An A-Z of the IWOME

The Illustrated World of Mortal Engines is published this week. It was written by me and Jeremy Levett, with Jeremy doing the bulk of the actual work while I just fired suggestions for weak puns at him from Dartmoor and Iceland. It’s also lavishly illustrated by what can only be described as a glittering galaxy of star illustrators.

To mark the completion of this epic project, we’ve compiled the following A-Z guide…

Part One: A – F

A is for Art

A very important part of the Illustrated World is right there in the title: ILLUSTRATED. The original Traction Codex had a number of lovely drawings by Philip (some of which we’ll be putting up in these blogs – only one made it into the final IWOME), but the IWOME has seven different artists from all across the world: Aedel Fakhrie, Ian McQue, Maxime Plasse, Rob Turpin, Philip Varbanov, David Wyatt and Amir Zand. Ian and David have already been involved in Mortal Engines before (both have done a set of covers, Ian illustrated Night Flights and David illustrated Philip’s Larklight series). These artists all have quite different styles, and you can find at least four different versions of London in the IWOME.

Jamie, the design chap at Scholastic, managed a great back-and-forth of illustration briefs, sketches and final artwork between us and the artists to make everything just-so. It was very cool seeing the ideas we came up with given form by such skilled artists, especially when some of said ideas were really quite silly…

It was an interesting process: a number of times an artist came back with something that wasn’t exactly what we imagined but was actually better. Some needed a bit of changing, and a couple of pieces took ages of back-and-forth email to get right. But hopefully, you won’t be able to tell which…

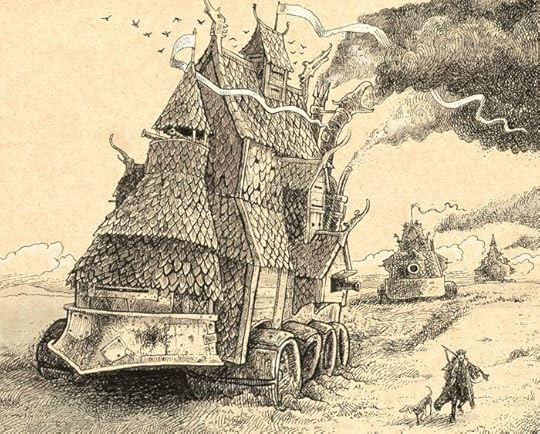

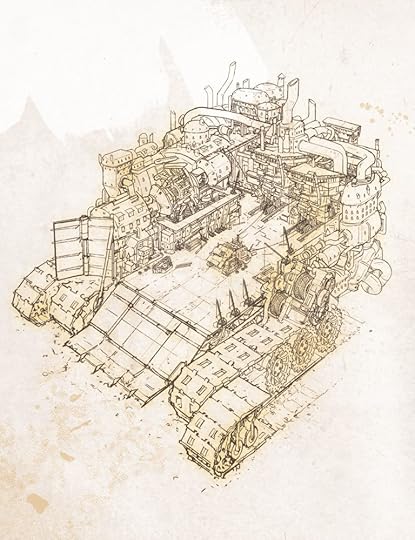

Weaponised stave churches on the move, around 350 TE

B is for Black Centuries

“…a savage age, when life was cheap, and most people would happily have sold their own children for a tin of rice pudding.”

The Black Centuries occupy most of the time between the world we have now and the world of Mortal Engines. They’re a period of horrible upheaval and universal misery, punctuated by lots of localised problems which made moving around all the time a logical way of life. They’re also a Dark Age about which very little is known or understood, as people were too busy eating radioactive cockroaches and worrying about runaway climate change* to write much down.

The properly-worked-out history of the Mortal Engines world is a self-contained timeline lasting around a thousand years, with the Fever Crumb books happening halfway through, and the Mortal Engines quartet at the end. But something which often comes up in online discussions is: how far in the future? What’s 1TE in AD? We never worried about an exact answer to how long the Black Centuries lasted – some people within the world of Mortal Engines think they know, but some of them are also convinced people coexisted with dinosaurs.

From a narrative point of view, the Black Centuries are a very useful way of drawing a thick (black!) line underneath the world-that-was and setting the scene for something else. But how many Centuries there really were is open to interpretation…

* This is a suggestion, as well as a descriptor.

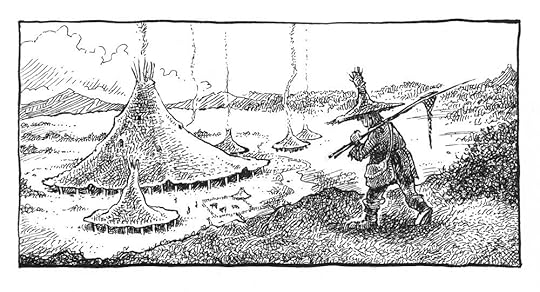

Everyday life in the Raffia Hat Culture

C is for Canon…

…and Continuity, and Contradiction, and all those other words about the ambiguity which creeps into worlds written across many years or spread across different media adaptations.

Ambiguity is quite fun and, from a writing perspective, can be very useful! But it can also be pretty frustrating when the pieces don’t fit together. We’ve done our best to make it all work, but it’s probably inevitable there’ll be a list of “Differences between the IWOME and the Mortal Engines books” up on the (really very good!) Mortal Engines wiki soon.

The IWOME should be seen as an “in-universe” book, one whose writers don’t know everything (as you’ll see from entries like Anchorage). It’s quite possible they’ve got things wrong. So if the IWOME contradicts the books, the book is the one that has it right.

Relatedly, C is also for the Traction Codex, the little ebook which the IWOME was partly built from. The IWOME uses many parts of the Codex but doesn’t invalidate it – if there’s a direct contradiction, the IWOME takes precedence, but if there’s something mentioned in the Codex but not in the IWOME (Sydney’s cork fenders, for instance) they’re probably still there!

(Oh, and while we’re at it, the short story Traction City Blues in Night Flights supersedes the World Book Day story Traction City. There were some specific requirements for the World Book Day book; this is the short story without them, and is quite a bit closer to the original idea for the story.)

All sorted out? Excellent.

D is for Danundaland

Australia, along with much of sub-Saharan Africa, wasn’t hit as hard in the 60 Minute War as America, Europe or China, although it still suffered heavily from the war’s indirect effects.* Not having quite the same geological upheaval or tempestuous weather, there was no practical reason for Australians to embrace Tractionism – but, when the word reached the continent they did, with enormous enthusiasm.** Much like actual Australia, evolution has led to all sorts of bizarre specialist creatures unknown anywhere else.

Australian cities, from the billabong-dwelling bunyips to the flying-squirrel-like drop-boroughs, are often so heavily adapted as to be unrecognisable to visitors from the Hunting Ground. But as they say on the proud city of Darwin (which regularly reconfigures itself for an advantage over the leaping/burrowing/semi-submersible/intermittently airborne predator towns of the great red interior,) the Australian city is more highly evolved…

A draft map of Danundalund, by Lowtuff

* Nevil Shute’s On the Beach is a disturbing tale of death creeping down to Australia from an apocalyptic war in the Northern Hemisphere, although even the weapons of the Sixty Minute War weren’t as all-destroying as the radiation cloud Shute imagines.

** Having lived in the Outback for a little while I’m not hugely convinced that it would take that much to turn it from a huge, barren expanse full of absurdly large vehicles driven by cheerful sunburnt people into, well…

E is for Exploded Diagrams

One of the things we had in mind when putting together the IWOME were all those interesting Dorling Kindersley visual dictionaries and books of cross-sections. These books show things like a vehicle or a castle, often with cutaways so you can see what’s going on inside, with all the individual parts and their functions labelled.

Doing something like for an entire city is very ambitious, but the hugely talented Philip Varbanov stepped up and created some beautifully detailed illustrations, including the Jenny Haniver and three different stages of London’s history. (And arguably Ian McQue’s gorgeous picture on pages 186-7 is a very exploded London…)

F is for Film

The IWOME is not a film tie-in – it’s based on the books and follows their “canon”. Airships have propellers rather than great big Podracer jets, Engineers are bald and Hester Shaw has one eye. But the people behind the film are very clearly big fans of the series, and (from what we’ve seen!) the world they’ve created is very faithful to that of the books. Hopefully, people who haven’t read the series should still be able to appreciate the IWOME (although they should of course then run off and read the books!).

We also owe some thanks to Peter Jackson, Philippa Boyens, Christian Rivers and all the other people who’ve worked on the film- without it, and all the attention it’s drummed up, the IWOME would probably never have happened. We look forward to seeing it on the big screen!

F is also for Aedel Fakhrie, who has illustrated a variety of things in the IWOME – Old-Tech items and artefacts, vehicles and cities in the IWOME. Aedel hails from Indonesia and owns 17 cats and a cool jacket.

Aedel’s mechanical details, creative city designs and earthy, lived-in colour schemes make for some really distinctive art, and contrast nicely with the black and white cities of Rob Turpin and Philip Varbanov. His Tin Book of Anchorage is fantastically detailed, and his Bunyip is a particularly creepy machine you can absolutely envision roaring unexpectedly out of a billabong (an earlier version with legs was rejected for being slightly too terrifying.)

You can find his Instagram here, his artstation page here and his Twitter here.