Robert B. Mitchell's Blog

October 29, 2025

The Garfield I have come to know

With Netflix about to release its series on James A. Garfield, I offered my take on the slain president on Substack.

https://robertbmitchell.substack.com/p/the-garfield-i-have-come-to-know?r=24m05h

September 21, 2025

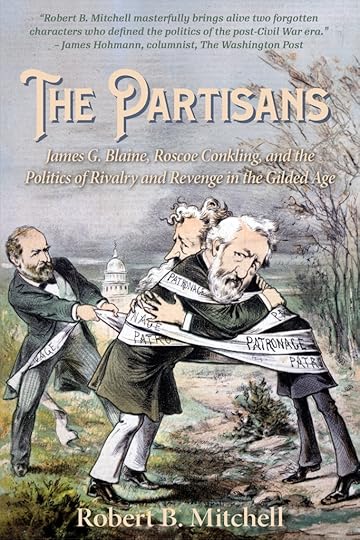

Blaine, Conkling, and power

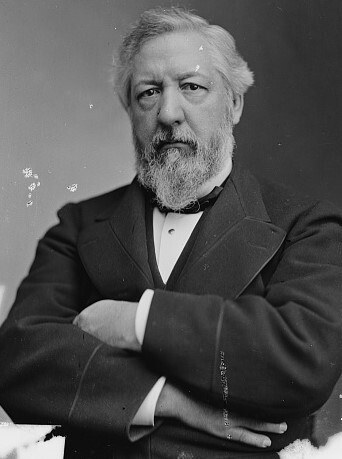

The two very different Gilded Age Republican politicians practiced their craft in distinctive ways. One showed the way to the future.

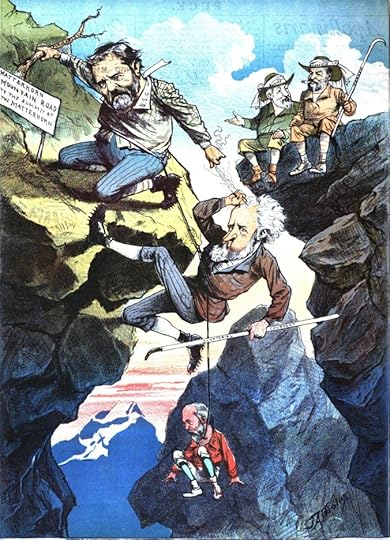

A cartoon from Puck shows Ulysses S. Grant, Roscoe Conkling, and Tom Platt dangling above an Alpine crevice as President James A. Garfield and Secretary of State James G. Blaine (upper right) contentedly look on.

A cartoon from Puck shows Ulysses S. Grant, Roscoe Conkling, and Tom Platt dangling above an Alpine crevice as President James A. Garfield and Secretary of State James G. Blaine (upper right) contentedly look on.For many reasons, the Gilded Age feud between Republicans James G. Blaine of Maine and Roscoe Conkling of New York marked a watershed chapter in American politics.

Their 18-year rivalry determined the leadership of the Republican Party as the United States recovered from the Civil War and evolved from an agrarian economy into an industrial powerhouse. They battled each other to a draw at presidential nominating conventions in 1876 and 1880 before Republicans finally turned to Blaine as their nominee in 1884. Their ferocious infighting over patronage and clout in the administration of President James A. Garfield ended when a gunman, inflamed by the feud, fatally shot the president.

But the significance of the Blaine-Conkling feud had as much to do with the manner in which they practiced their craft as the momentous confrontations that dominated their careers. From the moment in 1866 when Blaine antagonized Conkling by mocking the New Yorker’s “grandiloquent swell and “overpowering turkey-gobbler strut,” it was clear that they took vastly different approaches to the business of gaining and cultivating power and influence.

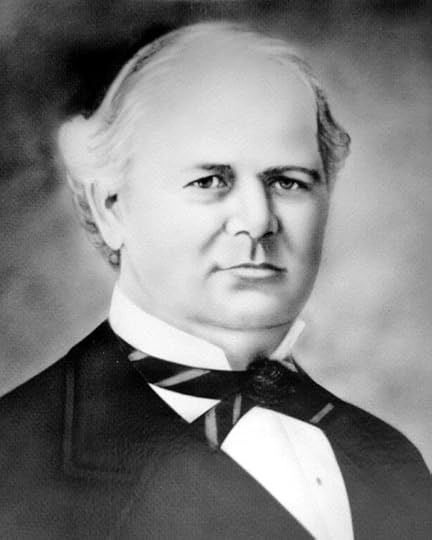

Personality in large measure shaped their different political styles. Blaine was an early and skilled practitioner of retail politics. Personable and affable, he possessed a photographic memory that enabled him to make acquaintances feel like friends by remembering personal details and circumstances. He could explode when provoked, as his exchange with Conkling demonstrated, but such outbursts were rare.

Blaine in Puck.

Blaine in Puck.During his decades-long career in politics, Blaine’s personal charisma and charm enabled him to assemble a loyal cadre of supporters across the country. One of his many admirers told Brooklyn Eagle correspondent Billy Hudson: “He is irresistible. I defy anyone, Republican or Democrat, to be in his company for half an hour and go away anything else than a personal friend.”1

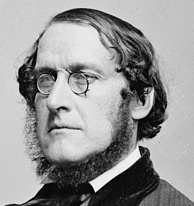

Conkling, on the other hand, belonged to that curious subset of politicians who preferred not to deal with people. When backslapping and glad-handing were required, as when he mounted his first campaign for the Senate in 1867, he could force himself to be sociable. When Black Mississippi Republican Blanche Kelso Bruce was ignored on the Senate floor in 1875 as he presented his credentials, Conkling introduced himself, extended his arm, and escorted his fellow Republican to the clerk’s desk.

But such displays were rare. Truculence was Conkling’s default setting. Where Blaine built a devoted personal following with charisma and charm, Conkling kept allies at arm’s length and alienated subordinates with his imperious personality. He sparred in the boxing ring to stay in shape. He was rumored to carry a gun on the Senate floor. He delighted in skewering enemies in debate and intimidating underlings. The press dubbed him “Lord Roscoe.” “Without malignity,” journalist George Alfred Townsend wrote in 1872, “Conkling is nothing.”2

Roscoe Conkling in Puck.

Roscoe Conkling in Puck.As significant as these personal differences were, a more important factor separated Blaine and Conkling as they fought for power. For the first time, politicians could reach voters — and gain insights into public opinion — through advances in technology that made it possible for news to be disseminated more widely and more quickly than ever before.

Ahead of the invention of the telephone, and long before radio, TV, and the internet, the era of mass media began on the printed page as newspapers sprouted from New England to California. By 1870, more than 5,000 dailies and weeklies served readers in county seat towns and big cities. Small towns could support two newspapers that catered to Democrats or Republicans, while in big cities, more than 150 dailies claimed circulation in excess of 10,000. The telegraph brought news from Washington, where dozens of correspondents kept hometown readers apprised of news from Capitol Hill and the White House. Advances in printing technology enabled newspapers to print tens of thousands of copies an hour, many of which were widely distributed via the railroad.3

Blaine was uniquely equipped — by experience and facility with words — to take advantage of the rising power of the press. Before entering politics, he worked as an editor on newspapers in Augusta and Portland, Maine. Blaine “was especially fitted for the field of journalism,” biographer Theron Clark Crawford wrote. “He had a keen sense of the public’s wants, and through this sense was close in sympathy with the popular will. He had the experienced and successful editor’s ability to recognize the leading topic of the moment.”4

While it did not insulate him from negative headlines, Blaine’s relationship with the press worked to his advantage — and he knew it. “Oh, I’m one of them myself, and I like the breed of dogs,” Blaine said of the correspondents who wrote about him. “Besides, it is a better thing to have the boys who write about you dip their pens in the ink of friendship than that of gall.”5

Clark noted that, in at least one instance, Blaine’s relationship with the press went beyond friendship. Blaine wrote anonymously for the New York Tribune and was widely believed to have been the author of an editorial published by the paper in 1881 regarded as a declaration of war by the Garfield administration against Empire State Stalwarts aligned with Conkling.

While Blaine cultivated his relationship with the press, Conkling kept correspondents at arm’s length and menaced editors. When a Washington newspaper was poised to print an article about Conkling’s extramarital affairs, Conkling stormed into the office, demanded to see the article, and then threatened to kill the editor if he published the story.

Lord Roscoe cared enough about press management to share texts of his major speeches with correspondents but showed nothing of Blaine’s flair for cultivating relationships with them. As he fought to be returned to the Senate after dramatically resigning in 1881, Conkling summoned a correspondent from the New York Herald to declaim about Blaine’s malevolence and demand that the Herald print an article attacking Garfield for duplicity regarding management of the Port of New York, the patronage bastion which served as the basis of Conkling’s political strength.

The Herald obliged, but it was too late. The vast majority of New York newspapers had already gone on record supporting Garfield.6 In the years to come, the savviest politicians in both parties emulated Blaine’s approach to dealing with the press.

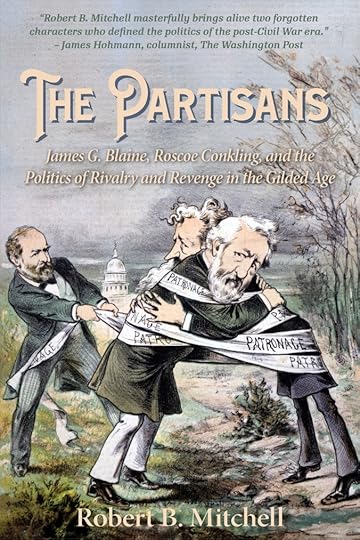

The Partisans: James G. Blaine, Roscoe Conkling, and the Politics of Rivalry and Revenge in the Gilded Age, is now available for pre-order at amazon.com.William C. Hudson, Random Recollections of an Old Political Reporter (New York: Cupples & Leon Co., 1911), p. 128. Hereafter referred to as Hudson.

The Partisans: James G. Blaine, Roscoe Conkling, and the Politics of Rivalry and Revenge in the Gilded Age, is now available for pre-order at amazon.com.William C. Hudson, Random Recollections of an Old Political Reporter (New York: Cupples & Leon Co., 1911), p. 128. Hereafter referred to as Hudson.  ︎“Gath” (the pen name of George Alfred Townsend), “Washington,” Chicago Tribune, Dec. 31, 1872, p. 2.

︎“Gath” (the pen name of George Alfred Townsend), “Washington,” Chicago Tribune, Dec. 31, 1872, p. 2.  ︎Mark Wahlgren Summers, The Press Gang: Newspapers & Politics 1865-1878 (University of North Carolina Press, 1994, pp. 10-13).

︎Mark Wahlgren Summers, The Press Gang: Newspapers & Politics 1865-1878 (University of North Carolina Press, 1994, pp. 10-13).  ︎Theron Clark Crawford, James G. Blaine. A Study of His Life and Career (Edgewood Publishing Co., 1893), pp. 36-37.

︎Theron Clark Crawford, James G. Blaine. A Study of His Life and Career (Edgewood Publishing Co., 1893), pp. 36-37.  ︎Hudson, p. 128.

︎Hudson, p. 128.  ︎Alan Peskin, Garfield (The Kent State University Press, 1978), pp. 569-570.

︎Alan Peskin, Garfield (The Kent State University Press, 1978), pp. 569-570.  ︎

︎

August 13, 2025

A New Orbit: John A. Logan, a Republican “developed by the war”

The war to save the Union supercharged John A. Logan’s evolution from Douglas Democrat to Radical Republican. Third in a series about Gilded Age party switchers.

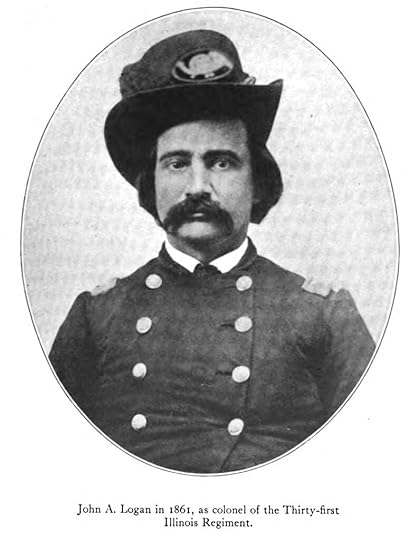

Photo and caption from Mary Logan’s Reminiscences of a Soldier’s Wife.

Photo and caption from Mary Logan’s Reminiscences of a Soldier’s Wife.One of the most dramatic political transformations of the Gilded Age involved an obscure Democratic member of Congress who championed the Fugitive Slave Act and denounced Abolitionists before becoming one of the leading members of the Republican Party.

John Alexander Logan of Illinois was a black-haired attorney elected to Congress in 1858 to represent Illinois’s southernmost congressional district, where Southern sympathies and antipathy toward enslaved Black people ran high. On Capitol Hill and back home, “Black Jack” Logan established himself as a disciple of Senator Stephen A. Douglas, an apostle of the Fugitive Slave Act, and a virulent critic of the Republican Party. By the time of his death in 1886, Logan ranked among the nation’s most prominent Republicans.

A variety of motives drove the party-switchers of the Gilded Age as they searched for what Iowa populist James B. Weaver called a “new orbit.” Becoming politically active in the 1850s, when anti-slavery Democrats joined like-minded Whigs to form the Republican Party, Weaver anticipated and worked for a similar realignment of reform-minded politicians in the decades after the Civil War. He returned to the Democratic Party in the early 20th century when he concluded that William Jennings Bryan offered the best hope for leading a reform movement to power.

Benjamin Butler of Massachusetts left the Democratic Party and embraced the agenda of radical Republicans. As the 1870s continued, Butler broke irrevocably with Republicans over monetary policies that he believed favored the interests of bankers and Wall Street over average citizens. He made a brief return to the Democratic Party before running for president in 1884 at the head of the Greenback ticket. Late in life, Butler described himself as a believer in Hamiltonian means — that is, the vigorous use of federal power — to pursue the Jeffersonian ends of protecting the rights and interests of average citizens.

Logan’s evolution from loyal Democrat to radical Republican began in response to changing political realities and was supercharged by battle. “Logan was developed by the war,” the Chicago Tribune wrote at his death in 1886. “The cavalry bugler sounded the keynote of his character, and in an atmosphere of dust and powder he grew great.”1

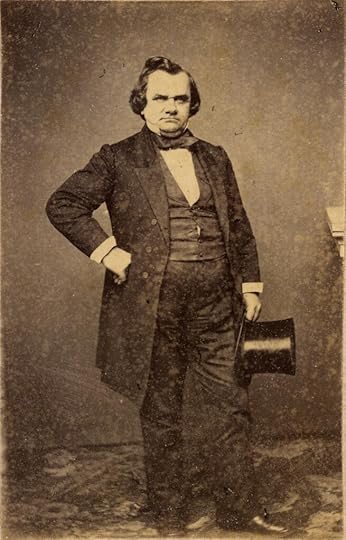

Senator Stephen A. Douglas. Library of Congress.

Senator Stephen A. Douglas. Library of Congress.Few observers would have predicted greatness for Logan before the war, when his shrill defenses of the Fugitive Slave Act and partisan denunciations of Lincoln earned him notoriety in the Northern press.

“Every fugitive that has been arrested in Illinois, or in any of the western states — and I call Illinois a western state because I am ashamed longer to call it a northern state — has been made by Democrats,” Logan told the House on Dec. 9, 1859.

He disparaged “Abolitionist hordes” in the northern part of the state who made it impossible to enforce the infamous Fugitive Slave Act that treated escapees from bondage as the missing property of enslavers. “In Illinois Democrats have all that work to do. You call it the dirty work of the Democratic Party to catch fugitive slaves for southern people. We are willing to perform that dirty work. I do not consider it disgraceful to perform any work, dirty or not dirty, which is in accordance with the laws of the land and the Constitution of the country, and calculated to assist men in recovering that which is their right, guaranteed to them under the Constitution and the laws of the land.”2

The Chicago Tribune and other Republican newspapers promptly dubbed the Southern Illinois Democrat “Dirty Work Logan.”3

Two years later, after Logan characterized Abraham Lincoln as a “strictly sectional candidate” whose election would trigger the conflict feared by all, a friendly constituent chastised him in a letter published by the Illinois Journal in Springfield. Abandon the partisan rhetoric giving aid and comfort to Southern fire-eaters, the letter urged Logan, and rise to the defense of your country.

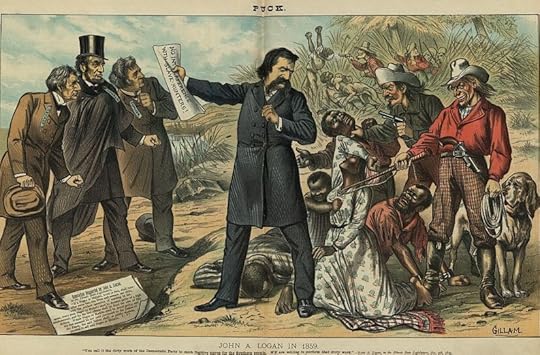

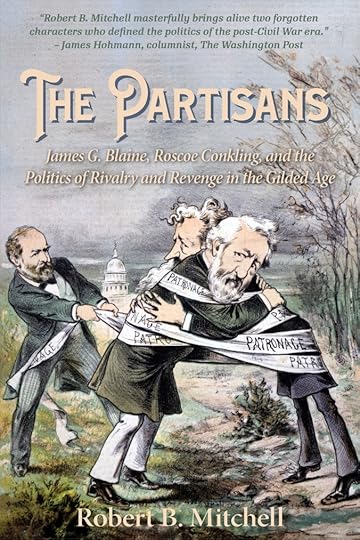

Puck dramatizes Logan’s infamous promise in 1859 that Democrats were willing to do to the “dirty work” of capturing Black escapees from enslavement.

Puck dramatizes Logan’s infamous promise in 1859 that Democrats were willing to do to the “dirty work” of capturing Black escapees from enslavement.“You are a young man,” Logan was advised. “If you will, you have a fine career opening up before you; and now, with your position, in this crisis, you have a golden opportunity to make your mark, and take your stand among the true patriots and statesmen of our country’s history, which, once let slip, will never recur again.”4

It was good advice, but Logan wasn’t ready to act on it. In Chicago on May 20, Douglas thundered that “there are no neutrals in this war, only patriots and traitors.” Struggling to remain impartial regarding the looming sectional conflict, Logan reacted with fury to the analysis of his ally and mentor. Meanwhile, unfavorable newspaper coverage and growing pro-Union sentiment in his district Logan’s position increasingly untenable.5

The New York Herald reported from Cairo, Ill., on June 12 that Logan — along with members of his family — was plotting to “separate Southern Illinois from the remainder of the state” to support the Confederacy. The story was false, but it was followed by critical commentary closer to home. Less than a week later, the Daily Illinois State Journal in Springfield noted that pro-Union “Egyptian Home Guard” called for Logan’s resignation from Congress. “There seems to be,” the newspaper observed, “a general uncertainty as to the exact ‘sentiments’ of Mr. Logan.”6

Logan needed to get on the right side of rapidly hardening pro-Union sentiment in Illinois. He soon got his chance.

On June 19, Grant bumped into Logan and another Democratic congressman from Illinois, John McClernand, in Illinois’s capital city. The encounter coincided with a critical moment in the mobilization for war. Short-term enlistments in the state militia were expiring, and the troops Grant was training were being asked to sign up for three years of service in the U.S. Army.

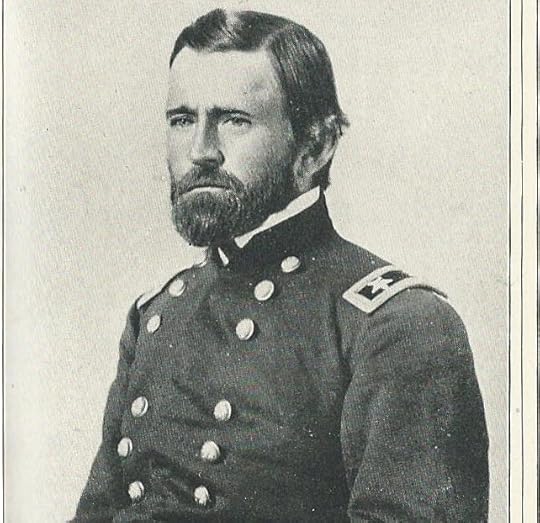

Ulysses S. Grant, before Vicksburg.

Ulysses S. Grant, before Vicksburg.Grant was asked if the lawmakers could address his troops. He welcomed a speech from McClernand, whose pro-Union sentiments were undeniable. Logan was another matter. Grant had noted Logan’s ambivalence about who was to blame for the war and the criticism directed at him by the Republican press. Some editors, Grant wrote, “were very bitter in their denunciations of his silence.”

Grant need not have worried. Logan defended the Stars and Stripes with passion and eloquence.

“Officers and men gathered in front of the grandstand in the free and easy democratic way characteristic of your true militiaman, and Logan made us a ringingly loyal speech,” one witness recalled. Logan’s oration “has he had hardly equaled since in force and eloquence,” Grant remembered in his memoirs. “It breathed a loyalty and devotion to the Union which inspired my men to such a point that they would have volunteered to remain in the army as long as an enemy of the country threatened to bear arms against it. They entered the United States service almost to a man.”7

The speech represented a watershed moment in Logan’s career. As neutrality gave way to support for the Union, his rise to greatness had begun.

Logan returned to Washington and witnessed the Union debacle at the first battle of Manassas. Back in Illinois, he raised an infantry regiment after a stirring speech at Marion in which he declared “The time has come when a man must be for or against his country, not for or against his state. … I for one will stand or fall for this Union, and shall this day enroll for the war. I want as many of you as will to come with me. If you say ‘No,’ and see the best interests of your homes and your children in another direction, may God help you.”8

Logan’s speech roused the crowd gathered to hear him and highlighted the shifting views in a region that once tilted toward the Confederacy. But not everyone was similarly swayed. The war cleaved Logan’s family. His mother vowed never to speak to him. His sister volubly denounced Logan as he marched past in Murphysboro, Ill., prompting Logan’s wife, Mary, to throw a punch and a chair at her sister-in-law.9

Logan joined Grant’s push south along the Mississippi and fought with his regiment at Belmont and Fort Donelson, where his troops “fought like veterans who had never had any other occupation” and he was wounded. While recovering, Logan was promoted to the rank of brigadier general.10

Over the next two years, he served with distinction as Grant tightened his stranglehold on the Confederacy. Whatever hesitancy he once had about the Union cause evaporated in the heat of combat. “We constitute the military arm of the Government,” he told his troops in February 1863. Duty required them to defend the “temple of Liberty” as it was being “shaken to the very center by the ruthless blows of traitors who have desecrated our flag” and “destroyed our peace.” 11

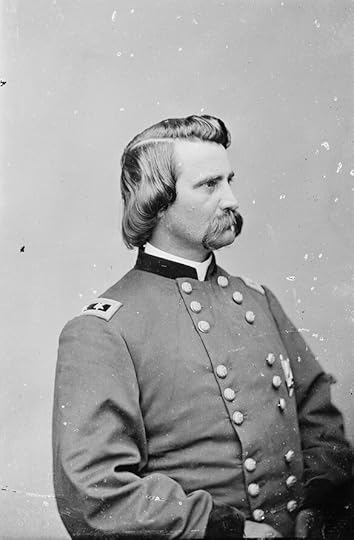

Gen. John A. Logan in uniform. Library of Congress.

Gen. John A. Logan in uniform. Library of Congress.Logan’s performance in combat earned a salute from the Chicago Tribune. The newspaper that labeled him “Dirty Work Logan” before war hailed his service and evolution into a wholehearted champion of the Union. The Tribune declared that “since this war broke out, and since Gen. Logan assumed the patriot’s part, and pushed gallantly into the thickest and hottest of the fight, we have conceived and expressed admiration for his qualities as a man and a lover of his country that we have never felt before.”

The Tribune remained uncertain about his partisan loyalties. But there was no doubt about his devotion to the Union cause:

Earnest, ready, untiring, vigilant, full of pluck, abounding in patriotism, confident of final success, and willing, whether success or failure comes, to do his whole duty because his country commands, he has become the pet and boast of the army to which he belongs; and we only re-echo the opinion of his superior, when we say that ‘he is a whole division in himself.'” 12

Not everyone in uniform shared the newspaper’s admiration. General William Tecumseh Sherman regarded Logan and General Frank P. Blair Jr. with skepticism. They possessed “great courage and talent,” Sherman wrote in his memoirs, but were “politicians by nature and experience” viewed with scorn by regular officers. After the death of General William McPherson in 1864 as Union forces closed in on Atlanta, Sherman declined to appoint Logan as McPherson’s successor to lead the Army of the Tennessee.

An astute judge of character, Sherman saw that the war for Logan was simultaneously a military and political conflict and did not approve of the commingled priorities. He noted with displeasure that after the Union capture of Atlanta, Logan and Blair “went home to look after politics.”13

Logan’s decision to return home and campaign for Abraham Lincoln’s re-election in 1864 marked a crucial step in his political journey. His days as a Democrat were over. “There are no party ties to bind me now,” he declared in a lengthy speech delivered in Carbondale on Oct. 1. “The only ties I acknowledge are those that bind me to the Stars and Stripes.” Logan emphasized preservation of the Union and made no reference to enslavement. He reviled so-called Peace Democrats who favored accommodation with secessionists to end the war. Acknowledging that he opposed Lincoln’s election in 1860, Logan now supported his re-election because “he has endeavored to sustain the government honestly and faithfully.”

The next step was inevitable. After the war, Logan joined the Republican Party and was elected to Illinois’s at-large seat in Congress. With senators chosen then by state legislators, the election made the already well-known general the only directly elected statewide member of Illinois’s congressional delegation.

The votes had barely been counted when reports appeared in the press linking Logan to plans to impeach President Andrew Johnson. Logan quickly denied any involvement in impeachment efforts,14 but the rumors highlighted the fraught political environment in Washington and foreshadowed Logan’s partisan posture.

Back on Capitol Hill for the first time since he resigned his House seat in 1862, Logan aligned himself with Republican radicals who favored a sweeping overhaul of Southern society that would guarantee once-enslaved Black men and women civil and political rights. Campaigning for Republicans in Ohio in 1867, he made the then-controversial case for extending the right to vote for formerly enslaved Black men by linking it to the military experience of white Union Army veterans:

“You will remember the times we were called to go against rebel bayonets; you remember the many battles through which you have passed, and you ought to remember … the men at the South who were your friends. … Now I appeal to you as honest men if you ever saw a Black man [in the] South who was not loyal to the government?15

In addition to informing Logan’s views on Reconstruction, honoring the memory of the war became a personal cause and provided an important source of political muscle. In May 1866, Logan spoke at a “Decoration Day” observance at a Carbondale, Ill., military cemetery that numbered among the ceremonies that led to the annual observance of the Memorial Day holiday honoring fallen veterans of U.S. wars. He belonged to the Society of the Army of the Tennessee and joined the new Grand Army of the Republic in 1866. As commander of the GAR in 1868, Logan ordered local chapters to decorate the graves of fallen Union soldiers on May 30.16

Logan’s Memorial Day directive followed another noteworthy order issued earlier in the year. In the tense days that followed President Andrew Johnson’s firing of Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, Logan ordered GAR members to stand guard around the White House and War Department, and he offered Stanton more than 100 veterans who would act as a personal guard. Stanton declined the offer.17 Logan served as one of the House prosecutors during Johnson’s impeachment trial in the Senate.

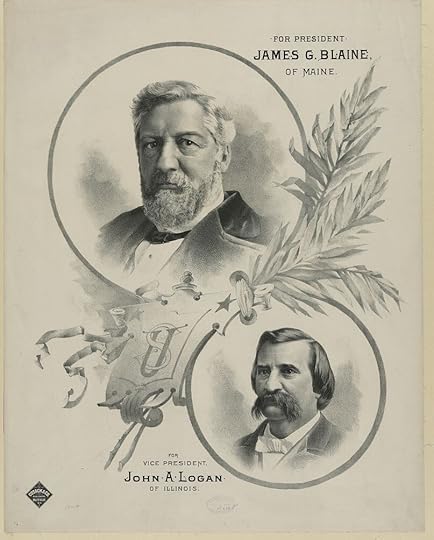

Logan remained a prominent national figure through the Grant administration and into the 1880s. He joined Republican “Stalwarts” led by Sens. Roscoe Conkling of New York and J. Donald Cameron of Pennsylvania in the unsuccessful effort to nominate Grant at the 1880 Republican convention in Chicago for an unprecedented third term as president. Four years later, Logan sought the nomination himself but ended up as the party’s vice-presidential candidate on the ticket with James G. Blaine.

Logan ran on the 1884 Republican ticket as vice-presidential candidate with James G. Blaine. Library of Congress.

Logan ran on the 1884 Republican ticket as vice-presidential candidate with James G. Blaine. Library of Congress.At his death in 1886, the New York Times reminded readers for whom the Civil War was a fading memory that the conflict remained “the most signal event” in the memory of millions of their fellow citizens. For them, Logan’s appeals to patriotism were genuine — and compelling.

“It is easy for those who knew Gen. Logan only as a politician and Republican leader in the House and Senate to feel that his prominence, his influence, his unquestioned popularity, were a curious evidence of an unreasoning bias in the partisan mind,” the Times acknowledged. But for the generation of men and women who “shared the stress of that sore trial in which he cast his lot with the Union, and who remember also to what deep passion of patriotism his heroic service appealed during those four years, the charm of his name is no mystery.”18

“The Life of Gen. Logan: a sketch of the dead soldier-statesman’s career,” Chicago Tribune, Dec. 27, 1886, p. 3. ︎U.S. Congress, House, Congressional Globe, Thirty-Sixth Congress, Dec. 9, 1859, p. 85.

︎U.S. Congress, House, Congressional Globe, Thirty-Sixth Congress, Dec. 9, 1859, p. 85.  ︎“Egypt in Congress,” Chicago Tribune, Dec. 12, 1859, p. 2.

︎“Egypt in Congress,” Chicago Tribune, Dec. 12, 1859, p. 2.  ︎“To John A. Logan,” Illinois Journal, Feb. 15, 1861, p. 1.

︎“To John A. Logan,” Illinois Journal, Feb. 15, 1861, p. 1.  ︎Gary Ecelbarger, Black Jack Logan: An Extraordinary Life in Peace and War (Guilford, Conn., The Lyons Press, 2005), p. 73. Hereafter referred to as Ecelbarger.

︎Gary Ecelbarger, Black Jack Logan: An Extraordinary Life in Peace and War (Guilford, Conn., The Lyons Press, 2005), p. 73. Hereafter referred to as Ecelbarger.  ︎“The Seat of War at the West,” New York Herald, June 12, 1861, p. 5; “Egypt Speaks for the Union. What Position does John Logan Occupy?” Daily Illinois State Journal, June 18, 1861, p. 2.

︎“The Seat of War at the West,” New York Herald, June 12, 1861, p. 5; “Egypt Speaks for the Union. What Position does John Logan Occupy?” Daily Illinois State Journal, June 18, 1861, p. 2.  ︎Ecelbarger, pp. 78-79; U.S. Grant, Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant (New York: Da Capo Press, 1982), p. 125.

︎Ecelbarger, pp. 78-79; U.S. Grant, Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant (New York: Da Capo Press, 1982), p. 125.  ︎Mary Simmerson Cuninngham Logan, Reminiscences of a Soldier’s Wife (New York: C. Scribner’s and Sons, 1913, p. 98). Hereafter referred to as Mary Logan.

︎Mary Simmerson Cuninngham Logan, Reminiscences of a Soldier’s Wife (New York: C. Scribner’s and Sons, 1913, p. 98). Hereafter referred to as Mary Logan.  ︎Ecelbarger, pp. 88-89.

︎Ecelbarger, pp. 88-89.  ︎“The Ft. Donelson Victory,” Chicago Tribune, Feb. 18, 1862, p. 1; Ibid., “The Latest News by Telegraph,” March 22, 1862.

︎“The Ft. Donelson Victory,” Chicago Tribune, Feb. 18, 1862, p. 1; Ibid., “The Latest News by Telegraph,” March 22, 1862.  ︎Ibid., “The Voice of Patriotism,” Chicago Tribune, Feb. 21, 1863.

︎Ibid., “The Voice of Patriotism,” Chicago Tribune, Feb. 21, 1863.  ︎Ibid., “Gen. John A. Logan,” May 27, 1863, p. 2

︎Ibid., “Gen. John A. Logan,” May 27, 1863, p. 2  ︎William T. Sherman, Memoirs of General William T. Sherman, Vol. 2 (New York: Appleton & Co., 1886), pp. 85, 130.

︎William T. Sherman, Memoirs of General William T. Sherman, Vol. 2 (New York: Appleton & Co., 1886), pp. 85, 130.  ︎After Illinois had been awarded an additional seat in the House in 1862, the state legislature created an “at-large” House seat rather than redraw its existing 13 congressional districts. “Congressman At Large,” New York Tribune, Nov. 14, 1866, p. 4; Ibid., Nov. 23, 1866, p. 4.

︎After Illinois had been awarded an additional seat in the House in 1862, the state legislature created an “at-large” House seat rather than redraw its existing 13 congressional districts. “Congressman At Large,” New York Tribune, Nov. 14, 1866, p. 4; Ibid., Nov. 23, 1866, p. 4.  ︎Ecelbarger, p. 246; “Earnest Words from Gen. Logan,” Nashville, Ill., Journal, Oct. 4, 1867, p. 4.

︎Ecelbarger, p. 246; “Earnest Words from Gen. Logan,” Nashville, Ill., Journal, Oct. 4, 1867, p. 4.  ︎Ecelbarger, pp. 236-238; “Memorial Day: The Origins of Memorial Day,” U.S. Army Center of Military History [https://history.army.mil/Research/Ref...]

︎Ecelbarger, pp. 236-238; “Memorial Day: The Origins of Memorial Day,” U.S. Army Center of Military History [https://history.army.mil/Research/Ref...]  ︎David O. Stewart, Impeached (New York: Simon & Schuster Paperbacks, 2009), p. 141.

︎David O. Stewart, Impeached (New York: Simon & Schuster Paperbacks, 2009), p. 141.  ︎“John A. Logan,” New York Times, Dec. 27, 1886, p. 4.

︎“John A. Logan,” New York Times, Dec. 27, 1886, p. 4.  ︎

︎ Coming Oct. 1: The Partisans: James G. Blaine, Roscoe Conkling, and the Politics of Rivalry and Revenge in the Gilded Age. Published by Edinborough Press.

Coming Oct. 1: The Partisans: James G. Blaine, Roscoe Conkling, and the Politics of Rivalry and Revenge in the Gilded Age. Published by Edinborough Press.

July 29, 2025

And now a word from our sponsor

The Partisans: James G. Blaine, Roscoe Conkling, and the Politics of Rivalry and Revenge is set to go on sale Oct. 1. Here’s a brief video explaining the origins of their feud.

June 3, 2025

“A new orbit”: The unique political compass of Benjamin F. Butler

Colorful and controversial, the mercurial lawyer from Lowell, Mass., pursued a political career governed by a synthesis of Hamiltonian and Jeffersonian principles. The second installment in an occasional series on Gilded Age party-switchers.

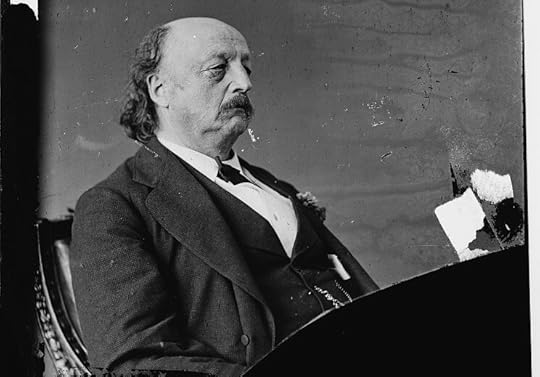

Benjamin F. Butler. Brady-Handy photograph collection, Library of Congress.

Benjamin F. Butler. Brady-Handy photograph collection, Library of Congress.Nobody could mistake Benjamin Franklin Butler of Massachusetts for a run-of-the-mill politician, not even in the 19th century.

He was born cross-eyed. His left eyelid drooped. Black hair tumbled from the back of his balding head. When he walked up the aisle in the House of Representatives, his stride was likened to a “bass walking on its tail.” He delighted in discord and demonstrated a genius for creating — and thriving in — controversy.

“General Butler was not eloquent, but he was savage — savage as a meat ax,” Republican representative Julius Caesar Burrows of Michigan recalled, referring to Butler by his Civil War rank. “It was not what he said that made the House always listen to him with rapt attention, but the expectation of what he was going to say. He was like a volcano — always smoking and always giving a hint of an impending eruption.”1

Butler stood out not only because of his unique appearance and proclivity for political pugilism but because he charted a dramatically unconventional partisan path. Before the Civil War, the lawyer from Lowell was a Democrat allied with Jefferson Davis of Mississippi, the future president of the Confederacy. When war broke out, Butler distinguished himself as an ardent Union loyalist whose refusal to return Black people to their Southern enslavers opened the door for Black men to serve in the Union Army. Davis, his one-time ally, called for Butler’s execution after Butler declared that women in New Orleans who insulted Northern soldiers would be treated as prostitutes.2

Butler became a prominent Republican radical in Congress after the war but returned to the Democratic Party to win election as governor of Massachusetts in 1882. He ran for president two years later as the nominee of the Greenback-Labor Party. Like many Gilded Age political figures, he developed a reputation for corruption and sleazy self-enrichment.

Butler sympathized with enslaved Black Southerners who endured terrorist violence when slavery ended. He championed mill workers and campaigned to improve working conditions in the nation’s factories.3 He fought for his beliefs with fiery passion.

Ben Butler on the House floor in 1871 as portrayed in the Wheeling Daily Register.

Ben Butler on the House floor in 1871 as portrayed in the Wheeling Daily Register.Contemporaries seized on this latter characteristic to denigrate and dismiss him. Journalist George Alfred Townsend called Butler a demagogue. “Never in a republic, has one man succeeded in making himself so terrible,” Townsend wrote. “Appealing always to the instinct of fear, he has thus far succeeded beyond the power of talents, of social influence, of wealth, or of popularity, in putting himself at the head of every assault.”4

Somewhat more judiciously, Butler rival James G. Blaine reached the same conclusion.

“He exhibited an extraordinary capacity for agitation, possessing in a high degree what John Randolph described as the ‘talent for turbulence,'” Blaine wrote in 1885. “The stormier the scene, the greater his apparent enjoyment and the more striking the display of his peculiar ability.”5

Distracted by the pyrotechnics, Townsend and the usually astute Blaine failed — like so many others — to discern the underlying philosophical principles that guided Butler during a career that began before the Civil War and continued until his death in 1893.

At its simplest, Butler’s political lodestar was sympathy for the downtrodden born of his hardscrabble beginnings and lifelong antipathy for the bluestocking aristocracy of Massachusetts. “I must always be with the under dog in the fight,” he declared. “I can’t help it. I can’t change, and on the whole I don’t want to.”6

Principle and pugnacity guided Butler throughout his life. Born in 1818 in New Hampshire, Butler faced adversity at a young age. His father died when he was five months old. Butler and his mother moved to Lowell, where she worked as a cleaning woman at a factory dormitory. He briefly attended Exeter Academy but received most of his schooling in Lowell. In both locations, he was remembered as much for his prickly demeanor as his academic prowess.7

He took up the law as a young man and became a successful criminal attorney in Lowell. He earned a commission as a brigadier general of the state militia and became active in Democratic politics. In 1857, Davis, then secretary of war for President James Buchanan, put Butler on West Point’s Board of Visitors. When Democrats gathered in Charleston in 1860 to nominate a presidential candidate, Butler backed Davis in the mistaken belief that he was a moderate on slavery who would be acceptable to fire-eating Southerners and anti-slavery Northerners.8

Ben Butler in uniform. Library of Congress.

Ben Butler in uniform. Library of Congress.The attack on Fort Sumter in April 1861 disabused Butler and countless other Americans of the idea that the emerging sectional conflict over slavery could be settled peaceably. Responding to a call from Secretary of War Simon Cameron for troops to protect Washington, Butler arrived in Maryland and acted vigorously to keep the state from seceding. He threatened legislators with arrest if they voted for secession, seized the state’s Great Seal to prevent legislation from becoming law, and took control of Baltimore to keep local rebel sympathizers from running amok.9

Butler remained in uniform throughout the war, but his record as a commander was undistinguished at best and dismal at worst. Hesitancy and poor decision-making led to defeats at Big Bethel, the James River, and Wilmington, N.C. “As a general in the field, the military critics do not accord him any high standing,” the New York Times wrote.10

But Butler’s reputation was shaped more dramatically by his gradual awakening to the injustice of slavery and his hostility toward secessionists. The politician who had allied himself with Davis before the war became the Union commander who in 1861 refused to return Black men and women to their enslavers when they fled to the Union lines. Butler called them “contraband of war.” Butler’s action, Blaine wrote, “solved a question of policy which otherwise might have been fraught with serious difficulty. In the presence of arms, the Fugitive-slave law became null and void, and the Dred Scott decision was trampled under the iron hoof of war.”11

As the military governor of New Orleans after its capture in April 1862, Butler declared that any female who “by word, gesture, or other movement” insulted Union Army troops would be “treated as a woman of the town, plying her vocation.” The order followed a series of provocative incidents, including the emptying of a chamber pot on Naval Capt. David Farragut, and provoked a storm of international outrage.

“Men of the South, shall our mothers, wives, daughters and sisters be thus outraged by ruffianly soldiers of the North?” Confederate Gen. G.T. Beauregard fulminated. Davis ordered Butler’s execution without trial were he captured. In Britain, Prime Minister Palmerston denounced the order as a blot on the honor of Anglo-Saxon arms. But Butler’s order worked, historian Francis Russell noted. The provocations ceased, and no women were arrested. Nevertheless, the episode made Butler persona non grata throughout the South for the rest of his life.12

Allegations of corruption further marred Butler’s reputation. He was alleged to have smuggled stolen silver spoons out of New Orleans in a coffin while he ran the city. The accusation was untrue, but the story stuck. The unflattering nickname “Spoons” trailed Butler for the rest of his career.13

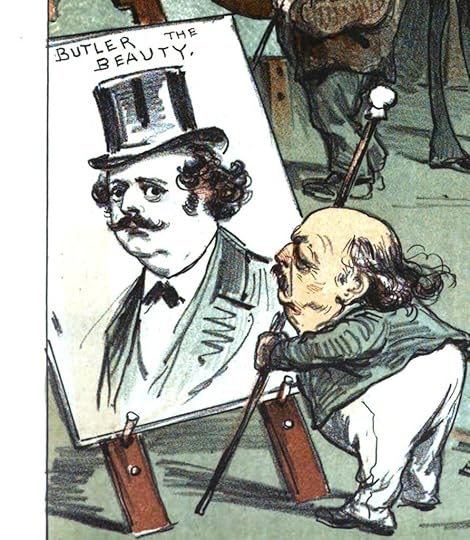

A Puck cartoon from August 1881 shows Ben Butler as he would have liked to be seen.

A Puck cartoon from August 1881 shows Ben Butler as he would have liked to be seen.After the war, all traces of Butler’s antebellum Democratic loyalties vanished. He returned to Massachusetts and was elected to Congress as a Republican in 1866. He quickly emerged as a prominent radical Republican critic of President Andrew Johnson’s lenient approach to Reconstruction and acted as Johnson’s lead prosecutor during his impeachment trial in 1868.

With the fate of Johnson’s presidency on the line, Butler pursued a characteristically aggressive course. He sharply questioned witnesses, raised numerous minuscule evidentiary questions, and insulted Johnson’s lawyers. Butler managed to keep the unwieldy seven-member prosecution team on the attack but “seems to have no power in conciliation,” Townsend wrote in the Chicago Tribune. That shortcoming cost the prosecution the support of key Republicans,14 and helped Johnson escape conviction by one vote.

Moderate and conservative Republicans had additional reasons to scorn the combative Lowell lawmaker. Butler pushed for aggressive federal action to protect the civil and political rights of once-enslaved Black Southerners targeted by Ku Klux Klan and other white terrorists. The legislation backed by Butler would have enabled the federal government to suspend habeus corpus and use federal troops to restore order in Southern states where chaos reigned. Butler blasted the dithering of his colleagues in March 1875 when the House Republican leadership connived with Democrats to permit an all-night filibuster that doomed the bill.

“When they hear the shriek of ‘murder,’ and see the widowed wife and orphaned children coming north, fleeing white-leaguers and Ku-Klux raiders, I trust their sleep will be as sweet as it was on the night I was standing here for the safety of these poor creatures,” he said of his complacent colleagues.15 The bill passed, but too late for the Senate to act. Subsequent violence validated Butler’s warning.

His outspoken opposition to conservative monetary policies further antagonized leading Republicans. After the war, Butler defended the use of paper money to pay off bonds used to finance the war effort. “Why, it is said we must not interfere with the national banks because they patriotically helped us during the war,” he said in 1867. “On the contrary, they helped themselves, not us.”16 While Butler’s support of paper money and hostility to banks reflected the views of a diverse group of Republicans, the position was anathema to party leaders, including Blaine.

On some issues, Butler remained a loyal Republican. He energetically defended fellow Massachusetts Republican Oakes Ames on the House floor when Ames was accused of malfeasance in the Credit Mobilier affair and other members of the party — although sympathetic to Ames — were unwilling to stand up for their colleague. But Butler committed a grievous political blunder when he succeeded in getting Congress to approve a pay raise for itself. Public fury with what became known as the “salary grab” drove scores of Republicans to defeat — including Butler — and allowed Democrats to take control of the House.

Butler returned to Congress in 1876 as a Republican but soon broke with the party for good. He ran twice for governor of Massachusetts as a Democrat and was elected for a single term in 1882. Two years later, he was the Greenback-Labor Party’s candidate for president but performed poorly, even by the standards of a third-party candidate. His days in politics were over. He died in 1893.

A “presidential valentine” for Ben Butler published in Puck, Feb. 13, 1884.

A “presidential valentine” for Ben Butler published in Puck, Feb. 13, 1884.Toward the end of his life, Butler explained that his political career had been guided by the legacy of two Founding Fathers seen as being at opposite ends of the political spectrum.

“I declare my political convictions to be these,” Butler wrote in his autobiography, published in 1892. “As to the powers and duties of the government of the United States, I am a Hamiltonian Federalist. As to the rights and privileges of the citizen, I am a Jeffersonian Democrat.” Every citizen, he believed, possessed the right to “call on either the State, or the United States, or both, to protect them in equality of powers, equality of rights, equality of privileges, and equality of burdens under the law, by carefully and energetically enforced provisions of equal laws justly applicable to every citizen.”17

Butler believed the federal government needed to be strong enough — and active enough — to protect the freedoms and aspirations of American citizens. Liberals of the 20th century made this synthesis of Hamiltonian and Jeffersonian principles their watchword. But in the second half of the 19th century, it was a unique approach to politics — and too much for most Americans.

After his death, the Washington Post took note of Butler’s idiosyncratic career. The newspaper praised “the fervor of his patriotism and the “depth of his sympathies with humanity” while noting his “somewhat rugged and uncouth characteristics.” Butler “was always a striking and forceful personality, for whom the American people had great admiration, and whom but for the peculiar and heterodox drift of his political beliefs (ital added), they would have delighted to honor with the highest honors in their gift.”18

In other words, America wasn’t ready for Ben Butler.

“Sorrow of the Veterans,” Washington Post, Jan. 12, 1893, p. 1. ︎Bruce Catton, Terrible Swift Sword (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday and Co., 1963), p. 359.

︎Bruce Catton, Terrible Swift Sword (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday and Co., 1963), p. 359.  ︎Francis Russell, “Butler the Beast?” American Heritage, April 1968, Vol. 19, Issue 3. Hereafter referred to as Russell.

︎Francis Russell, “Butler the Beast?” American Heritage, April 1968, Vol. 19, Issue 3. Hereafter referred to as Russell.  ︎George Alfred Townsend, Washington Outside and Inside (Hartford, Conn., and Chicago, James Betts & Co., 1874), p. 374.

︎George Alfred Townsend, Washington Outside and Inside (Hartford, Conn., and Chicago, James Betts & Co., 1874), p. 374.  ︎James G. Blaine, Twenty Years of Congress Vol. 2 (Norwich, Conn., The Henry Bill Publishing Co., 1885), p. 289.

︎James G. Blaine, Twenty Years of Congress Vol. 2 (Norwich, Conn., The Henry Bill Publishing Co., 1885), p. 289.  ︎Governor Benj. F. Butler, “Argument Before the Tewksbury Investigation Committee,” Jukly 15, 1883, p. 29.

︎Governor Benj. F. Butler, “Argument Before the Tewksbury Investigation Committee,” Jukly 15, 1883, p. 29.  ︎Russell.

︎Russell.  ︎Ibid.

︎Ibid.  ︎Ibid.

︎Ibid.  ︎“Benjamin F. Butler,” New York Times, Jan. 12, 1893, p. 4.

︎“Benjamin F. Butler,” New York Times, Jan. 12, 1893, p. 4.  ︎James G. Blaine, Twenty Years of Congress Vol. 1 (Norwich, Conn., The Henry Bill Publishing Co., 1884), p. 369.

︎James G. Blaine, Twenty Years of Congress Vol. 1 (Norwich, Conn., The Henry Bill Publishing Co., 1884), p. 369.  ︎Catton, p. 359; James McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988, p. 552; “From Corinth and the South,” Chicago Tribune, May 26, 1862, p. 1; Russell.

︎Catton, p. 359; James McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988, p. 552; “From Corinth and the South,” Chicago Tribune, May 26, 1862, p. 1; Russell.  ︎Russell; William Dana Orcutt, “Ben Butler and the Stolen Spoons: The Documents in the Case, from His Unpublished “Private and Official Correspondence,” North American Review, Vol. 207, No. 746, Jan. 1918, pp. 66-80.

︎Russell; William Dana Orcutt, “Ben Butler and the Stolen Spoons: The Documents in the Case, from His Unpublished “Private and Official Correspondence,” North American Review, Vol. 207, No. 746, Jan. 1918, pp. 66-80.  ︎“Scenes at the Capitol During Impeachment,” Chicago Tribune, May 9, 1868, p. 2; David O. Stewart, Impeached: The Trial of Andrew Johnson and the fight for Lincoln’s Legacy (New York, London, Toronto, Sydney: Simon & Schuster, 2009, pp.170-171.

︎“Scenes at the Capitol During Impeachment,” Chicago Tribune, May 9, 1868, p. 2; David O. Stewart, Impeached: The Trial of Andrew Johnson and the fight for Lincoln’s Legacy (New York, London, Toronto, Sydney: Simon & Schuster, 2009, pp.170-171.  ︎U.S. Congress, House, Congressional Record, 43rd Congress, 1st session, Feb. 27, 1875, p. 1,906.

︎U.S. Congress, House, Congressional Record, 43rd Congress, 1st session, Feb. 27, 1875, p. 1,906.  ︎Butler’s congressional statement quoted in Benjamin F. Butler, Butler’s Book: A Review of His Legal and Political Career (Boston: A.M. Thayer & Co., 1892), p. 944.

︎Butler’s congressional statement quoted in Benjamin F. Butler, Butler’s Book: A Review of His Legal and Political Career (Boston: A.M. Thayer & Co., 1892), p. 944.  ︎Ibid., p. 86.

︎Ibid., p. 86.  ︎“The Late Gen. Butler,” The Washington Post, Jan. 12, 1893, p. 4.

︎“The Late Gen. Butler,” The Washington Post, Jan. 12, 1893, p. 4.  ︎

︎

March 24, 2025

“A new orbit:” How James B. Weaver launched his partisan odyssey

First in a series that looks at some of the prominent figures of the hyper-partisan Gilded Age who switched parties — often more than once and in one case with tragic consequences.

At the end of a political career in which he switched parties several times, ran twice for president, served three terms in Congress, and allied himself with William Jennings Bryan, Iowa populist James B. Weaver looked back on the years when everything began to change.1

Born in 1833 in Ohio, Weaver moved with his family across the Midwest, to Michigan and ultimately to Iowa, where his father took a stab at farming before moving to Bloomfield, the county seat of Davis County.

Abram Weaver brought his loyalty to the Democratic Party with him as he and his family migrated west and passed it on to his son. In what he remembered as his political debut, Weaver recalled besting future Republican congressman and secretary of war George McCrary in a debate about the Kansas-Nebraska Act.

But the younger Weaver’s political outlook altered dramatically by the end of the decade. After a stint at law school in Cincinnati studying under Whig jurist Bellamy Storer, Weaver shifted his loyalties to the new Republican Party. Those were the years of the Lecompton Constitution and “Bleeding Kansas,” the Dred Scott decision and the brutal caning of Senator Charles Sumner on the Senate floor by South Carolina Democrat Preston “Bully” Brooks.

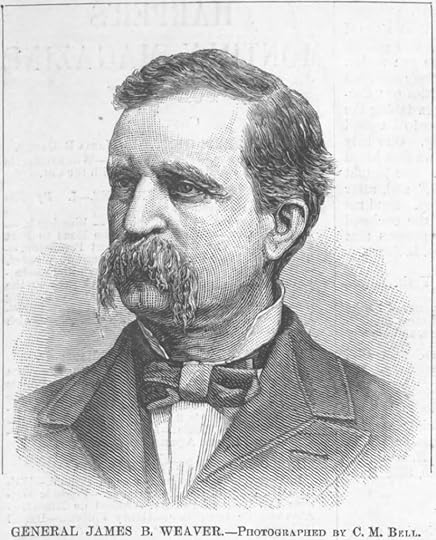

James B. Weaver in 1880. Harper’s Weekly.

James B. Weaver in 1880. Harper’s Weekly.Reminiscing about this tumultuous period in an unpublished biographical memorandum written toward the end of his life, Weaver recalled that the “world was changing and searching out a new orbit.”

Over the next several weeks, I’ll be writing about figures like Weaver whose partisan and ideological affiliations veered in new directions in response to the wrenching changes wrought by civil war and industrialization. Some settled into stable partisan orbits; others careened from one party to another. In addition to Weaver, I’ll be writing about:

Benjamin Butler of Massachusetts, who evolved from a Democrat who supported Jefferson Davis for the party’s 1860 presidential nomination into a radical Republican who favored vigorous federal enforcement of civil and voting rights legislation in the South before leaving the party over monetary questions.John Logan of Illinois, like Butler a Democrat at the start of the war who embraced the Union cause. Logan served as a Union general during the war and became a staunch Republican. Once he switched parties he stayed put and became a party power broker.Albert Parsons experienced the most dramatic political evolution and suffered the most extreme consequences. The Texas-born anarchist served in the Confederate army and joined the Republican Party after the war before he moved to Chicago to become a radical supporter of labor. Parsons was hanged in 1887 after being convicted of complicity in the death of a Chicago police officer during the Haymarket Riot of 1886.For Butler, Logan and Parsons, it was the Civil War and its aftermath that launched them in new political directions. Weaver’s search for a “new orbit” began as the partisan divisions of the antebellum era broke down and a new party emerged in its place.

Like Abram Weaver, Iowa’s partisan loyalties in the 1850s were firmly Democratic. At the beginning of the decade, two Democrats — Augustus Caesar Dodge and George Wallace Jones — represented Iowa in the Senate. Democratic presidential candidates Lewis Cass, Franklin Pierce and James Buchanan carried the state in 1848,1852 and 1856.

While the young Weaver left for Cincinnati with his father’s Democratic allegiance, he returned with a new perspective. Cincinnati was a hotbed of agitation over slavery. Storer aligned with abolitionists and urged his students to apply the precepts of the Bible to their legal careers. Weaver came home fired by anti-slavery idealism.

The Iowa to which he returned was undergoing profound political change. The Kansas-Nebraska Act, which raised the ominous prospect of slavery being permitted in western territories, roiled the state. As the Whig Party withered and died, anti-slavery Democrats joined with like-minded former Whigs and abolitionists to rally around a new political entity, the Republican Party.

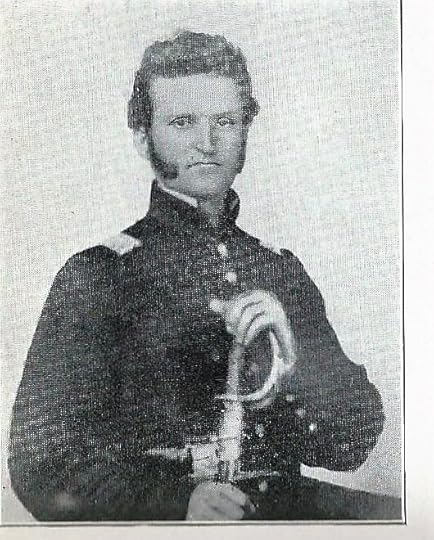

A young James B. Weaver in the uniform of the Union Army.

A young James B. Weaver in the uniform of the Union Army.The Supreme Court’s infamous Dred Scott ruling that Black Americans lacked standing as citizens further inflamed public opinion in Iowa. In an address to state legislators in 1858, Iowa Gov. James B. Grimes expressed the hope that “you will explicitly declare that you will never consent that this state shall become an integral part of a great slave republic, by assenting to the abhorrent doctrines of the Dred Scott decision, let the consequences of dissent be what they may.”2

Weaver leaped enthusiastically into the ranks of anti-slavery Republicans and spoke across southern Iowa in favor of the new party. According to the late William Safire, he added to the American political lexicon when he denounced the brutal assault of an Iowa evangelist who incurred the wrath of white Texans for preaching to enslaved Black men and women. The preacher returned to Iowa with the blood-soaked garment he was wearing when he was whipped. “Under this bloody shirt we propose to march to victory,” Weaver declared.3

In 1860, Weaver joined the Iowa delegation in Chicago where Republicans nominated Abraham Lincoln for president and campaigned for him back in Iowa. At a rally close to the border with slave-state Missouri, Weaver and an associate rose to speak for Lincoln when a fight broke out. Order was restored after another person at the meeting threatened to “mash the head of the first man who tried to disturb the meeting.” Weaver and his comrade made their case for Lincoln and left for friendlier environs. Lincoln carried Iowa to inaugurate a long period of Republican dominance in the state.

A Lincoln-Hamlin poster from 1860. Library of Congress.

A Lincoln-Hamlin poster from 1860. Library of Congress.After Southern rebels fired on Fort Sumter in 1861, Weaver joined an Iowa infantry regiment and fought at Fort Donelson and Shiloh. He was promoted to colonel in the field, received a brevet appointment as brigadier general after returning home, and was elected as a district attorney. His political prospects seemed bright. But then things started to go wrong.

Weaver was an ardent supporter of prohibition, but Republican elders — with an eye on German and Irish voters in the state — resisted identifying too closely with temperance and deemed Weaver too extreme on the issue. In 1874, he lost the Republican nomination to Congress at a district convention. A year later, he was the favorite to win the party’s nomination for governor but lost when a last-minute convention stampede turned to Samuel Kirkwood. He was “supposed to be the coming man,” an Iowa newspaper observed. In 1875 it appeared his political career had hit a dead end.

Instead of trimming his sails on temperance to win the support of the Republican establishment, Weaver turned to another party to crusade on another issue. Following the Panic of 1873 and the ensuing depression, Americans divided sharply on monetary policy questions. Conservatives in both parties favored deflationary “hard money” policies linking the dollar to the gold standard, while others demanded “soft money” paper currency whose inflationary qualities won the support among debt-laden farmers.

Weaver enlisted in the Greenback-Labor Party as it seemed poised to emerge as Republicans as a party of reform just as Republicans had 20 years earlier. The new party embraced a broad agenda that focused primarily on soft money but also included calls for banning child labor and the regulation of working conditions. It condemned “as most dangerous the efforts everywhere manifest to restrict the right of suffrage” and demanded an income tax.

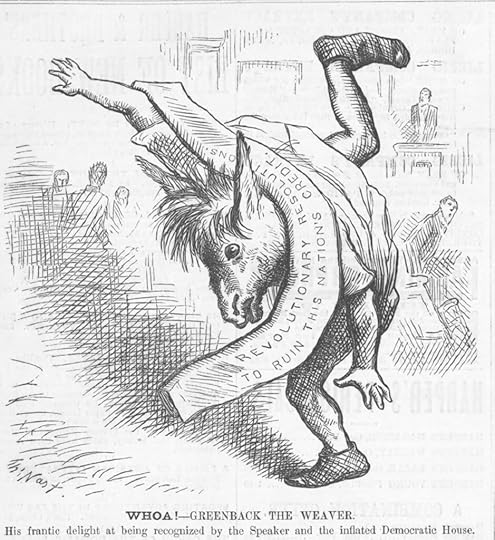

Harper’s Weekly cartoonist Thomas Nast didn’t think much of Weaver and portrayed him as the donkey Nick Bottom from Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dre

am.

Harper’s Weekly cartoonist Thomas Nast didn’t think much of Weaver and portrayed him as the donkey Nick Bottom from Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dre

am.

Iowans elected Weaver to Congress in 1878 and he quickly emerged as the party’s leading spokesman. In the House, he campaigned tirelessly to elevate currency issues and succeeded, with the help of Republican leader James A. Garfield, in forcing a debate on Greenback currency resolutions designed to put Democrats on the hot seat. In July 1880, the third party nominated Weaver for president.

If Weaver hoped the Greenbacks would replicate the success of Republicans, he was sorely mistaken. Plagued by internal dissent and dominated by a collection of visionaries and cranks, the party performed poorly in the presidential election in which Republican candidate James A. Garfield narrowly defeated Democrat Winfield Scott Hancock. The third party never recovered and faded from view before the decade was out. Weaver returned to Congress with the help of Democrats in 1884 and was reelected to a second term, but the reform movement stalled and he was defeated in 1888.

Weaver cast about for another cause. He joined Sooners who emigrated to the Oklahoma Territory but failed to establish himself as their leader. He returned to Iowa and edited a weekly newspaper that championed the cause of the embattled farmer. Meanwhile, a new movement of Agrarian radicals who emerged on the Texas plains and would soon sweep through the agricultural regions of the Midwest, Far West and South. As the movement evolved into a political party it embraced the name Populist.

Weaver gravitated to the Populists, who amplified the soft money position of the Greenback-Labor Party, echoed Greenback support of a graduated income tax, and called for government ownership of the railroads. He wrote a book outlining the Populist critique of the economy and American politics. Weaver mounted a second campaign for the White House as the Populist presidential candidate in 1892 and carried four states — the first third-party candidate to do so since 1860.

Four years later, though, Weaver decided to convince his party to endorse the Democratic presidential nominee, William Jennings Bryan. Weaver regarded Bryan as a powerful spokesman for the issues Populists cared about and believed that advancing the cause was more important than perpetuating the third party. The Populists nominated Bryan as their candidate but thereafter withered into obscurity. Weaver eventually followed Bryan into the Democratic Party.

James B. Weaver (left) and William Jennings Bryan in 1896 as seen on the cover of Puck. Library of Congress.

James B. Weaver (left) and William Jennings Bryan in 1896 as seen on the cover of Puck. Library of Congress.For many politicians in the 19th century, the Civil War proved to be the decisive factor in determining their partisan allegiances. While many who left the Democratic Party to become Republicans stayed with the party of Lincoln, Weaver pursued opportunities for political and economic reform whenever they appeared. His formative political experience came in the tumultuous years before the Civil War, when the Whig Party died and the Republicans — attracting anti-slavery Democrats, Whigs and radical abolitionists — emerged as a new force in American politics. Weaver was a Democrat in his youth, a Republican as a young man, and a Greenback and Populist in middle age before finally returning to the Democratic Party in his final years. His search for a “new orbit” began as Americans lurched toward civil war and continued into the 20th century.

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

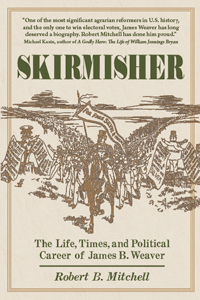

Skirmisher: The Life, Times, and Political Career of James B. Weaver, won the Benjamin F. Shambaugh Award from the State Historical Society of Iowa in 2009 as “the most significant book on Iowa history published in the previous year.” It is available at amazon.com. My latest book, The Partisans: James G. Blaine, Roscoe Conkling, and the Politics of Rivalry and Revenge in the Gilded Age, is coming soon from Edinborough Press.

Skirmisher: The Life, Times, and Political Career of James B. Weaver.

Skirmisher: The Life, Times, and Political Career of James B. Weaver. Congress and the King of Frauds: Corruption and the Credit Mobilier Scandal at the Dawn of the Gilded Age

Congress and the King of Frauds: Corruption and the Credit Mobilier Scandal at the Dawn of the Gilded Age Coming soon: The Partisans: James G. Blaine, Roscoe Conkling, and the Politics of Rivalry and Revenge in the Gilded AgeUnless otherwise noted, this account of Weaver’s experiences in the 1850s is based on my biography: Skirmisher: The Life, Times, and Political Career of James B. Weaver (Edinborough Press).

Coming soon: The Partisans: James G. Blaine, Roscoe Conkling, and the Politics of Rivalry and Revenge in the Gilded AgeUnless otherwise noted, this account of Weaver’s experiences in the 1850s is based on my biography: Skirmisher: The Life, Times, and Political Career of James B. Weaver (Edinborough Press).  ︎Journal of the House of Representatives of the Seventh General Assembly of the State of Iowa (Des Moines, J. Teesdale, State Printer, 1858), p. 29.

︎Journal of the House of Representatives of the Seventh General Assembly of the State of Iowa (Des Moines, J. Teesdale, State Printer, 1858), p. 29.  ︎William Safire, Safire’s Political Dictionary (Oxford University Press, 2008), p. 62.

︎William Safire, Safire’s Political Dictionary (Oxford University Press, 2008), p. 62.  ︎

︎

February 21, 2025

“The King of Frauds” and investigative journalism

I want to thank University of Maryland Professor Mark Feldstein for inviting me to speak to his investigative journalism seminar at the Merrill School of Journalism earlier this week about the story that broke open the Credit Mobilier scandal. It was an honor and pleasure to speak to idealistic aspiring journalists and a chance to reflect on an early example of investigative reporting.

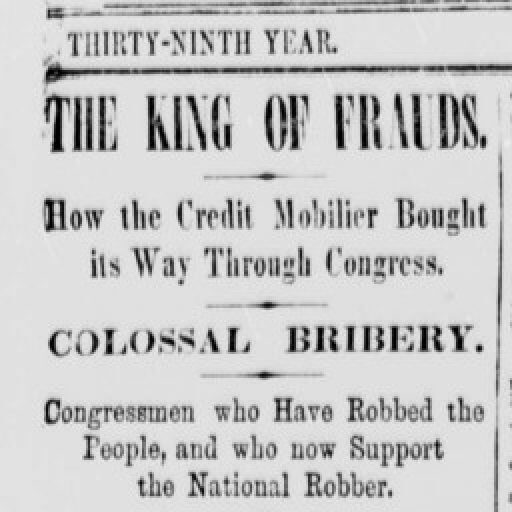

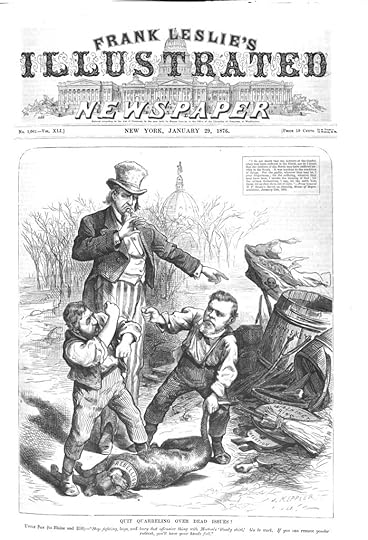

The story of the Credit Mobilier scandal begins on September 4, 1872, when the four-page New York Sun filled its entire front page, and several columns on two inside pages, with a blockbuster exclusive that dominated the headlines for months and reverberated politically for years. Under the headline “The King of Frauds,” the feisty New York daily detailed the operations of Credit Mobilier of America, the lucrative construction arm of the transcontinental Union Pacific railroad, and how its investors sought influence in Congress.

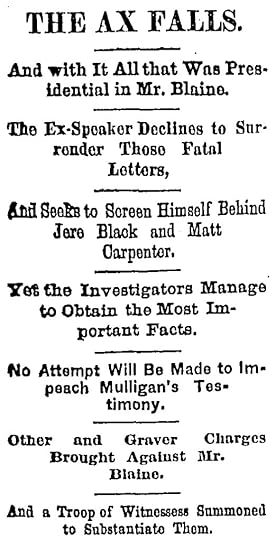

The headlines atop the Sept. 4, 1872 story in the New York Sun that broke the Credit Mobilier scandal wide open.

The headlines atop the Sept. 4, 1872 story in the New York Sun that broke the Credit Mobilier scandal wide open.The scoop, unearthed by Sun Washington correspondent Albert M. Gibson, opened with inflammatory headlines that promised revelations of “colossal bribery” and “congressmen who have robbed the people, and who now support the national robber.” Several introductory paragraphs followed in a similar vein. The story promised to reveal “the most damaging exhibition of official and private villainy and corruption ever laid bare to the gaze of the world.”

Although the scoop appeared without a byline, Gibson lapsed into the first person to describe his disgust with what he discovered. “If there was room for a doubt in this case, I for one would be in favor of giving these men the benefit of it, for it is almost beyond belief that our public men could have fallen so low. But there is no escaping the conclusion that they are guilty.”1

Those were different times.

The rest of the story consisted of transcribed deposition testimony from a lawsuit filed against Credit Mobilier by railroad speculator Henry Simpson McComb. Its most explosive revelation was the publication of letters written by Representative Oakes Ames of Massachusetts, one of the Union Pacific’s biggest stockholders and a Credit Mobilier investor.

The letters were written to McComb, who had been pestering Ames for additional Credit Mobilier shares after the company divided unissued stock among its leading investors, many of whom also held stock in the Union Pacific. Ames declined to provide McComb with any of the extra Credit Mobilier shares and explained why.

The unclaimed stock had been distributed on Capitol Hill, according to Ames, with the intent with creating a congressional cadre motivated to support the Union Pacific’s interests on Capitol Hill.

“We want more friends in this Congress,” Ames wrote in one of his letters to McComb, “& if a man will look into the law (& it is difficult to get them to do so unless they have an interest to do so), he cannot help being convinced that we should not be interfered with.”2

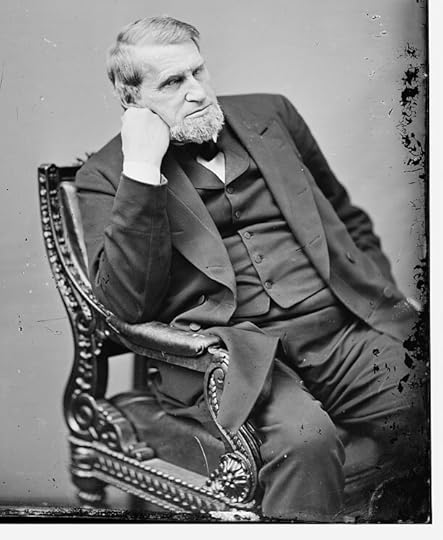

Rep. Oakes Ames, R-Mass. Library of Congress.

Rep. Oakes Ames, R-Mass. Library of Congress.In a subhead at the top of the story, the Sun printed a list of members of Congress alleged to have received Credit Mobilier shares from Ames. The list included:

— Vice President Schuyler Colfax, who bought shares while House Speaker;

— James G. Blaine, who succeeded Colfax as Speaker;

— Senator Henry Wilson of Massachusetts, who would succeed Colfax as Grant’s vice president;

— James A. Garfield, a rising Republican star in the House who would be elected president in 1880; and

— Democrat James Brooks of New York, the sole member of his party implicated in the scandal.

Modern journalists would find the story extremely odd. The headlines were comically sensational. The Sun made no attempt to reach any of the congressmen named for comment. Paragraph after paragraph described in excruciating detail the financial machinations of Credit Mobilier and the Union Pacific. The story’s most explosive material – the letters written by Ames – appeared at the very end.

In addition, there was much that was wrong with the Sun’s expose. Many of the lawmakers it listed – including Blaine — did not obtain Credit Mobilier shares. The paper charged that members received between 2,000 and 3,000 shares apiece when in fact most received 30 and only one – Brooks – received as many as 150.

Mistakes such as these enabled partisan Republican newspapers to dismiss the story out of hand. The New York Times characterized it as a “stupid falsehood” published by a despicable scandal sheet. “The charge originally appeared in the Sun,” the Times sniffed, “which is prima facie evidence that it is a lie.” The New York Tribune, whose editor Horace Greeley was running a quixotic long-shot campaign for president against Ulysses S. Grant, reluctantly printed a condensed version of the story on an inside page. Even so, the Tribune was closer to the mark than the Times when it predicted that the “public will look with deep interest at further developments in the case.”3

Henry Simpson McComb. Library of Congress.

Henry Simpson McComb. Library of Congress.The Tribune proved correct. The story would not die. It tapped into growing animosity directed at the railroad industry, whose corrupt influences in state legislatures and abusive pricing practices enraged government reformers and farmers from Maine to California. At the same time, the story confirmed what members of Congress and some in the press already knew or suspected about the extent of Credit Mobilier’s influence in Congress.

In March 1868, more than four years before the Sun published its story, Republican Representative Cadwallader C. Washburn of Wisconsin delivered a long speech on the House floor in which he flayed Credit Mobilier as a cabal of investors who were fleecing the Union Pacific by overcharging for construction work.

Four months later, the managing editor of the New York Tribune alerted Republican Representative Elihu Washburne of Illinois (Cadwallader’s brother) about sensational evidence regarding Credit Mobilier and members of Congress that had emerged in a New York courtroom. John R. Young advised Washburne that the allegations would “astonish,” but added he would sit on the story because it threatened to hurt Republican prospects in the upcoming election.

Others were less hesitant to speak out. Writing in the North American Review about railroad finance in 1869, Charles Francis Adams called Credit Mobilier a threat to democracy itself, “a source of corruption in the politics of the land, and a resistless power in its legislature.”4

The Sun disclosed to the public what had been, in essence, an open secret on Capitol Hill and in some newsrooms. Once it did so, the story caught fire as newspapers reprinted versions of the Sun story and followed up with editorial commentary and stories of their own.

Before the dust settled, three congressional committees investigated Credit Mobilier’s influence on Capitol Hill. The House censured Ames and Brooks, the New York Democrat. A Senate committee recommended the expulsion of Sen. James Patterson of New Hampshire. The scandal permanently tarnished the reputation of Colfax, whose denials of involvement became increasingly improbable as the congressional investigation continued. The scandal shadowed others who were implicated – particularly Garfield – for the remainder of their careers.

Few newspaper exposes have been as consequential.

Advances in printing technology, transportation and communication – most notably the telegraph – allowed newspapers to sell more copies across wider areas and gather news from around the world. News became a commodity demanded by the public that could attract advertisers. The changing business fundamentals of the industry permitted editors and publishers to act independently of parties, although they continued to engage vigorously in the political contests of the day.

Rep. James Brooks, D-N.Y. Library of Congress.

Rep. James Brooks, D-N.Y. Library of Congress.By the 1870s, according to historian Mark Wahlgren Summers, approximately 500 newspapers from Portland, Maine, to San Francisco, published daily editions. By the end of the decade, that number almost doubled.5 As newspapers evolved into publications that provided information rather than just partisan opinion, they retained the services of men – and a few women – who could report on the events of the day.

This evolution would have significant consequences for the way in which Washington was covered. Between 1860 and 1880, the size of the congressional press gallery tripled.6 Correspondents filed daily stories, weekly “letters from Washington” that mixed news and commentary, and prowled the backrooms of Capitol Hill and government departments looking for inside information on legislation and government policy.

When they witnessed important news or uncovered something interesting, however, the correspondents were as likely to exploit that knowledge for personal gain as share it with the public.

Uriah Hunt Painter dabbled in real estate and lobbied for railroads in addition to writing for the Sun and the Philadelphia Inquirer. As a young reporter, he scooped the nation with the first report of the Union defeat at Bull Run in 1861. Before filing his story, however, he tipped off financier Jay Cooke to the Union defeat, allowing Cooke to sell off stock before share prices plummeted on the news. In the years that followed, according to Donald R. Ritchie, Cooke paid Painter to keep him apprised of legislative developments.7

Painter, rather than Gibson, could have been the reporter who broke the Credit Mobilier story after learning about the share sales in the winter of 1867-1868. Rather than expose them to the public, however, he demanded that Ames let him in on the sales. He ended up buying 30 shares, according to Ames, and was “very indignant that he did not get 50 shares.”8

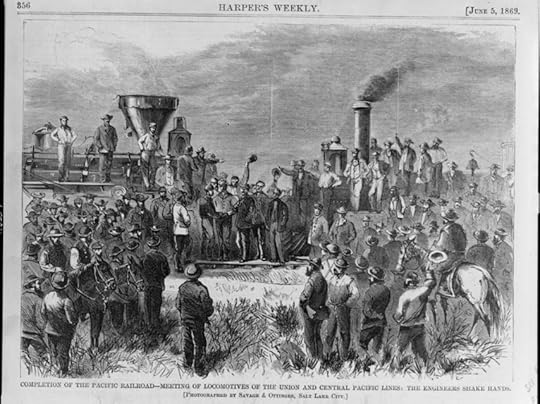

An illustration from Harper’s Weekly shows the joining of the Union Pacific and Central Pacific in Utah that completed the transcontinental railroad in 1869. Library of Congress.

An illustration from Harper’s Weekly shows the joining of the Union Pacific and Central Pacific in Utah that completed the transcontinental railroad in 1869. Library of Congress.When William B. Shaw, a correspondent for the Boston Transcript, found out that the Treasury Secretary planned to hold back payments on Union Pacific bonds, he kept that information from his paper and its readers until he could sell off his bonds. He later bragged to a congressional committee that he routinely put his private interests ahead of the public interest. “I always do these things,” he told lawmakers, “before I let anyone else know.”9

The ethical pillars that guide modern news organizations and their reporters had yet to rise. During this era, newspapers printed sensational “hoaxes” designed to boost circulation or drum up support for an editorial position. They increasingly operated independently of political parties, but their news columns routinely cheered candidates they supported and excoriated their opponents.

How did Gibson get his exclusive? That’s almost as interesting as the scoop itself. An intriguing clue appeared amid the grey front-page columns of the Sun in 1873. The newspaper attributed its scoop to “one of General Garfield’s stories, which he told three and a half years ago, concerning his transactions and the Credit Mobilier.”10

Perhaps it was the memory of this conversation that alerted Gibson to the significance of something he saw during the summer of 1872. Gibson was visiting his friend Chauncey Black at the southern Pennsylvania home of Black’s father, attorney, Democratic elder statesman and wirepuller Jeremiah Black.

While he was there, Gibson noticed that McComb arrived to consult with the elder Black. An unbylined story that appeared in the New York Times in 1885 that was clearly written by Gibson recounts how the correspondent immediately grasped that the visit had something to do with McComb’s lawsuit against Credit Mobilier. To his friend, Gibson “incidentally remarked that the case involved an ugly scandal, and that a number of distinguished public men were compromised by it.”

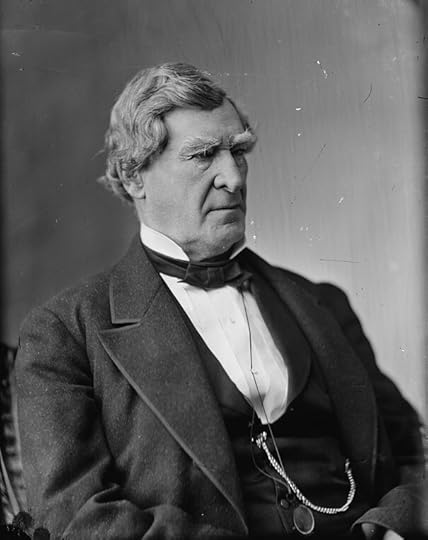

Jeremiah Black. Library of Congress.

Jeremiah Black. Library of Congress.Gibson’s unbylined account says he knew court documents were public records and that he simply needed to go to Philadelphia to get the story. His memoir also includes a fulsome denial that Jeremiah Black would do anything so despicable as leak a story to a reporter. “He was the most punctilious of men when his professional honor was involved,” Gibson asserted. “He would have suffered his right arm to be cut off before he would even indirectly have been a party to the betrayal of the most unimportant secret of one of his clients.”11

In fact, considerable evidence points to Black as Gibson’s source and enabler. After the Sun published, the Chicago Tribune sent renowned correspondent George Alfred Townsend to Philadelphia to discover how the story found its way into print. Townsend tracked down an attorney who worked for Black who possessed the deposition transcript and admitted that “a man came to see me with a letter from Judge Black” that permitted a review of the relevant documents.12

Despite its flaws, in many ways Gibson’s exclusive foreshadows the practices of modern investigative journalism. It relied not on speeches or quotes from sources but on hard documentary evidence. It needed a reporter who put two-and-two together to chase it down. It required digging (and some help from an interested party) to get the needed information.

If the challenges are similar, so are the satisfactions. Gibson put it best as he recalled the moment he discovered pay dirt as he dug through the Credit Mobilier deposition. “To say that I was startled at my find,” Gibson wrote, “would inadequately express my mental state.”13

More than 150 years later, reporters know that feeling well. The hunt for information and the thrill of discovery are timeless characteristics of investigative reporting.

___

I am the author of the forthcoming The Partisans: James G. Blaine, Roscoe Conkling, and the Politics of Rivalry and Revenge in the Gilded Age (Edinborough Press).

Congress and the King of Frauds, my account of the Credit Mobilier scandal, is available at amazon.com.

New York Sun, Sept. 4, 1872, p. 1. ︎Report of the Select Committee to investigate the Alleged Credit Mobilier Bribery, Made to the House of Representatives, February 18, 1873 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1873), p. 7. Hereafter referred to as Report.

︎Report of the Select Committee to investigate the Alleged Credit Mobilier Bribery, Made to the House of Representatives, February 18, 1873 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1873), p. 7. Hereafter referred to as Report.  ︎New York Times, Sept. 7, 1872, p. 6; New York Times, Sept. 14, 1872, p. 4.

︎New York Times, Sept. 7, 1872, p. 6; New York Times, Sept. 14, 1872, p. 4.  ︎Robert B. Mitchell, Congress and the King of Frauds: Corruption and the Credit Mobilier Scandal at the Dawn of the Gilded Age (Roseville, Minn., Edinborough Press, 2018), pp. 31, 33, 44. Hereafter referred to as King of Frauds.

︎Robert B. Mitchell, Congress and the King of Frauds: Corruption and the Credit Mobilier Scandal at the Dawn of the Gilded Age (Roseville, Minn., Edinborough Press, 2018), pp. 31, 33, 44. Hereafter referred to as King of Frauds.  ︎Mark Wahlgren Summers, The Press Gang: Newspapers & Politics 1865-1878 (Chapel Hill and London, University of North Carolina Press, p. 10.

︎Mark Wahlgren Summers, The Press Gang: Newspapers & Politics 1865-1878 (Chapel Hill and London, University of North Carolina Press, p. 10.  ︎Ibid., pp. 81-82.

︎Ibid., pp. 81-82.  ︎Donald R. Ritchie, Press Gallery: Congress and the Washington Correspondents (Cambridge, Mass., and London, Harvard University Press, 1991) p. 98.

︎Donald R. Ritchie, Press Gallery: Congress and the Washington Correspondents (Cambridge, Mass., and London, Harvard University Press, 1991) p. 98.  ︎Report, p. 31.

︎Report, p. 31.  ︎King of Frauds, p. 46-47.

︎King of Frauds, p. 46-47.  ︎New York Sun, Jan. 24, 1873, p. 1.

︎New York Sun, Jan. 24, 1873, p. 1.  ︎New York Times, Feb. 2, 1885, p. 2. Hereafter referred to as Gibson.

︎New York Times, Feb. 2, 1885, p. 2. Hereafter referred to as Gibson.  ︎George Alfred Townsend, Washington Outside and Inside (Hartford, Conn., and Chicago, James Betts & Co., 1874, p. 410).

︎George Alfred Townsend, Washington Outside and Inside (Hartford, Conn., and Chicago, James Betts & Co., 1874, p. 410).  ︎Gibson.

︎Gibson.  ︎

︎

February 14, 2025

“Wherever concealment is desirable, avoidance is advisable”

In the aftermath of his Andersonville speech, James G. Blaine suffered a blow to his reputation from which he never recovered.

The second of two parts

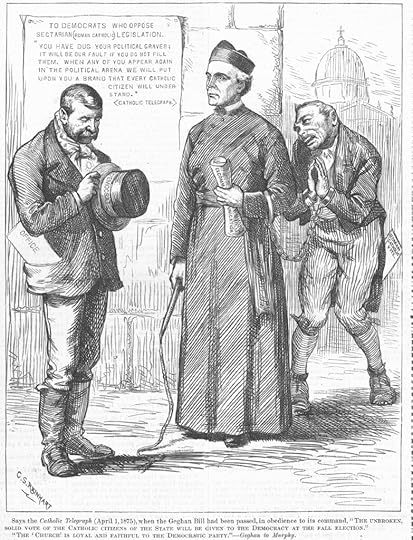

A cartoon from

Puck

published May 21, 1884, shows James G. Blaine as the pied piper of Hamelin with a tattoo reading “Mulligan letters” on his left leg. The cartoon illustrates how the correspondence haunted him eight years after it was revealed.

A cartoon from

Puck