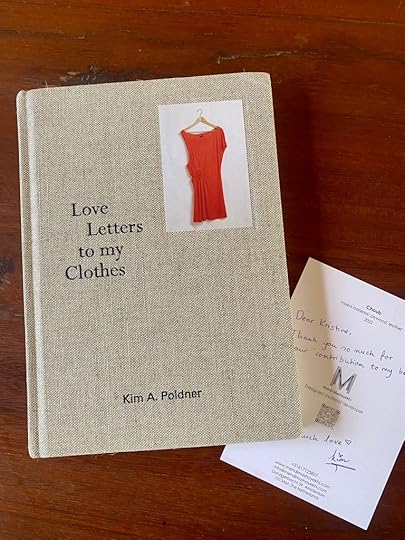

Introduction to the book ‘Love Letters to my Clothes’

I recently had the pleasure of writing the foreword to Kim A. Poldner’s new book Love letters to my clothes. It is an inspiring and extremely aesthetically nourishing book that celebrates the clothes we wear and love — and by doing so, investigates the difference between meaningful and meaningless garments.

Kim has given me permission to share the foreword here with you, and I will follow up with an interview with Kim next month.

This book is a celebration of user traces and decay, of loving bonds between people and their belongings, of the time that lingers and adds character to lovingly used things, and of inclusive sustainability. The garments in this book are carriers of time and an embodied discussion on how decay can keep an initial object-crush fresh and broaden our perspective on what sustainable fashion encompasses. They constitute a material manifesto of long-term usage.

In my books on aesthetic sustainability and design I have explored what object related sustainability means and what a justifiable life worth sustaining involves. Repetitions and endurance are crucial elements. But sustainable living also involves letting go of actions, relationships, and objects that are not — or are no longer — beneficial, constructive, or worth sustaining in relation to one’s life’s journey. In Love Letters to my Clothes this is exactly what Kim A. Poldner does.

Prolonging the lifespan of our belongings constitutes a cornerstone in sustainable living: being mindful of what we buy and focusing on the usage and the value of things rather than on the momentary newness fix. Long-term usage involves mending, improving, and caring. But, as the only constant is change — like a wise man said thousands of years ago (Heraclitus, Pre-Socratic Greek philosopher, 544 BCE) — sometimes it is time to let go. When things no longer fulfil or serve us but start to drain us or keep us stuck in the past, or when things are so closed that their aesthetics are no longer nourishing, it might be time to say goodbye — with love and gratitude for the time they served us, of course.

However, just imagine if some of the potentially resilient clothes in the book — like the Karen Millen dress (that was somehow always too static for the author to fall deeply in love with) or the Silk dress (that literally fell apart) — had been designed to be open to wear and tear, open to usage, and open to life. They could have then stayed in the author’s wardrobe for years and years to come; developed with her changing needs or altering body. Instead of being discarded, they could have been an ever-evolving aesthetic display of usage and life. When things are closed, however, they have an expiration date.

Sustainable fashion should be open rather than closed.

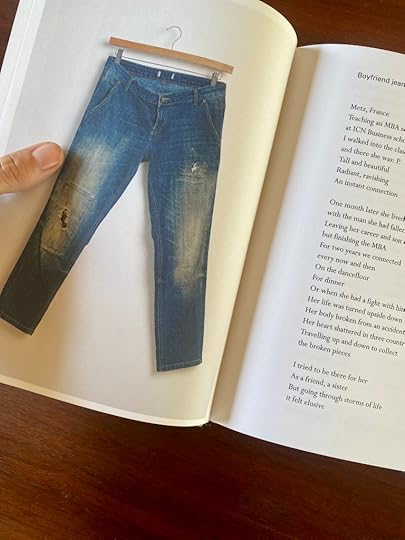

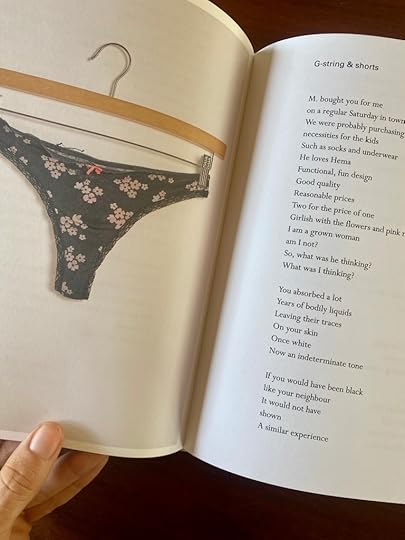

Images from the book Love Letters to my Clothes

Images from the book Love Letters to my Clothes

Besides the celebration of decay, the book presents an intriguing, and much needed, democratic, non-elitist approach to sustainability. By exhibiting her decaying pieces of clothing, and even serenading them, the author challenges what it means to be well-dressed. This display contains an inherent critique of materialistic, flashy status symbols as well as a refreshing appeal for new (sustainable) forms of cultural, societal prestige. Maybe the new well-dressed could be wearing mended garments and uniquely combined preloved outfits; flashing creativity and sense of aesthetics rather than purchasing power?

At present, however, it appears that sustainability has become the new luxury — and not in the “wear-your-clothes-till-they-fall-apart” kind of way. Despite repairing and reusing being both affordable and approachable ways of life, they (still) don’t seem to be vastly common. And furthermore, the least well-off seem to be the least engaged in such sustainable (and affordable) activities.

Why? Well, in order to be able to repair one’s belongings, they must be repairable, and in order to reuse things, they must decay in an aesthetically pleasing way. And generally cheap mass-produced things do not. They are produced to be obsolete after a short period of usage. Sustainable design-objects created for longevity on the other hand are typically marketed as luxurious, which seems to legitimise their price tag. Of course, slowly crafted, thoroughly designed objects and well-researched sustainable design solutions are pricier than mass-produced goods (and rightfully so). But creating affordable enduring, repairable things is not impossible.

When sustainable design is branded as yet another traditional status-symbol, or yet another way to express wealth, living sustainably alters from being the most reasonable way of life to being out of reach for the vast majority. Sustainable living should be interlinked with simplicity and community, repairing and sharing, but instead it primarily connotes good (expensive) materials, silent retreats, slowness, and electric vehicles. Sustainability has become for the fortunate well-off and well-informed few; it profits from righteousness and class-divisions. There is no community-feeling in exclusive sustainability.

Some of the clothes I would write love letters to.

Some of the clothes I would write love letters to.

I have lived in Bali, Indonesia for four years. And sustainability here is an entirely different conversation than when I was living in Denmark (which highlights the point on class-division). Let me explain.

When I just moved here, I spoke at a sustainable design festival. My focus was on aesthetic sustainability, the importance of investing in durable things, and how decay can beautify a well-made piece of furniture or clothing. There was a question from the crowd: “What if you cannot afford to invest in slowly crafted garments that age with beauty?” It was a relevant question. Because despite the fact that investing in durable things that can continuously nourish us aesthetically is probably the most affordable in the long run, this is not an option for everyone. If you have no savings, then how can you invest?

However, despite investing in thoroughly crafted, well-designed garments not being an option for everyone, there is one thing we can all do. And that is buying (mainly) second-hand. So why don’t we? I think the only answer to that question is that there is (still) a stigma connected with discarded things. Especially when it comes to clothes. And here in Indonesia this stigma is substantial. There is a visible amount of prestige interlinked with purchasing and flashing a glittery new plastic wrapped accessory or a chalky white synthetic statement t-shirt, never used before, and cheap enough to discard after a few times of wear; even in a place like this where the average salary is around 20 euros a day.

In my birth country Denmark too, there is still a degree of hesitation to track in relation to second-hand clothes. Buying new (sustainable) clothes remains more prestigious than buying used. And this despite the immense societal focus on recycling.

So, what is the solution? I think there are two solutions, actually, and that they need to go hand in hand. The first one being making it cool to wear preloved clothes by eliminating the cultural stigma, and the second one being democratising sustainability. Easier said than done, obviously.

In order to make second-hand garments cool we need more embodied manifestos of usage, like Love Letters to My Clothes. We need to preserve the intimate love-relation to our favourite clothes, focus on the aesthetically nourishing qualities of preloved garments, and celebrate the stories and memories that are stored in our wardrobe. And of course, we need to highlight the coolness-factor interlinked with unique outfits, creative mends, and beautifying wear and tear.

The art of democratising sustainability doesn’t only involve simplifying sustainable solutions in order to make them more affordable. It also requires a change in habitual mass-consumption. This change could be fueled by an understanding that unless the vast majority of people find pride in living sustainably the real healing will never happen.

Sustainable living should be inclusive rather than exclusive.