Cosmic Journey

Click here for the accompanying video for Cosmic Journey.

Many years ago I was commissioned to give a series of astronomy lectures. One of these was called "Cosmic Journey" and was intended to give the uninitiated an overview of the entire cosmos. For this I produced a 40-minute video (with music) to which I provided the narration. In this blog post I have reproduced the narration in written form and provide a link to the video posted on YouTube.

The video takes uson a journey – a journey from planet Earth to the farthest depths of space, to the very edge of the visible Universe. Along the way we will find many fascinating objects, learn about how they formed, how they work and how they die. We'll meet some strange and beautiful ideas and see how the powerful method of science explains what we encounter.

Gazing at the night sky from Earth, it is easy to picture the Universe as static and peaceful. The same stars cross the sky every night and only the occasional shooting star or solar eclipse reminds us that the heavens are busy. However, on our journey we will find that the Universe is changing all the time. It evolves on timescales that dwarf our human lifetimes. At times the Universe can be violent, at other times serene or perplexing, destructive or creative. But it never ceases to inspire and intrigue us. It is a truly beautiful and remarkable place.

What you will see in this video is a simulation of the Universe, but one that uses the latest astronomical imagery and data. This voyage is as close to the reality of what you would see if you were actually making the journey, but as we will find, there are limits to how real we can make it.

Before we leave, it should be pointed out that this is an impossible journey. In order to reach the farthest depths of space in the few minutes at our disposal, we would have to travel at many billions of times the speed of light. This is impossible because the speed of light is the ultimate speed limit in the Universe.

As we make our journey, we will soon realize that the Universe is a very big place. Familiar units, like miles or kilometers, are useless when measuring the vast distances that we will encounter.

We will be using several units of measurement as we proceed on our journey. The first is convenient for measuring distances within our own neighbourhood, the Solar System. It is called the Astronomical Unit, abbreviated AU, and is defined as the average distance between the Earth and the Sun. An AU is equal to about 93 million miles or 150 million kilometers.

Most people have heard of the second unit. It is the light year, abbreviated LY, and is equal to the distance traveled by light in one year. It is about 6 trillion miles or 10 trillion kilometers.

The final unit of distance we will be using is called the Mega-parsec, abbreviated Mpc, and is convenient for distances outside our own Galaxy. The nearest large galaxy to our own, the Andromeda Galaxy, is about 1 Mpc away. Be warned; the distances of astronomical objects are extremely difficult to measure. There are several methods. For example, it is possible for some objects to know exactly how bright they are intrinsically. Comparing this to how bright they appear to us on Earth reveals their distances. But all these methods have some uncertainty which means the distances quoted are not that precise. The overall scale of the Universe is pretty well established, but the distances to many objects are not that accurate.

As we journey outwards the timing numbers (minutes: seconds) give an indication of where in the video the text refers.So, let's begin...

00:41: As we pull away at greater and greater speed we begin to see planet Earth beneath us. This is our home. Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the largest of the ‘terrestrial’ planets – those that have rocky surfaces. The Earth is a slightly squashed sphere with a radius of about 6,371 kilometers. It spins on its axis in just under 24 hours and revolves around the Sun in 365.25 days, or thereabouts.

We know a great deal about the Earth, simply because it’s under our feet and therefore easy to study. The Earth is believed to be 4.55 billion years old. 71% of the Earth's surface is covered with water. Earth is the only planet in the Solar System on which water can exist in liquid form on the surface. The Earth's atmosphere is about 77% nitrogen, 21% oxygen, with traces of argon, carbon dioxide and water. The carbon dioxide is in fact an important part of the atmosphere. The natural ‘greenhouse effect’, which you have all heard about, is responsible for maintaining the Earth’s temperature at about 35 degrees above what it would normally be. Without it, the Earth would be frozen and life would not be able to survive here.

And of course, the fact that life exists here, is what’s important to us. This Blue Marble, a tiny speck in the vastness of space, contains everything we know and love. It is a precious place.

In a moment we will be leaving this precious place behind and heading off into space. We will have to attain some pretty monumental speeds on our journey so we will accelerate away from Earth extremely quickly.

03:15: The first object we will encounter of course is the Moon, our nearest celestial neighbour. The Moon is a sparse, cold and dusty place. But it is distinguished by being the only other celestial body that humankind has visited, although some people seem not to be convinced of that. Astronomers now believe the Moon was formed from debris made by the impact of the primordial Earth with another planet, perhaps the size of Mars.

03:40: We are now heading towards the inner planets, those closer to the Sun than us. The first planet we come across is Venus, which incidentally is now visible just before sunrise low in the East. Venus is a very hot planet due to its closeness to the Sun and because it has an extremely dense, cloudy atmosphere of carbon dioxide and sulphuric acid. The surface temperatures reach 460 degrees C.

04:02: We’re now heading in to the closest planet to the Sun – Mercury. Mercury is similar in appearance to the Moon. It is heavily cratered, has no atmosphere and no natural moons. It rotates on its axis very slowly so that the Mercurian day is very long, about 59 Earth days. This means that there is a huge difference between the daytime and nighttime temperatures. Daytime averages are about 420 degrees C and nighttime temperatures about -170 degrees C.

04:30: Now we are turning away from the Sun again and flying back out past the Earth’s orbit towards Mars, the red planet. Mars is perhaps the planet most resembling Earth. It is slightly smaller, has a thin atmosphere and shows surface features like impact craters, valleys and mountains, volcanoes, deserts and polar ice caps.

04:50: The geology of Mars is spectacular. Valles Marinerisis a vast canyon system that runs along the Martian equator. At more than 4,000 km long, 200 km wide and up to 7 km deep, the Valles Marineris rift system is the largest canyon anywhere in the Solar System. It is actually a huge crack in Mars’ surface formed as the young planet was cooling. There is evidence that parts of this vast valley have been flooded by water in Mars’ past. In fact, it appears the primitive Mars may well have had significant quantities of liquid water on the surface, prompting suggestions that life may have developed there, but now any water still on Mars is locked up in the permafrost and the polar ice caps.

05:45: We are now flying towards Olympus Mons, the largest volcano anywhere in the Solar System. Olympus Mons is a shield volcano 624 km in diameter and 25 km high, three times as high as Mount Everest.

06:00: Leaving Mars behind, we’re heading towards the planet Jupiter, but before we get there we will encounter the main Asteroid Belt of the Solar System. Asteroids are rocky bodies, representing material left over from the formation of the Solar System. The Asteroid Belt is actually mostly empty. You could quite easily pass through the Asteroid Belt with little risk of a chance collision. Deep space probes do this all the time.

Asteroids vary greatly in size, from a diameter of 975 kilometers for Ceresand over 500 kilometers for Pallasand Vesta down to rocks just tens of meters across. A few of the largest are roughly spherical and are very much like miniature planets – in fact they are now called ‘dwarf planets’ rather than asteroids. The vast majority, however, are much smaller and are irregularly shaped.

07:00: We’re now arriving at the planet Jupiter. This is the largest planet of the Solar System – in fact it has two and a half times the mass of all the other planets put together. Jupiter is a ‘gas giant’ composed mainly of hydrogen gas with a sprinkling of helium and other elements. Jupiter has a total of 63 moons.

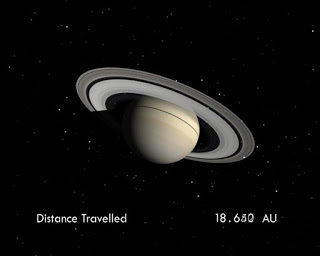

07:30: Saturn, the sixth planet from the Sun, and another gas giant, is second only to Jupiter in size. Again it consists mainly of hydrogen. The surface of Saturn is pretty featureless, unlike Jupiter, but it makes up for it with its beautiful ring system. Saturn is of course what school kids draw when they draw a planet.

07:45: The rings of Saturn are composed mainly of water ice particles. These range in size from dust-sized grains to large car-sized objects. Although the rings extend some 120,000 km out from their mother planet, they average only about 20 meters in thickness. The rings have a very complex structure, consisting of thousands of rings with different average densities, interspersed with dark gaps. This structure is the result of the gravitational perturbations of Saturn, but also because a large number of tiny moons clear out areas of debris or shepherd the icy material into tight rings.

It should be pointed out that all four gas giant planets, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune, have ring systems, but the Saturnian one is by far the most spectacular. All of them can be seen from Earth, but Saturn’s rings are the only ones you’ll be able to spot with a modest-sized telescope.

09:05: We now come to the planet Uranus. Uranus is a pale blue-green colour. It has a system of 27 moons, although the largest, Titania, is less than half the size of the Earth’s Moon. The most unusual thing about Uranus is that it is tipped on its side – the rotation axis is almost in the same plane as its orbit. This gives Uranus a very strange seasonal pattern. Each pole gets about 42 years of night followed by 42 years of day.

09:30: We are now visiting the eighth planet from the Sun, Neptune. Neptune is about 17 times the mass of the Earth and has a radius about four times the Earth’s. Its distinctly blue colour shown here is real. The small amount of methane in the atmosphere, which again is chiefly hydrogen and helium gas, absorbs red light, resulting in a beautiful azure planet. Its interior contains water, ammonia and methane ices. At a depth of 7000 km, the conditions are just right for methane to decompose into diamonds, which then rain down on the rocky core below.

10:00: We are now heading out towards the most distance parts of the Solar System. As we journey out we may just possibly come across a lone comet. The nucleus of a comet is a small object consisting of rock, dust, ice and frozen carbon dioxide, methane and ammonia. When close enough to the Sun, the solar radiation evaporates large quantities of these volatile materials forming a tail. The nucleus of a comet can be a few hundred meters across up to perhaps 40 km wide, but the tail can extend to one astronomical unit. Most comets have very elongated orbits around the Sun so that they spend most of their time in the cold depths of the outer Solar System. Far beyond the orbit of Pluto, a quarter of the way to the nearest star, there is a vast ocean of comet-like objects known as the Oort Cloud.

11:00: We are now approaching the final planetary object we will encounter in the Solar System. Until recently, Pluto was a planet, but with the discovery of many objects similar to Pluto in the outer Solar System, notably the object called Eris, which is bigger than Pluto, astronomers have re-designated it as a ‘dwarf planet’. Pluto is no longer considered a planet for the same reason the asteroids are not.

11:25: We have now come to the edge of the Solar System, our little corner of the Universe. We will now begin to pick up speed, and as we do so, we will see the Sun and its faint retinue of planets receding and dimming in the distance. But before we leave the Solar System behind, we should talk briefly about perhaps its most important member; the Sun.

11:35: The Sun, that vital source of energy that in fact allows our very existence, is a star like any other. It is a pretty average sort of star – totally unremarkable – just like the many billions of other stars we can see in the sky. Stars are luminous balls of plasma. There is so much material in a star that the pressure at the centre creates enormous temperatures, tens of millions of degrees. Under these conditions, atoms undergo a process called ‘thermonuclear fusion’ – that is, small atoms like hydrogen are forced together to form heavier elements, releasing energy as they do so. It is exactly the same process of energy release as in a hydrogen bomb. This process of ‘nucleosynthesis’ builds up heavier and heavier elements in a series of different nuclear reactions. In fact, apart from the hydrogen in your bodies, all the heavy elements which are part of you must have been formed in the heart of a burning star.

12:25: We are now beginning to increase our speed enormously. We are now light years from Earth and as our speed increases we will begin to see the individual stars of our part of the Milky Way Galaxy begin to move. There are many kinds of stars. Massive ones, small ones, hot ones, cold ones, old ones, young ones, single ones, binary ones, multiple ones, new-born ones, dying ones. Their range of properties, like mass, temperature, age, give rise to a zoo of exotic and interesting objects. We don’t have time to look closely at all the different types of stars, but they include objects called red giants, white dwarfs, blue supergiants, brown dwarfs, black holes, microquasars, proto-stars, neutron stars, X-ray binaries, cataclysmic binaries and so on.

12:50: Stars form out of a compressed cloud of gas. There are many processes that can trigger a cloud of gas in space to begin collapsing in on itself. One way is a nearby supernova, or exploding star, which can send shockwaves through the interstellar medium, disturbing the precarious equilibrium. If enough matter coalesces at the centre of the cloud, a new star will be born. The pressure and temperature at the heart of the proto-star rise until thermonuclear reactions begin and the star sparks into life. The leftovers of this process, a tiny fraction of the original mass of the cloud, can form a planetary system like our own, containing planets, asteroids and comets, all the bits and pieces we’ve just seen in our own Solar System. As the new star begins to shine, the radiation it creates blows away the remaining material.

13:45: We’re still heading away from the Sun on our journey. We’ve moved so far now that the typical patterns of stars we’re used to seeing in the sky have completely changed.

Astronomers can deduce a lot about the stars by analyzing the light they radiate. All atoms absorb or emit radiation at specific wavelengths (or colours) of light, and each of the chemical elements, such as hydrogen or oxygen, has its own signature of absorption or emission lines. Nature has provided us with a convenient fingerprint of a star’s constituent elements in the spectrum of its light. By splitting starlight into its component colours, with something as simple as a prism, the astronomer can identify the absorption or emission lines in the star’s spectrum and deduce its composition. What’s more, it is also possible to determine things like temperature, density, pressure, luminosity, size, age, magnetic field, rotation rate, speed and the mass of stars simply by analyzing their spectra.

14:35: We have talked about how stars form. Let’s now look at wherethey form. To make a star we need clouds of hydrogen gas. Such regions of space are known as ‘nebulae’, which is Latin for ‘mist’. Nebulae come in many shapes and sizes and have many processes going on inside them. Some nebulae shine simply by reflecting the light from nearby bright stars while some give off their own light when the radiation from hot stars excites the hydrogen atoms inside the nebula. Some nebulae are totally dark and we only know they’re there because they block out the light of objects behind them.

Many of these nebulae are the birth places of stars. Astronomers call them ‘stellar nurseries’. These regions of space can be quite stunning in their complexity and beauty. In them we can see the clouds of gas themselves and faintly glowing within these, the first rays of light from infant stars. Once stars have formed within a complex cloud of gas, they can have a significant effect on their environment. The intense radiation they give off begins to mould and shape the clouds of hydrogen gas. The radiation also ‘ionizes’ the nebular gas, causing it to glow in different colours – red, blue and green. We have also seen proto-planetary disks inside nebulae. These are rotating disks of material orbiting very young stars and which will presumably form planetary systems.

16:10: How a star lives its life depends on how much mass it has. Massive stars live fast and die young. Smaller stars live longer and just fade away. A young star has plenty of hydrogen to fire its furnace. The thermonuclear reactions result in hydrogen being converted slowly into helium and the energy generated balances the gravitational contraction exactly.

Eventually the star’s hydrogen fuel is all used up and the energy source is switched off. What happens then depends on the mass of the star. Low mass stars will expand to become Red Giant stars. Massive stars will contract and attain a core temperature high enough to start fusing helium atoms instead of hydrogen. Really massive stars can also synthesize much heavier elements in their cores such as aluminium and silicon. However, no star can synthesize elements heavier than iron because those nuclear reactions require energy rather than produce it.

17:00: Let’s take a look at some exotic objects as we travel through the Galaxy. Here is an example of a really massive star. It is called Eta Carinae, and it lies within the Carina Nebula. Eta Carinae is believed to have a mass more than 100 times the Sun’s. It is so massive, and has therefore evolved so quickly, that it is almost certainly about to die. Such a star would end its life in a massive explosion called a Supernova, which we’ve already mentioned. Eta Carinae seems to be getting ready to blow itself apart. Recently, in 1841, it brightened considerably and threw off two lobes of material which form the ‘Homunculus Nebula’. It may not blast itself to pieces during our lifetimes, but there are lots of astronomers hoping it will!

17:55: This object is called V838 Monocerotis. In 2002, a previously un-catalogued star started brightening and produced this strange expanding nebula. It may be a massive star preparing to die or it may be that the star concerned has swallowed up several large planets as it expanded.

18:08: Occasionally, stars cannibalize each other. In this example we see a black hole slowly devouring its companion. Blowtorch-like jets, shown in blue, are streaming away from the black-hole system at 90% of the speed of light.

18:25: This object is called the Cat’s Eye Nebula and is an example of a ‘planetary nebula’. Planetary nebulae have nothing to do with planets – it’s just that when they were first discovered, their round shape led many to confuse them with planets. A planetary nebula is the radiant afterglow for most stars in the Universe, including our own Sun. Before dying, most stars gently eject their outer gaseous layers and thereby produce bright nebulae with amazing shapes.

18:50: We are still traveling at colossal speed through the Milky Way Galaxy. The patterns of stars, or constellations, are now completely unrecognizable. There are something like 200 billion stars in our Galaxy, although the human eye can see at best about 2000 on a clear, dark night. The brightest star in the sky is called Sirius. The nearest star beyond the Sun is called Proxima Centauri and is 4.25 light years from Earth. The star furthest from Earth that can be seen without a telescope is probably the star called Deneb at 3,200 light years.

19:30: Now, all stars must eventually die. We have already mentioned several things that can happen to them on their death beds. One eventuality is a supernova explosion, like this one. Supernovae are responsible for creating the chemical elements heavier than iron. If you’re wearing some silver or gold today, take a look at it – the atoms in what you’re wearing were made inside a supernova. In fact, all the elements in the Universe, except hydrogen and helium, have been cooked up in stars or supernovae since the Universe began.

Supernovae are responsible for returning the material that makes stars back into space – a kind of stellar recycling. Not only that, but as we’ve heard, the shock waves from supernovae can trigger the formation of new stars. It is an endless cycle of death and rebirth.

20:05: Here we see a Red Giant star being cannibalized by a companion star. The Red Giant explodes as a supernova to leave a neutron star or possibly even a black hole.

20:25: In this example, we see a White Dwarf star sucking material off its massive companion. The hydrogen gas builds up on the tiny White Dwarf until its mass reaches a critical limit when it explodes as a titanic fusion bomb, throwing its companion off into space.

20:45: Some massive stars can give rise to pulsars. These tiny stars, perhaps only a few tens of kilometers across, often reside in the hearts of supernova remnants. They are essentially the leftover, highly dense cores of stars that blow themselves apart. Pulsars are rapidly rotating, magnetized stars which emit radio waves along the magnetic axes. When one of these beams crosses the earth, we hear a radio pulse, hence the name pulsar.

21:15: Finally, really massive stars can produce black holes when they destroy themselves. Far from being science fiction, black holes are a reality. Although they can’t be seen directly, astronomers can infer their presence

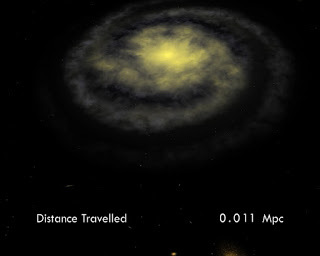

21:30: We are now approaching the edge of our own galaxy, the Milky Way. The Milky Way is a flattened disk in shape. We have been moving almost straight up out of the plane of the Galaxy, which means we will leave the Milky Way after traveling only a few thousand light years or so. The Sun is located about two-thirds of the way out from the centre of the Galaxy, which lies about 25,000 light years away.

22:05: As our speed continues to increase and we pull away from the Milky Way, we will see that we begin to loose sight of the individual stars in the Galaxy. Only the very brightest stars still stand out. Instead, we begin to perceive all those billions of stars as just a hazy patch of light.

22:30: Our Galaxy, like our Sun, is just like any other. There is nothing especially unique about it. The Milky Way is what we call a barred spiral galaxy. You have seen images of the spiral shape of galaxies. We name the spiral arms of the Milky Way after the constellations in which they appear in the sky. The Sun is not actually within one of the main spiral arms of the Milky Way – it is in a small offshoot of the Perseus Arm which we call the Orion Spur.

22:45: We can now see the entire Milky Way galaxy receding from us. Immediately, we notice that our Galaxy is not entirely isolated in space. There are numerous small, irregularly-shaped galaxies close by. These galaxies, which total around 50 or so, form a small clustering within space which we call the Local Group. The diameter of the Local Group is about 10 million light years.

23:15: We are about to pass the nearest large galaxy to our own, in fact, the largest galaxy in the Local Group. It is called the Andromeda Galaxy and is actually the furthest object that the human eye can see, at a distance of about 2.5 million light years. You need a really dark and clear sky, and good eyesight, but it is quite easy to see if you know where to look. You will see that the Andromeda Galaxy also has a number of small companion galaxies. We can now see the entire Local Group of galaxies, our backyard in terms of extragalactic space.

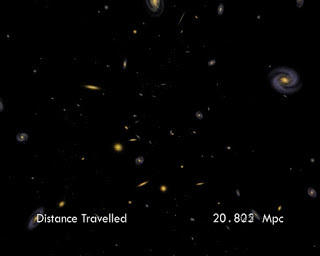

23:50: Wherever we look in the sky we see galaxies – billions of them. But for all their beauty and diversity, they are made mostly of empty space. The distances between the stars in a galaxy are huge compared to the size of the stars. This means that two galaxies in a head-on collision would essentially pass right through each other without a single star having collided with another. However, this doesn’t mean they get away unscathed. The gravitational interaction of the galaxies can easily disrupt the stars within, so that the entire galaxy undergoes a dramatic shift in its structure. It can also make galaxies undergo periods of accelerated star formation. Such galaxies are known as ‘Starburst Galaxies’. Interacting galaxies are surprisingly common in the Universe. In some cases entire galaxies end up merging together.

24:15: Here we can see some simulations of how galaxies interact, comparing them to actual images of such galaxies. These galaxy collisions take place over many millions or even billions of years. Incidentally, our Milky Way Galaxy is actually devouring its closest companion, a small galaxy called the Sagittarius Dwarf Elliptical Galaxy. There is also good evidence that the Milky Way is cannibalizing its two largest galactic neighbours, the Small and Large Magellanic Clouds. Astronomers have detected streams of hydrogen gas being sucked towards us by the pull of the Milky Way.

25:00: We are now beginning to leave the Local Group of galaxies behind us. We can just about see the Andromeda Galaxy and our own Milky Way Galaxy off in the distance. Astronomers have found that the galaxies in the Universe are not distributed randomly through space - they clump together in clusters. Our Local Group of galaxies is a small part of a huge grouping known as the Virgo Supercluster.

25:40: We are now passing through the densest part of the Virgo Supercluster, known as the Virgo North Cluster. This is a dense grouping of several thousand galaxies at a distance of about 59 million light years. It is centered on a huge elliptical galaxy called M87. From Earth, the entire cluster subtends an angle of about 8 degrees on the sky – that’s about 16 times the size of the full moon! This huge grouping of galaxies dominates this part of the Universe and the Local Group is just an outlying, minor part of the larger structure. What better evidence is there that we occupy an insignificant position in the Universe?

26:10: Now, there is an interesting kind of object in space which isn’t really an object at all – it’s an optical illusion. These objects were first predicted by Albert Einstein when he realized that matter actually warps the space around it. Einstein postulated that a very massive object would warp space so much that light from more distant objects would be bent around it, effectively acting like an enormous lens. They are called ‘gravitational lenses’. In these objects the light from incredibly remote galaxies is bent to make multiple images of the same distant object.

26:40: We can now see the Virgo North cluster receding into the distance. We’re now running into a bit of a problem with our simulation of the Universe. The problem is that the galaxies are not very bright. This is actually what we’d see out there in intergalactic space – almost nothing – because all the distant galaxies are so faint. So, for us to get an idea of the large-scale structure of the Universe, we need to change from a simulation to a visualization. We are now going to turn up the brightness of all the galaxies in the Universe so you can see pretty much all of them. We’re also going to make them just simple dots so things don’t look too complicated. We’re looking at the same thing as we change over, but we can suddenly see a whole lot more than was visible before.

27:00: We can also see that there is some kind of structure to the distribution of galaxies in the Universe. The galaxies form clusters and superclusters; and between them lie almost empty ‘voids’. Looking even closer, astronomers have found that the structure of the Universe is more like a mesh of bubbles, the voids, connected with these huge sheets or filaments of galaxies. The Universe in fact looks like the inside of an Aero chocolate bar.

27:50: We are now starting to accelerate again in our outward motion. As we do so, we can see more and more galaxies, clusters, superclusters, voids and filaments coming into view.

The data you are looking at is real astronomical data. Astronomers have catalogued the positions and the distances to many millions of galaxies. This visualization uses that data to give you a 3-dimensional view of the distribution of the galaxies throughout space. The view we have here is using the data from just a single catalogue of galaxies, but as we shall see, there are many more catalogued galaxies. So, what you see here is still missing a lot of objects, but it still gives you a good idea of the large-scale structure.

28:55: We have now stopped our motion out into the Universe, so we can pause and get a better look at the structures we can see. Our view is next rotated, as if we were orbiting around the Earth. The Virgo Supercluster is still very prominent towards the centre of our view.

29:10: Look out for a particular area as it rotates past us. Here, you will see an area in which there appears to be few, if any, galaxies. The reason is that we must observe the sky from here on Earth and the disk of our own Galaxy obscures our view. So, it is difficult to see any galaxies along the plane of the Milky Way. This is why the Universe appears to be empty in this gap, known as the ‘zone of avoidance’.

So, perhaps you’re thinking that we have moved sufficiently distant from Earth to see most of the Universe, and that we are nearing the end of our journey. Well, in fact, we have an awful lot further to go than this. The volume of space we’re currently looking at is only about one 10 millionth of the total volume of the Universe. The Universe really is a terribly big place!

So, we’re going to start moving out again in a moment. When we do, we’ll be moving at our greatest speed yet. We will also add more and more of the galaxy catalogues, to fill up the empty space through which we’re moving. It isn’t long before our view will be almost completely covered with galaxies. As we move out this gives you an idea of just how many galaxies are out there. Astronomers estimate that there may be 500 billion galaxies in the Universe. Obviously, there are not 500 billion galaxies in our visualization. In fact, there are only about 2 million galaxies shown here.

30:15: You will notice as we move out that the galaxies are often concentrated in sheets or cones. The reason for this is simply the method used to find them. The sky is actually very big and the galaxies themselves are very small on the sky. So, to survey them takes a long time. Most studies choose a small patch or strip of sky to concentrate on. So, when we include these catalogues, you are seeing just a small sample of the galaxies in the sky and it is obvious where the astronomers have been pointing their telescopes. You need to imagine of course, that the entire Universe is filled with galaxies, rather than just the bit we’ve had time to survey with our instruments.

30:22: A black hole is an object so dense that its escape velocity is greater than the speed of light. Nothing can ever escape from black holes, though we know they are there because of their effect on their environment. Astronomers believe that at the centre of most galaxies, maybe even all galaxies, there are supermassive black holes, millions of times the mass of the Sun. These objects are devouring huge quantities of material. The energy created by this galactic cannibalism generates beams or jets of energy that race out of the galactic centre at incredible speeds. If one of these is pointed towards Earth, we see a very bright, very distant point of light of incredible energy. We call these objects ‘quasars’. They are the brightest, most energetic and most distant objects in the Universe.

31:15: Now, astronomers have discovered that the Universe is in fact expanding. This means that the distant galaxies are actually receding from us. The further away they are, the faster they recede. But perhaps the astute amongst you will realise that this leads to a problem in our visualisation. Because it takes time for the light from distant objects to reach us here on Earth, we are in fact looking backwards in time as we look out into the Cosmos. In fact, we see the most distant objects in the Universe as they were even before the Earth and Sun came into existence. If we are seeing them in the distant past, and the Universe is expanding, then right now they are no longer where they were when the light we see was emitted. So, in a sense, we have had to travel backwards in time on our journey in order for it to be correct.

Let’s briefly mention a couple of the current mysteries of the Universe. Astronomers have found that perhaps 99% of the matter in the Universe is invisible. We call this ‘dark matter’, and although we can’t see it, we know it must exist because otherwise galaxies and clusters, or in fact the whole structure of the Universe, would not be able to hold themselves together. Some of the dark matter may be contained in just very dim and therefore invisible objects, but most of it must be some weird form of matter that has not yet been detected. Even weirder is something called ‘dark energy’ which has to be the most abundant stuff in the Universe and yet we have almost no idea what it is. Again, we know it exists because it is actually making the expansion of the Universe speed up, counteracting the force of gravity which would naturally make the expansion slow down. Finding out what ‘dark matter’ and ‘dark energy’ actually are, are high on the astronomer’s to-do list.

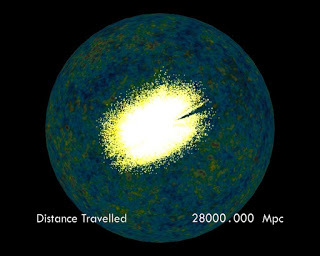

32:45: We have now added the final object on our journey outward into the Cosmos. This coloured wall surrounding the galaxies is known as the Cosmic Microwave Background. This is an incredibly faint glow which is the left over radiation from the formation of the Universe. This relic radiation appears to be at a distance of about 46 billion light years and represents the edge of the visible Universe.

In order to see the whole Cosmos of course, we have had to step outside it - we have actually overshot the wall of the Cosmic Microwave Background and moved outside the visible Universe.

33:10: We are now rotating the entire Universe so we can see its overall structure. Obviously, the galaxies we see do not actually stop about two-thirds of the way out. It’s just that we astronomers are waiting to build even bigger telescopes which will reveal what lies in those uncharted, distant regions.

33:45: The expansion of the Universe that we mentioned implies that the Universe began in a titanic explosion called the Big Bang, about 13.7 billion years ago. The Big Bang represents the moment that the Universe came into being and at that moment all of the matter and energy of the Universe was concentrated into a single point.

Just after the Big Bang, before the formation of stars and galaxies, the distribution of matter was fairly smooth. After time, gravity started exerting its influence and slowly small clumps of matter began forming. Where the density of the clumps became higher, even more matter was attracted and a competition between gravity and the expansion of space took place. Where gravity won regions stopped expanding and started to collapse in on themselves. The first stars and galaxies were born. Where the matter density was highest, at the intersections between the large web-like structures of matter, the largest structures we know were formed – clusters of galaxies. Finding out exactly how these structures we see in the Universe first formed and evolved is another important subject in modern astronomy.

35:00: We have now completed our journey to the furthest depths of space, to the edge of the visible Universe, in fact, beyond it. It only remains for us to return to planet Earth.

35:25: We are now reversing our motion back towards the Earth. Again, we will move at incredible, in fact impossible, speeds. As we begin the journey back our speed will in fact be 24 million billion times the speed of light. We will turn off the galaxy catalogues as we proceed and eventually change back from visualization to simulation. We will decelerate significantly as we head in towards our local bit of the Universe, plunge into the Milky Way Galaxy to find our own star, the Sun, and home planet, Earth. Enjoy the ride home!

Published on August 15, 2016 05:57

No comments have been added yet.