightened by sherry vinegar) and they concentrated the umami impression. The traditional coca flatbread was very light but crisp. When I asked, they said that they made the dough from potato starch-pliant kokko oblate to make it light. Yet its topping was true gourmandise.

After this very strong taste, what should come next? Well, they followed this with a display of an overly technical dish: crunchy mushroom leaf served alongside crispy egg yolk with warm mushroom gelatin and a fried egg ball sitting on egg shell with mushroom consomme. These visually beautiful two dishes did not make a strong palate impression. The latter showcased an interesting technique where the egg yolk was fried very fast (they said it was microwaved) and looked like a fried Chinese bun.

Next two dishes made a good impression. Oyster escabeche was served with four different kinds of fermented mushrooms, toasted pinenuts, and ice plant. This was an excellent example of mar y muntanya style dish which are very popular in Catalan cuisine. The sake they served paired very well with the fermented umami component of this dish.

The smoked eel, pesto (in spherical form), pine nuts, pistachio nuts, and pancetta combination was delicious. The parmesan cream sauce brought together the different components of this course.

Then it was the turn of my favorite Catalan green calcots (a sort of wild green onion). The season is very short, mid-April to mid-May. Normally they grill it and serve it on paper with sauce romesco. Since they served calcots in mid-July, they were freeze dried. They used the stem of the calcots to make a dashi. This was presented in a cognac glass. They also made a version of romesco sauce with miso. The result was quite good but by no means is a substitute for freshly grilled calcots which we have had on several occassions. (Somehow our server did not seem to believe that we knew what calcots were!).

I am not a fan of suquet fish stew as the fish tends to get overcooked, but the hake suquet was excellent. The hake was fresh and most likely it was not cooked in a stew. The fish stew was presented in a separate coffee cup and called “cappuccino of suguet”. On the plate, potato foam, potato gnocchi, and saffron aioli accompanied the fish nicely. I noted the quality of the saffron as another positive point.

The most perplexing dish was the next: “the hen of the golden eggs: crustacean fried egg”. They first leave on the table a deep plate simulating a nest, with a straw and five eggs with a barcode and a sixth egg painted gold in the center of the nest. Then they serve the dish that we are going to eat and recommend breaking the golden yolk and combining all the ingredients. The egg white is very well fried and a langostinos prawn tail is cut into three pieces and placed on top of the heavily toasted tips of the egg whites. According to Carola, whom I asked to explain this dish, the golden egg yolk was a spherification of a red sauce that looked like srirasha and was golden on the outside. Overall the dish looked like “fried egg white shrimp tortilla”. In personal correspondance Carola writes: “It is a deconstructed fried egg something in between a tortilla de camarones and some traditional Thai recipe, perhaps a kind of deconstructed Pad Thai.”

The final savory course was excellent: squab. When I asked its provenance, they said it was semi-hunted and came from Madrid. I did not quite grasp what they meant by “semi-hunted”, but it was a great squab, tender but also with a gamey edge that made the meat more flavorfull. (Most likely the squab was strangled.) They served it with two sauces: liquid manchego (fonduta texture) and a demi-glazed flavored by beet juice. These two were separated by bow shaped spaghetti made from agar agar. (See the photo.) A beet merinque on the plate was a nice extra touch. The excellent 1952 Rioja Gran Reserva they served by glass elevated the experience to a higher plane. My only wish is that they should also present the liver, internal organs, and the thigh of the pigeon alongside the breast as these are often the most flavorful parts.

Like almost all Michelin three star restaurants with degustation menus, there are too many desserts. I think it would be more satisfactory to offer a cheese course and only one dessert, but I know that inexperienced diners seldom frequent these type of restaurants and when they go they only remember desserts. I rarely remember a dessert unless it is exceptional. Disfrutar served one exceptional dessert: cucumber sorbet, black sesame, ginger granita, hoisin sauce, and chicharron (deep fried porc rind). This was not solely original and well conceived but also delicious. It was multi-dimensional and at the same time complemantary and contrasting elements hung well together.

We also loved the final gesture. They present engagement rings in a jewelry box. There are a total of 25 rings and one selects as many as one intends to get get engaged in the course of life

One doesn’t also leave Disfrutar thirsty. As I have written above, they offer a ‘forest floor’ coctail, truffle infused vodka, and sake. Besides the glass of old Rioja Gran Reserva, we ordered an excellent champagne, Dehours, Les Genevraux. Made from pinot meunier with the Solera method, this is a deep and fresh tasting champagne. The white wine, a non-fortified Palomino, 2022 M. Ant De La Riva Macharnudo is an excellent wine from Jerez that I had three times. I was equally impressed each time.

I left the restaurant happy that I got engaged only once and married the right woman. Nonethless I should have eaten more than one engagement ring!

EVALUATION: 9/10

Part II – The Amaranth Coral: In Depth Analysis by Carola Sitjas i BoschI’m often told that my write ups are so long that, if I published only what I say about a single dish, it would already be an article that within a single chronicle there are several articles and that I write books rather than restaurant pieces.

What’s more, I complain that press releases don’t go deep; when they explain the latest menu at, for example, Mugaritz; a restaurant that invites you to write, think, and rethink. They simply transcribe the names of the dishes as they appear on the reminder card and pad them with generic adjectives like “a must try,” “the iconic,” “the delicious”; connectors like “followed by,” “next,” and “to finish”; and they transcribe quotes from the chef without offering any opinion beyond a bit of praise. In other words, a flat EEG.

When I posted photos of the latest menu I ate at Disfrutar this past Tuesday, October 7, 2025, I was surprised by how many people told me their favorite dish was the “Amaranth Coral.”

One of the dishes considered iconic at Disfrutar is the “Chinese bread stuffed with caviar and sour cream” from 2016, and I had no idea there was such (probably skewed) unanimity around the coral. Personally, I like the “Chinese bread,” but it’s not one of the dishes I’d highlight at the restaurant. Technically yes, because the idea of frying a siphoned foam alone thrills me, and I think the unfermented dough is very well achieved; but in terms of flavor, even though I value the two temperatures (the interior and exterior of the “fritter”), a taste of frying predominates that I associate with cuisines far less aesthetic, sensitive, refined, and intellectual. That’s why I liked seeing a different dish so clearly singled out.

I’ve said many times that Disfrutar is one of those restaurants I could talk about for hours and hours; I think their cuisine allows for that and much more.

I often read and hear the comment “not much left to say,” not only from enthusiasts but also from chefs and journalists. It seems to me you can talk about restaurants by going a little further than assessing product quality, doneness, and whether the dishes suited our personal tastes.

For all these reasons I’ve decided to publish just some thoughts on Disfrutar’s “Amaranth Coral.”

If I hadn’t previously published an article exclusively about one dish, it’s because, in a way, isolating one and discussing it without the broader context of the menu, the restaurant, and its trajectory can lead to misinterpretations and seems risky to me, since we’re talking about only two or three bites from a menu that, in this case at Disfrutar, consisted of 32 items (26 plus 6 petits fours), just as some journalists decontextualize a quote from an interview to craft a click bait, tendentious headline.

EXPLANATION OF THE DISHOn the one hand, the base is a crunchy amaranth that’s somewhat similar to a “cookie” of puffed rice.

First, they “soufflé” the amaranth. Technically, I understand that to “inflate” and to “soufflé” are the same and achieved similarly to how potatoes are made into pommes soufflées, how rice is puffed, or how corn pops to make popcorn that is, it bursts thanks to the moisture in the endosperm, where the starch is. That said, even if the terms inflate and soufflé are used interchangeably, I’d say they’re different processes and, physically speaking, inflating is different from bursting. Perhaps English makes this clearer, since “puffed rice” (which preserves the grain’s shape but is much larger) is different from “popped rice” (which has an irregular shape like popcorn).

Then they grind the souffléed amaranth, mix it with a green and a red coloring, add vodka, and fry this mass. Because it contains vodka (alcohol), when it comes into contact with the oil, the vodka evaporates very quickly and expands what’s inside (the mass), thus achieving the coral shape. I understand they add vodka to create more internal moisture. Technically, I don’t fully understand why they add an alcohol (wouldn’t water work?), and I imagine they use vodka rather than gin, white rum, or another clear spirit to contribute as little aroma as possible.

On the other hand, on top of this crisp and much easier to grasp go salmon roe (we’ve also been told trout roe at times), beluga caviar, a codium mayonnaise and pieces of codium, and finally two pieces of oyster. Even so, whether due to the season or because it was the first version, back in January 2023 they served it with sea urchins and the two codium textures, but without caviar, oysters, or salmon/trout roe.

The presentation of this dish also comes with a whole little ceremony and explanation. It’s served inside a black box with a pane of glass standing vertically in the middle. They ask us to take the coral, but we can’t find it. Then they remove the glass pane from the box and we “discover” the coral. The idea is to create an optical effect that confuses the diner, to prompt reflection on the plate (the tableware), on whether we’re supposed to eat the decoration and accompaniments or not, whether it’s necessary to have the decoration on the plate or simply to see it, and on garnishes and ways of serving food an idea very much in the elBulli vein that they’ve been developing for years. It really is a magic trick!

A dish that carries a message, a reflection but I understand it’s a game that could be adapted to other aperitifs, like Parmesan crisps, for example and that there’s no inherent connection between the optical effect and the coral.

ASSESSMENT OF THE DISH – Organoleptic analysisAppearance: It’s very beautiful, delicate, and fragile, very Disfrutar and the mirror effect achieved with the black box makes it shine even more.

Aroma: Scent is not what I’d highlight in this dish; amaranth isn’t exactly an intense ingredient. But of course, the seafood is at the right temperature and gives off some aroma.

On the palate.

Temperature: It’s very pleasant to feel the faux “toast” contrasted with the freshness of the seafood.

Texture: I really like the unctuousness/moistness that the codium emulsion lends to the crisp, without sogging it, yet giving it “juiciness,” and the crisp itself is “soft” in the sense that it’s easy to chew. That is, you have the fragility of the crisp and the density of the seafood, perfectly combined.

Taste: I remember that the first time I found the crispy component a bit disproportionate to the sea urchin and would have liked to taste more sea urchin and less “fried bread,” but as they serve it now (with oyster, salmon roe, and caviar, together with the codium emulsion and whole codium) the “coral” is more generously filled with seafood, and the bite conveys more marine freshness and that intense, deep maritime “punch.”

Even so, and this is a bit contradictory, i really liked the version with sea urchins. They source sea urchins of a caliber that’s a joy to behold, served impeccably clean, whole, without a flaw… they’re so good and I eat them so rarely that, frankly, I might have added a couple more.

I won’t give any auditory assessment, because beyond the pleasant sound of anything crunchy, there’s no need to act like such “snobs” (to put it politely).

ASSESSMENT OF THE DISH – Evolutionary and stylistic analysisIf I’m not mistaken, I’d say it’s a 2023 dish. At least, the first time I ate it was January 2023.

Over these nearly three years, I’ve eaten it three times, and in that period it’s been versioned based on products available in different seasons of the year. It has also moved around in the menu, going from dish number 14 to number 5, something they often do and which I find very sensible, whether for taste and service reasons, or because when they introduce a new technique they tend to present it alone, as bare as possible to give it full protagonism and on future visits it appears within a dish as a garnish or as one element among others, or, as with the coral, relegated to an aperitif and “de emphasized,” since they are constantly introducing novelties.

On the reminder cards, the dish appears as “Amaranth coral with sea urchin” (2023) and as “Amaranth coral with caviar, oyster, and codium emulsion” (2024 and 2025).

I also think it’s worth noting that, although at Disfrutar they don’t break the reminder card into “snacks,” “starters,” “first course,” “second course,” and “desserts”, a breakdown that became obsolete decades ago at many high end restaurants with long, narrow menus, we’re talking about a dish that would be the equivalent of an hors d’oeuvre (I’ve always eaten it at the start of the meal, between dish 14 and 5) and not a main course. And for some reason, it seems people don’t demand the same level of rigor from an aperitif or a petit four as from the central courses of the menu.

It’s a tartlet/canapé format so typical of the “fine dining” circuit of “gourmets voyageurs” who follow rankings and lists Jordnær, Sézanne, Hiša Franko, Coda, Mirazur, Trèsind, Victor’s Fine Dining at Christian Bau, etc.

But I’ll stress again that, in Disfrutar’s case, it’s an aperitif and not a course; therefore I don’t find the format at all objectionable. That said, as an aside, one of the things I liked about this last visit was that the second aperitif “Centrifuged macadamia fat with milk skin, caviar, and mango” was in plate format and meant to be eaten with cutlery (in this case, with two spoons, which I love, as spoons are the great forgotten tool).

Technically, physically, and chemically, I find it magical, just as I find it magical that a corn kernel turns into popcorn, even if cereals had already been puffed before.

Stylistically, it doesn’t seem among the most representative of Disfrutar, as it brings together two creative lines followed by quite a few other chefs who work precisely at this junction of “elBulli style + seafood cuisine”: Aponiente, Quique Dacosta, Miramar, La Madonnina del Pescatore, Uliassi, Mirazur, Gérald Passedat’s Le Petit Nice, etc. I even think it could be a dish from Dos Palillos or other Japanese influenced restaurants inspired by elBulli, understood as a kind of crunchy “sunomono.” In fact, if I ate it blind in 2025, I might not say it was from Disfrutar, even if in 2023 puffing amaranth was a novelty. That said, if we look closely at how these other restaurants carry out the fusion of elBulli style with seafood cuisine, we see that Disfrutar is the only one developing techniques substantial enough to be considered new.

As for the product, I’d say the dish doesn’t introduce any new ingredients for them: codium seaweed, oysters, sea urchins, caviar, and salmon roe were all worked with at elBulli; perhaps amaranth is the “newest,” appearing as a novelty in elBulli’s 2005 menu, twenty years ago now.

Also regarding the product, the sea urchin version allows you to enjoy them in their entirety and doesn’t require chopping them as in the oyster version, where you lose the sense of fullness and the meaty quality of oysters eaten whole. As always, there are examples that could sway us for or against cutting, mincing, or heavily manipulating an oyster, but I still remember what felt like sacrilege conceptually when, perhaps twenty years ago now, Nandu Jubany made an oyster tartare.

As for the product once more, perhaps the only point to criticize is the coloring, since to the uninitiated it sounds like a “bad” ingredient. I’m sure there are quality colorings and many natural colorants (like the seaweeds themselves) and many ways to “dye” food, but it brings to mind those dyes used to tint jeans and used in some countries outside the EU to color that aberration of “wasabi” in a tube that looks like toothpaste. Maybe I’d avoid presenting the dish by saying the word “coloring,” so as not to trigger the pro natural zealots afraid of being poisoned by the infinitesimal dose of sulfites in a bottle of wine, for example, and I’d explain that they achieve the green with seaweed, or whatever it is they use to tint it.

AMARANTHA parenthesis to talk about amaranth, since it’s a food that’s fairly foreign to me and that I associate with an Aztec origin from Mesoamerica.

It’s an ingredient I’ve practically never cooked with, except for a few bags from the Catalan company Biográ that I bought about four years ago, with dried amaranth seeds from India that I simply cooked to get to know the taste and ended up using only in salads and other dishes as if it were a legume. It took some effort to finish the bag and, in the end, I had to fry part of it and put the rest in the oven to use like sesame, seeds, or croutons as a crunchy element in some dishes.

I find it an inexpensive ingredient (I was buying it at €4.50/kg raw), and I associate it with South American countries, where I imagine it grows in poor soils and is consumed regularly to avoid malnutrition.

When I bought it for Ca La Carola, I took a bit more interest in the product and discovered that, botanically speaking, it’s considered a pseudo cereal that is, it doesn’t belong to the grass/poaceae family (where cereals are), but rather to the amaranth family, like quinoa, chard, spinach, and beet. Even so, due to its high starch content, in the kitchen it’s used like a cereal and has the “virtue” of not containing gluten.

My references for amaranth are scarce. I tried to jog my memory and look through my archive of reminder cards and found that in April 2005 I had it at elBulli in the dish “Sole with souffléed amaranth and amaranth air with coriander.” I’d say it’s dish 1176 | sole with puffed amaranth, Córdoba air, coriander amaranth/popcorn, Chinese chive blossom, and lemon.

That same 2005, elBulli also did “Little snails in court bouillon with pickled velvet crab and fennel amaranth” (dish 1170).

Another restaurant where I remembered eating amaranth was Mugaritz, and I found that in December 2009 I ate sea cucumbers sprinkled with amaranth seeds like crunchy crumbs. From the same restaurant, I also have a vague memory of a fish dish with “acidic amaranth sprouts” and a salsify nixtamalized or “fossilized” with the lime technique, accompanied by amaranth crumbs mixed with some fish roe so that they were visually confusable, since both were granular. And in 2025 Andoni is doing the dish “amaranth seeds with chile miso,” which I haven’t eaten, but it truly looks like a micro plantation of sprouts. I also found that in 2006, for Mas Pau’s 30th anniversary, Andoni cooked “A modo de una pasta, amaranto guisado con un caldo de sardinas guarnecido con colas de cigala y hojas tiernas del huerto como una bleda vermella” and a recipe of his based on scallops and tubers “roasted” covered with amaranth, slices of sweet acorn, and winter purslane, dressed with clay and truffle.

On 08/31/2020, Andreu Genestra (Mallorca) served “Potato, olive, oyster, and cockles.” A very typical Andreu dish, since it was three dishes in one, or in which he plated the accompaniments on separate plates.

On one plate there was a potato parmentier with an oyster on top and a green olive gel.

On a separate plate he served an almond “crêpe” with a stew of pochas (white beans) inside, potato sauce, and amaranth.

On a third plate, a crisp cookie made of potato with a base of fresh herbs, finished with three dots of black licorice and three cockles on top.

In Italy in recent years I’ve had it at AlpiNN (Bruneck/Brunico) with Norbert Niederkofler, where on 09/22/2021 he served the aperitif “Cabbage with puffed amaranth”; at Lido 84 (Gardone Riviera) with Riccardo Camanini, where on 03/31/2023 he served “Amaranth crisp, smoked eel cream, and black kale powder”; and at Clandestino (Portonovo) with Moreno Cedroni, where on 08/19/2023 he served “Ricciola con porro e lemongrass, viola del pensiero, basilico amaranto,” a 2010 dish raw greater amberjack accompanied by a leek and lemongrass sauce and, on top, fried amaranth (as crumbs), basil, and pansies. Very thin slices of a very tasty amberjack with a delicate dressing.

In short, amaranth strikes me as an uncommon ingredient in haute cuisine, with lots of possibilities even as a flour for bread and other doughs, or as a beverage, making a kind of “amaranth milk,” as is done with rice and other grains.

Closing the amaranth parenthesis: simply by racking my brain about where I’d eaten it, I was surprised to find more examples than I’d have thought at first. But in any case, I find it curious that all the dishes combine amaranth with products from the sea fish, crustaceans, fish roe, or seaweeds except for Andreu Genestra, who used it in a sauce with potato that accompanied an almond crêpe stuffed with a bean stew (legumes).

THE CORALLastly, to close the evolutionary and stylistic analysis of Disfrutar’s “Amaranth Coral,” I think that, in terms of embodying an idea based on a non culinary element, the dish is very well achieved.

Even though we also call the red part of scallops, zamburiñas, lobsters, and brown crabs “coral,” we all understand that Disfrutar’s coral refers to the marine invertebrate which, though some consider it a plant and others an animal, I’d say is not eaten besides being highly protected and considered a prized object. This double meaning could also serve as a wordplay to stuff the amaranth coral with lobster coral, for example making a “coral of coral.”

I think of chefs who have tried to “cook” marine coral and, right now, the only thing that comes to mind is elBulli’s 2005 “morphing,” the “chocolate coral” (dish 1212), but that wasn’t a dish that intended to transmit the taste of the sea; it was simply a chocolate in the skeletal, branched shape of a reddish coral.

It’s a dish that can call to mind, aesthetically and in its marine profile, Disfrutar’s “aerated sea rock” from 2024 (dish no. 10 on the October 2024 menu).

It was a “rock” they made from a béarnaise with some mussels; they put this sauce in a siphon to make a foam and vacuum sealed it, so that all the air in the foam expanded, achieving a very light, delicate texture. Then they put it in the blast chiller to cool it very quickly and so it would retain the spongy form.

On top, they added blue spirulina for color, some fried shrimp (“camarón”), Kalix roe, tobiko (flying fish roe), some seaweeds like sea lettuce and sea grapes, and an emulsion that I’d say was codium. At the base of the plate, under the rock, there were small pieces of oyster.

I take Kalix roe to be the Swedish “caviar,” the roe of the European vendace (Coregonus albula), a freshwater salmonid; specifically from the Swedish city of Kalix, on the Swedish side of the Bay of Bothnia, where there’s an archipelago famous for producing this “caviar” with a distinctive taste due to the large influx of fresh water that the Bay of Bothnia receives from the rivers of Swedish Lapland.

The idea was to take the spoons and eat away.

A dish I remember as very aromatic, it smelled like Cala Montjoi! The taste of béarnaise was gentle, but I liked it combined with the seaweed and marine flavors. I found the rock a touch too cold; I always struggle with things that are too cold, although in this case the coldness dissipated quickly. The rock, despite looking like a sponge, crumbled; it wasn’t elastic like elBulli’s “sponges,” which is why I think they called it an “aerated rock” and not a “sponge.” Sea grapes, even if they add little flavor, are curious and fun for their texture. Discovering the delicious tender pieces of oyster beneath the rock was fantastic.

I found it curious to combine a béarnaise with seaweed, fish roe, and oyster, since it’s always been served with meats like Chateaubriand or beef fillets, though it has also been used with fish and vegetables. It also surprised me to eat it cold and in the form of an “aerated rock.”

Even so, the similarity between this “sea rock” and the “amaranth coral” is debatable. It’s like saying a black shirt dress and an LBD are the same. Yes, they’re both black dresses, but they have nothing to do with each other, one informal and daytime, the other a cocktail party dress. I mean they are two dishes with marine flavors, but technically they have nothing in common, apart from the fact that the “aerated sea rock” was a colder bite than the “amaranth coral.” Simply put, since I ate them in the same menu in October 2024 and only a few courses apart, it was easy to link and compare them because of their marine theme and aesthetics.

The “amaranth coral” is also a dish that more than one chef has liked and, even if they don’t copy the puffed amaranth technique for the base, we do find canapés that resemble Disfrutar’s coral quite a bit. We don’t have to go far to find a copy (or “homage” or “inspiration,” if you prefer to soften it), like the “Corali” I ate in May 2024 at Paco Pérez’s Miramar, the fourth of the nine aperitifs served.

I assume they call it “Corali” because, visually, it evokes the calcareous skeleton of marine coral.

There were spaghetti like or filamentous strands of various seaweeds on the shell of a zamburiña; the seaweeds remained rigid and were crunchy.

On top, salmon roe and tobiko (flying fish roe), although they didn’t specify, saying simply “different caviars.”

Also on top and again they didn’t mention it, there was a freeze dried codium foam (white, even though codium is green; who knows what they blend it with so it loses color). In any case, I take it they make a foam with freeze dried codium, not that they freeze dry the foam.

Over that foam, a bit of what looked like fresh wasabi and a little purple flower.

Over the seaweed base there was also a gelatin made of three seaweeds (the light yellow dots): laurencia, sea lettuce, and gracilaria.

There was also a gelatin with huitlacoche that doesn’t show in the photo.

Finally, “mareperla” (the succulent plant, not mother of pearl) which, honestly, I have no idea where it was or in what state (solid, liquid, or gas) they served it.

It was also meant to be eaten by hand like a canapé and, if you were capable, in a single bite; otherwise, half the ingredients fell off, crumbled, came apart, and dribbled everywhere, making a mess of yourself and the tablecloth.

Flavor wise, a citrusy mayonnaise and the salmon roe dominated. Texture wise, it combined the crunch of the dehydrated seaweed, the different crisp pops of the roes, and the creaminess of the gelatin, the foam, and the salmon roe when they burst, very pleasant creaminesses of different densities. A delicious canapé I would have enjoyed much more had I been able to manage it in a single bite.

At Miramar, in the same menu and also served as an aperitif, the ninth canapé was a dish titled “Marine Salad,” which also revolved around the same theme.

Even though they write Marine with a capital M, I understand it doesn’t refer to a proper name but to the sea.

They describe it as a “cupcake” of a transparent gelatin made from lemon peel and filled with brown crab and halophyte plants. Even though they didn’t announce it, it also had salmon roe (they said trout), orange tobiko (orange flying fish roe), yellow tobiko (yellow flying fish roe), and some “sea peas” that were spherifications based on a seaweed juice grilled over embers (the smallest spheres).

I don’t find it very serious to call it a “cupcake”; I don’t quite like that give me tartlet or a more classic name; we’re not in a café in the Sant Antoni neighborhood, for goodness’ sake!

An aperitif quite similar to the fifth canapé, the “Corali,” but without the crunch of dehydrated seaweed and, once again, with fish roes from very far from Cap de Creus.

All nine Miramar aperitifs were served and explained at once, resulting in a touch of saturation with so much information received in one go; I’d prefer they serve them one by one (with an allegro vivace tempo like at elBulli) or in two rounds. Besides, the three or four minutes of explanations alter the temperature, texture, flavor everything of each bite. An endemic ailment of fine dining; nothing new to say there. Just as I repeat myself by saying that, once again, the aperitifs were rather wishy washy something that doesn’t happen at Disfrutar. Fortunately, however, at Miramar they also had the marine intensity I expect from that restaurant, and that made me happy. I love starting with that fresh, pure maritime power so characteristic of Miramar at its best!

In short, aesthetically, the base of Disfrutar’s “Amaranth Coral” reproduces very well the idea of calcium carbonate forming the hard skeleton. The green color with red touches also seems very appropriate to me, since coral lives in symbiosis with microalgae that lend it those colors and, moreover, given that amaranth is white and they give it green and red hues with seaweed (codium).

Also, some corals can trap plankton and fish, so I find it very fitting to serve, on top, roes, seaweeds, and bivalves, in addition to boosting the marine flavor.

Therefore, I think it’s magnificently represented, it’s very good, and Disfrutar has made it possible for us to eat marine coral. I’d never have imagined it would be so delicious. A gemstone worthy of the finest jewelers. You could happily eat the whole reef!

October 11, 2025

Huset: The Northernmost Restaurant on Earth

We’re in Longyearbyen on Spitzbergen Island of Svalbard, above the 78th parallel. That’s as far north as the northernmost tip of Greenland. To get there, we sailed in the Hurtigruten ship Trollfjord for two days north across the Arctic Ocean from North Cape, Norway, which is the farthest north point of land in continental Europe. When you dock in Svalbard, you’re greeted by a sign warning of the dangers of polar bears.

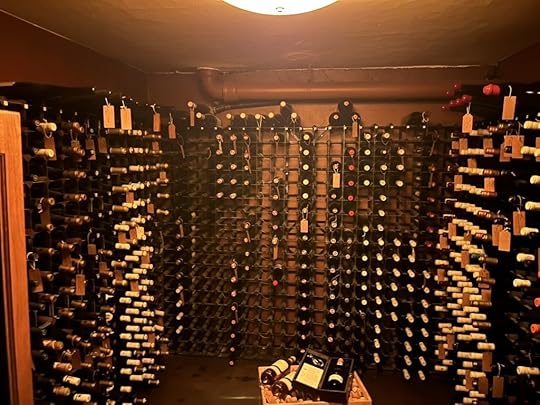

This wouldn’t seem to be promising territory for fine dining! But Longyearbyen is home to Huset, the northernmost restaurant on Earth. Amazingly, it holds one of the biggest and most extensive wine cellars in Scandinavia.

Huset, which means house, was built in the 1940’s as a community hall for the coal miners and their families who were the only residents of this remote island. By the 1970’s, the building came to house a restaurant to serve the growing population of what was still a one-company mining town. The menu then featured polar bear meat.

In the 1980’s tourists began to visit Svalbard, drawn by its bleak arctic beauty. Hroar Holm, Huset’s manager, came up with the idea of offering fine dining and began to collect wine. He insulated the basement set in the permafrost to provide ideal stable year-round temperature for a cellar. The concept is the same as the Svalbard Global Seed Bank which relies on the permanent cold to preserve samples of all the world’s agricultural seeds.

The collection grew to over 20,000 bottles. Today the list has more than 1000 different wines. I don’t think Michelin has visited Svalbard, but Wine Spectator did recently and awarded Huset their Best of Award of Excellence.

Over the years, Huset’s commitment to serious fine dining grew. Chef Alberto Lozano was recruited by Hurtigruten Svalbard to helm the restaurant. He’s from Albacete, Spain and brings some Spanish elements into his cuisine, but his palette has become first and foremost Arctic. He showcases not just Arctic ingredients, but local methods of preservation and preparation.

Chef Alberto Lozano

Chef Alberto Lozano

We sometimes talk about going to the ends of the earth to dine, but Svalbard is truly the end of the earth. It’s the furthest north land mass on the planet.

More than half of the archipelago is covered with glaciers. Here’s a shot I took on the fjord in which Huset’s town Longyearbyen sits.

The near complete absence of fertile soil and the extreme climate make growing anything here—except for a few herbs in a greenhouse—impossible. But there is much to hunt and forage.

Reindeer, seal, ptarmigan, mushrooms, various kinds of seaweed some herbs and berries—cloudberry, bilberry, mountain sorrel—head the list of indigenous Svalbard foods.

Fish are abundant. I asked one local about the fishing here. “It’s pretty good. We went out last week and I got about four or five hundred.” “What do you mean?” I asked. “Four or five hundred kilos,” she explained. On rod and reel. In a couple of hours.

Our dinner at Huset was a fourteen-course tasting menu. We were brought glasses of a California sparkling wine as soon as we sat down. I generally choose standard rather than prestige wine pairings, but interested to see what their famous cellar held, I went for their top-level pairing. I was somewhat disappointed to see that only about half of the selection came from their cellar collection and half were recent acquisitions. But nevertheless, there were a good number of wines in the pairing that I especially enjoyed.

The amuse bouches began with Svalbard Cold Cuts and Bread.

Reindeer heart, smoked and dried, and reindeer chorizo were served with a black shallot paste and a Pan de Aceite, showing the chef’s Spanish roots.

Dry aged reindeer neck

Dry aged reindeer neck

Local beer sourdough bread came with butter cut in the shape of a ptarmigan and infused with that bird’s dried and finely ground meat. I loved the bread but found the butter an unsuccessful attempt to combine a local ingredient with a foreign one. Ptarmigan are native to Svalbard but butter, of course, is not.

The reindeer chorizo, on the other hand, used Spanish paprika that the chef brought from a trip to his home to make an exceptionally flavorful and enjoyable local/foreign sausage.

I’d like to include here the chef’s description of the care they take to use every part of the reindeer they get from a local hunter and trapper:

Once the reindeer arrives in our kitchen, we hang the meat for an additional two weeks, building on the time it spent in the trapper station. We then carefully separate each muscle to ensure the highest quality throughout the process.

The finest cuts are vacuum-sealed and frozen, while some legs undergo a traditional Spanish ham curing method, which takes at least nine months. This involves curing the meat in salt for 14 days before hanging it, covered in Spanish paprika, to develop rich flavours.

We transform the neck into cold cuts, and with the leftovers, we create chorizo, pâté from the liver, smoked heart, and brined air-dried tongue—delicious when fried.

Finally, we roast the whole carcass to produce a rich demi-glace. Any leftover fat is repurposed in our kitchen or shared with our friends at Green Dog [a Svalbard dog sledding service company.]

This meticulous process allows us to honour every part of the reindeer while bringing the authentic taste of Svalbard to the table.

Next among the starters came Rype (the local name for ptarmigan) served two ways: pralines of ptarmigan leg meat prepared confit-style with black currant compote, and “anchovies,” crafted from breast muscle rillettes, preserved in Røros butter, and served with a lacto-fermented tomato sauce on toasted seed bread, replicating the classic anchovy experience. On top of the “anchovies” were seeds found in the bird’s crop, a local traditional practice.