Mark Winne's Blog

January 5, 2026

Radio Food!

Food Sleuth Radio’s Melinda Hemmelgarn

I had the privilege in December to be interviewed by Melinda Hemmelgarn, the originator, instigator, and officiator of Food Sleuth Radio. With over 700 episodes spanning some 17 years, Melinda has faithfully, if not religiously executed the duties of an investigative registered dietitian to inspect, dissect, and occasionally reject nearly every element of this nation’s food system. Her co-pilot, producer, and husband Dan Hemmelgarn staffs the controls of their recording studio, and together they plot their broadcasts from an abandoned SAC missile silo somewhere under the central plains of Missouri. More likely, you’ll catch them in the heady environs of Columbia where they hang out with non-profit, listener-supported KOPN Radio which pumps the unrestrained voice of truth from the banks of the Mississippi to the shores of the Missouri. When conditions are right and sunspot activity low, KOPN distributes the words and wisdom of Melinda and her expert guests to over 50 outlets across these United States.

With more good fortune than I deserve, Food Sleuth Radio gave my new book The Road to a Hunger-Free America a generous amount of airtime to dig deeply into my story, the book’s story, and how it might enrich your story. Though listening to these two, 28-minute interviews is not an allowable excuse for not buying the book, they provide what I think is a great introduction to its themes and the 23 essays that give life to this wonderful adventure we call the food movement. And not only did Melinda do an exceptional job of enabling me to unspool my tale, she used her interrogation skills to extract some never before told facts about me!

Tune in here for Part One: PRX » Piece » Mark Winne, MS, food justice advocate and author of The Road to a Hunger-Free America: Selected Writings of Mark Winne. (Part 1 of 2)

Dial in here for Part Two: PRX » Piece » Mark Winne, MS, discusses his latest book, The Road to a Hunger-Free America: Selected Writings of Mark Winne. (Part 2 of 2)

And to read the entire unvarnished story, you can purchase the book here: The Road to a Hunger-Free America: Selected Writings of Mark Winne: Mark Winne: Bloomsbury Academic – Bloomsbury

December 21, 2025

Will Christmas Bring Light or Darkness to Palestine?

I’m not one to obsess over the historical antecedents of oppression. Perhaps because I take it as a given that civilization’s conflict-ridden unfolding has and always will be a dialectic of sorts between those with power and those without. But don’t let my intentional ignorance mislead you – my sympathies have always been with the oppressed because that’s how I was brought up – it’s just that a too-detailed analysis of the whys and wherefores of history sometime seem superfluous to the day’s realities. Bullies are a part of life, I’ve assumed, whether they are in the school playground, directing armed forces across the world stage, or slapping high tariffs on poor nations. All I need to know is that I should oppose oppressors, not appease them.

I’m not one to obsess over the historical antecedents of oppression. Perhaps because I take it as a given that civilization’s conflict-ridden unfolding has and always will be a dialectic of sorts between those with power and those without. But don’t let my intentional ignorance mislead you – my sympathies have always been with the oppressed because that’s how I was brought up – it’s just that a too-detailed analysis of the whys and wherefores of history sometime seem superfluous to the day’s realities. Bullies are a part of life, I’ve assumed, whether they are in the school playground, directing armed forces across the world stage, or slapping high tariffs on poor nations. All I need to know is that I should oppose oppressors, not appease them.

That simplistic model suited me fine for a while, that is until my reading and experience began to reveal certain patterns, including history’s masochistic tendency to repeat itself. Over the past year, for instance, I’ve been taking a deeper dive into the history of the Israeli and Palestinian conflict. My most recent plunge was viewing the film Palestine 36, a 2025 historical drama written and directed by Annemarie Jacir. The film recounts the 1936–1939 Arab revolt against British colonial rule in Palestine prior to the formation of the Israeli state in 1948. It is powerful, critically acclaimed, and despite the fact that it is heavily slanted toward the Palestinian viewpoint, historically accurate. (But talk about a short film run! My movie-loving town of Santa Fe had exactly one screening of Palestine 36. Me and my 12 fellow audience members loved it!)

Coincidentally for me, this viewing was followed one day later by a webinar that was sponsored by the New Israel Fund (NIF) that gave a “boots on the ground” account of the current state of Jewish settler violence against Palestinians on the West Bank The West Bank at Boiling Point: Standing Up to Settler Violence • New Israel Fund. In case you’re wondering, the violence is worse now than when I wrote a post-October 7th essay on the intentional destruction of Palestinian crops and human life. That account can be found in my new book The Road to a Hunger-Free America (The Road to a Hunger-Free America: Selected Writings of Mark Winne: Mark Winne: Bloomsbury Academic – Bloomsbury).

Combined, these two exposures present the heartbreaking, gut-wrenching consequences of history-past and present which appears to be continuous river of blood that may be too wide to ever bridge. We’re reminded of the millennia of the world’s Jewry perpetually persecuted and yearning for a homeland. We see Britain, at the helm of its crumbling empire, including Palestine, enabling (The Balfour Declaration – 1917; the Peel Commission – 1936) the early Zionists to begin their “Exodus” into Palestine. We witness Arabs, whose tenacious love of their land is rooted in villages where they have tended the same olive trees and grazed the same pastures for centuries. Later, Britain would aide and abet Jewish settlers in seizing Arab land (today that task is performed by the Israeli Defense Forces) in the same way that the American calvary and federal government protected settlers who were trampling Native American land. Fort Apache-like, the early Jewish settlers built (and continue to build) walled compounds with watchtowers, supposedly to ward off hostile reactions from those whose land they are stealing.

Like their forebears of 90 years ago, today’s illegal Jewish settlements continue to push into the West Bank, destroying Palestinian homes, vehicles, and agricultural fields. The New Israel Fund webinar (11/10/25) painted an updated picture of the surge of settler killing and destruction that the United Nations has characterized as “the worst violence ever.” Providing what they call a “protective presence”, the NIF creates a human shield by courageously placing its staff and volunteers between the Palestinians and hostile Jewish West Bank settlers. The NIF activists include Israeli Jews, Jews from other countries, Palestinians, and non-Jewish supporters. They also support Palestinian resilience by rebuilding homes and replanting olive trees destroyed by rampaging settlers.

Here are some highlights from the webinar’s presenters:

Eid Suleiman Hathaleen (Palestinian) from Umm al-Khair village saw a friend murdered by a settler. IDF tactics now include placing outposts in Palestinian villages and accusing villagers of being members of Hamas as a justification for their harassment. He reported that among the NIF volunteers were two American activists who were deported by the Israeli government.

Ziv Stahl, Director of Yesh Din which is a NIF partner that documents settler violence on the West Bank and provides legal support to Palestinians. He said West Bank settlers want to double their numbers from the current level of about half a million to one million. He said, “hundreds of settlers raid villages destroying chicken coops, cars, and everything. The IDF often accompanies them.” He confirmed that the West Bank is much worse and more violent than it has been.

Rabbi Avi Dabush, a leader of Rabbis for Human Rights, organizes volunteers to plant trees and harvest olives. He said they go into the fields everyday but are becoming more worried about how to protect themselves as well as the Palestinian farmers. He referred to the settlers as “Jewish terrorists who think God is talking to them.” His international group of 50 volunteers were there for 22 days this fall harvesting olives and were attacked by settlers on 3 of those days. To their traditional arsenal of guns, clubs, and machetes, the settlers are now using drones, one of which harmed a female rabbi when it flew into her head. At one point, their group was surrounded by armed settlers who fired their guns in the air. The Rabbi went on to say that “The village’s Palestinian mayor said this happens all the time.”

In addition to providing direct assistance through solidarity with Palestinians, NIF’s Executive Director Daniel Sokatch described how the organization pushes back against the authoritarianism of Prime Minister Netanyahu and his supporters, whom Sokatch labeled the “MAGA Likud.” He summed up NIF’s combined service and policy role by invoking the quote “We comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable.”

NIF’s biggest recipient of financial support is the World Central Kitchen (WCK). Nearly $3 millions of NIF funds are directed at WCK’s work preparing millions of meals for the severely afflicted people of Gaza. Tunde Wockman, one of WCK’s key staff in Gaza, ran down the numbers of what one can only imagine is the most excruciatingly difficult relief mission in recent times. She said that six large WCK kitchens around Gaza have prepared 160 million hot meals since October 7th. Additionally, WCK operates two large mobile bread trucks that bake 60,000 loaves a day; they are serving food in Gazan schools and distributing infant formula in what remains of the territory’s hospitals. But what I found most striking about Ms. Wockman’s report was their attention to the local food system. While they will normally source their food from local sources, that task is impossible in today’s Gaza. But when it comes to the workers, it’s a different story. “We make local people the architects of their own relief,” she said. In Gaza, WCK does not utilize well-intentioned volunteers from first world countries; they train and use over 1,000 Palestinians to prepare and distribute food to their own starving people.

So much hate and heartache have ground humanity down over the centuries, that it’s not surprising we feel compelled to celebrate the birth of Jesus in Bethlehem and Hanukkah’s triumph of light over darkness. Without the star and the candle, we’d be consumed by the darkness that threatens to crowd hope from our hearts. The long-running pain that is Palestine made me think of a few lines from Bruce Springsteen: “On the plains of Jordan/I cut my bow from the wood/Of this tree of evil/Of this tree of good.” We are all that one tree whose roots may at times be watered by the bloodlust of a thousand years. But it may also find nourishment from the good works of the likes of the New Israel Fund, Yesh Din, the World Central Kitchen, and many others whose yearning for the light may yet drown the darkness. That’s where I’m putting my money; I hope you might do the same.

November 23, 2025

Of Microbes, Capitalism, and Christmas Shopping

Trump’s Pro-Hunger Agenda

Andy Fisher, author of Big Hunger: The Unholy Alliance Between Corporations and Anti-Hunger  Groups (MIT Press, 2017), always has an unorthodox take on the days’ events. As we’ve watched the whole Trump-initiated food stamp debacle unfold – leaving 42 million of America’s most vulnerable people in a heightened state of food insecurity – it’s natural to take sides and simplify the problem. We see a cruel President use political leverage against Democrats by withholding Congressionally approved funds to feed SNAP recipients during the government shutdown; we see Democrats, emergency food providers, and just about every other sentient being scream at him for starving the poor. But behind what is certainly a black and white/good versus evil clash is also a more nuanced explanation of how our hard driving, take no prisoners economic system tolerates a level of desperation that necessitates the nation’s SNAP program. That’s why I’ve come to enjoy Mr. Fisher’s work over the years. He looks past the easy assumptions and takes on the underlying systemic causes and failures of the American economic behemoth. Give his new article a thoughtful read. You’re likely to see things a little bit differently. Read it here: Trump’s Pro-Hunger Agenda and the Cruel Logic of Capitalism | The MIT Press Reader

Groups (MIT Press, 2017), always has an unorthodox take on the days’ events. As we’ve watched the whole Trump-initiated food stamp debacle unfold – leaving 42 million of America’s most vulnerable people in a heightened state of food insecurity – it’s natural to take sides and simplify the problem. We see a cruel President use political leverage against Democrats by withholding Congressionally approved funds to feed SNAP recipients during the government shutdown; we see Democrats, emergency food providers, and just about every other sentient being scream at him for starving the poor. But behind what is certainly a black and white/good versus evil clash is also a more nuanced explanation of how our hard driving, take no prisoners economic system tolerates a level of desperation that necessitates the nation’s SNAP program. That’s why I’ve come to enjoy Mr. Fisher’s work over the years. He looks past the easy assumptions and takes on the underlying systemic causes and failures of the American economic behemoth. Give his new article a thoughtful read. You’re likely to see things a little bit differently. Read it here: Trump’s Pro-Hunger Agenda and the Cruel Logic of Capitalism | The MIT Press Reader

Save 30% on My New Book!

If you are reading this blog on the day it’s posted (11/24), I should warn you that you only have 31 shopping days left until Christmas! Does that realization send a hot bolt of fear through your internal organs? Do you feel a smothering blanket of anxiety descend on you? Worry no more; The Road to a Hunger-Free America: Selected Writings of Mark Winne is now available directly from the publisher at 30% off the list price. After all, nothing says “you are a special person in my life” like the gift of good literature. Even if holiday shopping isn’t worrisome, and you’ve been meaning to buy a copy all along, you’re in luck! The sale was just announced, so this is one of those times when procrastination pays off. But don’t delay any further! This offer is only available until December 7th. Here’s the link to low-cost enlightenment: https://www.bloomsbury.com/us/9798765132340

If you are reading this blog on the day it’s posted (11/24), I should warn you that you only have 31 shopping days left until Christmas! Does that realization send a hot bolt of fear through your internal organs? Do you feel a smothering blanket of anxiety descend on you? Worry no more; The Road to a Hunger-Free America: Selected Writings of Mark Winne is now available directly from the publisher at 30% off the list price. After all, nothing says “you are a special person in my life” like the gift of good literature. Even if holiday shopping isn’t worrisome, and you’ve been meaning to buy a copy all along, you’re in luck! The sale was just announced, so this is one of those times when procrastination pays off. But don’t delay any further! This offer is only available until December 7th. Here’s the link to low-cost enlightenment: https://www.bloomsbury.com/us/9798765132340

All Creatures Small and Smaller

I can remember becoming an enthusiastic amateur soil scientist in my late 20s.  My interest was spurred by an effort to dramatically expand the number of community gardens where I was working in Hartford, Connecticut. Given the abysmal selection of decent, even safe growing spaces among some rather terrifying-looking vacant lots, we had to draw on a special biological alchemy to create semi-natural mediums capable of producing edible crops. With diligent research, neighborhood sweat equity, and hundreds of cubic yards of composted leaf mulch, we finally succeeded in creating enough “growable” space for a couple of hundred families.

My interest was spurred by an effort to dramatically expand the number of community gardens where I was working in Hartford, Connecticut. Given the abysmal selection of decent, even safe growing spaces among some rather terrifying-looking vacant lots, we had to draw on a special biological alchemy to create semi-natural mediums capable of producing edible crops. With diligent research, neighborhood sweat equity, and hundreds of cubic yards of composted leaf mulch, we finally succeeded in creating enough “growable” space for a couple of hundred families.

As my personal interest in gardening grew over the years – I’ve counted 15 community and backyard gardens in my lifetime start-up list – so has my love for soil. The sensual high point of every gardening year takes place in early spring when I plunge my hands into a garden bed and cradle a cool, crumbly bowl. Inhaling it deeply, I now have enough years under my belt that I can tell, with some accuracy, what ingredients are in the mix and what’s missing. While a few books, articles, and pamphlets have educated my olfactory faculties along the way, I still know there’s a pretty big gap between what I know and don’t know about the life of that soil. Thanks to a lovely, little book called What if Soil Microbes Mattered – Our Health Depends on Them, my knowledge gap has not only closed, but it has also become enlivened by an awareness of a life I cannot see.

Written by a former colleague of mine at the Johns Hopkins University Center for a Livable Future, Leo Horrigan, Microbes takes us on an underground tour of fungus, bacteria, and a “microscopic universe that is essential to plant health.” Not only is most of this life-giving activity out of sight, even when we turn the soil over with a spading fork, it’s also a busy subsurface city where millions of invisible particles move to and froe. (Get it for free: a PDF version of the book here and an audio version here.)

So, what’s the matter with the matter? Mr. Horrigan tells us that it has been estimated that between 30 and 50 percent of our soil’s carbon has been lost due to agriculture with most of it ending up in the atmosphere. “The Chemical Age of Agriculture has greatly harmed soil microbes—and therefore soil ecosystems. This damage has had a cascading effect on farms…and rural communities…. If agriculture became attuned to the needs and functions of soil microbes, this would open enormous possibilities for improved agronomic, ecologic and economic outcomes.”

Another way to put it: If we don’t learn to respect our dirt, we’re going to be in a world of hurt.

Befitting its tiny subjects, Microbes is a slim, some might say petite volume of 97 pages. Without sacrificing the science or the depth of its research (32 of those pages are citations), Mr. Horrigan presents a necessarily complex subject in a readable and accessible fashion. From fresh-faced high schoolers to decomposing gardeners like me, What If Microbes Mattered? will make us all better-informed stewards of the earth.

November 11, 2025

Food Takes Center Stage in 2025 Election

I’ve always been fascinated by how and what city mayors eat. One of my early favorites was the now-deceased mayor of Hartford and retired firefighter, Mike Peters. As a man of considerable rotundity, he had elevated the usual hot-dog chomping American mayoral image to a more refined version of “hizzoner” holding court at the city’s best steakhouse. Knowing his gustatory habits, I would occasionally stop by in hopes of turning his love for food into a food policy moment. But mixing his pleasure with business required more delicacy than I had yet mustered at that early point in my career. While I can point to a minor success or two – an amuse-bouche, as it were – pairing the plight of Hartford’s hungry children with the mayor’s favorite cabernet was a poor choice.

Fast forward 30 years to November 4, 2025, and we can see that food and food policy are no longer political after thoughts. The recent election of Zohran Mamdani as mayor of New York City was preceded by a New York Times headline that read, “Mamdani built a campaign around food.” It included a quote from Grant Davis Reeher, a political science professor at Syracuse University, who noted that Mr. Mamdani had the exceptional ability to reference food at “the personal level and the policy level.” You can see how that fusion plays out when the mayor-to-be enjoys a chicken biryani with worshipful gusto at the open-all-night Kabab King, then makes a brilliant video to illustrate how the price of a chicken hallah dish can be reduced by modifying government’s regulatory burden on street vendors.

It made me wonder if Mayor Mamdani had read my new book The Road to a Hunger Free America** that includes an essay on Paterson, New Jersey and its mayor of Arab American heritage, Andres Sayegh. As mayor, Sayegh has been a tireless promoter of everything Paterson, including its outstanding Palestinian restaurants. His caloric energy was fuel for the city’s website that’s titled “Paterson: Great Falls, Great Food, Great Future,” one of the few city taglines I’ve seen that put food forward. This promotional flourish extends to several tangible city initiatives designed to solve Paterson’s numerous food access and affordability problems. In Mamdani’s case, it’s his campaign proposal to develop city-managed supermarkets in each of New York’s five boroughs that has grabbed public attention. Regardless of which side of the Hudson River you find yourself on, the message coming from elected officials is that we should joyfully celebrate the wonders of our respective urban cuisines. At the same time, city halls must deploy innovative policies to promote robust food economies and greater food security.

Colorado Goes Big on School Meals

With less national fanfare than the Big Apple, two Colorado ballot measures succeeded in putting more apples into the little hands of school children. By wide margins, the state’s voters approved Proposition LL which will allow school meal programs to keep $12 million of additional tax money to fund Healthy School Meals for All, a measure that Colorado voters passed in 2022. But even more significant was the passage of Proposition MM, especially if you’re interested in the commitment of taxpayers to childhood nutrition. MM (not M&Ms) will lower state tax deductions on income earners over $300,000 per year. This will add approximately $95 million per year to Colorado’s school food service budgets. In other words, nearly 60 percent of the state’s voters chose taxing the rich rather than eating the rich to continue Colorado’s reputation as the healthiest state in the country.

As one who admittedly finds pleasure in analyzing voting patterns at very local levels, I couldn’t help but notice that all of eastern Colorado voted overwhelmingly against both LL and MM. Yes, this is a traditionally conservative area made up of small towns, ranchers, and farmers. But they have children too, and by all accounts they want them to be as well-nourished as the kids in Denver and Boulder. Then it occurred to me that this same region constitutes much of Congressional District 4 which is represented by the notorious half-wit, Lauren Boebert. Among a long list of flaws, foibles, and failures, Boebert recently donned a racist Halloween costume that belittled and degraded Latinos. Now that Congresswoman Marjorie Taylor Greene seems to be having a Come-to-Jesus moment, Ms. Boebert has officially become the House of Representative’s Head Lunatic in Residence. It’s my considered opinion that with intelligent and responsible political leadership, the people of CO CD-4 will one day rekindle their innate compassion to support public efforts to bring the best food possible to all Colorado children.

SNAP

Of course, these local and statewide November 4th elections took place against the striking backdrop of a suspended SNAP program. To quote Federal District Court Judge John McConnell’s ruling that rebuked the Administration’s denial of emergency SNAP fund use, “This should never happen in America.” But it has and it did. Forty-two million Americans are now juggling their rent, food, and car money to see how to stretch their already slim budgets to accommodate the absence of SNAP benefits.

What kind of cojones does it take for Trump to resist a direct order from the American judiciary to feed the country’s most vulnerable people with emergency funds ($5 to $6 billion) that have been appropriated by Congress as well as other available funds within Section 32 (many billions of dollars). And the next headline of note, juxtaposed with the dire SNAP news, was the announcement that Elon Musk will receive a payment of one trillion dollars for God knows what. This is an amount that is capable of funding the entire food stamp program for the next ten years! In deference to my late mother who has scolded me for using the “f” word when expressing my disgust with such yawning injustices as this one, allow me to say that this is totally copulated up!

A Thousand Points of Light Across the Nation; One Burned Out Bulb in Washington

Fortunately for those who are victims of Trumpism, American community morality belies the saying that “Leaders are only as good as the people who follow them.” The people across America are far better; they are rising to the occasion by taking care of their own, while the President gags on his own venom and lavishes attention on himself. Supermarket customers are adding $5 to their tab at the check-out counter for the local food bank, food and cash donations are flowing into food pantries, pop-up food sites are showing up in bookstores, and late-night TV celebrities are setting up food donation and giveaway stations in their studio’s parking lots.

With less fanfare, food policy councils, United Ways, and other community-based service institutions are coordinating and supporting the work of numerous emergency food sites. They are also using data and their collective knowledge of the community to spotlight groups of greatest need. For instance, I’ve followed the work of the Knoxville (Tenn.) Food Policy Council over the last several months. Not only are their members gathering information about the region’s food needs and disseminating lists of resources to the wider community, but the council has also identified unique pockets of community hardship. These are about 250 people “including refugees, parolees, and asylees [who] will no longer have access to these [SNAP] benefits when the government re-opens, and SNAP is re-established.” In an additional turn of the screw, Trump’s Neanderthals have excluded categories of people, typically the most vulnerable, from receiving food assistance.

As big-hearted and motivated by an enormous charitable impulse as these private local endeavors are, remember that public food assistance out spends its private sector brethren by a ratio of 9 to 1. Food banks, etc. can never rebuild the dam, they can only plug the leaks. Most of them know that, but with enormous courage they have not retreated from shoring up the dam that threatens to burst and drown them.

What, if any, morality guides the leadership of this nation? A snake pit of unprecedented greed and servile self-interest writhes down White House corridors tarnished by the dirt of its own occupants. It will take several terms of new and decent administrations to purge “the people’s house” of the stink and filth now permeating its hallowed halls. But as a practical and political matter, we can build food policy platforms – both locally and nationally – based on access to healthy and affordable food. Trump says grocery prices are “way down.” He lies. CNN says grocery prices were up 2.7 percent in September. An NBC poll found that only 30 percent of voters believe Trump has lived up to their expectations that he would reduce inflation.

Policy actions like those proposed by Mamdani in New York City, expanding school nutrition initiatives like those underway in Colorado, and hyper-vigilance like you find in the caring community of Knoxville are the tickets we need to ride the train to food security. But we must also invite all to ascend a higher moral ground and take back a federal government quickly eroding under Republican control. As New York’s Mayor-elect said in his victory speech: “Fingers bruised from lifting boxes on the warehouse floor, palms calloused from delivery bike handlebars, knuckles scarred with kitchen burns: These are not hands that have been allowed to hold power.” And how often have we ignored the world’s greatest invitation to safety and freedom that New Jersey’s Governor-elect, Mikie Sherrill’s victory speech echoed from the Statue of Liberty located only a few miles away: “Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free.” Food security, dietary health, and food as an economic engine are not only important messages, they have also become the medium as well. Whether you’re discussing the price of eggs, the regulation of food trucks, immigrants working in restaurant kitchens, termination of the food stamp program, school meals, or retail food stores, food issues are not only a poignant reminder of America’s social and economic injustices; they are now vehicles for illustrating larger problems and the opportunities for a better American life.

** My new book “The Road to a Hunger-Free America — Selected Writings of Mark Winne” is available at a 20% discount if you buy it online directly from the publisher at bloomsbury.com/9798765132340. Use discount code GLRBD8.

October 29, 2025

Hunger is a “Sensitive Social Issue”

On October 28, I attempted to “boost” my recent Facebook post that promoted my new book The Road to a Hunger-Free America (that post is replicated here). For those not familiar with Facebook (a form of ignorance I would heartily endorse), the boost function places your post before a much wider audience of viewers than most people would have as mere Facebook “friends.” A small fee and a short review process are required for Facebook to approve your boost. Within five minutes of submitting my request, I received a rejection notice with a boilerplate explanation that contained the following sentence:

My new book “The Road to a Hunger-Free America — Selected Writings of Mark Winne” is available at a 20% discount from bloomsbury.com/9798765132340 with discount code GLRBD8. L to R: Paterson Mayor Andre Sayegh, Mark Winne, and Shana Mandradge.

“Your ad may have been rejected because it mentions politicians or is about sensitive social issues that could influence public opinion, how people vote and may impact the outcome of an election or pending legislation.”

I was given an opportunity to appeal their decision, which I did noting that yes, hunger is a “sensitive social issue” but not one I was taking a position on in my post. And even though the Mayor of Paterson, NJ appeared in the photo, there was no explicit or implicit attempt to support him or influence public opinion (he’s not even running for office). God-forbid that one might publicly suggest that hunger is not a desirable state of affairs, or that the chief elected official of a lower income city might be concerned about the food security of his citizens. But other than “Hunger” being in the book’s title, no clever, thinly disguised behavioral modification tricks were employed by the manipulative mastermind, Mark Winne.

Facebook’s AI Appeals Robot rendered a verdict in less time than it takes a hungry man to eat a cheese sandwich: “Appeal denied.” It then had the chutzpah to ask me if I was satisfied with the process and provided a little box in which to write a comment. Boiling over, I probably didn’t help my case by writing an expletive-laced comment describing how the CEOs of Meta/Facebook and the United States of America were probably in cahoots with each other. After all, keeping the lid on anything that speaks of dissent is clearly in the self-interests of those who have no need for democracy.

Given that 42 million Americans are staring into the abyss of a pretty lean November, it would be of little surprise that Trump, Zuckerberg, and their cronies are motivated to downplay or distract Americans from Republican efforts to inflict as much pain as possible on SNAP recipients. Refusal by this Administration to take care of the Nation’s most vulnerable–-the majority of SNAP recipients being elderly, children, and disabled—and callously shift the burden of nourishing the needy to the already over-burdened food banking community reaches new heights of unconscionability.

If Facebook is willing to squelch a benign attempt by a lowly author to sell a book about hunger, what lengths will it go to undermine the rising tide of discontent with a President who is corrupt, despotic, and immune to the sufferings of his own people.

October 8, 2025

The Road to a Hunger-Free America is Here!

I am proud to announce the publication of my fifth book The Road to a Hunger-Free America: Selected Writings of Mark Winne (Bloomsbury). This announcement is likely to provoke a follow-up question which is why write another book at the age of 75? One answer might be that writing is a better game for me to pursue than either golf or pickle-ball. Another response comes in the form of a diagnosis suggested by Juvenal’s quote, “Many suffer from the incurable disease of writing….” But then there is the less than humble thought — offered from the heart as much from the mind — that I still have something to say that deserves to be heard.

I am proud to announce the publication of my fifth book The Road to a Hunger-Free America: Selected Writings of Mark Winne (Bloomsbury). This announcement is likely to provoke a follow-up question which is why write another book at the age of 75? One answer might be that writing is a better game for me to pursue than either golf or pickle-ball. Another response comes in the form of a diagnosis suggested by Juvenal’s quote, “Many suffer from the incurable disease of writing….” But then there is the less than humble thought — offered from the heart as much from the mind — that I still have something to say that deserves to be heard.

And what I have to say is what I’ve learned over the course of 56 years as a food activist and writer. If we are to end the scourge of hunger in the U.S., in other words, advance a just and sustainable food system, such an effort demands an eagle eye on people, places, and actions. Further, and within those three groupings, I have discovered that success is keenly related to a fundamental application of justice, an active imagination, a clarity of focus on needs and solutions, and effective leadership. What I mean by all this is made visible by the stories and analyses found in these selected essays gleaned from nearly 20 years of writing.

Get it Cheaper, Get it SoonerBuy The Road to a Hunger-Free America directly from the publisher, Bloomsbury, and save 20%. Go to The Road to a Hunger-Free America: Selected Writings of Mark Winne: Mark Winne: Bloomsbury Academic – Bloomsbury and use the discount code GLRBD8, and you’ll be on your way to owning a classy piece of literature!

AppearancesWant it even cheaper and faster? Come to Rutgers University in New Brunswick, New Jersey on October 15 and buy the book, at some ridiculously low price, between 11:30 and 1:30. Since I’ll be there in person, you’ll get the added bonus of a signed copy. I’ll be in the Institute for Food and Nutrition and Health building on the Cook College campus at 61 Dudley Road, New Brunswick, New Jersey (parking is nearby and fairly easy). Besides saying hello and buying a book, you’ll have a chance to enjoy this beautiful, state-of-the-art “green” building complete with a 3-story “living wall” alive with 5200 plants, and the delicious and hopelessly healthy Harvest Café.

Can’t make it to Rutgers? Then go to Paterson, New Jersey on October 16, World Food Day, where I’ll be hanging out at A Better Market while yakking, selling, and signing. The market is the inspiration of Shana Manradge, a community activist who is featured in the book. Word has it that Paterson’s mayor is going to stop by so that he can have his photo taken with me! I’ll be there from 12 until 3, and the market is located at 215 Rosa Parks Blvd in Paterson, which by the way, is one of the east coast’s great historic cities.

EndorsementsI’m deeply grateful for the words of my book’s endorsers. Not only are they often touching, but their comments also illuminate my purpose and identify the most appropriate audience. Tricia Jenkins, Assistant Professor of Urban Food Systems at Kansas State University, said, “This collection provides a more nuanced account of alternative food movements and food justice than any lecture, peer-reviewed publication, or textbook chapter I could offer to my students.”

Cathy Stanton, Teaching Professor at Tufts University, wrote “Mark Winne’s latest book is grounded in theory and tested in practice to present a clear framework against American food injustice.”

And Christopher Bosso, Professor of Public Policy and Political Science at Northeastern University made me feel really old when he said, “Mark Winne is a legend in the food movement, and his insights are particularly relevant today.”

Who am I to argue with these Professors! It never got me anywhere when I was in college!

But just as important as the words of academics are the words of the people you’ll read about in The Road to a Hunger-Free America. When Jo Argabright in Kansas says, “I’m tired of watching my town die,” or Maria Alonso in California says, “This is my community, and I hear from the gardeners all the time how the ‘garden makes me feel better,’” I hear two women giving voice to their passions, and just as importantly, the needs of others in their respective communities. Leaders like Gabe Pena in West Virginia describe how to bring economic vitality back to ex-coal mining towns through food and farming, and Dr. Namali Fernando in Virginia recounts her extraordinary efforts to refocus the practice of pediatrics on nutrition and dietary health.

From the other end of the country, you’ll read about the Herculean efforts of a food bank to stem the tide of hunger in Seattle, and then how the quiet university town of Missoula, Montana made food and farming a ubiquitous part of their community. The list goes on and touches on examples from all over the country. But these aren’t just news stories you’d find in your daily newspaper. They and the book offer an analysis set against a backdrop of social justice theory and a history of good practice. Together, they contain lessons for anyone interested in really ending hunger.

Anyone who knows me knows that I love writing stories about people, places, and actions that are changing the food system for the good. But as enamored as I am by their details, I’m equally passionate about passing them through the sieve of theory and my own decades of experience. In this selection of essays, complemented by some of the great thinkers of our time, I’ve tried to give you the best of both worlds.

September 28, 2025

The Hungry Don’t Count

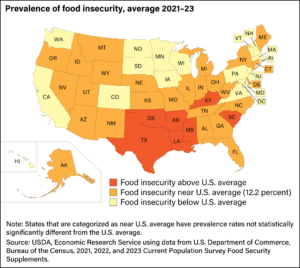

The Trump dictatorship announced yet another effort to conceal information from the American public. Herr/Hair Trump’s USDA will terminate the annual measurement of the prevalence of food insecurity (hunger) in the United States. Vital research data that has been used for over 30 years to guide the actions of food activists, advocates, policy makers, and the general public will be “disappeared” by the Orange Man’s Gestapo. In the best tradition of dictators throughout history — Mao denied the death of millions by famine in the early 1960s; Hitler hid death camps from the eyes of so-called “good Germans;” Stalin banished discussion of the Soviet Ukraine famine that killed upwards of 10 million Ukrainians — American citizens who suffer from a lack of adequate nourishment will no longer be counted.

from the American public. Herr/Hair Trump’s USDA will terminate the annual measurement of the prevalence of food insecurity (hunger) in the United States. Vital research data that has been used for over 30 years to guide the actions of food activists, advocates, policy makers, and the general public will be “disappeared” by the Orange Man’s Gestapo. In the best tradition of dictators throughout history — Mao denied the death of millions by famine in the early 1960s; Hitler hid death camps from the eyes of so-called “good Germans;” Stalin banished discussion of the Soviet Ukraine famine that killed upwards of 10 million Ukrainians — American citizens who suffer from a lack of adequate nourishment will no longer be counted.

Why does this matter? First off, the survey found over 47 million Americans, or 13.5 percent of the country, were food insecure in 2023 with a subset of 5.1 million experiencing very low food security. This is reason enough to pay attention to and work for national policies, like the SNAP program to mitigate these conditions.

But at the local and state levels, this annual data is critical to both motivating and focusing the work of activists and policy makers. For instance, my food work in Hartford, Connecticut overlapped with a period in the late 1980s and early 1990s when researchers from the Food Research Action Center (FRAC), Cornell, and Yale were developing these measurement tools and survey methods. They were not just trying to give credence to anecdotal claims that hunger existed in America, they also wanted to know which demographic groups were at greatest risk and what conditions existed at a household level that contributed to food insecurity. Indeed, the term food insecurity, in use for many years in the international arena, was generally unused in America. Hence, the vague and somewhat misleading word “hunger” served to cover all manner of food and nutrition deficiencies—a lack of refinement and specificity that only served to undermine efforts by those who wanted to carefully target necessary resources.

Once the tools were assembled in the laboratories of talented social scientists, they were field-tested in real places of known poverty. Using the title “Community Child Hunger Identification Project” (CCHIP)—the model for the U.S. Household Food Security Module—the survey was piloted in New Haven, Connecticut and later in Hartford. The results in Hartford were staggering and seized the front page of the Hartford Courant the day after the report’s findings were released. Over 76 percent of the city’s lower income children were identified as food insecure according to the study’s measures. Hartford’s mayor immediately responded with shock and a resolve to do something about it. Among other things, the resulting Mayor’s Task Force on Hunger recommended the creation of the Hartford Advisory Commission on Food Policy, now the nation’s second continuously operating food policy council

The political impact of the annual food security report is often bi-embarrassing. Regardless of which party is in power, it has evoked both shame and pride based on the annual results. If the number of hungry people goes up one year, the party in power has some explaining to do and hopefully some action to take. If the number goes down, the sitting President and his Secretary of Agriculture will puff up their chests and strut their stuff.

But one of the most valuable and often disheartening features of the annual survey is the state rankings. Depending on where I was living and working at the time, I would immediately turn to the report’s appendix where an alphabetical list of states included their respective food insecurity percentages as well as their percentage of “very low food security” people. Perhaps because the USDA staff who performed the analysis didn’t want to embarrass certain states, the list was not really a ranking—you had to “rank” yourself by picking your state and then tabulating who was higher and lower. Call me weird, but I can remember pouring through the data and lists with as much fervor as a baseball enthusiast parses major league standings.

While in Connecticut, food advocates were shocked in the 1990s by how high our food insecurity levels were—largely a result of high poverty rates in the state’s cities. A concerted effort by state government and non-profit groups, spurred in part by these humiliating numbers (ironically, Connecticut as a whole had the highest per capita income in the nation), significantly reduced the state’s prevalence of food insecurity as the 21st century dawned. Similarly, when I moved to New Mexico in 2004, the annual USDA presentations of the nation’s food insecurity rates revealed that we toggled back and forth with Mississippi for the dubious distinction of being the hungriest state in the nation (more than one wag suggested that the “Land of Enchantment” slogan on our license plate be changed to the “Land of Hunger”).

But everyone recognized that the abysmal state of New Mexico’s food security was no laughing matter, including then governor, Bill Richardson. Following the 2003 release of food security survey which listed New Mexico as the most food insecure state in the nation, Richardson appointed a task force to make recommendations and even implement solutions to reduce the level of food insecurity. Progress was slow, political leadership was anemic, and the task force’s members grew frustrated. But over time, and through several iterations of organizational engagement from both the private and public sectors, New Mexico made significant progress rising from the absolute bottom to somewhere in the middle nationwide.

The value of measurement is that it is part of a feedback loop that tells us what’s working and what’s not. It also tells us who’s hurting and motivates us to reduce that pain. One problem with Trump that infuses his politics is that he doesn’t care who’s hurting. “The still, sad music of humanity”, pain, suffering, ill health, and hunger do not fall within his domain of interest or concern. In the “hangry” tone of one who missed breakfast that morning, USDA’s ejaculatory announcement on September 20th said “These redundant, costly, politicized, and extraneous studies do nothing more than fear monger. For 30 years, this study [sic]—initially created by the Clinton administration as a means to support the increase of SNAP eligibility and benefit allotments—failed to present anything more than subjective, liberal fodder….” Dictatorships cleanse the media of any adverse news, scrub scientific research of any opposing data, and treat the reverent accumulation of human knowledge as nothing more than a waste can that needs to be emptied regularly. The goal is to leave the people blissfully ignorant; their minds becoming nothing more than a blank slate to be etched on by the tyrant.

I have known many of the people both in and out of government over the years who have developed, implemented, and refined the measurement of food insecurity in the U.S. They are gentle, highly intelligent souls whose only wishes are to uphold the highest standards of their profession and place their talents in service to the cause of reducing human suffering. Their impact with regard to the annual food security study, in collaboration with a myriad of local and state advocates, has been immense. My examples from Connecticut and New Mexico are only two of thousands from across the country where determined individuals, eager for information, have leaned on these annual studies to fight a condition that should never, ever exist in this country.

Dictators depend on a passive citizenry. Unless we act now, Trump’s lies and low regard for the human condition will metastasize further, and in the case of food security, make our country a hungrier place. Please be in touch with your Members of Congress and let them know that you are opposed to the elimination of the U.S. Food Security Report. The Food Research Action Center (FRAC) has made that easy to do. Please go to this link ACTION NEEDED: Tell Congress to Reinstate USDA’s Food Security Report and share your beliefs with your federal officials. If you are part of a food bank, food pantry, or other organization with many volunteers and supporters, share this post and the FRAC link with them. Don’t let the tyrant have the day!

August 4, 2025

The Famine Next Time

I’ve turned my attention lately to the subject of famine. Not a cheery topic I know,  but one that, like the proverbial Doomsday Clock ticking down to midnight Armageddon, seems more real than metaphorical. What prompted this grim look into the future was a deep dive into the past that included a reading of Rot: An Imperial History of the Irish Famine (Hachette Book Group, 2025) by Padraic X. Scanlan. I only had to get to page three before I was reminded that the starvation of one million of my ancestors and the forced emigration of another one and a half million between 1845 and 1851 were less the potato’s fault than the oppressive regime of Britain’s Irish colonial rule.

but one that, like the proverbial Doomsday Clock ticking down to midnight Armageddon, seems more real than metaphorical. What prompted this grim look into the future was a deep dive into the past that included a reading of Rot: An Imperial History of the Irish Famine (Hachette Book Group, 2025) by Padraic X. Scanlan. I only had to get to page three before I was reminded that the starvation of one million of my ancestors and the forced emigration of another one and a half million between 1845 and 1851 were less the potato’s fault than the oppressive regime of Britain’s Irish colonial rule.

My reading of Scanlan also coincided with a recent lecture I attended by Dr. Kyle Harper, a history professor at the University of Oklahoma. The thrust of Dr. Harper’s presentation was a seat-squirming comparison between the fall of the Roman empire and today’s world roasting and drowning from climate change. Add in current events like Israel’s attempt to starve the Gazans from their own land, and the maniacally undemocratic, anti-science perspective of the Trump Junta, I found myself pushing the hands of the Doomsday timepiece several seconds closer to oblivion.

Three years ago, I was staring out the window of one of those cushy-seated tour buses at the oh-so green western Ireland countryside. I noticed that there were stonewalls running straight up the face of passing hills. Every agricultural wall or fence I’ve ever seen also stretched horizontally across a slope to enclose livestock in neat rectangular paddocks. These vertical walls, however, ended a couple of hundred feet short of the summit, un-intersected by a horizontal barrier, allowing even the stupidest of sheep to find their way around them. As if sensing my confusion, our bus driver, whose knowledge of local history far exceeded the skill required to maneuver a bus down narrow country lanes, informed us that these weird stonewalls were the result of make-work projects designed by British landlords. Irish people in the 1840s, with one foot in the grave from hunger, were paid a pittance to build these walls to nowhere. What they earned bought them enough food to barely stay alive.

The Delaney and Lawlor sides of my family can be forgiven for not saluting the Union Jack. The horrors of rotting potatoes and the pitiful relief efforts that—as Scanlan lays out in gut-churning detail—followed free market principles and the denigration of the Irish people. This left them gaunt, fleeing for Australia and North America, or moldering in a shallow Kilkenny grave. But their unnecessary sacrifice offers similar lessons learned by ancient Romans, British-ruled Indians, 30 million-plus Chinese who perished from hunger under Chairman Mao, and today’s Gazans wasting away under apparent genocidal intent in a region surrounded by ample food abundance and relief workers willing to risk their lives.

The lesson is one that has repeated itself time and again over two millennia, and was best articulated by the Nobel economist, Amartya Sen: “no famine has ever taken place in the history of the world in a functioning democracy.” That statement has been supplemented over time by Sen and others to include the need for a free press, opposition parties, and non-authoritarian leaders. Sen noted that “What makes a famine such a political disaster for a ruling government is the reach of public reasoning…to protest and shout about the ‘uncaring’ government (The Idea of Justice; 2009).”

For example, assuming Israel remains a functioning democracy, at least when its blood-thirsty, right-wing zealots leave the room, its people, clinging to remnants of a diverse free press and opposition parties, and pressured externally by a rising tide of disparaging global opinion and internally by their innate moral sense, may yet save Gazans from mass starvation and find a peaceful solution to their longstanding conflict with Palestinians.

Scanlan’s Rot is a deeply researched look at one of history’s better known and much studied famines. Phytophthora infestans (p. infestans) originated in Mexico and was imported into the British Isles where it found a hospitable ecosystem in Ireland. Facilitated in the 1840s by global trade—a pre-cursor of sorts to today’s accelerated movement of pathogens around the world—p. infestans turned potatoes to mush. While modern agricultural science would have found work arounds, Ireland was harnessed to Britain’s colonialist yoke which included a slavish adherence to capitalism and the market. Ireland’s many impoverished small landholders and shareholders were monocropping potatoes, often only one variety, partly because it was a nutritious food that’s easy to grow and store, but largely because Britain’s economic structure dominated imports, prices, exports, and crop selection. When p. infestans struck with a sickly vengeance, the system couldn’t bend to find alternative solutions, and catastrophe followed. As Scanlan puts it, “When there is no escape from the market, it eats the weakest first.”

While Ireland’s fields were infected with blight, British relief efforts were infected with a deeply prejudicial attitude toward the Irish and a moral economic fever that guided their relief efforts. The blight, a natural disaster, did not have to be a death knell. According to Scanlan, it was British “colonialism and capitalism [that] created conditions that turned blight into famine…. There was always enough food; the obstacle was a stubborn insistence that private merchants deliver food to the hungry; and that the hungry pay for it with money or labour.” Hence, those walls to nowhere.

Echoing Britain’s profound faith in the righteousness of their economic system, no less a statesman than Edmund Burke admonished against “breaking the laws of commerce, which are the laws of nature, and, consequently the laws of God.“ It was an article of faith among the British elite that overly generous food relief was a moral hazard for the Irish, even though it would have saved hundreds of thousands of lives and surely dampened the Irish diaspora. In short, without being forced to work or pay for food, the Irish, thought by much of the British leadership to be dissolute, would be firmly set on the road to perdition. As Scanlan sees it, “…the Irish poor needed relief from the market, not relief through the market.”

Let me turn for a moment to the present-day Republican Congress for a contemporary American expression of British famine morality. The Republican members and their sanctimonious leader, Speaker Johnson, controlled by a President, who unlike Burke, couldn’t have a credible conversation with God if his life depended on it, have recently imposed work requirements on SNAP and Medicaid recipients, and hollowed out the federal public health and research infrastructure as well as our disaster response capacity. Should another version of p. infestans (bird flu?) or COVID-19 strike, and it will; should climate change cook or cool the crops to perilously diminish their yield as they have and will, our current government will have neither the tools nor resources to assist our struggling people.

Not only has America returned to a mean-spirited form of 19th century British conservatism, subjecting everyone, including the most vulnerable, to the whims of a highly competitive marketplace, it has, even more disturbingly, reverted to a parsimonious, even racist approach to social welfare characteristic of the latter half of the American 20th century. It was then, in the 1960s, at the birth of the food stamp program, that Congress made the poor pay for their food stamps. The so-called “cash purchase” requirement was eventually phased out, but its roots remained, firmly anchored in racist assumptions that Black people could not be trusted with some form of unrestricted cash welfare; hence food stamps and not “basic human need” stamps. Even then, after grudgingly accepting that starvation just wasn’t tenable, elected U.S. officials ensured that the quantity of food stamps granted to any household was never sufficient for an adequate diet. Add in various attempts to impose cumbersome work requirements on food stamp recipients, we have a 21st century U.S. Congress acting toward the nation’s most vulnerable citizens like a 19th-century British Parliament acted toward the hungry Irish.

What also rises to the top in the review of famine’s larger history is Sen’s codicil to democracy=no famine postulate, is the need for a free press, opposition parties, and non-authoritarian leaders. Free press is a stand in for the lack of information about the risk of hunger in any given region, which, if known by public officials, relief organizations, and the general citizenry would provoke a response sufficient to prevent or at least mitigate a pending famine.

Sen (The Idea of Justice) provides an example in the form of India’s last famine which occurred in 1943 near the end of the British Raj (Scanlan provides several examples of additional famines throughout the 19th and early 20th century when India was under British rule). Food shortages in the State of Bengal, caused in large part by their crops being siphoned off to feed the British army’s Asian war campaigns, were responsible for a growing number of starvation deaths. A British-imposed reporting ban had silenced the press, even as Bengalese were dying at the rate of 26,000 people per week. These state of affairs were known by British officials in India, but several months elapsed before a full-scale relief effort was launched (there was no Indian parliament made up of elected Indians to hold the British colonial government accountable). As Sen tells the story, it wasn’t until Ian Stephens, the editor of the British-owned, Calcutta newspaper The Statesman ignored government censorship and ran the news of the growing Bengal disaster. At that point, it was too late for the 678,000 who died over six months of famine, but not too late for the thousands who were saved by The Statesman’s reporting and the government’s tragically late, but ultimately effective intervention.

If one wants to explore the gruesome depths to which governmental negligence, no information, and authoritarianism can drive humanity, there is no better nor chilling source than Tombstone: The Great Chinese Famine—1958-1962 (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2012) by Yang Jisheng. Mao’s iron-fisted grip on the people, non-existent free press, suppression of dissent, and a state-mandated, one-size-fits-all approach to food production left 36 million people dead from starvation and an estimated 40 million children not born due to maternal fertility disorders from extreme malnutrition. (My full review of the book can be found at Famine | Mark Winne). When I think of food insecurity in America, I’m always emotionally drawn to one indicator, that of parents skipping meals so that their children can eat. Yet China’s great famine brought people to an unimaginable level of desperation, where, Yang Jisheng tells us, parents, driven mad by hunger, ate their own children.

In case I haven’t provided a sufficient number of lessons from the past, I’m going to take one giant step backward to the Roman Empire with the help of Dr. Kyle Harper whose breathtaking lecture I attended this June Kyle Harper – Climate Change and Contagion – Complex Crises Past and Present. As a paleoclimatologist, Dr. Harper examines human history—in this case, the written records of the Roman Empire—and climate history through such specimens as tree rings, ice cores, and microscopic particles found in ocean sediment off the southern coast of Italy. These writings and samples allowed him and his colleagues to assemble enough data to present an accurate profile of life during the periods that we refer to today as the Fall of the Roman Empire (there were several “falls” from about 250 to 550 Common Era).

What was learned? What contributed to the falls?

Food crisis, famine from climate eventsClimate events: Volcanic explosions “veiled” the sun for over a year causing a mini-Ice Age and steep temperature drop around 540 CEInvasion and defeat from outside forces (“barbarians”)Monetary crisis, breakdown in financial structureLegitimacy crisis, fragmentation of political and governance structuresPlague of Cyprian (around 250 CE): “The disease grew severe and indescribable, having struck Rome (and) Greece …. The scribes in Rome registered 5,000 or even more dead (who succumbed to the disease) every day.” Dexippus of AthensPlague of Justinian: about 541 CE; the worst health event of the first millennium and the pre-cursor to the Black DeathDr. Harper drew two powerful conclusions from this catalogue of events. The first suggests a positive outcome is possible. When climate catastrophes occurred, if political stability was the order of the day, the negative impacts, such as famine did not happen. Today, we call this resilience. Likewise, when political instability rules the day, severe climatic events and pandemics, often accompanied by other social, political, and economic challenges, are more likely to lead to famine. I view this as complementary to the research of Padraic Scanlan and Amartya Sen.

The second conclusion offers less hope. Rome and the rest of the world up until about 1900 had one advantage we don’t have today, they didn’t suffer from nearly 2 degrees increase in global temperatures. Up until that moment when the anthropogenic effects of carbon-based energy took over, the earth’s temperature rarely varied by more than half a degree. Devastating and unprecedented floods, hurricanes, typhoons, droughts, and other climate events, including wildfires, are cascading upon us so rapidly that scientists and those who monitor that activity can barely keep up, let alone analyze it. For instance, “The First Street Foundation, a private risk-assessment firm, concluded that floods previously considered to be one hundred-year events have become, on average, sixty-two-year events.” (The New Yorker, 7/28/25).

Dr. Harper concluded his lecture with this slide: “Scary thought: we can also probably handle a lot of climate change, until our constitutional system disintegrates, the dollar collapses, the US splits into two, the next COVID appears, and worldwide crop failure happens simultaneously.” The average ancient Roman lived to about 30 years old compared to today’s developed countries’ average lifespan of about 80. The two biggest causes of that vast difference in those lifespans, according to Harper, are vaccines and basic public health advances such as clean water. Gazing up at his last slide, Harper remarked, “all of this doesn’t feel as remote as I’d like it to be.”

I would say that it feels eerily close given Trump’s sacking of science, universities, health research, nutrition programs, economic wisdom, ethical standards, and everyday common sense. The barbarians are no longer at the gate—they are inside the walls!

Though this example might seem like small potatoes compared to the rotting potatoes of 1846, our food policy council in 2001 discovered that 6000 women, infant, and children had been inadvertently dropped from the WIC rolls in the City of Hartford, Connecticut. This was due to some bureaucratic bungling that city government is, unfortunately, heir to and can easily act indifferently unless advocates scream at them. The negligence was severe enough to send a strong bolt of food insecurity into the lives of the city’s most vulnerable people. The food policy council marched into the mayor’s office threatening to go to the media if these WIC clients weren’t restored to the program immediately. The problem was fixed in two weeks.

Yes, we need more and better food policy councils to be the informed and active citizenry that holds both the ignorant and the malicious accountable. As Scanlan says, however, at the conclusion of his book, “famine in the twenty-first century, as in the nineteenth, is a disease of modernity—of war, of ecological accident, of climate change, of the vicissitudes of markets acting on the vulnerable.” Yet, looking at today’s events in Gaza and back at Stalin, Mao, and Pol Pot, I also can’t help but think that there is something unremittingly dark at the core of the human soul capable of making plausible arguments for death by starvation. The only plausible answer must be, “where there is a functioning democracy, opposition parties, and a free press,” despots, both here and abroad will one day fall like so many cabbage heads into a hand-woven basket. And with the good sense of a democratic people, and the compassionate hearts we are all born with, catastrophes will not mean famine and starvation.

June 29, 2025

Strawberry Fields…Forever?

According to my Word Press counter,  “Strawberry Fields Forever?” is my 200th blog post since I began markwinne.com in 2007! I don’t honestly know what to do about that other than to simply make my readers aware of what I guess is a milestone. I thought about honoring the occasion by sending out refrigerator magnets or meme coins, but my marketing staff said we don’t have the budget for it. I guess we’ll just have to celebrate by offering these posts for free. They are free already, you say? Well, now they’re even freer! Happy 200th!

“Strawberry Fields Forever?” is my 200th blog post since I began markwinne.com in 2007! I don’t honestly know what to do about that other than to simply make my readers aware of what I guess is a milestone. I thought about honoring the occasion by sending out refrigerator magnets or meme coins, but my marketing staff said we don’t have the budget for it. I guess we’ll just have to celebrate by offering these posts for free. They are free already, you say? Well, now they’re even freer! Happy 200th!