On This Day in February 1807 (and the next) – The Battle of Eylau

(This day being February 6th, and the next being February 7th, of course)

Napoleon had arrived in Warsaw in the days leading up to Christmas 1806. He soon discovered the joys of his Polish mistress, The Countess Maria Walewska, who reluctantly gave into her countryman’s demands to ease the Emperor’s solitude and loneliness, in hope of having their country’s sovereignty restored. She found in finally capitulating to do so, that she indeed would come to deeply ove the man beneath the famous bicorne hat. Unlike so many others, Marie Walewska stayed faithful to him until his death, and then to her own thereafter.

But this day’s story begins with the hunger and restlessness not of Napoleon, but of his Marshal Michel Ney. Ney was perhaps the most impetuous of the Napoleonic Marshals. While many were bivouacked around Warsaw for the Winter of 1806/1807 in assigned locations, Ney’s VI Corps soon had expended the lands assigned to them for the foraging of foods. So, against the Emperor’s explicit orders, Ney headed north in search of forage. Soon he found himself crossing the border into Eastern Prussia, a state Napoleon was still at war with along with their Russian allies. Near the town of Allenstein (today’s Olsztyn, Poland), Ney stumbled across a stealthy Winter attack force led by the Russian General Levin August von Bennigsen. Hey was tremendously outnumbered, but relayed the location and direction of the Russians to Napoleon, then still in Warsaw.

Levin August Bennigsen

Levin August BennigsenNapoleon decided to temptingly dangle a small force of troops on his left flank near the Polish town of Torun, then named Thorny the vacating Prussians. The Emperor intended to lure Bennigsen’s army toward Torun and then drive his own forces northward, encircling the Russians from behind. But his plan was spoiled when his orders were given by a freshly arrived junior officer to carry to the troops/ unfamiliar with the lay of the land, the messenger got lost, and quickly captured by Russian Cossacks. Bennigsen was made aware of the trap and retreated north toward East Prussia. Eventually after some skirmishing, on February 6, 1807, Napoleon’s forces engaged Bennigsen at the Prussian village of Ella. Over that afternoon/night and throughout the following day the French and Russians (with some Prussian help) fought through Winter snows bordering on blizzard conditions. The battle was too eventful to fully cover here, but the soldiers fought door-to-door in the village, hand-to-hand in its cemetery, and cannon shot for cannon shot across its frozen snowy plains, Napoleon was nearly captured but for the heroics of his Old Guard (the Grumblers, as they were called. One French unit sent to attack the Russian lines during the heaviest snows became disoriented in the whiteout and soon found themselves in no man’s land between the two sides of artillery and were obliterated. Then Marshal Murat, Napoleon’s brother-in-law led one of the greatest calvary charges in European history to save those who still miraculously survived. While the regiment of Polish lancers would not be formally comished until a few months later, Many, many Poles fought and died in this conflict.

Attack of the cemetery, painted by Jean-Antoine-Siméon Fort

Attack of the cemetery, painted by Jean-Antoine-Siméon FortAll in all, it was one of the bloodiest engagements of the Napoleonic Wars. After the second day, the Russians pulled their forces back even deeper into East Prussia, leavingg Napoleon to claim victory. But all knew in truth it was a draw. For the first time, Napoleon proved not to be invincible/ The Myth was, if not destroyed, heavily tarnished.

Napoleon would in the months following the Battle of Eylau defeat Tsar Alexander’s forces and declare Peace at Tilsit in June 1807. France and Russia became allies (for a bit), but when Napoleon took Moscow in 1812, Alexander recalled Eylau, and how the French “Monster” had been battled to a draw.

And back to Marshal Ney, who after the battle reviewed all the dead strew so far and wide, said famously,

In January 1807, the new Russian army commander, Levin August von Bennigsen, attempted to surprise the French left wing by shifting the bulk of his army north from Nowogród to East Prussia. Incorporating a Prussian corps on his right, he first bumped into elements of the VI Corps of Marshal Michel Ney, who had disobeyed his emperor’s orders and advanced far north of his assigned winter cantonments. Having cleared Ney’s troops out of the way, the Russians rolled down on the isolated French I Corps under Marshal Jean-Baptiste Bernadotte. Tough fighting at the Battle of Mohrungen allowed Bernadotte’s corps to escape serious damage and pull back to the southwest. With his customary inventiveness, Napoleon saw an opportunity to turn the situation to his own advantage. He instructed Bernadotte to withdraw before Bennigsen’s forces and ordered the balance of the Grande Armée to strike northward. That maneuver might envelop the Russian army’s left flank and cut off its retreat to the east. By a stroke of luck, a band of Cossacks captured a messenger carrying Napoleon’s plans to Bernadotte and quickly forwarded the information to General Pyotr Bagration. Bernadotte was left unaware, and a forewarned Bennigsen immediately ordered a retreat east to Jonkowo to avoid the trap.

As Bennigsen hurriedly assembled his army at Jonkowo, elements of Marshal Nicolas Soult‘s IV Corpsreached a position on his left rear on 3 February.[16] That day, General of Division Jean François Leval clashed with Lieutenant-General Nikolay Kamensky‘s 14th Division at Bergfried (Berkweda) on the Alle (Łyna) River, which flows roughly northward in the area. The French reported 306 casualties but claimed to have inflicted 1,100 on their adversaries.[17] After seizing Allenstein (Olsztyn), Soult moved north on the east bank of the Alle. Meanwhile, Napoleon threatened Bennigsen from the south with Marshal Pierre Augereau‘s VII Corps and Ney’s forces. Kamensky held the west bank with four Russian battalions and three Prussian artillery batteries.[16] After an initial attack on Bergfried had been driven back, the French captured the village and bridge. A Russian counterattack briefly recaptured the bridge. That night, the French remained in possession of the field, and Soult claimed that he had found 800 Russian dead there.[18] Marching at night, Bennigsen retreated directly north to Wolfsdorf (Wilczowo) on the 4th. The next day, he fell back to the northeast, reaching Burgerswalde on the road to Landsberg (Górowo Iławeckie).[19]

By early February, the Russian army was in full retreat and was relentlessly pursued by the French. After several aborted attempts to stand and fight, Bennigsen resolved to retreat to the town of Preussisch-Eylau and there make a stand. During the pursuit, perhaps influenced by the dreadful state of the Polish roads, the savage winter weather and the relative ease with which his forces had dealt with Prussia, Napoleon had allowed the Grande Armée to become more spread out than was his custom. In contrast, Bennigsen’s forces were already concentrated.

BattleFirst daySee also: Eylau order of battle

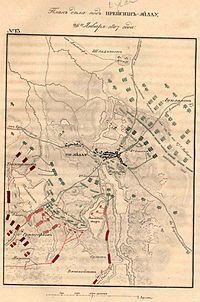

Battle of Eylau in the early stages. French shown in red, Russians in green and Prussians in blue.

Battle of Eylau in the early stages. French shown in red, Russians in green and Prussians in blue.Marshal Soult‘s IV Corps and Marshal Murat‘s cavalry were the first French formations to reach the plateau before Eylau at about 14:00 on the 7th. The Russian rearguard under Bagration occupied positions on the plateau about a mile in front of Eylau. The French promptly assaulted the positions and were repulsed. Bagration’s orders were to offer stiff resistance to gain time for Bennigsen’s heavy artillery to pass through Eylau and to join the Russian army in its position beyond Eylau. During the afternoon, the French were reinforced by Marshal Augereau‘s corps and the Imperial Guard, giving him a force of about 45,000 soldiers in all. Under pressure of greatly superior forces, Bagration conducted an orderly retreat to join the main army. It was covered by another rearguard detachment in Eylau that was led by Barclay de Tolly.

The rearguard action continued when French forces advanced to assault Barclay’s forces in the town of Eylau. Historians differ on the reasons. Napoleon later claimed that was on his orders and that the advance had the dual aims of pinning the Russian force to prevent it from retreating yet again and of providing his soldiers with at least some shelter against the terrible cold. Other surviving evidence, however, strongly suggests that the advance was unplanned and occurred as the result of an undisciplined skirmish, which Marshals Soult and Murat should have acted to quell but failed to do so. Whether or not Napoleon and his generals had considered securing the town to provide the soldiers with shelter for the freezing night, the soldiers may have taken action on their own initiative to secure such a shelter. According to Captain Marbot, the Emperor had told Marshal Augereau that he disliked night fighting, that he wanted to wait until the morning so that he could count on Davout’s Corps to come up on the right wing and Ney’s on the left and that the high ground before Eylau was a good easily defensible position on which to wait for reinforcements.

Whatever the cause of the fight for the town, it rapidly escalated into a large and bitterly fought engagement, continuing well after night had fallen and resulting in about 4,000 casualties to each side, including Barclay, who was shot in the arm and forced to leave the battlefield. Among other officers, French Brig. Gen. Pierre-Charles Lochet was shot and killed. At 22:00 Bennigsen ordered the Russians to retreat a short distance, leaving the town to the French. He later claimed he abandoned the town to lure the French into attacking his center the next day. Despite their possession of the town, most of the French spent the night in the open, as did all of the Russians. Both sides did without food—the Russians because of their habitual disorganization, the French because of problems with the roads, the weather and the crush of troops hurrying towards the battle.

During the night, Bennigsen withdrew some of his troops from the front line to strengthen his reserve. That resulted in the shortening of his right wing.

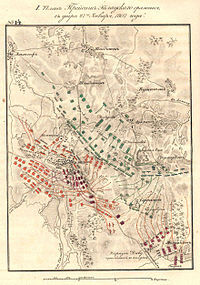

Second day Battle of Eylau early on the second day. French shown in red, Russians in green, Prussians in blue.

Battle of Eylau early on the second day. French shown in red, Russians in green, Prussians in blue.Alternative detailed Maps

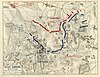

Situation early 8 February 1807

Situation about 1600, 8 February 1807

(by West Point Military Academy)

Bennigsen had 67,000 Russian troops and 400 guns already assembled, but the French had only 49,000 troops and 300 guns. The Russians could expect to be reinforced by Von L’Estocq‘s detachment of 9,000 Prussians, the French by Marshal Davout‘s depleted III Corps (proud victors of Auerstedt but now only 15,000 strong) and Marshal Ney‘s 14,000-strong VI Corps (for a total of 74,000 men), which was shadowing the Prussians. Bernadotte’s I Corps was too far distant to take part.

Dawn brought light but little warmth and no great improvement in visibility since the heavy snowstorms continued throughout the day. The opposing forces occupied two parallel ridges. The French were active early on probing the Russian position, particularly on the Russian right. Bennigsen, fearing that the French would discover that he had shortened his right, opened the battle by ordering his artillery to fire on the French. They replied and the ensuing artillery duel lasted for some time, with the French having the best of it because of their more dispersed locations.

The start of the artillery duel galvanised Napoleon. Until then, he had expected the Russians to continue their retreat, but he now knew that he had a fight on his hands. Messengers hurriedly were dispatched to Ney to order him to march on Eylau and to join the French left wing.

Meanwhile, the French had occupied in force some fulling mill buildings within musket range of the Russian right wing. Russian jagers ejected them. Both sides escalated the fight, with the Russians assaulting the French left on Windmill Knoll to the left of Eylau. Napoleon interpreted the Russian efforts on his left as a prelude to an attack on Eylau from that quarter. By then, Davout’s III Corps had begun to arrive on the Russian left.

To forestall the perceived Russian attack on Eylau and to pin the Russian army so that Davout’s flank attack would be more successful, Napoleon launched an attack against the Russian centre and left, with Augereau’s VII Corps on the left and Saint-Hilaire‘s Division of Soult’s IV Corps on the right.

Portrait of Joachim Murat by Antoine-Jean Gros

Portrait of Joachim Murat by Antoine-Jean GrosAugereau was very ill and had to be helped onto his horse. Fate intervened to turn the attack into a disaster. As soon as the French marched off a blizzard descended, causing all direction to be lost. Augereau’s corps followed the slope of the land and veered off to the left, away from Saint-Hilaire. Augereau’s advance struck the Russian line at the junction of its right and centre, coming under the fire of the blinded French artillery and then point-blank fire of the massive 70-gun Russian centre battery. Meanwhile, Saint-Hilaire’s division, advancing alone in the proper direction, was unable to have much effect against the Russian left.

Augereau’s corps was thrown into great confusion with heavy losses,[20] gives Augereau’s official tally[who?] of 929 killed and 4,271 wounded. One regiment, the 14th Ligne, was unable to retreat and fought to the last man, refusing to surrender; its eagle was carried off by Captain Marbot. Its position would be marked by a square of corpses.[21] Bennigsen took full advantage by falling on Saint-Hilaire’s division with more cavalry and bringing up his reserve infantry to attack the devastated French centre. Augereau and 3,000 to.4,000 survivors fell back on Eylau, where they were attacked by about 5,000 Russian infantry. At one point, Napoleon himself, using the church tower as a command post, was nearly captured, but members of his personal staff held the Russians off for just long enough to allow some battalions of the Guard to come up. Counterattacked by the Guard’s bayonet charge and Bruyère’s cavalry in its rear, the attacking Russian column was nearly destroyed.[22] For four hours, the French centre was in great disorder, virtually defenceless and in imminent danger.[23]

With his centre almost broken, Napoleon resorted to ordering a massive charge by Murat’s 11,000-strong cavalry reserve. Aside from the Guard, that was the last major unbloodied body of troops remaining to the French.

Cavalry charge painted by Jean-Antoine-Siméon Fort.Cavalry charge at Eylau

Cavalry charge painted by Jean-Antoine-Siméon Fort.Cavalry charge at Eylau

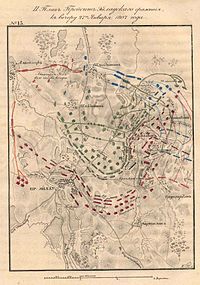

Battle of Eylau after Davout’s attack late in the day. French shown in red, Russians in green and Prussians in blue.

Battle of Eylau after Davout’s attack late in the day. French shown in red, Russians in green and Prussians in blue.