A New Orbit: John A. Logan, a Republican “developed by the war”

The war to save the Union supercharged John A. Logan’s evolution from Douglas Democrat to Radical Republican. Third in a series about Gilded Age party switchers.

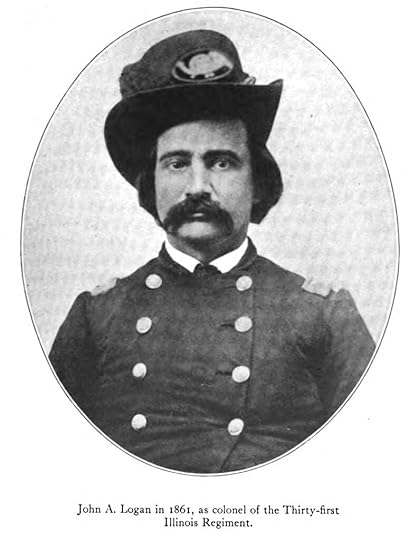

Photo and caption from Mary Logan’s Reminiscences of a Soldier’s Wife.

Photo and caption from Mary Logan’s Reminiscences of a Soldier’s Wife.One of the most dramatic political transformations of the Gilded Age involved an obscure Democratic member of Congress who championed the Fugitive Slave Act and denounced Abolitionists before becoming one of the leading members of the Republican Party.

John Alexander Logan of Illinois was a black-haired attorney elected to Congress in 1858 to represent Illinois’s southernmost congressional district, where Southern sympathies and antipathy toward enslaved Black people ran high. On Capitol Hill and back home, “Black Jack” Logan established himself as a disciple of Senator Stephen A. Douglas, an apostle of the Fugitive Slave Act, and a virulent critic of the Republican Party. By the time of his death in 1886, Logan ranked among the nation’s most prominent Republicans.

A variety of motives drove the party-switchers of the Gilded Age as they searched for what Iowa populist James B. Weaver called a “new orbit.” Becoming politically active in the 1850s, when anti-slavery Democrats joined like-minded Whigs to form the Republican Party, Weaver anticipated and worked for a similar realignment of reform-minded politicians in the decades after the Civil War. He returned to the Democratic Party in the early 20th century when he concluded that William Jennings Bryan offered the best hope for leading a reform movement to power.

Benjamin Butler of Massachusetts left the Democratic Party and embraced the agenda of radical Republicans. As the 1870s continued, Butler broke irrevocably with Republicans over monetary policies that he believed favored the interests of bankers and Wall Street over average citizens. He made a brief return to the Democratic Party before running for president in 1884 at the head of the Greenback ticket. Late in life, Butler described himself as a believer in Hamiltonian means — that is, the vigorous use of federal power — to pursue the Jeffersonian ends of protecting the rights and interests of average citizens.

Logan’s evolution from loyal Democrat to radical Republican began in response to changing political realities and was supercharged by battle. “Logan was developed by the war,” the Chicago Tribune wrote at his death in 1886. “The cavalry bugler sounded the keynote of his character, and in an atmosphere of dust and powder he grew great.”1

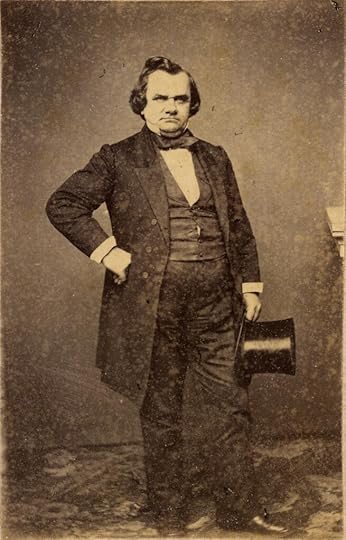

Senator Stephen A. Douglas. Library of Congress.

Senator Stephen A. Douglas. Library of Congress.Few observers would have predicted greatness for Logan before the war, when his shrill defenses of the Fugitive Slave Act and partisan denunciations of Lincoln earned him notoriety in the Northern press.

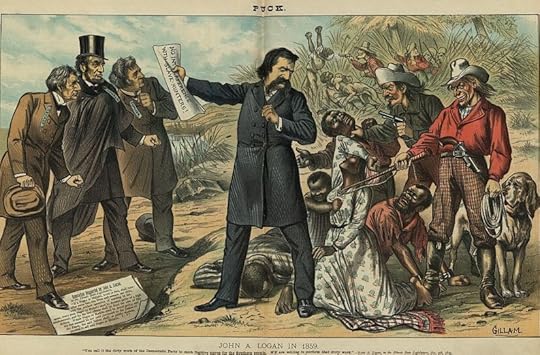

“Every fugitive that has been arrested in Illinois, or in any of the western states — and I call Illinois a western state because I am ashamed longer to call it a northern state — has been made by Democrats,” Logan told the House on Dec. 9, 1859.

He disparaged “Abolitionist hordes” in the northern part of the state who made it impossible to enforce the infamous Fugitive Slave Act that treated escapees from bondage as the missing property of enslavers. “In Illinois Democrats have all that work to do. You call it the dirty work of the Democratic Party to catch fugitive slaves for southern people. We are willing to perform that dirty work. I do not consider it disgraceful to perform any work, dirty or not dirty, which is in accordance with the laws of the land and the Constitution of the country, and calculated to assist men in recovering that which is their right, guaranteed to them under the Constitution and the laws of the land.”2

The Chicago Tribune and other Republican newspapers promptly dubbed the Southern Illinois Democrat “Dirty Work Logan.”3

Two years later, after Logan characterized Abraham Lincoln as a “strictly sectional candidate” whose election would trigger the conflict feared by all, a friendly constituent chastised him in a letter published by the Illinois Journal in Springfield. Abandon the partisan rhetoric giving aid and comfort to Southern fire-eaters, the letter urged Logan, and rise to the defense of your country.

Puck dramatizes Logan’s infamous promise in 1859 that Democrats were willing to do to the “dirty work” of capturing Black escapees from enslavement.

Puck dramatizes Logan’s infamous promise in 1859 that Democrats were willing to do to the “dirty work” of capturing Black escapees from enslavement.“You are a young man,” Logan was advised. “If you will, you have a fine career opening up before you; and now, with your position, in this crisis, you have a golden opportunity to make your mark, and take your stand among the true patriots and statesmen of our country’s history, which, once let slip, will never recur again.”4

It was good advice, but Logan wasn’t ready to act on it. In Chicago on May 20, Douglas thundered that “there are no neutrals in this war, only patriots and traitors.” Struggling to remain impartial regarding the looming sectional conflict, Logan reacted with fury to the analysis of his ally and mentor. Meanwhile, unfavorable newspaper coverage and growing pro-Union sentiment in his district Logan’s position increasingly untenable.5

The New York Herald reported from Cairo, Ill., on June 12 that Logan — along with members of his family — was plotting to “separate Southern Illinois from the remainder of the state” to support the Confederacy. The story was false, but it was followed by critical commentary closer to home. Less than a week later, the Daily Illinois State Journal in Springfield noted that pro-Union “Egyptian Home Guard” called for Logan’s resignation from Congress. “There seems to be,” the newspaper observed, “a general uncertainty as to the exact ‘sentiments’ of Mr. Logan.”6

Logan needed to get on the right side of rapidly hardening pro-Union sentiment in Illinois. He soon got his chance.

On June 19, Grant bumped into Logan and another Democratic congressman from Illinois, John McClernand, in Illinois’s capital city. The encounter coincided with a critical moment in the mobilization for war. Short-term enlistments in the state militia were expiring, and the troops Grant was training were being asked to sign up for three years of service in the U.S. Army.

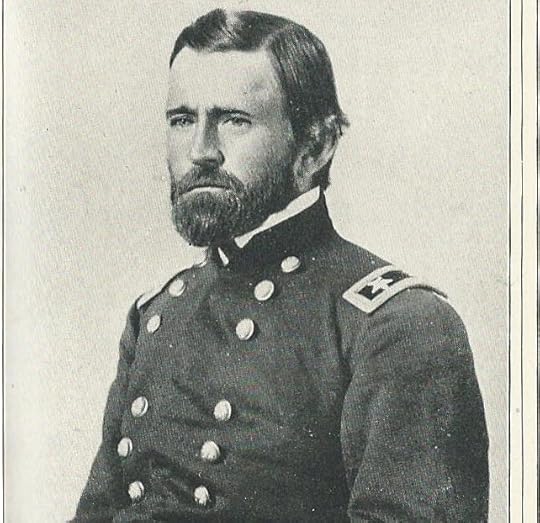

Ulysses S. Grant, before Vicksburg.

Ulysses S. Grant, before Vicksburg.Grant was asked if the lawmakers could address his troops. He welcomed a speech from McClernand, whose pro-Union sentiments were undeniable. Logan was another matter. Grant had noted Logan’s ambivalence about who was to blame for the war and the criticism directed at him by the Republican press. Some editors, Grant wrote, “were very bitter in their denunciations of his silence.”

Grant need not have worried. Logan defended the Stars and Stripes with passion and eloquence.

“Officers and men gathered in front of the grandstand in the free and easy democratic way characteristic of your true militiaman, and Logan made us a ringingly loyal speech,” one witness recalled. Logan’s oration “has he had hardly equaled since in force and eloquence,” Grant remembered in his memoirs. “It breathed a loyalty and devotion to the Union which inspired my men to such a point that they would have volunteered to remain in the army as long as an enemy of the country threatened to bear arms against it. They entered the United States service almost to a man.”7

The speech represented a watershed moment in Logan’s career. As neutrality gave way to support for the Union, his rise to greatness had begun.

Logan returned to Washington and witnessed the Union debacle at the first battle of Manassas. Back in Illinois, he raised an infantry regiment after a stirring speech at Marion in which he declared “The time has come when a man must be for or against his country, not for or against his state. … I for one will stand or fall for this Union, and shall this day enroll for the war. I want as many of you as will to come with me. If you say ‘No,’ and see the best interests of your homes and your children in another direction, may God help you.”8

Logan’s speech roused the crowd gathered to hear him and highlighted the shifting views in a region that once tilted toward the Confederacy. But not everyone was similarly swayed. The war cleaved Logan’s family. His mother vowed never to speak to him. His sister volubly denounced Logan as he marched past in Murphysboro, Ill., prompting Logan’s wife, Mary, to throw a punch and a chair at her sister-in-law.9

Logan joined Grant’s push south along the Mississippi and fought with his regiment at Belmont and Fort Donelson, where his troops “fought like veterans who had never had any other occupation” and he was wounded. While recovering, Logan was promoted to the rank of brigadier general.10

Over the next two years, he served with distinction as Grant tightened his stranglehold on the Confederacy. Whatever hesitancy he once had about the Union cause evaporated in the heat of combat. “We constitute the military arm of the Government,” he told his troops in February 1863. Duty required them to defend the “temple of Liberty” as it was being “shaken to the very center by the ruthless blows of traitors who have desecrated our flag” and “destroyed our peace.” 11

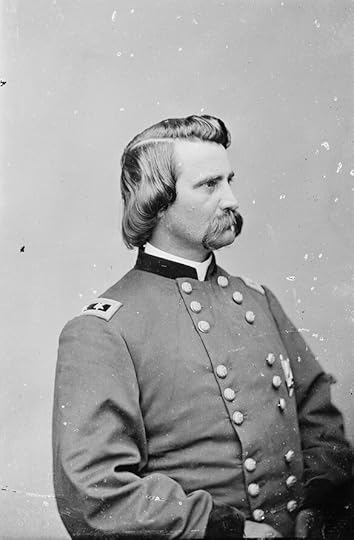

Gen. John A. Logan in uniform. Library of Congress.

Gen. John A. Logan in uniform. Library of Congress.Logan’s performance in combat earned a salute from the Chicago Tribune. The newspaper that labeled him “Dirty Work Logan” before war hailed his service and evolution into a wholehearted champion of the Union. The Tribune declared that “since this war broke out, and since Gen. Logan assumed the patriot’s part, and pushed gallantly into the thickest and hottest of the fight, we have conceived and expressed admiration for his qualities as a man and a lover of his country that we have never felt before.”

The Tribune remained uncertain about his partisan loyalties. But there was no doubt about his devotion to the Union cause:

Earnest, ready, untiring, vigilant, full of pluck, abounding in patriotism, confident of final success, and willing, whether success or failure comes, to do his whole duty because his country commands, he has become the pet and boast of the army to which he belongs; and we only re-echo the opinion of his superior, when we say that ‘he is a whole division in himself.'” 12

Not everyone in uniform shared the newspaper’s admiration. General William Tecumseh Sherman regarded Logan and General Frank P. Blair Jr. with skepticism. They possessed “great courage and talent,” Sherman wrote in his memoirs, but were “politicians by nature and experience” viewed with scorn by regular officers. After the death of General William McPherson in 1864 as Union forces closed in on Atlanta, Sherman declined to appoint Logan as McPherson’s successor to lead the Army of the Tennessee.

An astute judge of character, Sherman saw that the war for Logan was simultaneously a military and political conflict and did not approve of the commingled priorities. He noted with displeasure that after the Union capture of Atlanta, Logan and Blair “went home to look after politics.”13

Logan’s decision to return home and campaign for Abraham Lincoln’s re-election in 1864 marked a crucial step in his political journey. His days as a Democrat were over. “There are no party ties to bind me now,” he declared in a lengthy speech delivered in Carbondale on Oct. 1. “The only ties I acknowledge are those that bind me to the Stars and Stripes.” Logan emphasized preservation of the Union and made no reference to enslavement. He reviled so-called Peace Democrats who favored accommodation with secessionists to end the war. Acknowledging that he opposed Lincoln’s election in 1860, Logan now supported his re-election because “he has endeavored to sustain the government honestly and faithfully.”

The next step was inevitable. After the war, Logan joined the Republican Party and was elected to Illinois’s at-large seat in Congress. With senators chosen then by state legislators, the election made the already well-known general the only directly elected statewide member of Illinois’s congressional delegation.

The votes had barely been counted when reports appeared in the press linking Logan to plans to impeach President Andrew Johnson. Logan quickly denied any involvement in impeachment efforts,14 but the rumors highlighted the fraught political environment in Washington and foreshadowed Logan’s partisan posture.

Back on Capitol Hill for the first time since he resigned his House seat in 1862, Logan aligned himself with Republican radicals who favored a sweeping overhaul of Southern society that would guarantee once-enslaved Black men and women civil and political rights. Campaigning for Republicans in Ohio in 1867, he made the then-controversial case for extending the right to vote for formerly enslaved Black men by linking it to the military experience of white Union Army veterans:

“You will remember the times we were called to go against rebel bayonets; you remember the many battles through which you have passed, and you ought to remember … the men at the South who were your friends. … Now I appeal to you as honest men if you ever saw a Black man [in the] South who was not loyal to the government?15

In addition to informing Logan’s views on Reconstruction, honoring the memory of the war became a personal cause and provided an important source of political muscle. In May 1866, Logan spoke at a “Decoration Day” observance at a Carbondale, Ill., military cemetery that numbered among the ceremonies that led to the annual observance of the Memorial Day holiday honoring fallen veterans of U.S. wars. He belonged to the Society of the Army of the Tennessee and joined the new Grand Army of the Republic in 1866. As commander of the GAR in 1868, Logan ordered local chapters to decorate the graves of fallen Union soldiers on May 30.16

Logan’s Memorial Day directive followed another noteworthy order issued earlier in the year. In the tense days that followed President Andrew Johnson’s firing of Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, Logan ordered GAR members to stand guard around the White House and War Department, and he offered Stanton more than 100 veterans who would act as a personal guard. Stanton declined the offer.17 Logan served as one of the House prosecutors during Johnson’s impeachment trial in the Senate.

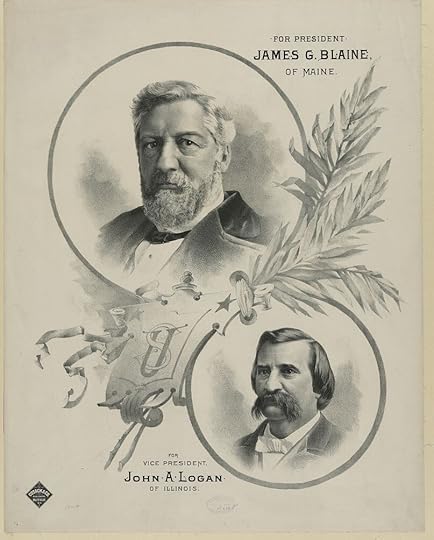

Logan remained a prominent national figure through the Grant administration and into the 1880s. He joined Republican “Stalwarts” led by Sens. Roscoe Conkling of New York and J. Donald Cameron of Pennsylvania in the unsuccessful effort to nominate Grant at the 1880 Republican convention in Chicago for an unprecedented third term as president. Four years later, Logan sought the nomination himself but ended up as the party’s vice-presidential candidate on the ticket with James G. Blaine.

Logan ran on the 1884 Republican ticket as vice-presidential candidate with James G. Blaine. Library of Congress.

Logan ran on the 1884 Republican ticket as vice-presidential candidate with James G. Blaine. Library of Congress.At his death in 1886, the New York Times reminded readers for whom the Civil War was a fading memory that the conflict remained “the most signal event” in the memory of millions of their fellow citizens. For them, Logan’s appeals to patriotism were genuine — and compelling.

“It is easy for those who knew Gen. Logan only as a politician and Republican leader in the House and Senate to feel that his prominence, his influence, his unquestioned popularity, were a curious evidence of an unreasoning bias in the partisan mind,” the Times acknowledged. But for the generation of men and women who “shared the stress of that sore trial in which he cast his lot with the Union, and who remember also to what deep passion of patriotism his heroic service appealed during those four years, the charm of his name is no mystery.”18

“The Life of Gen. Logan: a sketch of the dead soldier-statesman’s career,” Chicago Tribune, Dec. 27, 1886, p. 3. ︎U.S. Congress, House, Congressional Globe, Thirty-Sixth Congress, Dec. 9, 1859, p. 85.

︎U.S. Congress, House, Congressional Globe, Thirty-Sixth Congress, Dec. 9, 1859, p. 85.  ︎“Egypt in Congress,” Chicago Tribune, Dec. 12, 1859, p. 2.

︎“Egypt in Congress,” Chicago Tribune, Dec. 12, 1859, p. 2.  ︎“To John A. Logan,” Illinois Journal, Feb. 15, 1861, p. 1.

︎“To John A. Logan,” Illinois Journal, Feb. 15, 1861, p. 1.  ︎Gary Ecelbarger, Black Jack Logan: An Extraordinary Life in Peace and War (Guilford, Conn., The Lyons Press, 2005), p. 73. Hereafter referred to as Ecelbarger.

︎Gary Ecelbarger, Black Jack Logan: An Extraordinary Life in Peace and War (Guilford, Conn., The Lyons Press, 2005), p. 73. Hereafter referred to as Ecelbarger.  ︎“The Seat of War at the West,” New York Herald, June 12, 1861, p. 5; “Egypt Speaks for the Union. What Position does John Logan Occupy?” Daily Illinois State Journal, June 18, 1861, p. 2.

︎“The Seat of War at the West,” New York Herald, June 12, 1861, p. 5; “Egypt Speaks for the Union. What Position does John Logan Occupy?” Daily Illinois State Journal, June 18, 1861, p. 2.  ︎Ecelbarger, pp. 78-79; U.S. Grant, Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant (New York: Da Capo Press, 1982), p. 125.

︎Ecelbarger, pp. 78-79; U.S. Grant, Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant (New York: Da Capo Press, 1982), p. 125.  ︎Mary Simmerson Cuninngham Logan, Reminiscences of a Soldier’s Wife (New York: C. Scribner’s and Sons, 1913, p. 98). Hereafter referred to as Mary Logan.

︎Mary Simmerson Cuninngham Logan, Reminiscences of a Soldier’s Wife (New York: C. Scribner’s and Sons, 1913, p. 98). Hereafter referred to as Mary Logan.  ︎Ecelbarger, pp. 88-89.

︎Ecelbarger, pp. 88-89.  ︎“The Ft. Donelson Victory,” Chicago Tribune, Feb. 18, 1862, p. 1; Ibid., “The Latest News by Telegraph,” March 22, 1862.

︎“The Ft. Donelson Victory,” Chicago Tribune, Feb. 18, 1862, p. 1; Ibid., “The Latest News by Telegraph,” March 22, 1862.  ︎Ibid., “The Voice of Patriotism,” Chicago Tribune, Feb. 21, 1863.

︎Ibid., “The Voice of Patriotism,” Chicago Tribune, Feb. 21, 1863.  ︎Ibid., “Gen. John A. Logan,” May 27, 1863, p. 2

︎Ibid., “Gen. John A. Logan,” May 27, 1863, p. 2  ︎William T. Sherman, Memoirs of General William T. Sherman, Vol. 2 (New York: Appleton & Co., 1886), pp. 85, 130.

︎William T. Sherman, Memoirs of General William T. Sherman, Vol. 2 (New York: Appleton & Co., 1886), pp. 85, 130.  ︎After Illinois had been awarded an additional seat in the House in 1862, the state legislature created an “at-large” House seat rather than redraw its existing 13 congressional districts. “Congressman At Large,” New York Tribune, Nov. 14, 1866, p. 4; Ibid., Nov. 23, 1866, p. 4.

︎After Illinois had been awarded an additional seat in the House in 1862, the state legislature created an “at-large” House seat rather than redraw its existing 13 congressional districts. “Congressman At Large,” New York Tribune, Nov. 14, 1866, p. 4; Ibid., Nov. 23, 1866, p. 4.  ︎Ecelbarger, p. 246; “Earnest Words from Gen. Logan,” Nashville, Ill., Journal, Oct. 4, 1867, p. 4.

︎Ecelbarger, p. 246; “Earnest Words from Gen. Logan,” Nashville, Ill., Journal, Oct. 4, 1867, p. 4.  ︎Ecelbarger, pp. 236-238; “Memorial Day: The Origins of Memorial Day,” U.S. Army Center of Military History [https://history.army.mil/Research/Ref...]

︎Ecelbarger, pp. 236-238; “Memorial Day: The Origins of Memorial Day,” U.S. Army Center of Military History [https://history.army.mil/Research/Ref...]  ︎David O. Stewart, Impeached (New York: Simon & Schuster Paperbacks, 2009), p. 141.

︎David O. Stewart, Impeached (New York: Simon & Schuster Paperbacks, 2009), p. 141.  ︎“John A. Logan,” New York Times, Dec. 27, 1886, p. 4.

︎“John A. Logan,” New York Times, Dec. 27, 1886, p. 4.  ︎

︎ Coming Oct. 1: The Partisans: James G. Blaine, Roscoe Conkling, and the Politics of Rivalry and Revenge in the Gilded Age. Published by Edinborough Press.

Coming Oct. 1: The Partisans: James G. Blaine, Roscoe Conkling, and the Politics of Rivalry and Revenge in the Gilded Age. Published by Edinborough Press.