Gully Foyle: The Best Science-Fiction Comic You Never Read - Part 1

The following is a revised and updated version of the article I originally wrote for the long-expired PulpFaction.net website back in 2007. Since then, the full story behind the “lost” comic-strip adaptation of Alfred Bester’s SF novel, The Stars My Destination, has been told in even greater depth by Daniel Best on his 20thCentury Danny Boy blog. But my intention has been, for many years now, to republish my original account of Stanley and Reginald Pitt’s lost comic-strip masterpiece, Gully Foyle. I hope you will enjoy discovering this fascinating fragment of Australian comics history.

The Pulp Apprentice

Alfred Bester

Alfred BesterAlfred Bester (1913-1987) was born and raised in New York City, and studied at University of Pennsylvania in the mid-1930s. He briefly attended Columbia Law School, but dropped out to begin his professional writing career in public relations in the late 1930s. He wrote his first short story, “The Broken Axiom”, for the April 1939 edition of Thrilling Wond er Stories , but it wasn’t until the early 1950s when he honed his distinctive style and, in doing so, demonstrated just how far the boundaries of science-fiction literature could be stretched.

Bester’s writing apprenticeship began just as the pulp magazines he wrote for were losing ground to the meteoric rise of America’s comic book industry. Far from spelling the end of his embryonic career, comic books provided a valuable – and lucrative – training ground for Bester throughout the 1940s. He wrote several scripts for Fawcett Publications’ Captain Marvel Adventures, but spent most of the decade working for DC Comics, penning the adventures of ‘Genius Jones’ and ‘Starman’ for Adventure Comics, and writing stories for Green Lantern’s self-titled comic magazine (For many years, it was widely believed that Bester composed Green Lantern’s famous oath, but he refuted this claim decades later).

Bester also worked as a “ghost writer” for Lee Falk, creator of the popular newspaper comic strips, Mandrake the Magician and The Phantom, during the mid-1940s, while Falk served as radio director for the Office of War Information’s foreign-language division during World War Two (Bester is credited with writing the 1943 Phantom storyline, “Bent Beak Broder”, which introduced the Phantom’s civilian alter ego, ‘Mr. Walker’, and established the popular ‘Old Jungle Sayings’ script device, which has remained in use with The Phantomcomic strip ever since).

In 1936, Bester married Rolly Goulko (1917-1984), a successful radio and television actor, who later became casting director with the New York advertising agency, Ted Bates & Company. She told her husband that the producers of the radio serial, Nick Carter, Master Detective, were seeking script submissions. Bester wrote four episodes of the series, which were aired by the Mutual Broadcasting System throughout 1944-46.

He continued writing science-fiction stories for American “pulp magazines” throughout the 1940s, including Astounding Science Fiction, Astonishing Stories, and Unknown Worlds. His first published novel, however, had nothing to do with science fiction. Who He? was a satirical exposé of America’s television industry, told from the perspective of an alcoholic gameshow writer. The novel was originally published by Dial Press in 1953 and renamed The Rat Race for its paperback release by Berkley Books in 1955.

He continued writing science-fiction stories for American “pulp magazines” throughout the 1940s, including Astounding Science Fiction, Astonishing Stories, and Unknown Worlds. His first published novel, however, had nothing to do with science fiction. Who He? was a satirical exposé of America’s television industry, told from the perspective of an alcoholic gameshow writer. The novel was originally published by Dial Press in 1953 and renamed The Rat Race for its paperback release by Berkley Books in 1955. The Demolished Man

By the early 1950s, Bester had established himself as a successful and popular writer, renowned for his original and imaginative work in comics, magazines, radio, and television. But his greatest literary achievements took shape in the pages of the science-fiction “pulps” where he began his career more than a decade ago.

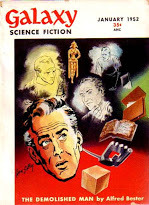

Bester’s debut science-fiction novel, The Demolished Man, was originally serialised in Galaxy Science-Fiction magazine throughout January-March 1952. It told the story of Ben Reich, a ruthless business magnate who sought to commit murder in a society where telepathy made it impossible for people to conceal their criminal impulses. Displaying a cynical, “adult” sensibility rarely seen in science-fiction, The Demolished Man caused a minor sensation when it was published in book form in 1953. It won the inaugural Hugo Award for ‘Best Novel’ in 1953 and has since been recognized as the literary forerunner of the so-called “cyberpunk”science-fiction genre which flourished throughout the 1980s and 1990s.

The Stars My Destination

For his next novel, Bester turned to the French author Alexandre Dumas (1802-1870) for creative inspiration. ‘I’d been toying with the notion of using The Count of Monte Cristo as the pattern for a story’, as Bester later wrote in Hell’s Cartographers (Weidenfeld & Nicholson 1975). ‘The reason is simple – I’d always preferred the anti-hero and I’d always found high drama in compulsive types.’

‘[The story] remained a notion until I found a pile of old National Geographic magazines… [and] came across a piece about [a sailor] who lasted four months on an open raft. He’d been sighted several times by passing ships, which refused to change course to rescue him, because it was a Nazi submarine trick to put out decoys like this.’

This intriguing anecdote formed the kernel for Bester’s new work, which revolved around Gulliver (‘Gully’) Foyle, a brutish, primitive spaceman who is transformed into a ruthless instrument of revenge, after a passing spacecraft refuses to rescue him, leaving Gully Foyle to die in the airless confines of his own crippled rocket ship.

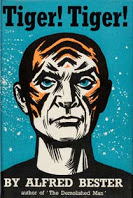

Bester’s second novel was first published in Britain under the title Tiger! Tiger! (Sidgwick & Jackson, 1956), inspired by William Blake’s famous poem, ‘The Tyger’(1794). However, when it was initially serialised in Galaxy Science Fictionlater that year, it was published under the alternate title, The Stars My Destination, at the suggestion of the magazine’s founding editor, H.L. Gold.

Bester’s second novel was first published in Britain under the title Tiger! Tiger! (Sidgwick & Jackson, 1956), inspired by William Blake’s famous poem, ‘The Tyger’(1794). However, when it was initially serialised in Galaxy Science Fictionlater that year, it was published under the alternate title, The Stars My Destination, at the suggestion of the magazine’s founding editor, H.L. Gold. The Brothers Pitt

The Stars My Destinationreceived mixed reviews from critics, but it was immediately recognised by Bester’s peers as a landmark work that set ambitious new standards for speculative fiction. Readers, too, embraced Bester’s novel – but even he could not have guessed how his latest work electrified the imagination of an avid science-fiction fan, living on the other side of the world.

Reg Pitt (1929-2010) was at that time a commercial illustrator and graphic designer, living in Sydney, Australia. He was also an avid science-fiction fan who, decades later, could still recall the thrill he felt when he first read Bester’s novel.

‘As soon as I read that first issue [of Galaxy], I was dying to read the rest of the book – and I became a lifelong fan of Alfred Bester, there and then.’

‘It made an indelible impression on me for so many years,’ he admits. ‘It became an obsession.’

Stan (L) and Reg Pitt (R), early 1950sReg was already immersed in science fiction, helping his elder brother Stanley Pitt (1925-2002) compile the comic-book version of the latter’s renowned newspaper strip, Silver Starr in the Flameworld.

Stan (L) and Reg Pitt (R), early 1950sReg was already immersed in science fiction, helping his elder brother Stanley Pitt (1925-2002) compile the comic-book version of the latter’s renowned newspaper strip, Silver Starr in the Flameworld.

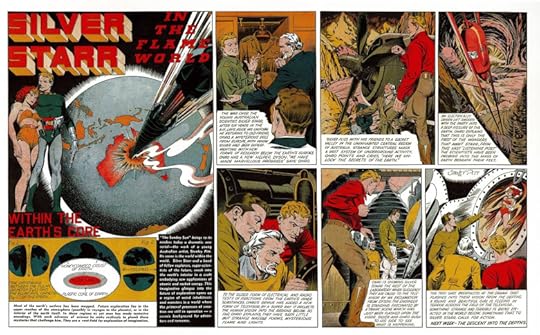

Silver Starr was an Australian soldier who served in the Pacific Theatre during World War Two. After he was discharged from the Army, he joined a daring expedition to the Earth’s core aboard a vessel capable of smashing through solid rock, built by the scientist Dr. Onro. Together, they discovered the mysterious Flame World and rescued its rightful ruler, Queen Pristine, from the evil despot, Tarka.

But the Silver Starr comic came about almost by accident, as Stan Pitt later recalled.

‘I did a [full-colour comic] called Nelson Power Conquers the Universe – it was never printed, incidentally, it never went on the market.’

Nelson Power Conquers the Universewas a revamped and extended version of “Universal Conquest”, a science-fiction serial written by Frank Ashley, who also wrote Stan’s first-ever comic book, Anthony Fury (Consolidated Press, 1942). Episodes of “Universal Conquest” appeared in various comics issued by Frank Johnson Publications (Sydney) during the mid-1940s.

‘But I introduced Silver Starr in the last panel and a friend of mine at the George Patterson advertising company in Sydney took [my artwork] along to Eric Kennedy, Chief Executive Officer of the Sunnewspaper, and he fell in love with the work.’

‘He asked me to come in and see him and he said, “This looks good, this one you’re talking about in this last panel, Silver Starr – I like the title ‘Silver Starr’”, he said. “Could you do Silver Starr for us?” and I said ‘Sure’.

Associated Newspapers, publishers of the Sunnewspaper, had lost publication rights to Flash Gordon(renamed “Speed Gordon” in Australia), and was understandably keen to secure a replacement for this popular American science-fiction serial for its weekend comics supplement.

They could not have found a better candidate than Stan Pitt, whose work – like so many comic artists of his generation – was greatly influenced by the peerless style of Alex Raymond (1909-1956), creator of Flash Gordon.

Silver Starr in the Flameworldmade its debut in Sydney’s Sunday Sun and Guardian newspaper on 24 November 1946. Initially spread over two tabloid pages and printed in sumptuous colour, Silver Starr was easily the most visually stunning Australian comic strip of the post-war era. Gradually, the strip was reduced to single page, then half-page instalments by the time its concluding episode appeared in November 1948 (See image below).

Reg Pitt contributed story ideas and dialogue, in addition to illustrating background scenes for Silver Starr in the Flameworld. He helped Stan reformat his original artwork for republication in the Silver Starr Super Comic, released by Young’s Merchandising Co. (Sydney) in 1950. The comic was reprinted in New Zealand by the Times Printing Works (Auckland), and briefly appeared in the British comic, Strange Worlds, in the early 1950s.

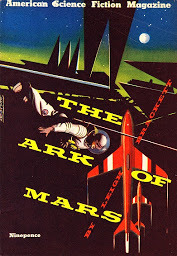

By now, Stan had become a sought-after commercial illustrator among advertising agencies and pulp/comic magazine publishers. During this period, Pitt painted a string of bold, eye-catching cover illustrations for

American Science Fiction

, which reprinted short stories by such prominent American authors as Leigh Brackett, Robert Heinlein, and John W. Campbell. American Science Fiction Magazine, like many Australian “pulp fiction” titles of its day, was a 36-page “novelette” digest by Malian Press (Sydney), and ran for 41 issues throughout 1952-55. Stan’s cover illustrations were greatly enhanced by Reg’s imaginative layouts and sophisticated logo designs, making these covers classic examples of 1950s-era science-fiction illustration.

By now, Stan had become a sought-after commercial illustrator among advertising agencies and pulp/comic magazine publishers. During this period, Pitt painted a string of bold, eye-catching cover illustrations for

American Science Fiction

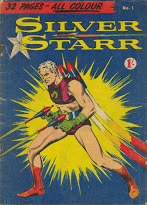

, which reprinted short stories by such prominent American authors as Leigh Brackett, Robert Heinlein, and John W. Campbell. American Science Fiction Magazine, like many Australian “pulp fiction” titles of its day, was a 36-page “novelette” digest by Malian Press (Sydney), and ran for 41 issues throughout 1952-55. Stan’s cover illustrations were greatly enhanced by Reg’s imaginative layouts and sophisticated logo designs, making these covers classic examples of 1950s-era science-fiction illustration.  Stan had by this time begun working for the Cleveland Publishing Company (Sydney), which was fast becoming a dominant force in Australia’s “pulp fiction” magazine market, thanks in part to its wildly successful Larry Kent/I Hate Crime series. The company’s founder, Jack Atkins, was determined to capture a share of the local comic book market, and commissioned Stan to produce an all-new Silver Starr comic, published in full colour. Sadly, this proved to be a costly failure, with most of the comic’s 100,000-copy print run eventually being sold through supermarket chains at heavily discounted prices. Silver Starrwas released in 1956, just as newly launched television broadcasting services were having a calamitous effect in the local comics industry. The new, full-colour series of Silver Starr did not survive beyond its debut issue, but Reg and Stan Pitt repackaged earlier “Silver Starr” stories for Cleveland Publishing’s King Size Comic, for which they also produced new instalments of their evergreen science-fiction hero.

Stan had by this time begun working for the Cleveland Publishing Company (Sydney), which was fast becoming a dominant force in Australia’s “pulp fiction” magazine market, thanks in part to its wildly successful Larry Kent/I Hate Crime series. The company’s founder, Jack Atkins, was determined to capture a share of the local comic book market, and commissioned Stan to produce an all-new Silver Starr comic, published in full colour. Sadly, this proved to be a costly failure, with most of the comic’s 100,000-copy print run eventually being sold through supermarket chains at heavily discounted prices. Silver Starrwas released in 1956, just as newly launched television broadcasting services were having a calamitous effect in the local comics industry. The new, full-colour series of Silver Starr did not survive beyond its debut issue, but Reg and Stan Pitt repackaged earlier “Silver Starr” stories for Cleveland Publishing’s King Size Comic, for which they also produced new instalments of their evergreen science-fiction hero.

End of Part 1

The author would like to thank the following people, whose gracious assistance and generosity of time made this article possible: Graeme Cliffe; Dr. Jasmine Henderson; Luke Pitt; Reg Pitt; Dennis Ray; and John Weeks. All errors and omissions, however, are the author’s own.

Text © copyright 2007-2020 Kevin Patrick and cannot be reproduced without the author’s permission, except for purposes of comment and review. All featured artwork and/or images are © copyright 2007-2020 their respective copyright holders and are reproduced here for the purpose of comment and criticism.

All quotes attributed to Stanley Pitt are taken from a transcript of a radio interview (© Spectrum FM Radio) conducted by John Weeks on 1 November 1997 on 3MDR 97.1 FM, Victoria, Australia, and used with permission.