The Public Health Movement Takes Action

When workers crowding Industrial Age cities fell prey to death and disease at alarming rates, doctors, scientists, and leading citizens set to work solving a medical riddle. Their efforts revealed that poor—or rather, disastrous—living conditions were to blame. The deplorable and overcrowded housing in manufacturing cities were a breeding ground for diseases that infected workers and their families with ease. Near starvation, overwork, and a lack of access to doctors finished them off.

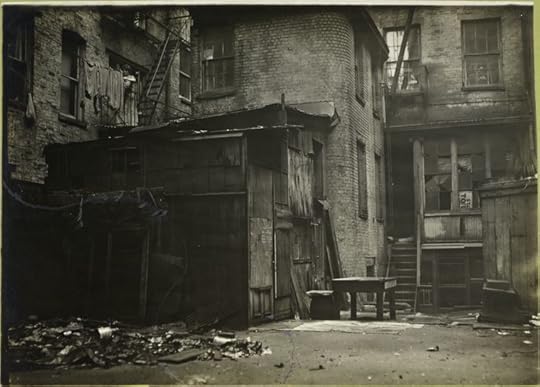

When workers crowding Industrial Age cities fell prey to death and disease at alarming rates, doctors, scientists, and leading citizens set to work solving a medical riddle. Their efforts revealed that poor—or rather, disastrous—living conditions were to blame. The deplorable and overcrowded housing in manufacturing cities were a breeding ground for diseases that infected workers and their families with ease. Near starvation, overwork, and a lack of access to doctors finished them off. Nothing conveys the plight of the early industrial poor so well as the medical workers who tried to help them: “Scenes of filth, crowding, disgusting habits, and drunkenness…whole families sleeping on the floor in one cellar. The children, half-naked, half-starved, and the smell indescribable…” So observed Dr. Henry Gaulter when visiting Manchester, England in 1831-1832 to study the course of a cholera epidemic. (Pictured - Rear of Tenement, Lewis Hine)

Gaulter’s comments revealed a growing awareness that physical conditions—housing, sewerage, water quality, and garbage disposal—can promote or destroy health. This new knowledge and efforts to clean up unsanitary communities came to be known as the Sanitary Movement.

Children Playing Near Dead Horse, NYC (1905)

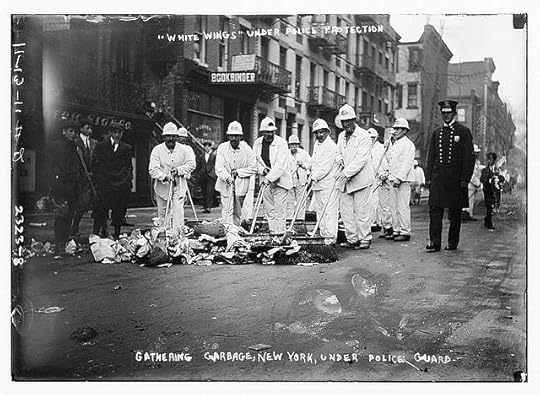

The work of sanitary reformers would not go unnoticed. In 1896, New York City had a parade to celebrate the reforms of George Waring, who created a Street Cleaning Department for the metropolis. With his troop of new city workers, 2.5 million pounds of manure; 40,000 gallons of urine; a sludge of compacted filth; animal carcasses; and standing carts and horses (obstacles to previous efforts) were removed from the streets. Along with setting a new benchmark for urban hygiene, the campaign brought a windfall of smaller benefits—better health for draft animals, the discarding of overshoes, and cleaner venues for children’s play. Most importantly, of course, was the reduction in the death rates among the city’s impoverished that drove the contemporaneous spirit of reform.

George E. Waring, Jr

With acceptance of the Germ Theory of disease in the 1880s, the Sanitary Movement was soon supplanted by the Public Health Movement. Even as sanitary reform rescued the hordes by cleaning their surroundings, Public Health reformers switched the focus to the micro-organisms proven to be solely responsible for the spread of disease, while urging government action to ratify these diseases out of existence.

New York Streetcleaners (1911)

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

Although the United States would lag behind other industrial countries in promoting the new movement, steps in that direction are conspicuous in American newspapers and magazines of the time. Progress was further spurred by a mid-century influx of Irish immigrants and then a later “Atlantic Migration” of Southern and Eastern Europeans into American cities. Yet, for many decades, movement in the area of Public Health was due mostly to the devoted actions of the members of private charities.

Each group chiseled out its area of specialization. The New York Infirmary for Women and Children, for instance, opened in 1859 to “give instructions to poor mothers on the management of infants and the preservation of the health of their families.” The Marine Hospital Service (a federal program) sponsored the National Quarantine Act in 1878 in response to the nation’s growing mobility. And private studies of occupational hazards and diseases lead to new labor laws.

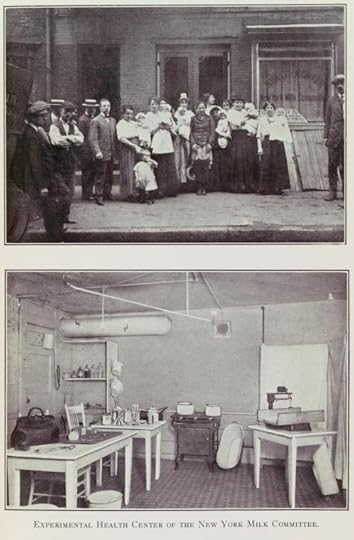

Experimental Center of the NY Milk Committee, 1914

NY Public Library Digital Collections

The creativity and devotion of these voluntary efforts cannot be understated. The New York Infirmary for Women and Children featured the “sanitary visitor,” who traveled to homes of the poor to provide food and supplies, a hand with the baby, and science-based guidance. This contrasts with the Good Samaritan Dispensary, “a very simple consultation center for mothers and infants,” where clients brought themselves to receive the same kind of assistance.

In fact, innovative help given for mothers of newborns, following findings that contaminated milk caused infant deaths, became a cornerstone of Public Health campaigns. “It was recognized that mothers who could not feed their babies naturally should be able to obtain clean cow’s milk at a reasonable price,” says George Rosen in his landmark book A History of Public Health. The resulting “milk stations” that popped up in American cities differed by degrees. All provided clean pasteurized cow’s milk at cost. Some also instructed mothers on the feeding and care of infants, had sterilization facilities on the premises, or offered basic well-infant care. These milk stations were well patronized, as reflected in the reports of philanthropists like Nathan Straus, who gave out 250,000 bottles per month from the milk stations he opened in New York.

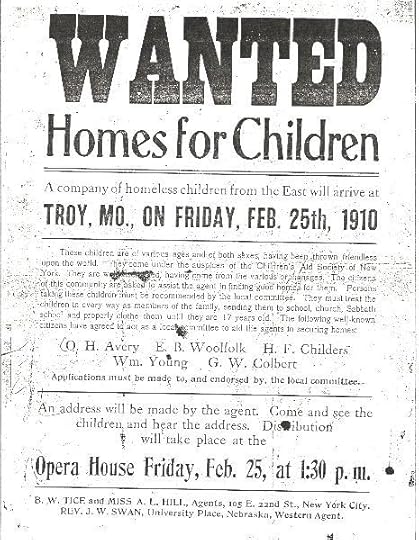

Other private enterprises were in the form of orphans’ homes and organizations to assist youth. The Children’s Aid Society “sheltered…300,000 outcast, homeless, and orphaned children” according to Jacob Riis in How the Other Half Lives. Moreover, the Society “has found homes in the West for 70,000 [children] that had none” he added, referring to the now famous Orphan Train that transplanted homeless youth from city streets to frontier farms. For children whose families were intact, there were Fresh Air funds and summer camps to deliver youngsters (for a while, at least) from the choking air and lurking death of the tenements.

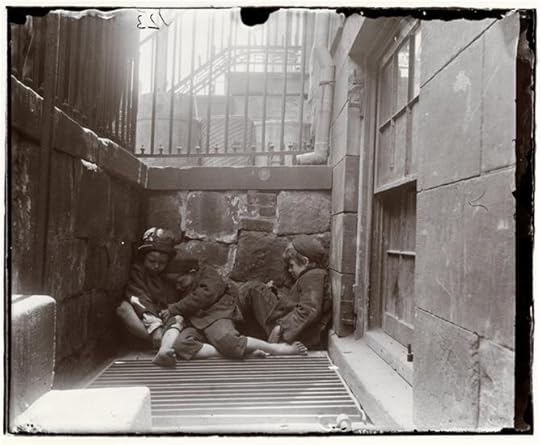

Homeless Children Sleeping on a Grate (1895)

Museum of the City of New York / Jacob Riis

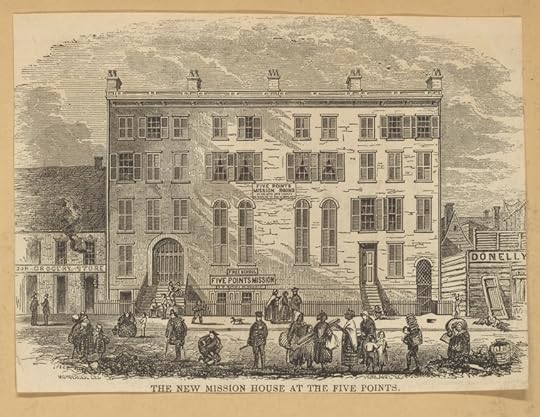

Orphan Train Flyer

This was the era when lodging houses for boys who were tossed out or lost homes due to parental death or incarceration became staples in the American imagination. (Think of the 1938 movie Boys Town.) Such places accepted “toughs” and abandoned street children generally considered to be one step away from the penitentiary or a notorious grave in a Potter’s Field. While such places addressed the child holistically—with a safe bed, meals, vocational training, and religion—these were but soundings for the arch objective of building character, part of which, it was believed, was good hygiene. As said by Riis: “It is the settled belief of the men who run [these lodging houses] that soap and water are as powerful moral agents…as preaching.”

Five Points Mission, NYC

NY Public Library Digital Collections

A great many charitable groups urged new laws or ordinances to redress the deficiencies of tenement living due to overcrowding, insufficient air and light, fire hazards, problems with water supply, poor sanitation, lack of privy and bathing facilities, and inadequate space for children’s play. Some undertook to collect and report violations of existing laws that might have bettered the lives of tenement dwellers, if only the provisions of the laws were followed. Still others set out to educate the public about acceptable health practices of the day—vaccinations, home and personal hygiene, and the effective treatment of disease when it struck.

Children's Aid Society Meal

It was only a matter of time before public sentiment was aroused enough by newspaper and other accounts of the wretched lives of the poor to insist on government action. The trigger for the first tenement law, passed in 1867, was an exhaustive report on conditions in New York City contributing to bad health and substandard living conditions. This was the Council of Hygiene Report, and the law was “…the first legislative action in regard to tenement houses in this country”, according to the “Tenement House Reform in New York” report created in 1900. The act provided for a Metropolitan Board of Health that would in time morph to the Board of Health still serving the city today.

Next: The Government Takes Health Seriously

If you wonder about the Old World life your immigrant ancestors left behind or how people from both sides of the Atlantic came to terms with each other, read Little Italy Diary. Its pages are far more than the history of one man’s family: they are an American history. Available in Amazon.

Little Italy Diary is Angela Edwards' first book. She is also an accomplished poet whose work has been published in Tribeca Poetry Review, Potomac Review, Journal of NJ Poets, Turnings, and other places.

https://www.amazon.com/Little-Italy-D...

Published on November 01, 2020 23:56

•

Tags:

immigrants, italian-american, little-italy, new-york-city

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

message 1:

by

Angela

(new)

Nov 02, 2020 06:42PM

reply

|

flag