With the late 19th century discovery of Germ Theory and the causes of some of the most deadly and infectious diseases of the time, medical science entered a new age. These breakthroughs, made by eminent scientists such as Robert Koch and Louis Pasteur, would be used evermore for the universal benefit of humankind. Yet, the same tools would soon be adapted for another purpose, one that’s often overlooked, but basic to the lives and longevity we enjoy today: the Public Health Movement.

Tenement with Children

With hindsight, it’s not astonishing a concern with public health became prevalent in the late 1800s. At the time there was growing awareness of the physical causes of disease, superseding the belief that illness was a moral problem. Many in the American Public Health Movement would merge bacteriology with their personal experiences treating epidemic disease in a backdrop of overcrowding and filth as Civil War doctors or medics. Add in their experiences with a government agency, the U.S. Sanitary Commission, founded during the war to promote good sanitation, and you have a calling to promote health practices and create government mandates to make them happen.

The most pernicious of the poor sanitary conditions the movement set out to tackle existed in cities, many which created Boards of Health to combat the issue. Wealthy and middle-class city dwellers could already meet health mandates. This left the poor, of whom there were millions, particularly in large centers like New York and Chicago.

Family Living in Attic Apartment

Many were immigrants, attracted to the Land of Opportunity to fill jobs created by the nation’s industrial expansion and growing population. This ingress into America’s urban centers caused non-stop housing shortages wherever a large influx of newcomers stayed to find jobs and kept coming, a situation landlords readily took advantage of. Rents below 14th Avenue in New York skyrocketed, dwarfing what was paid in much nicer areas. To make even more money, landlords subdivided living spaces again and again, making some rooms as tiny as a few feet square. The operation did not take the need for ventilation and sunlight into account, so many of the manufactured rooms had no windows or air circulation, setting up conditions for health problems related to bad air and lack of sunlight.

When tenants, many who did not know English, worked up the nerve to complain, they were told “pay the rent or get out.” They paid the rent. They had no place else to go.

With these dynamics at play, a great number of Manhattan’s immigrant underclass herded into the wards at the tip of the island, an area the more fortunate avoided. Here, and in rundown areas of other cities, the urban poor lived in tenements. In New York, no less than 1,250,000 were jammed into 37,300 of the structures at the end of the 1800s.

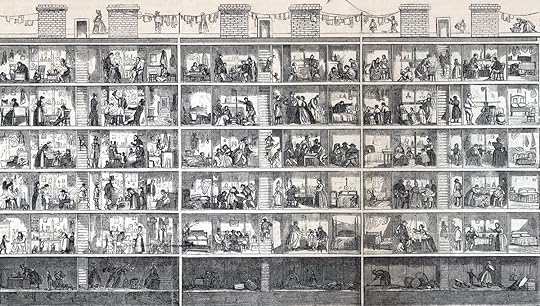

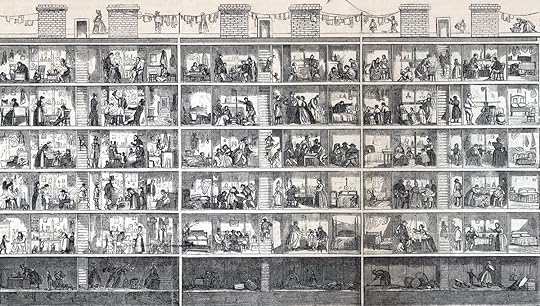

Side Sectional View of Tenement House, 38 Cherry Street, N.Y.

“…what is a tenement?” asked Jacob Riis is his ground-breaking book “The Way the Other Half Lives”, published in 1890. Riis says the legal standard at the time was a building “occupied by three or more families, living independently and doing their cooking on the premises; or by more than two families on a floor, so living and cooking and having a common right in the halls, stairways, yards, etc.” Knowing the defects of these habitations gives a better picture of the living conditions endured in them. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, tenements were widely condemned for lack of light and ventilation, wet cellars, leaky rooves, filthy and inadequate lavatories, small rooms, fire hazards, and immense overcrowding.

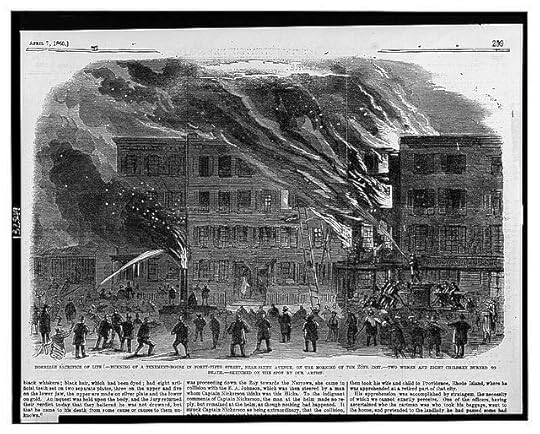

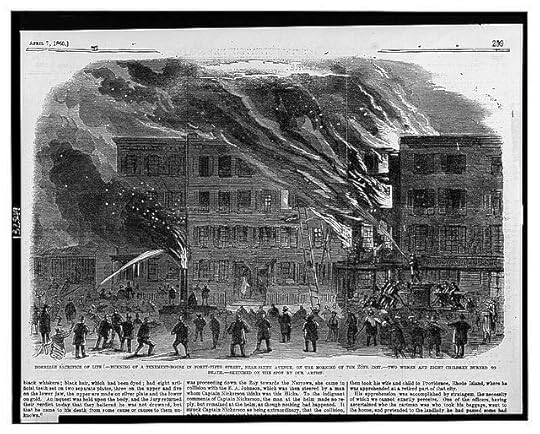

Rear tenements—buildings landlords erected in the space behind the building that fronted the street—were just as harshly condemned for squeezing out the little light and ventilation remaining in already crowded neighborhoods. Sometimes there was no more than a foot clearance between buildings. Such estimates took into account fire escapes, often crammed with articles belonging to the renters inside and posing an obstacle to firemen needing entrance. Little wonder fire was another hazard the authorities bemoaned.

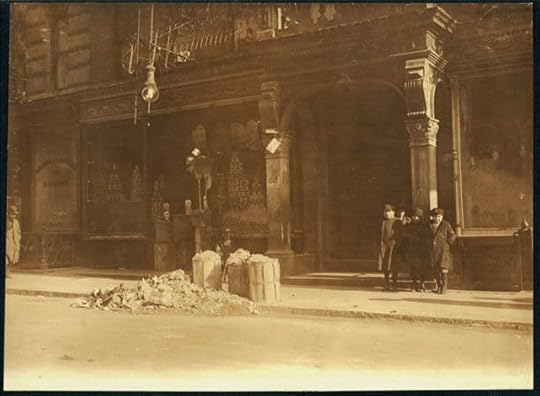

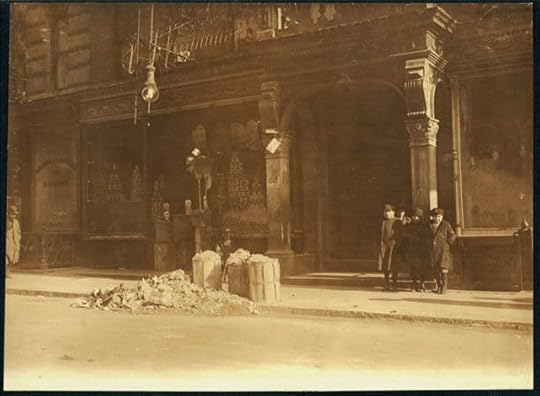

Entrance to McDougal Street Tenements, NYC

Tenement on Fire

You may be relieved to know by the time Riis’s book came out, some of the most noxious features of tenement living had ceased. Early on, the renting of inhabitable cellars had been outlawed, prohibiting both humans and life stock (notably, pigs) from living in these subterranean spaces. But families—sometimes several—might still cram into two- or three-room apartments on any other floor. Nor was it unusual to add a lodger to help meet the rent. Because living spaces sometimes served as a workplace for adults doing clothing or tobacco piecework, children too small to help would be evicted during the day. A none too wholesome alley could become an open playroom for these kids, where many of their pastimes and companions fell short of the National Education Association (NEA) seal of approval.

Children Outside Tenement, NYC

Father Sick in Bed, as Family Carries on Piece Work (NYC, 1912)

The consequences of such deplorable conditions are well recorded. Riis notes that in an infamous tenement called Gotham Court, a cholera epidemic took the lives of 195 out of 1,000 residents. Sanitary department reports from later years record that 10% of Gotham Court inhabitants were taken to the public hospitals every year.

Epidemics in such quarters were fated to travel with a quickness ending too often in death. “Drop a case of scarlet fever, of measles, or of diphtheria into one of these barracks” according to Riis, “and, unless it is caught at the very start and stamped out, the contagion of the one case will sweep block after block and half the people a graveyard.” He shared how Bureau of Vital Statistics maps literally showed the shadow that tenants in poor wards lived under. While disease outbreaks in better areas were only lightly marked on the maps, tenement districts showed a mass of deaths “clearly defined as the track of a tornado”. More than the speed of transmission, Riis noted it was often failure to suitably care for the sick and the foulness of their tenement homes that put many—notably children—in an early grave.

Children Working at Home

This failure came into bold relief in the summer, when rooms lacking air or windows, where children might sleep five or six to a bed, could soar to 115 degrees Fahrenheit. Diarrhea was an especial threat for the youngest at these times.

In the year 1880 a heat blast in mid-June impacted those unable to depart the stifling conditions of the city. Perhaps to the surprise of no one, the death toll for the week of June 19 was 707. Half of this number, 386, were under the age of five, 258 of these dying from “diarrheal diseases”. The death toll continued climbing, and half of the 1038 who died the following week were infants. It continued this way for weeks. The New York Times writer reporting the story seems at pains to reprimand readers: “When it is remembered that over two-thirds of this awful death rate is made up from children under 5 years of age, the results of tenement-house crowding, ignorance of the proper methods of caring for children, unwholesome food and bad water, and above all, impure air, will be fully appreciated.”

No small wonder that infant mortality for some of the most desolate of the tenements could be as high as 50% for infants as young as one year old. Over decades, various locations would build a reputation for such numbers and the poor health of residents. “Typhus Ward”, “Suicide Ward”, and “Lung Block” were appellations only too well describing city blocks or entire wards known as fever dens.

With the invasion of newcomers swelling the density and size of cities to limits never before seen, progressive zeal took on a new urgency. Much of the energy was bent on reducing the appalling numbers of child deaths, driven by the descriptive accounts of newspaper writers, like the one quoted above. It would unfortunately be decades before such sentiments could eradicate routine epidemics for good.

Next month: “The Public Health Movement Takes Action.”

Group of Children, Chrystie Street Tenement, NYC

If you wonder about the Old World life your immigrant ancestors left behind or how people from both sides of the Atlantic came to terms with each other, read Little Italy Diary. Its pages are far more than the history of one man’s family: they are an American history. Available in Amazon.

Little Italy Diary is Angela Edwards' first book. She is also an accomplished poet whose work has been published in Tribeca Poetry Review, Potomac Review, Journal of NJ Poets, Turnings, and other places.Little Italy Diary

newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

Very interesting and informative. I wish Ms Edwards had been my history teacher many years ago....I'm sure I would have been better for it today! Thank you!

Very interesting and informative. I wish Ms Edwards had been my history teacher many years ago....I'm sure I would have been better for it today! Thank you!

What a wonderful piece!!!🙏 I relate with my society, and am glad to have learnt some history from another culture, a problem which still persists in my country

What a wonderful piece!!!🙏 I relate with my society, and am glad to have learnt some history from another culture, a problem which still persists in my country

Modern tenements are now observed as hot beds for the COVID 19 virus outbreaks in many cities. The use of elevators means that many people co-exist in a small space for several minutes and may get exposed to others with the virus.

Modern tenements are now observed as hot beds for the COVID 19 virus outbreaks in many cities. The use of elevators means that many people co-exist in a small space for several minutes and may get exposed to others with the virus.

Very enlightening as to the plight of European immigrants at the turn of the century ! Those infant mortality numbers are so far from where we are now thankfully! This even before the 1918 influenza- frightening!

Very enlightening as to the plight of European immigrants at the turn of the century ! Those infant mortality numbers are so far from where we are now thankfully! This even before the 1918 influenza- frightening!