Angela Edwards's Blog - Posts Tagged "immigrants"

Which is the Real Little Italy?

When Europeans flooded into the United States from 1880-1920 in what is now called the Great Migration, Little Italys sprang up in locations as diverse as the bustling metropolises of New York and Chicago and small cities like Omaha, Nebraska. The Little Italys from this era, some which continue to thrive, others that are now defunct, are considered by many Italian-Americans to be akin to sacred ground. This is especially true for Italian-Americans whose forebears lived and struggled in these enclaves for years following their arrival.

Mulberry Street, NYC

The largest community of Italians outside Italy lived in New York City during and after the Great Migration. As befitted an important commercial port serving also as the largest gateway for immigration into the country, this boast was not confined to one Italian enclave, but was distributed among several Little Italys. Those with even a passing interest in Manhattan know about the Little Italy at the south end of the island, of Mulberry and Thompson Street fame. Fewer have heard about another celebrated Italian enclave, the Little Italy of the Bronx.

Many will be surprised to learn the more famous Little Italy, the one in Manhattan, has been shrinking for years. With soaring rents and family business buyouts, the delicatessens, butchers, grocers, and restaurants that gave the area its ethnic flavor have been slowly disappearing. What was 50 square blocks of largely Italian-American homes and businesses is now no more than 3 city blocks, hemmed in by Chinatown’s growth. And while 70 years ago half the residents in this Little Italy were Italian-Americans, by 2000 fewer than 6% of residents in the downsized neighborhood identified this way.

Pushcarts, Bronx, NY

Quite a different story for the other Little Italy. That Little Italy, contained in the Belmont neighborhood of the Bronx, had its struggles, but a takeover by a neighboring enclave was not one of them. The Little Italy of the Bronx still has the boundaries set by Italian immigrants that lead to its branding as an Italian neighborhood starting in the late 1800s. Its establishment would lead to a simmering rivalry decades later, and the claim of being the “real Little Italy” all along.

Most immigrants could access the neighborhood only because a 3rd Avenue elevated train line ran through it. Once arrived, they found the area, nestled between Fordham University, the Bronx Zoo, and the borough’s Botanical Gardens, a favorable one for business. Yet, it did not always look as if this Little Italy would be a tourist destination or a fit home for inhabitants, even. During the 1970s the strife in the South Bronx led to an outflow of the European-descended residents of the North Bronx, including this Arthur Avenue-centered neighborhood, and an inflow of Hispanic and African American residents. The demographic shift led banks to believe mortgage lending was an unsafe proposition, and historic Belmont was redlined.

But fate would not give up on an area featured in movies including A Bronx Tale and Marty. After the Bronx recovered from the destructive toll of the 1960s and 70s, a housing resurgence in the 1990s began a new era for the Belmont neighborhood. Its location near major city landmarks continued to be an advantage. And it never lost the attraction of its many Italian family-owned businesses or of being the largest shopping district in the Bronx. An allure so great that in 2016 Arthur Avenue was named one of “America’s Greatest Streets” by the American Planning Association.

Meanwhile, Manhattan’s Little Italy saw the children of its 2nd and 3rd generations leave for the suburbs. From the 1970s on, while its businesses were bought out, the locale was increasingly seen as less an ethnic enclave than a tourist destination.

It was New York’s Italian-American community that saw in this change an opportunity to celebrate Italian-American culture and to educate tourists about the immigrant group’s contributions to America. The idea came on the heels of a 1999 exhibit about Italian Americans in New York attended by 50,000 people at the NY Historical Society. The enormity of the turnout made it clear a great many more visitors could be drawn to a permanent museum for honoring and studying the culture, history, and accomplishments of Italian-Americans. Soon thereafter, the Italian-American Museum (IAM) was founded, led by Museum President Joseph Scelsa. With Manhattan’s Little Italy already a tourist destination, the museum’s initial home on West 44th Street was moved to the former Banca Stabile on the corner of Mulberry and Grand Streets, in what remains of Manhattan’s Little Italy.

It can probably be expected that other Italian-American oriented businesses will follow into Manhattan’s Little Italy as the IAM grows in influence and stature. And it doesn’t look as if Bronx’s Little Italy is going anywhere soon. So the question remains: Which is the real Little Italy? I will leave it for you to decide.

If you wonder about the Old World life your ancestors left behind or how people from both sides of the Atlantic came to terms with each other, read Little Italy Diary. Its pages tell far more than the history of one man’s family: they are an American history. Available in Amazon.

If you wonder about the Old World life your ancestors left behind or how people from both sides of the Atlantic came to terms with each other, read Little Italy Diary. Its pages tell far more than the history of one man’s family: they are an American history. Available in Amazon.

Little Italy Diary is Angela Edwards' first book. She is also an accomplished poet whose work has been published in Tribeca Poetry Review, Potomac Review, Journal of NJ Poets, Turnings, and other places.

Mulberry Street, NYC

The largest community of Italians outside Italy lived in New York City during and after the Great Migration. As befitted an important commercial port serving also as the largest gateway for immigration into the country, this boast was not confined to one Italian enclave, but was distributed among several Little Italys. Those with even a passing interest in Manhattan know about the Little Italy at the south end of the island, of Mulberry and Thompson Street fame. Fewer have heard about another celebrated Italian enclave, the Little Italy of the Bronx.

Many will be surprised to learn the more famous Little Italy, the one in Manhattan, has been shrinking for years. With soaring rents and family business buyouts, the delicatessens, butchers, grocers, and restaurants that gave the area its ethnic flavor have been slowly disappearing. What was 50 square blocks of largely Italian-American homes and businesses is now no more than 3 city blocks, hemmed in by Chinatown’s growth. And while 70 years ago half the residents in this Little Italy were Italian-Americans, by 2000 fewer than 6% of residents in the downsized neighborhood identified this way.

Pushcarts, Bronx, NY

Quite a different story for the other Little Italy. That Little Italy, contained in the Belmont neighborhood of the Bronx, had its struggles, but a takeover by a neighboring enclave was not one of them. The Little Italy of the Bronx still has the boundaries set by Italian immigrants that lead to its branding as an Italian neighborhood starting in the late 1800s. Its establishment would lead to a simmering rivalry decades later, and the claim of being the “real Little Italy” all along.

Most immigrants could access the neighborhood only because a 3rd Avenue elevated train line ran through it. Once arrived, they found the area, nestled between Fordham University, the Bronx Zoo, and the borough’s Botanical Gardens, a favorable one for business. Yet, it did not always look as if this Little Italy would be a tourist destination or a fit home for inhabitants, even. During the 1970s the strife in the South Bronx led to an outflow of the European-descended residents of the North Bronx, including this Arthur Avenue-centered neighborhood, and an inflow of Hispanic and African American residents. The demographic shift led banks to believe mortgage lending was an unsafe proposition, and historic Belmont was redlined.

But fate would not give up on an area featured in movies including A Bronx Tale and Marty. After the Bronx recovered from the destructive toll of the 1960s and 70s, a housing resurgence in the 1990s began a new era for the Belmont neighborhood. Its location near major city landmarks continued to be an advantage. And it never lost the attraction of its many Italian family-owned businesses or of being the largest shopping district in the Bronx. An allure so great that in 2016 Arthur Avenue was named one of “America’s Greatest Streets” by the American Planning Association.

Meanwhile, Manhattan’s Little Italy saw the children of its 2nd and 3rd generations leave for the suburbs. From the 1970s on, while its businesses were bought out, the locale was increasingly seen as less an ethnic enclave than a tourist destination.

It was New York’s Italian-American community that saw in this change an opportunity to celebrate Italian-American culture and to educate tourists about the immigrant group’s contributions to America. The idea came on the heels of a 1999 exhibit about Italian Americans in New York attended by 50,000 people at the NY Historical Society. The enormity of the turnout made it clear a great many more visitors could be drawn to a permanent museum for honoring and studying the culture, history, and accomplishments of Italian-Americans. Soon thereafter, the Italian-American Museum (IAM) was founded, led by Museum President Joseph Scelsa. With Manhattan’s Little Italy already a tourist destination, the museum’s initial home on West 44th Street was moved to the former Banca Stabile on the corner of Mulberry and Grand Streets, in what remains of Manhattan’s Little Italy.

It can probably be expected that other Italian-American oriented businesses will follow into Manhattan’s Little Italy as the IAM grows in influence and stature. And it doesn’t look as if Bronx’s Little Italy is going anywhere soon. So the question remains: Which is the real Little Italy? I will leave it for you to decide.

If you wonder about the Old World life your ancestors left behind or how people from both sides of the Atlantic came to terms with each other, read Little Italy Diary. Its pages tell far more than the history of one man’s family: they are an American history. Available in Amazon.

If you wonder about the Old World life your ancestors left behind or how people from both sides of the Atlantic came to terms with each other, read Little Italy Diary. Its pages tell far more than the history of one man’s family: they are an American history. Available in Amazon.Little Italy Diary is Angela Edwards' first book. She is also an accomplished poet whose work has been published in Tribeca Poetry Review, Potomac Review, Journal of NJ Poets, Turnings, and other places.

Published on February 09, 2020 13:32

•

Tags:

immigrants, italian-american, little-italy, new-york-city

THE WITCHES OF NEW YORK

Where it comes to witchcraft, most of us are more likely to think of Salem, Massachusetts, than New York, New York. But the truth is, some form of folk magic has been practiced in most of the United States, with a surprising amount in the cities. For the metropolis has always held an attraction for the immigrant, who carries luggage, but also the practices of his or her homeland.

Italian immigrants have had a presence in New York City that predates the Great Migration of 1880-1920. Along with pasta, large funerals, and devoted families, they introduced the Italian strega (witch) to lower Manhattan, Italian Harlem, and every corner of the city.

Herbalist and folk healer, holy person and spell caster, keeper of intimate secrets, the strega's life must have been the stuff of melodrama. Those who dealt in black magic might cast spells to bring bad luck, ill health, or ruined relationships to others. Yet, little to no attention was paid to the enigmatic figure of the witch, who could be male or female, until relatively late in the Italian American experience.

Witches from the Medieval Period

Charlotte Chapman was an American who resided and studied life in a Sicilian village for 18 months in the late 1920's. From her work, "Milocca: a Sicilian Village", we learn that belief in witchcraft and spirits was typical in Sicily's small towns and villages. Traditional magic, according to Chapman, was often passed down in families, with details of spells and incantations kept secret. This generational secrecy could partly account for the reticence of Italians on the subject of the craft. But in this country, the silence was equally due to efforts throughout the U.S. to assimilate newcomers by pushing "superstitious" practices underground, where progressives thought they belonged. As a result, folk magic was extinguished in many Italian American families, carefully hidden in others.

It was the grandchildren and great-grandchildren of the earlier immigrants who would revive and try to make these folk beliefs their own. To this end, some of them adopted Stregheria, a version of Italian folk magic popularized by author and lecturer Raven Grimassi. While branded as traditional magic by Grimassi and devotees, many have said Stregheria is closer to the neopagan witchcraft religion, Wicca.

Margaret Murray

The source for both practices was Margaret Murray's sentinel publication, "The Witch Cult of Western Europe", a book that identified certain pagan practices as the remnant of an ancient religion and shaped our ideas about witchcraft today. But while both Stregheria and Wicca have significant followers, critics say that neither is an authentic form of witchcraft. More ironic still is that at the same time Murray's book was released, millions of true believers of witchcraft and the occult were entering the U.S. in record numbers, only to find their traditional ideas denigrated.

The book was released in 1921, a time when archeological finds--like the intact burial chamber of Egyptian King Tutankhamun in 1922--were rewriting history, and revelations about the cultures behind the discoveries were part of the daily media diet. But while the age was curious about the ancients, living survivors of Murray's witch cult found themselves in hot water where it came to putting their beliefs into practice.

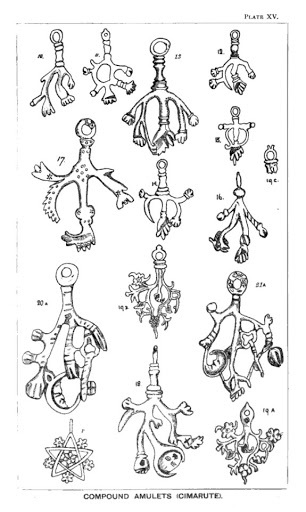

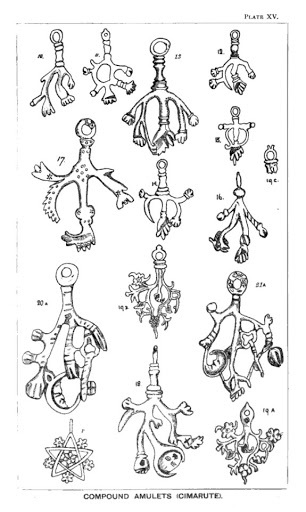

Witch's Charms

The stand-off becomes clear in newspapers of the time. In one story, readers are told: "In the New York Italian District, some Sicilians are said to believe in magic jewelry." A New York Times article claims "The East Side Still Has its Witches", then goes on to say a Mrs. Carmen Rubino scammed a woman into paying $370.00 to get rid of a long list of predicted ills and adversities, including herself of stomach troubles, her house of devils, and her son of a murder rap. When Rubino was finally hauled into court, the magistrate remarked: "Now I understand why they used to burn witches."

Yet, it would be patently untrue to say every witch in the Italian American community was a con artist. Chapman records that some witches in Milocca refused money or payment of any kind for their services. Other sources say the Old World witch often performed good works only to raise his or her reputation and prestige in the community at large.

Perhaps proof of the beneficence of the traditional Italian witch lies in their tendency to become midwives here in America. Indeed, the very resurgence of the witch from the 1960s onward seems to disclose an essential need, here in the West, at least, for someone to fill the role. And while their actions may not ring true to some, it could be said those practicing Stregheria, and Wicca, too, are authentic in that they embrace ancient forms in defiance of an increasingly modern world. It's an attitude I believe would be approved by those emigree witches of long ago.

Little Italy Diary

If you wonder about the Old World life your immigrant ancestors left behind or how people from both sides of the Atlantic came to terms with each other, read Little Italy Diary. Its pages tell far more than the history of one man’s family: they are an American history. Available in Amazon.

Little Italy Diary is Angela Edwards' first book. She is also an accomplished poet whose work has been published in Tribeca Poetry Review, Potomac Review, Journal of NJ Poets, Turnings, and other places.

Italian immigrants have had a presence in New York City that predates the Great Migration of 1880-1920. Along with pasta, large funerals, and devoted families, they introduced the Italian strega (witch) to lower Manhattan, Italian Harlem, and every corner of the city.

Herbalist and folk healer, holy person and spell caster, keeper of intimate secrets, the strega's life must have been the stuff of melodrama. Those who dealt in black magic might cast spells to bring bad luck, ill health, or ruined relationships to others. Yet, little to no attention was paid to the enigmatic figure of the witch, who could be male or female, until relatively late in the Italian American experience.

Witches from the Medieval Period

Charlotte Chapman was an American who resided and studied life in a Sicilian village for 18 months in the late 1920's. From her work, "Milocca: a Sicilian Village", we learn that belief in witchcraft and spirits was typical in Sicily's small towns and villages. Traditional magic, according to Chapman, was often passed down in families, with details of spells and incantations kept secret. This generational secrecy could partly account for the reticence of Italians on the subject of the craft. But in this country, the silence was equally due to efforts throughout the U.S. to assimilate newcomers by pushing "superstitious" practices underground, where progressives thought they belonged. As a result, folk magic was extinguished in many Italian American families, carefully hidden in others.

It was the grandchildren and great-grandchildren of the earlier immigrants who would revive and try to make these folk beliefs their own. To this end, some of them adopted Stregheria, a version of Italian folk magic popularized by author and lecturer Raven Grimassi. While branded as traditional magic by Grimassi and devotees, many have said Stregheria is closer to the neopagan witchcraft religion, Wicca.

Margaret Murray

The source for both practices was Margaret Murray's sentinel publication, "The Witch Cult of Western Europe", a book that identified certain pagan practices as the remnant of an ancient religion and shaped our ideas about witchcraft today. But while both Stregheria and Wicca have significant followers, critics say that neither is an authentic form of witchcraft. More ironic still is that at the same time Murray's book was released, millions of true believers of witchcraft and the occult were entering the U.S. in record numbers, only to find their traditional ideas denigrated.

The book was released in 1921, a time when archeological finds--like the intact burial chamber of Egyptian King Tutankhamun in 1922--were rewriting history, and revelations about the cultures behind the discoveries were part of the daily media diet. But while the age was curious about the ancients, living survivors of Murray's witch cult found themselves in hot water where it came to putting their beliefs into practice.

Witch's Charms

The stand-off becomes clear in newspapers of the time. In one story, readers are told: "In the New York Italian District, some Sicilians are said to believe in magic jewelry." A New York Times article claims "The East Side Still Has its Witches", then goes on to say a Mrs. Carmen Rubino scammed a woman into paying $370.00 to get rid of a long list of predicted ills and adversities, including herself of stomach troubles, her house of devils, and her son of a murder rap. When Rubino was finally hauled into court, the magistrate remarked: "Now I understand why they used to burn witches."

Yet, it would be patently untrue to say every witch in the Italian American community was a con artist. Chapman records that some witches in Milocca refused money or payment of any kind for their services. Other sources say the Old World witch often performed good works only to raise his or her reputation and prestige in the community at large.

Perhaps proof of the beneficence of the traditional Italian witch lies in their tendency to become midwives here in America. Indeed, the very resurgence of the witch from the 1960s onward seems to disclose an essential need, here in the West, at least, for someone to fill the role. And while their actions may not ring true to some, it could be said those practicing Stregheria, and Wicca, too, are authentic in that they embrace ancient forms in defiance of an increasingly modern world. It's an attitude I believe would be approved by those emigree witches of long ago.

Little Italy Diary

If you wonder about the Old World life your immigrant ancestors left behind or how people from both sides of the Atlantic came to terms with each other, read Little Italy Diary. Its pages tell far more than the history of one man’s family: they are an American history. Available in Amazon.

Little Italy Diary is Angela Edwards' first book. She is also an accomplished poet whose work has been published in Tribeca Poetry Review, Potomac Review, Journal of NJ Poets, Turnings, and other places.

Published on March 15, 2020 10:51

•

Tags:

immigrants, immigration, italian-american, margaret-murray, raven-grimassi, strega, stregheria

The Public Health Movement Takes Action

When workers crowding Industrial Age cities fell prey to death and disease at alarming rates, doctors, scientists, and leading citizens set to work solving a medical riddle. Their efforts revealed that poor—or rather, disastrous—living conditions were to blame. The deplorable and overcrowded housing in manufacturing cities were a breeding ground for diseases that infected workers and their families with ease. Near starvation, overwork, and a lack of access to doctors finished them off.

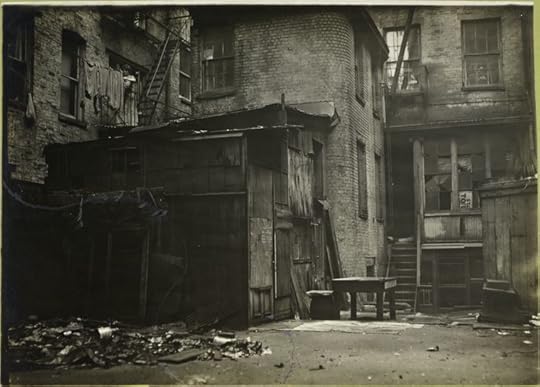

When workers crowding Industrial Age cities fell prey to death and disease at alarming rates, doctors, scientists, and leading citizens set to work solving a medical riddle. Their efforts revealed that poor—or rather, disastrous—living conditions were to blame. The deplorable and overcrowded housing in manufacturing cities were a breeding ground for diseases that infected workers and their families with ease. Near starvation, overwork, and a lack of access to doctors finished them off. Nothing conveys the plight of the early industrial poor so well as the medical workers who tried to help them: “Scenes of filth, crowding, disgusting habits, and drunkenness…whole families sleeping on the floor in one cellar. The children, half-naked, half-starved, and the smell indescribable…” So observed Dr. Henry Gaulter when visiting Manchester, England in 1831-1832 to study the course of a cholera epidemic. (Pictured - Rear of Tenement, Lewis Hine)

Gaulter’s comments revealed a growing awareness that physical conditions—housing, sewerage, water quality, and garbage disposal—can promote or destroy health. This new knowledge and efforts to clean up unsanitary communities came to be known as the Sanitary Movement.

Children Playing Near Dead Horse, NYC (1905)

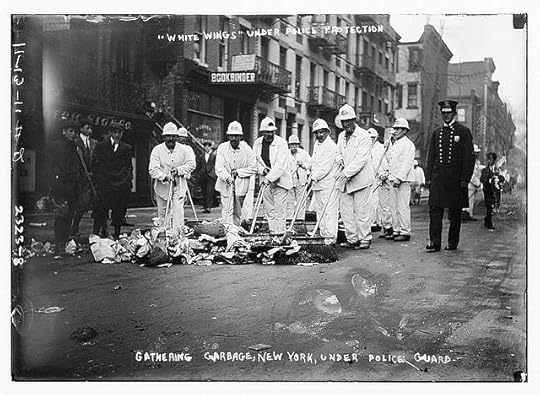

The work of sanitary reformers would not go unnoticed. In 1896, New York City had a parade to celebrate the reforms of George Waring, who created a Street Cleaning Department for the metropolis. With his troop of new city workers, 2.5 million pounds of manure; 40,000 gallons of urine; a sludge of compacted filth; animal carcasses; and standing carts and horses (obstacles to previous efforts) were removed from the streets. Along with setting a new benchmark for urban hygiene, the campaign brought a windfall of smaller benefits—better health for draft animals, the discarding of overshoes, and cleaner venues for children’s play. Most importantly, of course, was the reduction in the death rates among the city’s impoverished that drove the contemporaneous spirit of reform.

George E. Waring, Jr

With acceptance of the Germ Theory of disease in the 1880s, the Sanitary Movement was soon supplanted by the Public Health Movement. Even as sanitary reform rescued the hordes by cleaning their surroundings, Public Health reformers switched the focus to the micro-organisms proven to be solely responsible for the spread of disease, while urging government action to ratify these diseases out of existence.

New York Streetcleaners (1911)

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

Although the United States would lag behind other industrial countries in promoting the new movement, steps in that direction are conspicuous in American newspapers and magazines of the time. Progress was further spurred by a mid-century influx of Irish immigrants and then a later “Atlantic Migration” of Southern and Eastern Europeans into American cities. Yet, for many decades, movement in the area of Public Health was due mostly to the devoted actions of the members of private charities.

Each group chiseled out its area of specialization. The New York Infirmary for Women and Children, for instance, opened in 1859 to “give instructions to poor mothers on the management of infants and the preservation of the health of their families.” The Marine Hospital Service (a federal program) sponsored the National Quarantine Act in 1878 in response to the nation’s growing mobility. And private studies of occupational hazards and diseases lead to new labor laws.

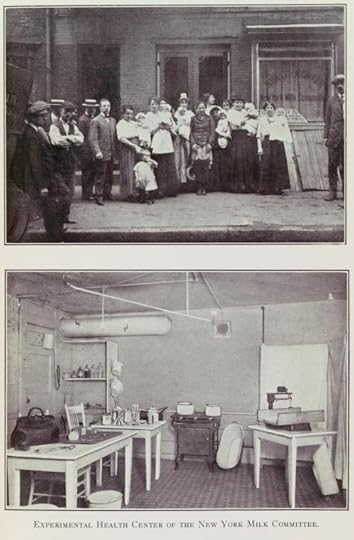

Experimental Center of the NY Milk Committee, 1914

NY Public Library Digital Collections

The creativity and devotion of these voluntary efforts cannot be understated. The New York Infirmary for Women and Children featured the “sanitary visitor,” who traveled to homes of the poor to provide food and supplies, a hand with the baby, and science-based guidance. This contrasts with the Good Samaritan Dispensary, “a very simple consultation center for mothers and infants,” where clients brought themselves to receive the same kind of assistance.

In fact, innovative help given for mothers of newborns, following findings that contaminated milk caused infant deaths, became a cornerstone of Public Health campaigns. “It was recognized that mothers who could not feed their babies naturally should be able to obtain clean cow’s milk at a reasonable price,” says George Rosen in his landmark book A History of Public Health. The resulting “milk stations” that popped up in American cities differed by degrees. All provided clean pasteurized cow’s milk at cost. Some also instructed mothers on the feeding and care of infants, had sterilization facilities on the premises, or offered basic well-infant care. These milk stations were well patronized, as reflected in the reports of philanthropists like Nathan Straus, who gave out 250,000 bottles per month from the milk stations he opened in New York.

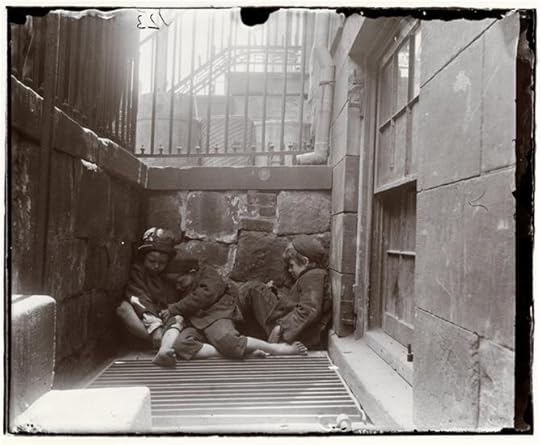

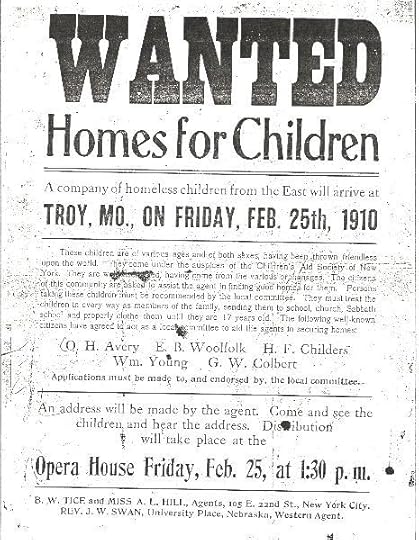

Other private enterprises were in the form of orphans’ homes and organizations to assist youth. The Children’s Aid Society “sheltered…300,000 outcast, homeless, and orphaned children” according to Jacob Riis in How the Other Half Lives. Moreover, the Society “has found homes in the West for 70,000 [children] that had none” he added, referring to the now famous Orphan Train that transplanted homeless youth from city streets to frontier farms. For children whose families were intact, there were Fresh Air funds and summer camps to deliver youngsters (for a while, at least) from the choking air and lurking death of the tenements.

Homeless Children Sleeping on a Grate (1895)

Museum of the City of New York / Jacob Riis

Orphan Train Flyer

This was the era when lodging houses for boys who were tossed out or lost homes due to parental death or incarceration became staples in the American imagination. (Think of the 1938 movie Boys Town.) Such places accepted “toughs” and abandoned street children generally considered to be one step away from the penitentiary or a notorious grave in a Potter’s Field. While such places addressed the child holistically—with a safe bed, meals, vocational training, and religion—these were but soundings for the arch objective of building character, part of which, it was believed, was good hygiene. As said by Riis: “It is the settled belief of the men who run [these lodging houses] that soap and water are as powerful moral agents…as preaching.”

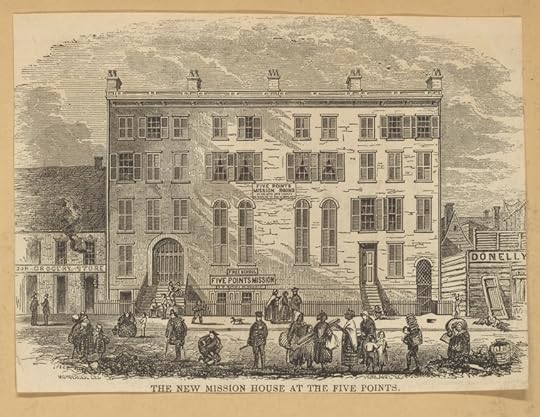

Five Points Mission, NYC

NY Public Library Digital Collections

A great many charitable groups urged new laws or ordinances to redress the deficiencies of tenement living due to overcrowding, insufficient air and light, fire hazards, problems with water supply, poor sanitation, lack of privy and bathing facilities, and inadequate space for children’s play. Some undertook to collect and report violations of existing laws that might have bettered the lives of tenement dwellers, if only the provisions of the laws were followed. Still others set out to educate the public about acceptable health practices of the day—vaccinations, home and personal hygiene, and the effective treatment of disease when it struck.

Children's Aid Society Meal

It was only a matter of time before public sentiment was aroused enough by newspaper and other accounts of the wretched lives of the poor to insist on government action. The trigger for the first tenement law, passed in 1867, was an exhaustive report on conditions in New York City contributing to bad health and substandard living conditions. This was the Council of Hygiene Report, and the law was “…the first legislative action in regard to tenement houses in this country”, according to the “Tenement House Reform in New York” report created in 1900. The act provided for a Metropolitan Board of Health that would in time morph to the Board of Health still serving the city today.

Next: The Government Takes Health Seriously

If you wonder about the Old World life your immigrant ancestors left behind or how people from both sides of the Atlantic came to terms with each other, read Little Italy Diary. Its pages are far more than the history of one man’s family: they are an American history. Available in Amazon.

Little Italy Diary is Angela Edwards' first book. She is also an accomplished poet whose work has been published in Tribeca Poetry Review, Potomac Review, Journal of NJ Poets, Turnings, and other places.

https://www.amazon.com/Little-Italy-D...

Published on November 01, 2020 23:56

•

Tags:

immigrants, italian-american, little-italy, new-york-city