A Breakdown of HTTP Clients in Elixir

Elixir's ecosystem has quite a few HTTP clients at this point. But what'sthe best one? In this post, I want to break down a bunch of the clients wehave available. I'll give an overview of the clients I personally like the most,and I'll talk about which clients are the best choice in different use cases.I'll also share some advice with library authors.

This is AI generated, just to be clear

All Your Clients Are Belong to UsSo, let's take a whirlwind tour of some HTTP clients available in Elixir. We'lltalk about these:

MintFinchReqhttpcThis is not a comprehensive list of all the Elixir HTTP clients, but rather alist of clients that I think make sense in different situation. At the end ofthis post, you'll also find a mention of other well-known clients, as well asadvice for library authors.

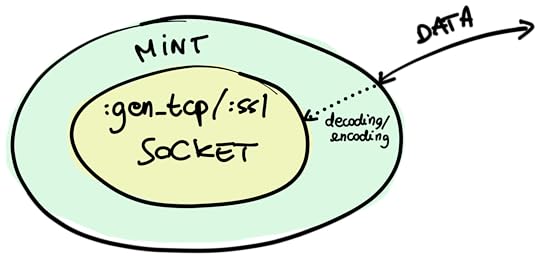

MintLet's start with Mint. Mint is arguably the lowest-level HTTP clientwe've got in Elixir. It's essentially a wrapper around a raw TCP or SSLsocket. Its job is to make the socket aware of the network protocol. It'sstateless, meaning that all you deal with is a "connection" data structure, andit's process-less, meaning that it doesn't impose any process architecture onyou.

Think about a :gen_tcp or a :ssl socket. Their job is to allow you toconnect servers and clients on the TCP and TLS network protocols, respectively.When you're using one of these directly, you usually have to do most of theencoding of decoding of the data that you're sending or receiving, because thesockets carry just binary data.

Mint introduces an abstraction layer around raw sockets, rather than on topof them. Here's a visual representation:

When you use Mint, you have an API that is similar to the one provided by the:gen_tcp and :ssl modules, and you're using a socket underneath. Mintprovides a data structure that it calls a connection, which wraps theunderlying socket. A Mint connection is aware of the HTTP protocol, so you don'tsend and receive raw binary data here, but rather data that makes sense in thesemantics of HTTP.

For example, let's see how you'd make a request using Mint. First, you'd want toopen a connection. Mint itself is stateless, and it stores all theconnection information inside the connection data structure itself.

{:ok, conn} = Mint.HTTP.connect(:http, "httpbin.org", 80)Then, you'd use Mint.HTTP.request/5 to send arequest.

{:ok, conn, request_ref} = Mint.HTTP.request(conn, "GET", "/", [], "")Sending a request is analogous to sending raw binary data on a :gen_tcp or:ssl socket: it's not blocking. The call to request/5 returns right away,giving you a request reference back. The underlying socket will eventuallyreceive a response as an Erlang message. At that point, you can useMint.HTTP.stream/2 to turn that message into something that makes sense inHTTP.

receive do message -> {:ok, conn, responses} = Mint.HTTP.stream(conn, message) IO.inspect(responses)end#=> [#=> {:status, #Reference<...>, 200},#=> {:headers, #Reference<...>, [{"connection", "keep-alive"}, ...},#=> {:data, #Reference<...>, "<!DOCTYPE html>..."},#=> {:done, #Reference<...>}#=> ]Mint supports HTTP/1.1 and HTTP/2 out of the box, as well as WebSocket throughmint_web_socket.

When to Use MintGenerally, don't use Mint. Seriously. You know I mean this advice, becauseI'm one of the two people who maintain andoriginally created Mint itself! For most use cases, Mint is too lowlevel. When you use it, you'll have to care about things such as poolingconnections, process architecture, keeping the connection structs around, and soon. It's a bit like what you'd do in other cases, after all. For example, you'reunlikely to use :gen_tcp to communicate directly with your PostgreSQLdatabase. Instead, you'd probably reach at least for something likePostgrex to abstract a lot of the complexity away.

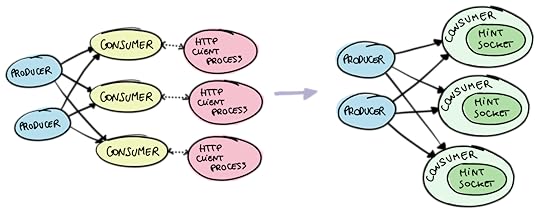

Still, there are some use cases where Mint can make a lot of sense. First andforemost, you can use it to build higher-level abstractions. That's exactly whata library called Finch does, which we'll talk about in a bit. Mint can also beuseful in cases where you need fine-grained control over the performance andprocess architecture of your application. For example, say you have a fine-tunedGenStage pipeline where you need to make some HTTP calls at somepoint. GenStage stages are already processes, so having an HTTP client based ona process might introduce an unnecessary layer of processes in your application.Mint being processless solves exactly that.

A few years ago, I worked at a company where we would've likely used Mint inexactly this way. At the time, I wrote a blogpost that goes into more detail in case you'reinterested.

Bonus: Why Isn't Mint in the Elixir Standard Library?That's a great question! When we introduced Mint back in 2019, we posted aboutit on Elixir's website. Our original intention was to ship Mintwith Elixir's standard library. This is also one of the reasons why we wroteMint in Elixir, instead of Erlang. However, we then realized that it worked wellas a standalone library, and including it into the standard library wouldincrease the cost of maintaining the language as well as potentially slow downthe development of Mint itself.

That said, I think of Mint as the "standard-library HTTP client", that is, thelow-level client that you'd expect in the standard library of a language likeElixir.

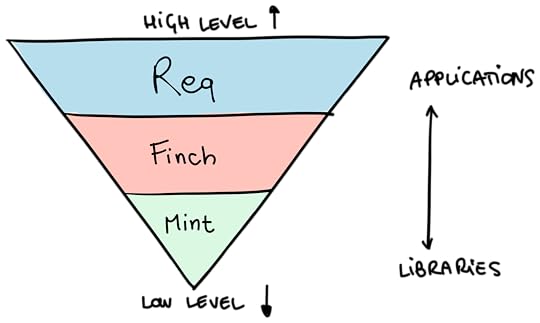

FinchFinch is a client built on top of Mint. It serves an important job inthe "pyramid of abstractions" of HTTP clients listed in this post: pooling.Finch provides pooling for Mint connections. Using Mint on its own meansimplementing some sort of strategy to store and pool connections, which is whatFinch provides.

Finch is quite smart about its pooling. It uses nimble_pool when poolingHTTP/1.1 connections. The nimble_pool library is a tiny resource-poolimplementation heavily focused on a small resource-usage footprint as well as onperformance. Since HTTP/2 works quite differently from HTTP/1.1 and the formeris capable of multiplexing requests, Finch uses a completely different strategyfor HTTP/2, without any pooling. All of this is transparent to users.

The API that Finch provides is still quite low-level, with manual requestbuilding and such:

{:ok, _} = Finch.start_link(name: MyFinch)Finch.build(:get, "https://hex.pm") |> Finch.request(MyFinch)#=> {:ok, %Finch.Response{...}}However, but the convenience of pooling and reconnections that Finch provides isfantastic.

Okay, when to use Finch then? Personally, I think Finch is a fantastic librarywhenever you have performance-sensitive applications where you're ready tosacrifice some of the convenience provided by "higher-level" clients. It's alsogreat when you know you'll have to make a lot of requests to the same host,since you can specify dedicated connection pools per host. This is especiallyuseful when communicating across internal services, or talking to third-partyAPIs.

ReqReq is a relatively-new kid on the block when it comes to HTTP clients inElixir. It's one of my favorite Elixir libraries out there.

Req.get!("https://api.github.com/repos/wojtekma... "Req is a batteries-included HTTP client for Elixir."It's built on top of Finch, and it takes a quite "functional-programming"approach to HTTP. What I mean by that is that Req revolves around aReq.Request data structure, which you manipulate to addoptions, callbacks, headers, and more before making an HTTP request.

req = Req.Request.new(method: :get, url: "https://github.com/...") |> Req.Request.append_request_steps( put_user_agent: &Req.Steps.put_user_agent/1 ) |> Req.Request.append_response_steps( decompress_body: &Req.Steps.decompress_body/1, decode_body: &Req.Steps.decode_body/1 ) |> Req.Request.append_error_steps(retry: &Req.Steps.retry/1){req, resp} = Req.Request.run_request(req)Req is extensively customizable, since you can writeplugins for it in order to build HTTP clients thatare tailored to your application.

When To Use ReqFirst and foremost, Req is fantastic for scripting. With the introduction ofMix.install/2 in Elixir 1.12, using libraries in Elixirscripts is a breeze, and Req fits like a glove.

Mix.install([ {:req, "~> 0.3.0"}])Req.get!("https://andrealeopardi.com").hea... [#=> {"connection", "keep-alive"},#=> ...#=> ]Req is also a great fit to use in your applications. It provides a ton offeatures and plugins to use for things like encoding and decoding requestbodies, instrumentation, authentication, and so much more. I'll take a quotestraight from Finch's README here:

Most developers will most likely prefer to use the fabulous HTTP clientReq which takes advantage of Finch's pooling and provides an extremelyfriendly and pleasant to use API.

So, yeah. In your applications, unless you have some of the needs that wedescribed so far, just go with Req.

httpcWhile Mint is the lowest-level HTTP client I know of, there's another clientworth mentioning alongside it: httpc. httpc ships with the Erlangstandard library, making it the only HTTP client in the ecosystem thatdoesn't require any additional dependencies. This is so appealing! There arecases where not having dependencies is a huge bonus. For example, if you're alibrary author, being able to make HTTP requests without having to bring inadditional dependencies can be great, because those additional dependencieswould trickle down (as transitive dependencies) to all users of your library.

However, httpc has major drawbacks. One of them is that it provides littlecontrol over connection pooling. This is usually fine in cases where you need afew one-off HTTP requests or where your throughput needs are low, but it can beproblematic if you need to make a lot of HTTP requests. Another drawback is thatits API is, how to put it, awkward.

{:ok, {{version, 200, reason_phrase}, headers, body}} = :httpc.request(:get, {~c"http://www.erlang.org", []}, [], [])The API is quite low level in some aspects, since it can make it hard to composefunctionality and requires you to write custom code for common functionalitysuch as authentication, compression, instrumentation, and so on.

That said, the main drawback of httpc in my opinion is security. While allHTTP clients on the BEAM use ssl sockets under the hood (whenusing TLS), some are much better at providing secure defaults.

iex> :httpc.request(:get, {~c"https://wrong.host.badssl.com", []}, [], [])09:01:35.967 [warning] Description: ~c"Server authenticity is not verified since certificate path validation is not enabled" Reason: ~c"The option {verify, verify_peer} and one of the options 'cacertfile' or 'cacerts' are required to enable this."While you do get a warning regarding the bad SSL certificate here, the requeststill goes through. The good news is that this is mostly going away from OTP 26onward, since OTP 26 made SSL defaults significantlysafer.

When to Use httpcSo, when to use httpc? I would personally recommend httpc only when the mostimportant goal is to not have any external dependencies. The perfect example forthis is Elixir's package manager itself, Hex. Hex useshttpc because, if you think about it, what would be thealternative? You need Hex to fetch dependencies in your Elixir projects, so itwould be a nasty chicken-and-egg problem to try to use a third-party HTTP clientto fetch libraries over HTTP (including that client!).

Other libraries that use httpc are Tailwind andEsbuild. Both of these use httpc to download artifacts the firsttime they run, so using a more complex HTTP client (at the cost of additionaldependencies) isn't really necessary.

Choosing the Right ClientI've tried to write a bit about when to use each client so far, but to recap,these are my loose recommendations:

ClientWhenMintYou need 100% control on connections and request lifecycleMintYou already have a process architecture, and don't want to introduce any more processesMintYou're a library author, and you want to force as few dependencies as possible on your users while being mindful of performance and security (so no httpc)FinchYou need a low-level client with high performance, transparent support for HTTP/1.1 (with pooling) and HTTP/2 (with multiplexing)ReqMost applications that make HTTP callsReqScriptinghttpcYou're a (hardcore) library author who needs a few HTTP requests in their library, but you don't want to add unnecessary transitive dependencies for your usersSome of the HTTP clients I've talked about here form sort of an abstractionpyramid.

I want to also talk about library authors here. If you're the author of alibrary that needs to make HTTP calls, you have the options we talked about. Ifyou're only making a handful of one-off HTTP calls, then I'd go with httpc, sothat you don't have any impact on downstream code that depends on your library.However, if making HTTP requests is central to your library, I would reallyrecommend you use the "adapter behaviour" technique.

What I mean by adapter behaviour technique is that ideally you'd build aninterface for what you need your HTTP client to do in your library. For example,if you're building a client for an error-reporting service (such asSentry), you might only care about making synchronous POST requests.In those cases, you can define a behaviour in your library:

defmodule SentryClient.HTTPClientBehaviour do @type status() :: 100..599 @type headers() :: [{String.t(), String.t()}] @type body() :: binary() @callback post(url :: String.t(), headers(), body()) :: {:ok, status(), headers(), body()} | {:error, term()}endThis would be a public interface, allowing your users to implement their ownclients. This allows users to choose a client that they're already using intheir codebase, for example. You can still provide a default implementation thatships with your library and uses the client of your choice. Incidentally, thisis exactly what the Sentry library for Elixir does: it ships with a defaultclient based on Hackney. If you go with thisapproach, remember to make the HTTP client an optional dependency of yourlibrary:

# In mix.exsdefp deps do [ # ..., {:hackney, "~> 1.0", optional: true} ]endWhat About the Others?These are not all the HTTP clients available in Elixir, let alone on the BEAM! Ihave not mentioned well-known Elixir clients such as HTTPoison andTesla, nor Erlang clients such as hackney.

HTTPoisonHTTPoison is an Elixir wrapper on top of hackney:

HTTPoison.get!("https://example.com")#=> %HTTPoison.Response{...}Because of this, I tend to not really use HTTPoison and, if necessary, gostraight to hackney.

Hackneyhackney is a widely-used Erlang client which provides a nice and modern API andhas support for streaming requests, compression, encoding, file uploads, andmore. If your project is an Erlang project (which is not the focus of thispost), hackney can be a good choice.

:hackney.request(:get, "https://example.com", [])#=> {:ok, 200, [...], "..."}However, hackney presents some issues in my opinion. The first is that hackneyhad questionable security defaults. It uses good defaults, but when changingeven a single SSL option, then it drops all those defaults. This is prone tosecurity flaws, because users don't always fill in secure options. While nottechnically a fault of the library itself, the API makes it easy to mess up:

# Secure defaults::hackney.get("https://wrong.host.badssl.com")#... {:error, {:tls_alert, {:handshake_failure, ...# When changing any SSL options, no secure defaults anymore:ssl_options = [reuse_sessions: true]:hackney.get("https://wrong.host.badssl.com", [], "", ssl_options: ssl_options)# 11:52:32.033 [warning] Description: ~c"Server authenticity is not verified ...#=> {:ok, 200, ...}In the second example above, where I changed the reuse_sessions SSL options,you get a warning about the host's authenticity, but the request goes through.

Another thing that I think could be improved in hackney is that it brings in awhopping seven dependencies. They're all pertinent to what hackney does, butit's quite a few in my opinion.

Last but not least, hackney doesn't use the standard telemetry library toreport metrics, which can make it a bit of a hassle to wire in metrics (sincemany Elixir applications, at this point, use telemetry for instrumentation).

One important thing to mention: while HTTPoison is a wrapper around hackney, itsversion 2.0.0 fixes the potentially-unsecure SSL behaviorthat we just described for hackney.

TeslaTesla is a pretty widely-used HTTP client for Elixir. It provides asimilar level of abstraction as Req. In my opinion, its main advantage is thatit provides swappable HTTP client adapters, meaning that you can use itscommon API but choose the underlying HTTP client among ones like Mint, hackney,and more. Luckily, this feature is in the works for Req as well.

The reason I tend to not reach for Tesla is mostly that, in my opinion, itrelies a bit too much on module-based configuration and meta-programming. Incomparison, I find Req's functional API easier to compose, abstract, and reuse.

There are other clients in Erlang and Elixir: gun, ibrowse, andmore. But we gotta draw a line at some point!

ConclusionsWe went through a bunch of stuff here. We talked about the clients I personallylike and recommend for different use cases. You also got a nice little summarytable for when to use each of those client. Last but not least, I mentioned someother clients as well reasons why I prefer the ones in this post.

That's all. Happy HTTP'ing!

AcknowledgementsI want to thank a few folks for helping review this post before it went out. Thank you Jos��, Wojtek, and Jean.