On the Four Table Legs of Traveller, Leg 1:

Mortgages

Mongoose Traveller’s starship mortgage-payment-system

is the most brilliant game mechanic I’ve ever encountered, as a DM. It’s also the

first rule I’d ignore if I wasn’t consciously trying to play the game exactly

how it’s described in the book.

I’ve been

involved in two Traveller campaigns

in the past as a player (both with the same DM), and am currently DMing a

third. All of them are using Mongoose’s first edition. I’ve never played any

other edition of traveller, and know almost nothing about the history of the

game. I don’t know which mechanics are unique to this edition of Traveller and which

have been around for decades.

In the

campaigns in which I was a player, I think the DM was continually frustrated

with the rules of the game. He wanted to run a tight, story-focused campaign

and picked up Traveller assuming it would be, essentially, D&D in space. For

his second campaign, he chopped out huge chunks of the ruleset and replaced it

with homebrew ones, removing space travel and Traveller’s quirky character

creation entirely. This worked for the game he wanted to run (he’s an extraordinarily

talented DM), but I think we all came away feeling pretty lukewarm about the

actual rules.

Bored out

of my mind in lockdown, desperate for anything to shake up the daily routine, I

picked up the copy of Traveller

that had been sitting on my bookshelf, untouched, and skimmed through it. In a

mood of “I’ll humour this weird rulebook,” I followed the random

subsector creation chapter to the letter,

creating a surprisingly-well fleshed out chunk of space to play around in.

It was then that I realized I’d never actually played Traveller. So I dragged my partner along

in an experiment: let’s play Traveller,

exactly how it is described in the book, no matter how flat-out insane the

rules seem to be. I will only consider houseruling or changing a rule once

we’ve both figured out what it’s for. I learned a ton in this experiment, so, during my kid’s naps (oh, right, I have

a daughter now, that’s where I disappeared to, Internet), I’ll write about what

I’ve learned.

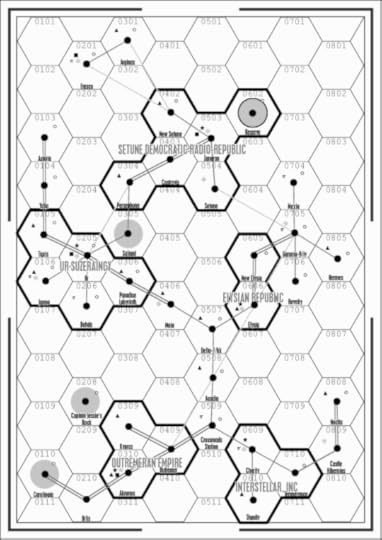

(The Carlia Subsector.

Not pictured: along with this map is a LONG word document describing the

atmosphere, gravity, population, tech level, cultural quirks, government, etc.

of the main world in each of these systems, plus a huge table of the price of

dozens of trade goods on each planet. These, it turns out, are crucial game

aids. I’ll get into them later.)

Traveller, I’ve learned, is a table held up by four

legs: Finances, Character Creation, Patrons, and Random Encounters. If you

remove any of these legs, the rest of

the game stops working. Following

them, as described, gives you a rip-roaring swashbuckling adventure of fighting

pirates, escaping bounty hunters, smuggling, jailbreaks, and all that good

stuff you want in a campaign—but it happens spontaneously.

I’ll get into it more in detail, but for now, we’re going to talk about finances

in Traveller.

Mortgage Payments

The central

driving mechanic of Traveller is

making mortgage payments for your starship. The assumption is that the player

characters are part-owners of an FTL-capable starship that’s more expensive

than any one person, or any ten people, could ever afford outright. The game

(thankfully) provides a quick way to calculate your starship’s mortgage

payments (something like the value of the ship/240 per month), and for all of

the example ships in the book, gives them to you pre-calculated. In the case of

my solo campaign, my partner owed the bank a whopping 500,000 credits a month

for her Corsair. For scale, that’s the exact

same price as

the single most powerful gun in the game (the “Fusion Gun, Man

Portable”), owed monthly. In

D&D terms, she had to raise the equivalent of a +5 Longsword every. Single. Month.

(In addition to mortgage payments are smaller fees: life

support (i.e., food and water), crew salaries, fuel, and ship maintenance, but

the mortgage is by far the largest single expense, so that’s what I’ll focus on).

I started

my partner out with a fueled up and fully-crewed ship (we used pre-generated

NPC stats from the middle of the book for her crew, plus an NPC who was

generated during her character creation, which I’ll get into later). Character

creation started her with 10,000 credits, and I told her she had until the end

of the month to multiply that by fifty times.

The fastest

way by far in Traveller to make money

is to interact with the very well fleshed-out trade rules. Each spaceship has a

certain amount of tons of cargo it can carry, and each world has a list of

trade goods for sale at various prices. So the clear way to raise that 500

grand was to speculatively buy trade goods, pick up passengers and freight,

deliver mail, and so on. These rules are generous;

by stacking modifiers, it’s possible to reliably quadruple your principal every

time you reach a new planet (which happens every week).

I think my

old DM severely nerfed the trade rules (he also didn’t enforce mortgage

payments, leaving them on the cutting room floor like D&D’s Encumbrance

rules) due to this seemingly-unbalanced generosity. Again: the best gun in the

game is 500,000 credits—so how on earth can a system that lets you make

hundreds, even millions, of credits by trading stand?

Well, it

turns out, the bank simply taking 95% of your player’s earnings every month

severely dampens potentially-snowballing nonlinear growth, so my partner and I

never saw the kind of wealth explosion that looks inevitable from the rules as

written, despite her scraping together everything she could do maximize profits.

In all the time we’ve been playing, despite having already made millions of

credits, she actually hasn’t been able to buy a gun better than her starting

laser pistol, or, in fact, any armour at all. I’ll get to why in a moment,

because the most important thing about the trade system is that…

Garden

worlds sell cheap food. High-population worlds buy food for a high price.

High-population worlds sell manufactured goods that are in high-demand on

non-industrial worlds, and so on. In a quest to maximize profits, the party was

locked into a continual tour of the subsector I generated earlier, constantly

moving from place to place. Staying put for any length of time meant letting

time trickle away (time that could be

spent raking in cash for crippling mortgage payments), so that wasn’t an

option. What wound up happening was that the party went on a self-guided tour

of the subsector, stopping in at colourful worlds I’d generated earlier. This

happened entirely without me, as DM, having to dangle bait in front of the party

the way that I always have to in D&D. Travel is good, because…

I’ve

already spoken at length on the subject of random encounters [here], but Traveller really builds the game around

random tables in an elegant way. Every time the party jumps from one world to

another, there’s a chance they’ll get waylaid by pirates (the rulebook has a

fun, albeit hidden, ‘pirate table’ that describes different tricks and hijinks

that pirates use to attack). 'Pirates’ in Traveller

are spaceship owners unable to pay their mortgages by legitimate means, so turn

to piracy. The fact that the party is always

carrying their life savings in trade commodities whenever they travel around

makes them a prime target for piracy, and leads to combat with stakes beyond

“fight till everyone’s dead.” The pirates aren’t orcs, and don’t want

to kill the players for no reason. They want to take their cargo and get away

as quickly as possible, suffering the least damage as possible, and the players

want the opposite. Thus: pre-combat negotiations, tricks, hijinks (my partner,

carrying a cargo of “domestic goods,” chose to have her crew throw

individual toasters out of the cargo bay each in different directions to ensure

that the pirates had to engage in lengthy EVA-missions to catch them each, thus

allowing her ship to escape without suffering damage).

Traveller’s starship battle rules are fun (and integrate

into boarding actions that results in player-scale combat), and are triggered primarily just by moving around.

Conflict is fun by itself (that’s why combat rules are most of the rules in most games), but in this context, have the

added advantage, as…

Tradeoffs

It became

clear to my partner after her first run-in with pirates that her ship and crew

were under-gunned. While buying powerful weapons and armour is trivially cheap

compared to the amount of money she was raking in through trade (most weapons

cap out at a few thousand credits, and she was moving hundreds of thousands a

week), actually getting her hands on some was another matter.

Good

weapons in Traveller are advanced

ones, which have a high-TL (tech level) rating. These weapons are only

available on high-TL worlds (each world has a TL rating generated in subsector

generation). Making a detour from trading to buy 'adventuring equipment’ wound

up being an extremely costly endeavour,

taking the party weeks out of the way of the most profitable trade route. The closest

world in which these weapons exist also outlaws all weapons (various laws are

generated procedurally as well) which means engaging in black market smuggling

(which is fleshed out in the rules) and risks run-ins with the law.

Compounding

this problem was that her Corsair took minor damage in the combat with the

pirates, and the nearest world with a shipyard capable of repairing the ship was

different from, and out of the way of, the high tech world with fancy fusion

guns. Also, getting the ship repaired meant that it would be in drydock for

days or even weeks, which incurs an opportunity cost of almost a million

credits that could have been made during trade…

In her

case, she wound up getting her ship repaired, forgoing arming herself and her

crew, and skirting dangerously close to bankruptcy kicking her heels as her

ship was patched up. There isn’t an easy answer to what she 'ought’ to have

done, which was fun as hell. Further,

as a DM, I wasn’t annoyed that she was 'messing up the plot’ by staying put (or

frustrated that she wasn’t going to my elaborately-plotted narrative that would

occur when she tried to buy black market weapons) because there was no plot. Everything that came about

emerged procedurally.

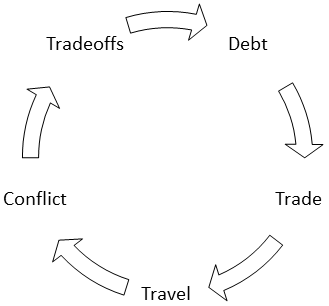

The beating

heart of a Traveller sandbox

campaign is this loop:

Without DM

intervention (or Patrons, which are sort of procedurally-generated adventure

hooks), this loop can sustain a campaign pretty much indefinitely. What this

means as a DM is that any DM-interventions (i.e., adding in pre-written

adventure hooks or encounters or whatever) can be attached to any of these

steps to allow it to come about during play. It also means that if you don’t have any pre-scripted content (to choose

an example completely at random, let’s just say your hypothetical one-year-old

threw your notes in a toilet) you can just sit back and let the loop above take

care of providing entertainment.

To bring

this back to mortgages, if your players don’t have the threat of having their

spaceship repossessed by the bank hanging over them like the Doom of Damocles,

then the whole system breaks down, and the DM has to do all the heavy lifting

of providing character motivation to go explore new planets.

Next, we’ll

talk about how Traveller’s patron

system ties into all of this.

Sir Poley's Blog

- Sir Poley's profile

- 21 followers