“First Victory — Then Defeat!”

The Union defeat at the first battle of Manassas set in motion the full-scale war effort that changed America.

A cannon on the battlefield at Manassas Battlefield National Park. Photo by Robert B. Mitchell.

A cannon on the battlefield at Manassas Battlefield National Park. Photo by Robert B. Mitchell.MANASSAS, Va. — The quiet of a muggy August morning belies the tumult that unfolded on this battlefield more than 160 years ago.

A handful of tourists and dog walkers stroll across the fields where Union and Confederate forces collided on July 21, 1861. On that day, Union forces commanded by Maj. Gen. Irvin McDowell confronted rebel troops led by Maj. Gen. G.T. Beauregard at Manassas Junction, a strategically significant railroad junction in western Prince William County, Va., in what was the first major battle of the Civil War.

No less than Gettysburg, Fredericksburg, Antietam, or indeed any number of Civil War battlefields, Manassas is a somber place — especially since it is the site of two significant battles, the second coming in 1862 and resulting in another Confederate victory.

Cannons and monuments abound, offering silent testimony to the courage, chaos, sacrifice and stampede that marked that fateful day in 1861. Few if any realized at the time that the battle foretold years of unimaginable carnage and — in ways totally unforeseen — immense change in American society that followed the Southern surrender at Appomattox almost four years later.

In the spring and summer of 1861, Union and Confederate forces positioned themselves in Washington and Northern Virginia. McDowell commanded the Union troops gathered in and around the nation’s capital while Beauregard led the Confederates massed near Manassas Junction.

Clamor for a quick and decisive strike against the rebels had been building in Washington since the fall of Fort Sumter in April. As spring gave way to summer, calls for action grew louder. Reporting that the decision had been made to take the fight to the rebels, the New York Tribune cheered what it expected would be a triumphant Union victory.

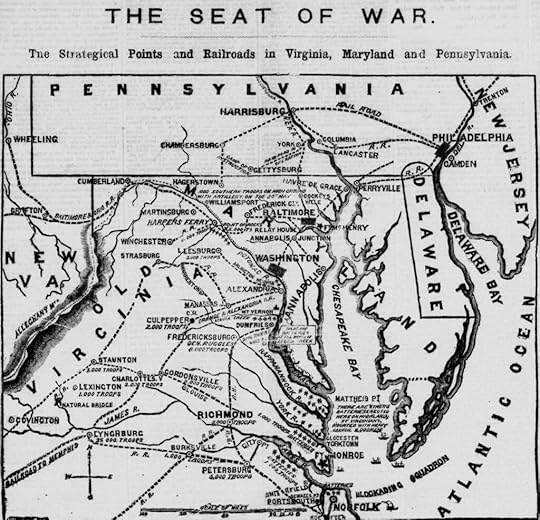

The New York Herald map from May 27, 1861, lays out the disposition of Union and Confederate forces in Virginia.

The New York Herald map from May 27, 1861, lays out the disposition of Union and Confederate forces in Virginia.“We congratulate the country,” a Tribune report from Washington proclaimed, that “the power of the government is about to be felt. Thousands of hearts, long despondent with sad forebodings of evil, in innumerable things, are about to be changed to joy unspeakable by the bugles of the charge. ‘Forward to Richmond! We seize the cry of the old crusader and shout with exultant voices, ‘God wills it! God wills it!'”

A sub-head on the Tribune story summed up the prevailing hubris: “On, to Richmond.”1

Northern politicians and newspapers like the Tribune expected that the rebel forces would be routed and secession crushed. It didn’t turn out that way.

The story of the battle is well known. Headquartered in Arlington on the estate of Confederate General Robert E. Lee, McDowell’s force of 30,000 began its march toward Manassas Junction on July 16. A journey that today takes less than an hour (if traffic cooperates) took four days as Union forces encountered fallen trees and other obstacles left by retreating Confederates. Meanwhile, rebel forces numbering about 25,000 under Beauregard waited at Manassas Junction.2

Well before dawn on July 21, McDowell went on the attack and outflanked the surprised Confederates. Rebels retreated until the Union advance halted in the face of withering artillery from troops led by Gen. Thomas L. Jackson — later known as “Stonewall” Jackson for his stand against the advancing U.S. forces. The Union delay gave Confederates the time to reorganize and launch a counterattack.

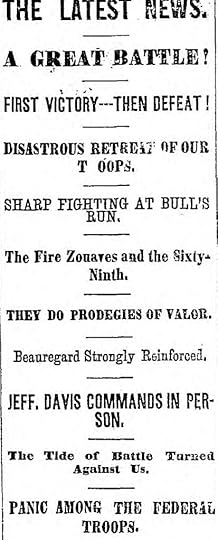

The Chicago Tribune, July 23, 1861.

The Chicago Tribune, July 23, 1861.Confederates benefited from the arrival of reinforcements under the command of General Joseph E. Johnston from the Shenandoah Valley. Union General Robert Patterson, a veteran of the War of 1812, was supposed to keep Johnston bottled up but failed to do so. Confused by unclear instructions from Washington, Patterson retreated to Harper’s Ferry. With the way open, Johnston’s troops departed from Winchester and arrived via railroad to reinforce Beauregard’s forces.3

Stalled before the strengthened rebel defenses, exhausted and disorganized Union troops withdrew and then retreated in panic as Confederates advanced. Picnicking Washingtonians who traveled to the scene of the battle hoping to see a stirring martial spectacle found themselves caught up in the frenzied retreat.

The confusion on the battlefield was reflected in the headlines that appeared over the next several days in the Northern press. Early reports hailed a great Union victory. The next day, the picture became clearer. “FIRST VICTORY — THEN DEFEAT!” shouted the page 1 headline in the Chicago Tribune. Sub-heads elaborated on the sobering details. “The Tide of Battle Turned Against Us,” and “Panic Among the Federal Troops.”4

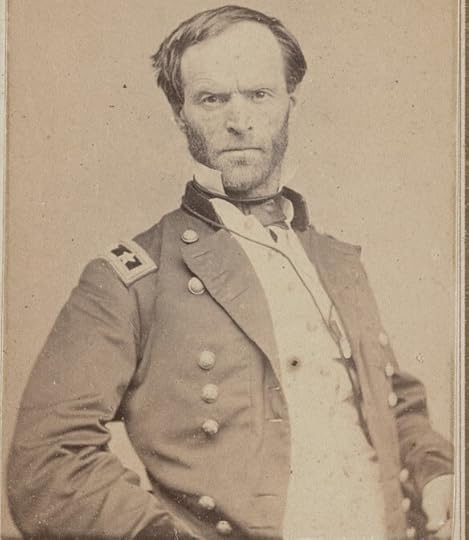

William Tecumseh Sherman, then a colonel commanding a New York brigade in the battle, wrote in his memoirs that the Union defeat exposed the inexperience, complacency, disorganization, and hubris of the Northern army.

“Our men had been told so often at home that all they had to do was make a bold appearance, and the rebels would run,” Sherman recalled. Almost “all of us for the first time then heard of cannon and muskets in anger, and saw the bloody scenes common to all battles, with which we were soon to be familiar. We had good organization, good men, but no real cohesion, no real discipline, no respect for authority, no real knowledge of war.”

While the Union defeat humiliated the North, the battle also revealed that the Confederates were too disorganized to pursue their fleeing enemy. The rebels “really had not much to boast of,” according to Sherman, “for in three or four hours of fighting their organization was so broken up that they did not and could not follow our army, when it was known to be in a state of disgraceful and causeless flight.”5

Both sides learned lessons that shaped the rest of the war. Congress approved legislation to enlist 1 million men for a period of three years. President Abraham Lincoln called in General George McClellan from the west to take command of the new troops who would be organized into the Army of the Potomac. McClellan melded this martial multitude into a powerful fighting force that he would prove strangely reluctant to use but which under the leadership of Ulysses S. Grant eventually crushed the rebellion after years of hard and bloody fighting. Reveling in their victory at Manassas, Confederate troops gained a confidence in their fighting ability that fortified them in the years ahead.6

William Tecumseh Sherman. Library of Congress.

William Tecumseh Sherman. Library of Congress.In Washington, the aftermath of the Union defeat produced a profound change in policy. During the opening months of the war, many in the North wanted to prosecute the war simply to restore the Union without disturbing slavery where it existed. After Manassas, Congress took the first, tentative steps toward abolition by passing legislation allowing Union forces to free enslaved men and women who were being used to aid the Confederate war effort.

After the defeat at Manassas, the North learned “that if the National Government did not interfere with slavery, slavery would interfere with the National Government,” James G. Blaine wrote in the first volume of his Twenty Years of Congress. The reluctance to confront enslavement began to give way to the realization that it was a central pillar of rebellion and secession.

“The virtue of this legislation,” Blaine argued, “consisted mainly in the fact that it exhibited a willingness on the part of Congress to strike very hard blows and to trample the institution of slavery whenever or wherever it should be deemed advantageous to the cause of the Union to do so. From that time onward the disposition to assail slavery was rapidly developed …”7

Lincoln would issue the Emancipation Proclamation Jan. 1, 1863. The Thirteenth Amendment abolishing slavery passed Congress in January 1865 and was ratified before the end of the year. Slowly but surely, the war that began simply to preserve the Union would also become a war to end slavery.

The Manassas battlefield, Aug. 4, 2024. Photo by Robert Mitchell.New York Tribune June 29th, 1861, p. 4.

The Manassas battlefield, Aug. 4, 2024. Photo by Robert Mitchell.New York Tribune June 29th, 1861, p. 4.  ︎W.J. Tenney, The Military and Naval History of the Rebellion in the United States (New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1866) p. 69; James McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (New York, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988), p. 339. Hereafter referred to as McPherson; Bruce Catton, The Coming Fury (Garden City, New York, Doubleday & Co., 1961), p. 440.

︎W.J. Tenney, The Military and Naval History of the Rebellion in the United States (New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1866) p. 69; James McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (New York, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988), p. 339. Hereafter referred to as McPherson; Bruce Catton, The Coming Fury (Garden City, New York, Doubleday & Co., 1961), p. 440.  ︎McPherson, p. 339.

︎McPherson, p. 339.  ︎Chicago Tribune, July 23, 1861, p. 1.

︎Chicago Tribune, July 23, 1861, p. 1.  ︎William T. Sherman, Memoirs of General William T. Sherman, Vol. 1 (New York D. Appleton & Co., 1875, pp. 181-182. Hereafter referred to as Sherman.

︎William T. Sherman, Memoirs of General William T. Sherman, Vol. 1 (New York D. Appleton & Co., 1875, pp. 181-182. Hereafter referred to as Sherman.  ︎McPherson, pp. 348-349..

︎McPherson, pp. 348-349..  ︎James G. Blaine, Twenty Years of Congress, Vol. 1 (Norwich, Conn.: The Henry Bill Publishing Company, 1884), pp. 341-343.

︎James G. Blaine, Twenty Years of Congress, Vol. 1 (Norwich, Conn.: The Henry Bill Publishing Company, 1884), pp. 341-343.  ︎

︎_____

I am the author of the forthcoming The Partisans: James G. Blaine, Roscoe Conkling, and the Politics of Rivalry and Revenge in the Gilded Age (Edinborough Press).

My other books are available at amazon. com

Congress and the King of Frauds: Corruption and the Credit Mobilier Scandal at the Dawn of the Gilded Age.

Congress and the King of Frauds: Corruption and the Credit Mobilier Scandal at the Dawn of the Gilded Age.

Skirmisher: The Life, Times, and Political Career of James B. Weaver.

Skirmisher: The Life, Times, and Political Career of James B. Weaver.