Michele Sharpe's Blog

November 10, 2025

Who Will Win the Booker Prize?

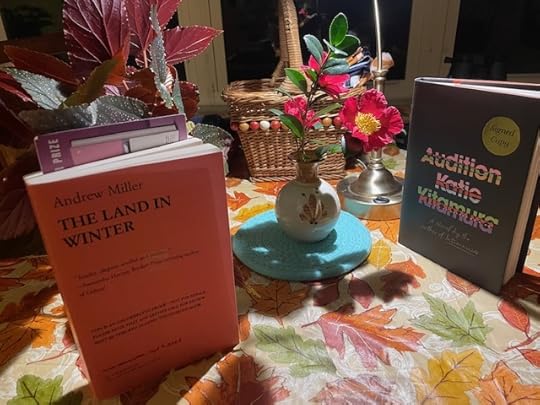

I’ve only read two titles on the Booker Prize short list, The Land in Winter by Andrew Miller and Audition by Katie Kitamura, so there’ no telling which book will win from my perspective. It’s the big night!

Audition was a First Editions Book Club pick at my local bookstore, The Lynx, a project spearheaded by writer Lauren Groff. The Lynx has been around now for a couple of years and its brick-and-mortar storefront and patio have added so much to cultural and social life in Gainesville, Florida. And, of course, Lauren and her team are fabulous curators, holding frequent book club meetings, author events, and writing classes.

Audition is not “my sort of book” for a few reasons — it’s based in NYC, the setting for too many novels IMHO, the prose is crisp and unadorned, and its protagonist has respect for psychiatry. But it is “my sort of book” for other reasons — its protagonist is a woman and the whole second half of the book is a killer plot twist. The book is, for a dinosaur-brain like mine, experimental and a bit inaccessible, but it was still a compulsive read. Once I got to the second half, I couldn’t put it down. And, It has things to say about motherhood that seem unique in literature to me, except that I never read books about motherhood, so how would I know?

The Land in Winter came to me via Autumn Toennis, a writer and an editor at Europa Editions who sent an ARC (advance review copy — because I write reviews, publishers often send ARCs to lucky me) with a note that said “Andrew doesn’t waste a sentence.” She’s right about that. Every sentence contributes to the plot, characterization, setting, or themes, but the prose is also elegant, even delicious. It’s a historical novel, set in England in the 1960’s during a brutal winter. As a Boomer, I resisted the idea that the 1960’s are so long ago they are historical. Reading it, though, was like diving into a not-too-cold pool. The opening propelled me underwater through the deep end and into a place of rest, where I could float on my back and look up at the clouds. It’s a novel reminiscent of Iris Murdoch’s finest work, where characters interact with each other on deep levels even when they are hiding truths from each other.

The Land in Winter is not “my sort of book” because it’s written by a man. Decades ago, I began avoiding contemporary fiction written by men because of my irritation at the inevitable misogyny. So many books, so little time, as you know. As a young reader I excused favorite 19th century writers like Tolstoy and Dostoevsky for their patriarchal alignments because they came from a different time. Kind of silly, right?

I recommend letting others choose your books sometimes. As it turned out, The Land in Winter is exactly my kind of book: that restrained, elegant British tone, that peculiar British humor, the stiff upper lip characters with tormented psyches, and a sense of land that is conscious of its own history.

So, which book won the 2025 Man Booker prize? Find out here.

November 5, 2025

Kvelling over my stepdaughter’s work in the NYT

Honestly, every piece Sachi Kitajima Mulkey writes from the Climate Desk is even more incisive and assured than its predecessor.

This one is about an Alaskan indigenous community working to preserve its history against the multiple threats of climate change.

October 20, 2025

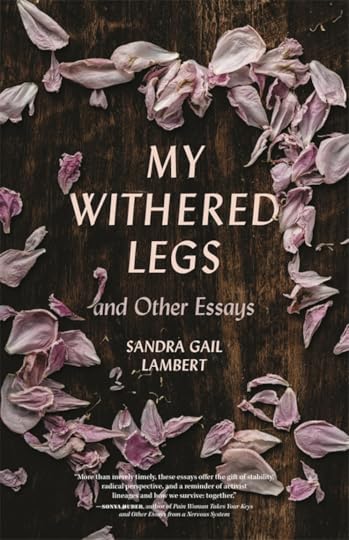

When Writers You Admire win a Lammy

My dear friend Sandra Lambert planned a birthday party for her wife, Pam, and the date arrived shortly after the 2025 Lammy Awards were announced. At the party, I was still thrilling from the news that Sandra’s essay collection WON A FUCKING LAMMY. The party felt like an episode of the Twilight Zone because no one was talking about her big win. Early on, when only a few guests had arrived, my self-control evaporated and I jumped up and down, yelling SANDRA WON A FUCKING LAMMY!

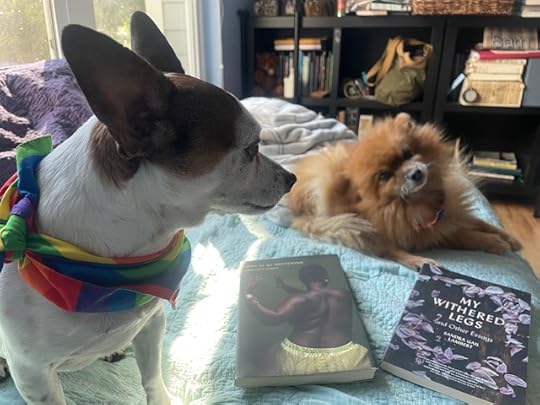

During the rest of my time at the party, I talked about what other people were talking about: the lack of rain, camping, Lucy, the cute middle-aged chihuahua that Sandra and Pam were fostering-to-adopt, and Andrew Fabian, Pomeranian, who is in this photo and is my current super-senior foster dog. He’s also called “Benzo” for his calming effect on humans. He nicely snuggled on my lap part of the time.

Chronic illness and advancing introversion makes parties uncomfortable for me. By the time celebrations were in full swing, it was time for home, sweet home.

But still, no one was talking about Sandra’s Lammy Award. I opened the door to leave quietly, but then shouted “Let me say one thing before I leave: SANDRA WON A FUCKING LAMMY!” Shutting the door, I saw glasses raised and heard universal cheers for Sandra. Finally. Sheesh.

One description that’s been applied to me all my life, in theory as a compliment, is “You’re so laid back.” It’s never set that well with me. Laid back in the grave? Laid back like a pillow princess? Maybe chronic illness has made me appear flat. Inside, I’m a roiling stew of eccentric thoughts, bizarre ideas, and chunks of beloved books.

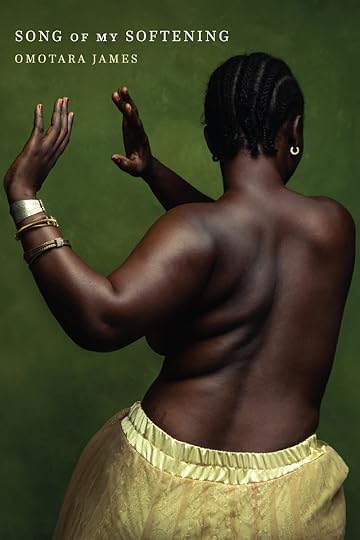

Please celebrate with me! Sandra’s book, My Withered Legs and Other Essays won first place in lesbian memoir/biography, and Omotara James’ poetry collection, Song of My Softening, won first place in lesbian poetry. I know Omotara from social media and have followed her work for a few years. If I’d been at her wife’s birthday party and no one was talking about her Lammy, I’d have been the same mouthy bitch.

The Lambda Literary Awards have been around since 1989. Submissions for the 2026 awards are open (NOW!) from September 15 – November 21, 2025.

September 5, 2025

Gems from my Sealey Challenge fail

I began this year’s Sealy Challenge inspired by poet friend Linda Cue who engages with the challenge every year. Although reading a whole book of poetry in a day is clearly too much for me, the challenge has made me read more poetry than I usually do, and that’s to the good for my mind and heart.

Re-reading is my preference when it comes to poetry.

One book that I read and re-read in August is the newly released collection SOFAR by Elizabeth Bradfield. This expansive collection teems with the panoply of life on Earth, spreading the news that attentiveness to the “more than human” world offers relief from bland fascist notions of uniformity and extraction.

Moments of intense joy come from such attentiveness. But moments of stunning grief come from attentiveness as well, and in some poems, attentiveness brings both joy and grief. “Dispatch from this Summer,” with its hermit crab form is one of these. The crab makes a house for its soft body in a discarded shell; in the form, one narrative holds the other, but the form is not a comparison giving one story ascendancy.

The “house” narrative concerns the invasive gypsy moths’ decimations of trees by “unrelenting mastication” that results in a rain of “a constant heavy frass.” Still, the forest holds beauty

. . . If you can stand to walk a narrow path through the leafless

forest, you can arrive at a circle of water that will allow your body

to be beautifully held, whoever you are. It’s true, you’ll have to return

by the same path . . .

The body held in this poem’s house is a host of vulnerable bodies, the “Florida dancers,” who were killed in the 2016 mass murder at Orlando’s Pulse nightclub, the dozens more who were injured, and the community who witnessed. The naturalist notes that taking the journey to be “beautifully held” means traveling back through the “apocalyptic trees.” In other words, through a shit storm.

“Dispatch from this Summer,” and this book, and Bradfield’s work as a queer poet and naturalist, all have an urgent significance to me. We live in dangerous times, where gross homophobia is pushing its way onto national, state, and local levels, even into my beloved Florida’s liberal enclaves, like Orlando, where a rainbow crosswalk adjacent to the Pulse Memorial was erased overnight. In Gainesville, my home town, city councilors voted unanimously to obey the state’s order to erase our rainbow crosswalks. Fuck that noise.

Next up, a book that allowed me to further indulge my re-reading habit: A Glossary of Snow by Feral Wilcox. The collection is a true glossary that defines emergent terms for the diversity of snow.

Feral and I have been friends for twenty years, and so I’ve had the pleasure of reading her imaginative yet sensual work in various incarnations. These poems are some of her most musical, making excellent use of all the sensory strategies she is intimate with as a poet, musician, and visual artist.

Even in the collection’s prose poems, the music is dense and fecund. From the first stanza of “Daughter of Pearl”

daughter of pearl

a hard snow born from a harder snow, under the hard shell of a dull grey sky

In an era of hollow dolls lost in warspell, sororities of the pearled-up poor, glamour girls pushed from great depressions into chorus lines, high kicks and cattle calls of drunken flesh swirled in a syrupy cocktail of dresses, pleats and flounces, cleavages, pearlescent romances, crooning juniors of blue-blood seniors, shills of swindlers, big brass boards of hidden hitlers melting their hot silver spoons into shrapnel kisses milked from winter skies uddered with promises, falling, falling as tin cups filled with snow rattle off into the steaming rubble of true love, I’ll be waiting for you, dear, with home appliances and recipes, the basics of home-economics, the rich give a gift to the poor, another war.

Part indulgence, part politics, part fortune-telling, and all art, A Glossary of Snow is another queer book of the present moment.

Thanks for reading So many books, so little time! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

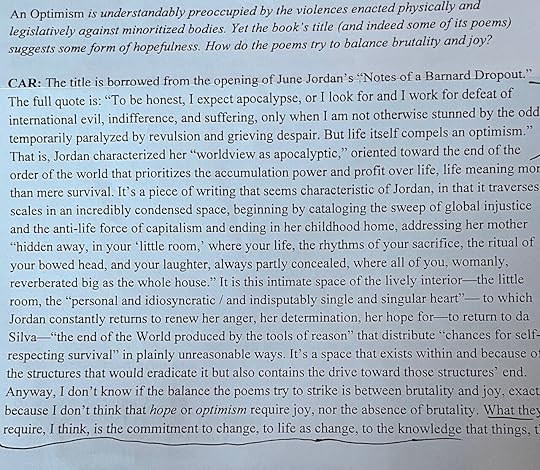

Cameron Awkward-Rich’s book, An Optimism, is thrillingly intellectual while being achingly emotional. Quite a feat. Big thanks to Gabriel Fried over at Persea Books for the ARC (Advance Reading Copy), which included a transcription of an interview with the poet. I read the interview first; in it, Awkward-Rich mines his experience teaching an undergrad class, “Poetry in/as Black Feminist Thought” along with his cultural criticism work for exemplars of his ideas. Here’s a screenshot from that fortunately long interview, where he explains the title of his book as borrowed from a line of June Jordan’s:

The poems enact the idea of cultural criticism, using disparate texts ranging, for example, from the work of Pauli Murray, to Neverland and Peter Pan, to the opening sentence of Charles Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities as subjects. Often, there’s a young speaker who longs for mirroring: to see someone like himself.

One surprising-to-me trope is the character of Odo from Star Trek: Deep Space Nine, who is “trapped between forms.” In his natural state, he’s a gelatinous mass, but he is a shape-shifter who assumes the appearance of anyone and anything. Change is Odo’s baseline. Even I, a cis woman, can see parallels here to trans experiences in a transphobic world.

From one of several poems titled “It Was the Best of Times, It Was the Worst of Times”:

I didn’t know yet that it was possible, to be, like that, unmade & madeJuly 9, 2025

On joan larkin’s old stranger

Does the the brevity of lyric poetry appeal to Millennial and Gen Z readers? The turns from narrative to lyric modes in Joan Larkin’s new poetry collection Old Stranger may be attractive to them then, but the poems will also resonate with readers who’ve attained longevity. An octogenarian, Larkin has been celebrated for blending lyric and narrative elements in her work and for nudging her poems toward resolution and epiphany. Her reliance on the lyric mode in Old Stranger intensifies as the collection progresses, while not entirely abandoning narrative. The superseding of narrative by lyric elements tends to form its own arc in a story about aging through perceptions of time and the past.

Larkin was born in Boston, a few months before the 1939 invasion of Poland that set off World War II. Eighteen years older than I, she is a writer I’ve respected as an elder who is always a generation ahead of me in experience, and in the wisdom that may come from it. I’ve followed her work for decades, beginning in the 1970’s at New Words Bookstore in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where I began seeking out queer and feminist literature as a teen. Now, almost 50 years later, Larkin’s poetry continues to create beauty and delight while offering wisdom as I enter my elderhood.

It’s uncommon for poets to have 50-year publishing careers, even now that life expectancy has grown over the past century. If a poet’s early work establishes their personal mythology, as Larkin’s did, what happens to that mythology over a lifetime? Does it grow stale, or get reassessed, or reinforced, or even abandoned? In Old Stranger, the subjects of Larkin’s foundational narratives – rape, abortion, miscarriage, coming out as lesbian, getting sober – are often reshaped through the lens of lyric, which emphasizes the distillation of seemingly truthful perceptions rather than the arc toward them. This turn to the lyric is a Swedish death cleaning of sorts that sweeps events to the side and prioritizes images of insight and emotional truth.

Of course, neither lyric nor narrative modes exist in separate bubbles. There’s a term in poetic discourse for combining them: the lyric-narrative poem. During the first months of an MFA program in the 1990’s, where I was struck by how much I did not know about poetry, “lyric-narrative poetry” especially confused me. Any initial recognition of ignorance may often play a part of the narrative arc of achieving wisdom, but I did not achieve any lasting wisdom on this point. Thirty years later, Old Stranger has revived my old confusion, especially in its poems treating narrative time as both rigid and flexible. Now, though, I can at least see the assumptions that stand in my way: that the lyric exists outside of time, but that narrative relies on time to be understood, and time relies on narrative to be parsed.

A disregard of narrative time first appears in the book’s fourth poem, “The Body Inside My Body,” where a second body, belonging to the speaker, asserts its power. This body wants “the breath it lost trying to escape / that afternoon in Hell’s Kitchen.” With short, declarative sentences establishing her authority, Larkin convinces me this alter-body can get that breath back. The poem offers hope to anyone with traumatic memories who, like the second body, “[h]as had it up to here with the scalding” and “wants the whole carcass unburied.” But the uncovering and implied dissection of the carcass of the past is just the beginning. The carcass’ obliteration is what this alter-body is after, as it wakes in a gothic setting that “any body wants,” where vultures “hiss in the low branches,” ready to do what vultures do. Who wouldn’t want painful events and their sequelae picked apart, swallowed, and annihilated by a vulture’s acid-bath gut?

Read the full review at On the Seawall

March 10, 2025

Reviving the Right to Repair

Way back in the 20th century, I lived in New England, where the phrase “Mickey Mouse” was slang for a slapdash repair accomplished with whatever might be at hand: duct tape, empty soup cans, wire hangers, pepper and BB pellets. My recently published essay, “Mickey Mouse Fix,” in the swanky online journal Dorothy Parker’s Ashes tells the tale of how I fixed my 1972 Plymouth Duster with these magical items., and how I later repaired a 2012 Honda Odyssey with the 21st century’s best slap-dash repair advance, the zip-tie.

“Mickey Mouse,” or just “Mickey” could also be used as a verb, as in “I mickey-moused that motherfucker.”

All profanity aside, the right to repair is a serious issue. Throwing away our broken things and buying new ones serves capitalism and its billionaire class, not us, the ordinary folks. It also creates dangerous waste products. Some states have enacted right to repair laws covering consumer electronics and appliances. In other states, legislation is pending. A national bill was recently introduced.

Get your Mickey on!

February 17, 2025

What to read in 2025?

First up, warm praise for a reading method new to me in 2024: slow reading.

Like the slow food movement, slow reading encourages the practice of attentiveness to the moment. I may have achieved dog-consciousness as a slow reader.

As a happy 2024 follower of the Footnotes and Tangents slow read of War and Peace, one chapter a day of this humane novel brought me all the pleasures of a well-plotted story, plus unexpected insights into human nature and history. The book has gobs of contemporary political and emotional relevance, and the international reading community’s commentary and extra info provided by leader Simon Haisell is a treat. For a busy person who wants to maintain a daily reading practice, consider a subscription to one of the many slow read offerings out there on the benevolent side of the internet. I wholly recommend Simon’s several 2025 offerings as he is well-informed about the books he chooses, he has an international following of readers who encourage friendly, diverse discussion of the books, and he is an excellent, reliable manager. I’m participating in the Wolf Hall Trilogy slow read this year.

Here’s some thoughts on the best books I read in the summer of 2024, and the kinds of readers who might appreciate those books.The most unusual book of the summer for me was How Far the Light Reaches: A Life in Ten Sea Creatures by queer science journalist Sabrina Imbler, who juxtaposes their own growing up story with the stories of unusual marine organisms. The result is a series of stunning extended metaphors that undulate between the wonders of underwater life and the wonders of human consciousness. An excellent selection for readers who enjoy nature writing, magical metaphors, and the macro-micro entanglement of the big world and the individual psyche.

Double trouble: I read one book — Find Me — by Floridian Laura van den Berg and immediately requested another — State of Paradise — from my library. Both are quirky stories with low-key incorporation of supranatural events. Both books have an original voice, an original premise, and a full-throttle plot, and are great choices for those who love Florida in all its other-worldly diversity.

I’d never heard the name “Miranda July” before picking up All Fours, so the book must have been endorsed by a credible-to-me person somewhere on the benevolent internet. The narrator is perimenopausal, which was its own special delight. The book probably struck me as particularly imaginative because I knew nothing about the author while reading it. The plot is compelling, and the sex scenes are detailed, diverse, and hot, hot, hot. Read this book if you love sex.

Liars by Sarah Manguso was recommended by Lyz Lenz in her crucial yet hilarious stack, Men Yell at Me. I know I stayed up past my bedtime reading Liars because it had a propulsive plot, but I can’t remember a fucking thing about it beyond that. Probably says more about me than about the book. A good choice for those interested in the state of American cis/het marriage and books meant to be read at an astonishing speed.

In her memoir Wishing for Snow, Minrose Gwin writes of growing up with and rediscovering her schizophrenic poet mother, Erin Taylor. Closely observed on internal and external levels, the book is strikingly honest, and it incorporates many of Erin Taylor’s poems. Gwin is new to me, and I’m planning to read more of her graceful work. Read this memoir for the beauty of its language and to know more about mother/daughter relationships, schizophrenia, and poetry.

Consent by Jill Ciment reviews and revises her first memoir, Half a Life. Why? Because the first one didn’t sufficiently interrogate her relationship with and marriage to artist Arnold Mesches. The couple met when Mesches was a 40-something married man with kids and Ciment was his 17-year old art student in a situation that would be described today as sketchy in terms of the power dynamics. Ciment is such an authorial powerhouse in both memoirs, though, that the question of consent is nuanced and perhaps unanswerable. A book for anyone who enjoys or needs the skill of accepting opposing versions of reality.

Jane Satterfield’s phenomenal poetry collection, The Badass Brontës, is a must read (IMHO) for all Brontëphiles. Satterfield writes of her own encounters with Brontë texts, as well as how she imagines interactions among and between sisters Charlotte, Emily, and Anne, both in the past and in a time-optional afterlife. The surprising rhythms of the poems demand attentiveness, like curveballs and reversals in any context do. Perfect for poetry lovers and anyone fascinated by the Brontës.

Jesmyn Ward’s most daring book so far, Let Us Descend, is a book that makes me wish for a long enough life to read everything she will write in the future. It’s daring in the steps it takes into the spirit world, in its visceral detail of the suffering of enslaved people, and in the cascades of inter-related images it uses like a net of jewels to gather the best parts of being human. I read it first in February of 2024 and again over the summer. Everyone should read this book for its power, beauty, and humanity, and, given our in our current world situation, for its combination of cleansing rage and miraculous compassion.

If you like to buck trends, consider reading a memoir, since the powers-that-be never tire of telling us that memoirs are hard to sell. This year, I interviewed two authors with memoirs that came out in 2024, and I recommend both.

Penny Guisinger’s SHIFT: A Memoir of Identity and Other Illusions explores the power of change in the physical, emotional, and political shifts that occur within (and outside of) the memoir. Gusinger fell in love with a woman in her Downeast Maine community, ended her heterosexual marriage, and continued to parent her two children, who were quite young, and to work in a high stress job. The shifts required to make all this happen are set against the tumultuous context of Maine’s on-again-off-again Marriage Rights saga from 2011 — 2013. It’s also filled with that subtle Maine humor:

“I had a beer bottle wedged into a mesh cup holder hanging below the arm of my chair. I got right to work peeling the label from the exposed section of glass. I stayed on task throughout the conversation.”

Who hasn’t peeled a label off a sweating bottle during a hot, high stakes moment? This understated humor is one of the many elements in SHIFT that captured my heart. The book is also an intellectual treat, examining non-linear time in the context of personal and political “shifts,” including coming out as lesbian.

The book’s haunting relevance to the past decade’s Twilight Zone attacks on individual rights across the United States makes it a must read for understanding the current American political moment. Penny and her wife Kara lived through the approval and subsequent repeal of marriage rights on the state level in Maine. Their courage in managing their personal, family, and professional lives in the shadows cast by the bullshit repeal is just the sort of stubbornness so many of us need now.

SHIFT is a rare confluence of passion, humor, politics, and personal insight. Highly recommend. For more about the book, check out my interview with Penny in CRAFT.

In Chris La Tray’s memoir Becoming Little Shell: A Landless Indian’s Journey Home, the recovery of the Chippewa identity his father hid happens as the Little Shell Tribe of Chippewa Indians endures the long process of achieving Federal restoration. The search for a hidden personal past is juxtaposed with political demands for restoration of a historical past. The memoir’s scale is vast, and readers will come away with insights into Chris’s struggles and the struggles of his tribe, and others, against the colonial violence and machinery of the United States. For more about this remarkable memoir, check out my essay/review for On the Seawall.

There’s much to learn from this book about the many paths resistance may take, about respect for others’ choices, and about the recursive nature of oppression. Plus, the book is a beautiful love poem (Chris is currently the Poet Laureate of Montana) to the High Plains region.

Wishing you a radical year of reading!

April 19, 2024

Rape Conception: The Second Victim

Do you remember how difficult it can be to talk about a subject when there’s no language or terminology for your own experience? Or when you’ve not yet found the language? Several years ago, Daisy (she uses this pseudonym to protect the identity of her mother) began posting on Twitter under the username rapeconception, offering necessary terminology for the experience of being conceived by rape. We chatted online, and then over Zoom during the first years of the pandemic, comparing the similarities and differences of our experiences.

My mother was fourteen when she became pregnant with me; Daisy’s was thirteen. We were both put up for adoption, me in the U.S. and Daisy in the U.K. Daisy’s a Black woman who was adopted by a White family, and I’m a 97% White woman adopted by a mixed Jewish and Catholic family — which, believe it or not, was called a “mixed marriage” in the mid-twentieth century.

Our biological fathers were both well into their adulthood at the time of our respective conceptions. In 2015, a DNA genealogist determined mine was one of two brothers, the younger of whom was ten years older than my fourteen-year-old mother. I’ve sent letters and emails to the brother who is still alive. These have gone unanswered. I’ve imagined strolling by his house and asking him about his garden as a way of getting him to talk to me. All I do is imagine; I take no further action.

Daisy’s father was also an adult, much older than her 13-year old mother. It takes a person of courage to bring another person to justice, whether through the law or through a private conversation. I am not that person, but Daisy is. Her activism on behalf of rape-conceived people changed the law in the U.K.

Daisy worked with the Centre for Women’s Justice to develop “a set of proposals that would recognise children conceived in rape, legally, as victims of crime, and entitle them to specialist care and support.”

So how many victims are we talking about? The proposals that became Daisy’s Law were inspired by Daisy’s personal experience and activism, but they relied on research and data as well. One study showed that in 2021, for example, between 2,080 and 3,356 people were conceived via rape in England and Wales. This estimate was based on calculations of the likelihood of conception after intercourse in rapes reported to law enforcement.

Rape is a notoriously underreported crime. A 2018 study in the United States found that 2.4 % of women reported experiencing rape-related pregnancy. The number of these pregnancies that women are forced to carry is likely on the increase in the United States. A 2024 research letter published by the Journal of the American Medical Association estimated that 64,565 rape-related pregnancies have occurred in the 14 states that have enacted abortion bans since the U.S. Supreme Court gutted abortion rights in 2022.

The limited research on rape conception has shown an increased prevalence of negative developmental and educational outcomes for children conceived by rape. Daisy’s Law now recognizes rape-conceived people as victims in U.K. rape cases and makes victims’ benefits available to them. She tells her story of moving from awareness to activism with courage and compassion in the Audible documentary podcast, The Second Victim, released in November of 2023.

The Second Victim begins with Daisy’s early memories of being a Black girl adopted by a White family and living in a White community in England. At a very young age, Daisy struggles with a sense of disjointedness, the paradox of being singled out and also invisible. When she begins asking questions about her birth parents, she senses another complication, one that’s under the surface of her visible differences from the White people surrounding her, but she doesn’t quite have the language for it yet.

Daisy narrates her own story in her intelligent and expressive voice. She’s joined by people who have been close to her during her search for justice, who add their voices and observations. As someone unfamiliar with podcasts, the listening experience took me a bit by surprise; the added sound effects made the experience more like a film than an audio book by encouraging my brain to visualize conversations and events. Daisy’s story is dramatic in its scope as it tracks her journey through closed doors and roadblocks to find her truth and to achieve some measure of justice and support for people who were born from rape.

Like rape itself, rape conception has long been stigmatized, underreported, and kept a secret. Unveiling the secret brings it into the light of examination, which can benefit everyone. Thank you, Daisy.

February 22, 2024

Aging in place

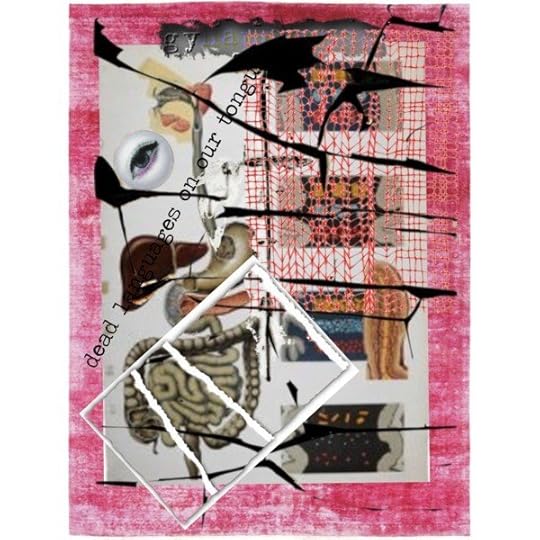

Jill Khoury’s cover art for Issue 107 of Rogue Agent: a square surrounded by a pink border and splashed with streaks of black or brown paint. At the top, the word “gyna-“ disappears under a piece of loosely-woven peach-colored fabric that covers the upper right part of the image. The words “dead languages on our tongues” appear diagonally across its left side. The rest of the image is made up of several pictures including an eye, a digestive tract, lungs, a liver, and bursts of colored pills.

Image and alt-text by Jill KhouryIsn’t this cover image fabulous? As in like a fable, a fairy tale, a story. Collage art always captures my attention because of the work it does in juxtaposing images so that viewers can assemble a story to go with it.

Winter can be a difficult time for me and my old bones. My poem, “Aging in Place,” which appears in this current issue of Rogue Agent, reflects some of that difficulty.

Do you ever want to give up on healing? Why or why not?

My future snaps like a rusted latch

and hasp. I live happily severed after. . . .

https://www.rogueagentjournal.com/msharpe

January 18, 2024

Reviving Delight in Russian Literature

Agnes, my current foster dog, with her copy of War and Peace.

Agnes, my current foster dog, with her copy of War and Peace.2023 was the year of resuming my delight in Russian novels. Nearly fifty years of intermittent longing for a treasured copy of The Idiot by Fyodor Dostoevsky had passed; my first lover had torn and sliced the book into pieces and scattered it around my neighborhood. One day in 2023, I realized the same edition might be available through the internet. It was.

Inviting a powerful object into your life can open a door. Shortly after the replica of my long-lost book arrived, I received an assignment from Foreword Reviews to review the Russian novel A Volga Tale by Guzel Yakhina, and from there came the adventure of writing a longer, hybrid essay/review about A Volga Tale for On the Seawall. From there came learning of the Footnotes and Tangents community’s 2024 slow read of War and Peace, which I’m participating in now.

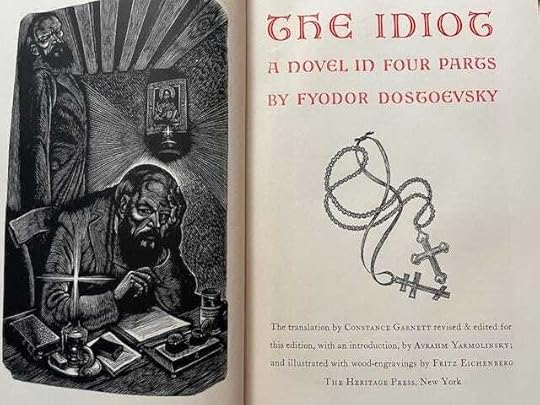

Aside from Nancy Drew mysteries and books about horses, there weren’t a lot of books in my childhood home, but a temporary subscription to a book club brought two new adult novels in. These were hardcovers that came in their own fabric-covered slipcases, which impressed me as classy. One was The Idiot, thick, heavy, and illustrated, a book that when open had a 14- by 10-inch footprint that could be draped across your lap like a small, sad dog. The Idiot’s illustrations, by Fritz Eichenberg, were wood cut prints, dark background and foreground with slashes and streaks of light outlining characters and their settings. The characters’ faces, for the most part, were contorted with emotion, like teenage life.

Title page of The Idiot with wood cut print of a struggling and divided Dostoevsky

Title page of The Idiot with wood cut print of a struggling and divided DostoevskyI first read The Idiot several years before the destruction of my treasured copy. If you’re not familiar with the book, one way to summarize the novel is to say Dostoevsky wanted to write about a “wholly good man.” The novel’s good man, Prince Myshkin, is afflicted with a seizure disorder, not unlike Dostoevsky himself, who became epileptic as an adult.

This is a recurring trope — at least in certain stories — that moral perfection for men comes with injury to the body, or a physical difference from others. Think of the blinded, one-armed, and ethical-at-last Rochester at the end of Jane Eyre. Or, perhaps, Jaime Lannister from Game of Thrones, who loses his hand and briefly subscribes to a moral idea about community. Or Jesus.

When, in 2023, I opened the package with my new copy of The Idiot and slid the book from its classy slipcase, the slipcase came apart. The book itself was in better shape, and its heft brought back the sensation of being immersed in literature and the suffocating weight of a violent love affair. Being underwater feels powerful when I can swim, but frightening when I can’t swim away. But this is the story of reading, the one with a happy ending.

Nostalgia and excitement about something wholly new filled me in 2023 as I read A Volga Tale. The lush and rhythmic English translation by Polly Gannon reminded me of Constance Garnett’s translations of 19th century Russian fiction. Here were the sonic pleasures of subtle meter and rhyme, the roll of language as it meets with thought. Like Dostoevsky’s work, A Volga Tale employs magic realism and is concerned with “the relationship of the country and personality.”

The novel’s central character, Bach, is an ethnic German who lives on the Volga, a descendant of one of the many Germans encouraged to relocate to Russia by Catherine the Great. Bach is a village schoolteacher who loves languages but becomes speechless when he must face the Russian brutality that robs him of his wife and leaves him a daughter, Antje. With Antje, he conducts “a perpetual, gravely serious conversation in the language of breath and gesture and movement. Each of them was like an enormous ear, poised to listen and understand the other.”

Coming across familiar ideas brings the pleasure of recognition, and this can open my mind to new ideas, as if I’m also an enormous ear, poised to listen. What was new to me in Yakhina’s novel was her concern with “the issue of internal freedom and its ratio to the external freedom.” In Dostoevsky’s novels, freedom is sometimes granted through religious faith, but more often, it’s the characters’ own thoughts and actions that free them or shackle them, creating liberating epiphanies or inescapable prisons of remorse.

Yakhina’s outsider status as an ethnic Tatar woman in Russia may have contributed to her insights about the pressures of external freedom or lack thereof on a character’s internal freedom. In the early days of the Bolshevik Revolution depicted in A Volga Tale, the young people of Russia are swept up in a new life of communal effort for the communal good. Bach’s daughter Antje grows strong, happy, and free of gender constrictions with her comrades during that brief, pre-Stalin era.

The young women in The Idiot don’t experience such freedom; the main characters exist at opposite ends of literature’s traditional womanly spectrum: Aglaya Ivanovna, the virgin daughter of a general, and Nastassya Filipovna, an orphan, sold in some vague way to a wealthy man. By the time I read The Idiot, I’d already learned about the two ends of the womanly spectrum from Jane Eyre — the very good, innocent woman (Jane) at one end, and the very bad, experienced woman (Bertha) at the other end.

As is the habit of many readers, after the last page of A Volga Tale, I looked for more books by Guzel Yakhina and found her debut novel, Zuleikha, which is based on her family stories about life under Stalin and in the Siberian gulags. It is a spellbinding, cross-country epic, and because it won numerous literary awards around the world, I was able to get a copy from my local library. I’m hoping that Yakhina’s third book, a historical novel about the 1921 famine in Russia, will be translated into English soon.

In November of 2023, as if reading my mind (or my clicks, which are similar), Substack alerted me about a 2024 slow read of War and Peace. It had been decades since I read that book. Was it a coincidence that the used bookstore in my part of town had a paperback copy of War and Peace in the Constance Garnett translation, the translation I’d read in the 1970’s after The Idiot sent me in search of more Dostoevsky, which took me to the library and The Brothers Karamazov, The Possessed, Crime and Punishment, and later to War and Peace? Is it reckless of me, that with so many books and so little time, I turn to re-reading at least once a year?

Now it’s 2024, and I’m (re)reading a chapter a day of Tolstoy, thanks to an algorithm and to Simon Haisell and his Footnotes and Tangents group. Tolstoy’s words sound both familiar to my ear, and wholly new; I’d forgotten how funny he can be. This may be an even happier year than last year, when the used but new-to-me copy of The Idiot sat on my lap like a small, sad dog. Its pages felt soft, and miraculously whole.