“A new orbit:” How James B. Weaver launched his partisan odyssey

First in a series that looks at some of the prominent figures of the hyper-partisan Gilded Age who switched parties — often more than once and in one case with tragic consequences.

At the end of a political career in which he switched parties several times, ran twice for president, served three terms in Congress, and allied himself with William Jennings Bryan, Iowa populist James B. Weaver looked back on the years when everything began to change.1

Born in 1833 in Ohio, Weaver moved with his family across the Midwest, to Michigan and ultimately to Iowa, where his father took a stab at farming before moving to Bloomfield, the county seat of Davis County.

Abram Weaver brought his loyalty to the Democratic Party with him as he and his family migrated west and passed it on to his son. In what he remembered as his political debut, Weaver recalled besting future Republican congressman and secretary of war George McCrary in a debate about the Kansas-Nebraska Act.

But the younger Weaver’s political outlook altered dramatically by the end of the decade. After a stint at law school in Cincinnati studying under Whig jurist Bellamy Storer, Weaver shifted his loyalties to the new Republican Party. Those were the years of the Lecompton Constitution and “Bleeding Kansas,” the Dred Scott decision and the brutal caning of Senator Charles Sumner on the Senate floor by South Carolina Democrat Preston “Bully” Brooks.

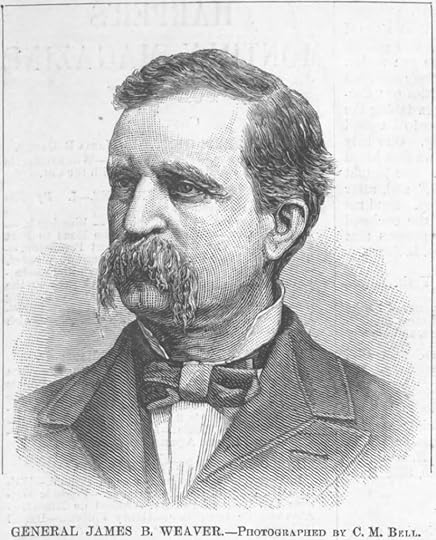

James B. Weaver in 1880. Harper’s Weekly.

James B. Weaver in 1880. Harper’s Weekly.Reminiscing about this tumultuous period in an unpublished biographical memorandum written toward the end of his life, Weaver recalled that the “world was changing and searching out a new orbit.”

Over the next several weeks, I’ll be writing about figures like Weaver whose partisan and ideological affiliations veered in new directions in response to the wrenching changes wrought by civil war and industrialization. Some settled into stable partisan orbits; others careened from one party to another. In addition to Weaver, I’ll be writing about:

Benjamin Butler of Massachusetts, who evolved from a Democrat who supported Jefferson Davis for the party’s 1860 presidential nomination into a radical Republican who favored vigorous federal enforcement of civil and voting rights legislation in the South before leaving the party over monetary questions.John Logan of Illinois, like Butler a Democrat at the start of the war who embraced the Union cause. Logan served as a Union general during the war and became a staunch Republican. Once he switched parties he stayed put and became a party power broker.Albert Parsons experienced the most dramatic political evolution and suffered the most extreme consequences. The Texas-born anarchist served in the Confederate army and joined the Republican Party after the war before he moved to Chicago to become a radical supporter of labor. Parsons was hanged in 1887 after being convicted of complicity in the death of a Chicago police officer during the Haymarket Riot of 1886.For Butler, Logan and Parsons, it was the Civil War and its aftermath that launched them in new political directions. Weaver’s search for a “new orbit” began as the partisan divisions of the antebellum era broke down and a new party emerged in its place.

Like Abram Weaver, Iowa’s partisan loyalties in the 1850s were firmly Democratic. At the beginning of the decade, two Democrats — Augustus Caesar Dodge and George Wallace Jones — represented Iowa in the Senate. Democratic presidential candidates Lewis Cass, Franklin Pierce and James Buchanan carried the state in 1848,1852 and 1856.

While the young Weaver left for Cincinnati with his father’s Democratic allegiance, he returned with a new perspective. Cincinnati was a hotbed of agitation over slavery. Storer aligned with abolitionists and urged his students to apply the precepts of the Bible to their legal careers. Weaver came home fired by anti-slavery idealism.

The Iowa to which he returned was undergoing profound political change. The Kansas-Nebraska Act, which raised the ominous prospect of slavery being permitted in western territories, roiled the state. As the Whig Party withered and died, anti-slavery Democrats joined with like-minded former Whigs and abolitionists to rally around a new political entity, the Republican Party.

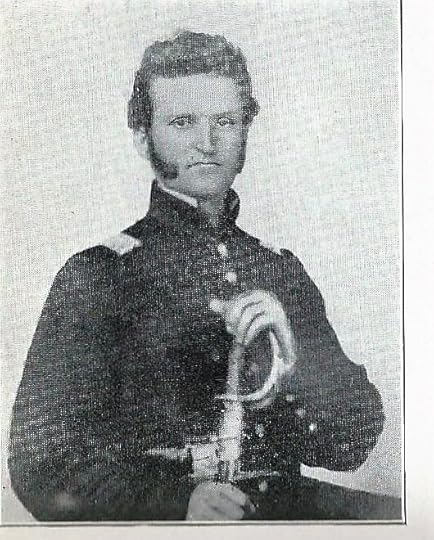

A young James B. Weaver in the uniform of the Union Army.

A young James B. Weaver in the uniform of the Union Army.The Supreme Court’s infamous Dred Scott ruling that Black Americans lacked standing as citizens further inflamed public opinion in Iowa. In an address to state legislators in 1858, Iowa Gov. James B. Grimes expressed the hope that “you will explicitly declare that you will never consent that this state shall become an integral part of a great slave republic, by assenting to the abhorrent doctrines of the Dred Scott decision, let the consequences of dissent be what they may.”2

Weaver leaped enthusiastically into the ranks of anti-slavery Republicans and spoke across southern Iowa in favor of the new party. According to the late William Safire, he added to the American political lexicon when he denounced the brutal assault of an Iowa evangelist who incurred the wrath of white Texans for preaching to enslaved Black men and women. The preacher returned to Iowa with the blood-soaked garment he was wearing when he was whipped. “Under this bloody shirt we propose to march to victory,” Weaver declared.3

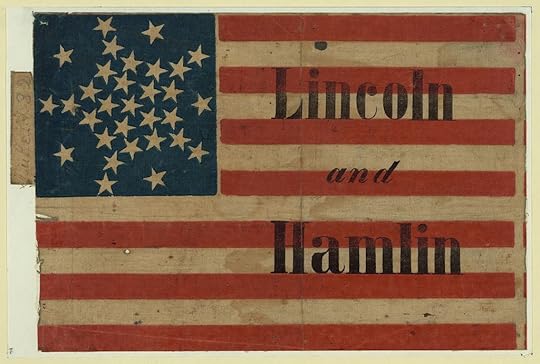

In 1860, Weaver joined the Iowa delegation in Chicago where Republicans nominated Abraham Lincoln for president and campaigned for him back in Iowa. At a rally close to the border with slave-state Missouri, Weaver and an associate rose to speak for Lincoln when a fight broke out. Order was restored after another person at the meeting threatened to “mash the head of the first man who tried to disturb the meeting.” Weaver and his comrade made their case for Lincoln and left for friendlier environs. Lincoln carried Iowa to inaugurate a long period of Republican dominance in the state.

A Lincoln-Hamlin poster from 1860. Library of Congress.

A Lincoln-Hamlin poster from 1860. Library of Congress.After Southern rebels fired on Fort Sumter in 1861, Weaver joined an Iowa infantry regiment and fought at Fort Donelson and Shiloh. He was promoted to colonel in the field, received a brevet appointment as brigadier general after returning home, and was elected as a district attorney. His political prospects seemed bright. But then things started to go wrong.

Weaver was an ardent supporter of prohibition, but Republican elders — with an eye on German and Irish voters in the state — resisted identifying too closely with temperance and deemed Weaver too extreme on the issue. In 1874, he lost the Republican nomination to Congress at a district convention. A year later, he was the favorite to win the party’s nomination for governor but lost when a last-minute convention stampede turned to Samuel Kirkwood. He was “supposed to be the coming man,” an Iowa newspaper observed. In 1875 it appeared his political career had hit a dead end.

Instead of trimming his sails on temperance to win the support of the Republican establishment, Weaver turned to another party to crusade on another issue. Following the Panic of 1873 and the ensuing depression, Americans divided sharply on monetary policy questions. Conservatives in both parties favored deflationary “hard money” policies linking the dollar to the gold standard, while others demanded “soft money” paper currency whose inflationary qualities won the support among debt-laden farmers.

Weaver enlisted in the Greenback-Labor Party as it seemed poised to emerge as Republicans as a party of reform just as Republicans had 20 years earlier. The new party embraced a broad agenda that focused primarily on soft money but also included calls for banning child labor and the regulation of working conditions. It condemned “as most dangerous the efforts everywhere manifest to restrict the right of suffrage” and demanded an income tax.

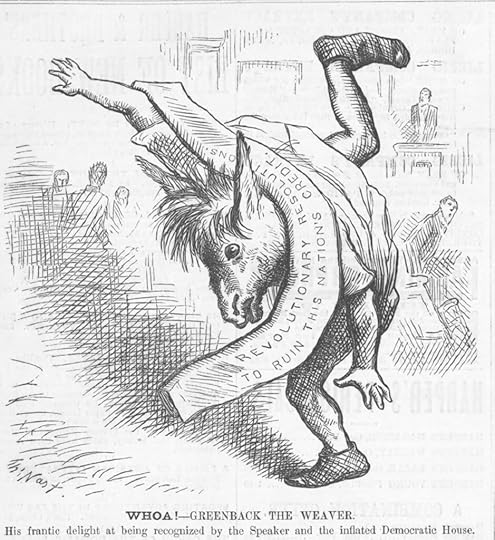

Harper’s Weekly cartoonist Thomas Nast didn’t think much of Weaver and portrayed him as the donkey Nick Bottom from Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dre

am.

Harper’s Weekly cartoonist Thomas Nast didn’t think much of Weaver and portrayed him as the donkey Nick Bottom from Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dre

am.

Iowans elected Weaver to Congress in 1878 and he quickly emerged as the party’s leading spokesman. In the House, he campaigned tirelessly to elevate currency issues and succeeded, with the help of Republican leader James A. Garfield, in forcing a debate on Greenback currency resolutions designed to put Democrats on the hot seat. In July 1880, the third party nominated Weaver for president.

If Weaver hoped the Greenbacks would replicate the success of Republicans, he was sorely mistaken. Plagued by internal dissent and dominated by a collection of visionaries and cranks, the party performed poorly in the presidential election in which Republican candidate James A. Garfield narrowly defeated Democrat Winfield Scott Hancock. The third party never recovered and faded from view before the decade was out. Weaver returned to Congress with the help of Democrats in 1884 and was reelected to a second term, but the reform movement stalled and he was defeated in 1888.

Weaver cast about for another cause. He joined Sooners who emigrated to the Oklahoma Territory but failed to establish himself as their leader. He returned to Iowa and edited a weekly newspaper that championed the cause of the embattled farmer. Meanwhile, a new movement of Agrarian radicals who emerged on the Texas plains and would soon sweep through the agricultural regions of the Midwest, Far West and South. As the movement evolved into a political party it embraced the name Populist.

Weaver gravitated to the Populists, who amplified the soft money position of the Greenback-Labor Party, echoed Greenback support of a graduated income tax, and called for government ownership of the railroads. He wrote a book outlining the Populist critique of the economy and American politics. Weaver mounted a second campaign for the White House as the Populist presidential candidate in 1892 and carried four states — the first third-party candidate to do so since 1860.

Four years later, though, Weaver decided to convince his party to endorse the Democratic presidential nominee, William Jennings Bryan. Weaver regarded Bryan as a powerful spokesman for the issues Populists cared about and believed that advancing the cause was more important than perpetuating the third party. The Populists nominated Bryan as their candidate but thereafter withered into obscurity. Weaver eventually followed Bryan into the Democratic Party.

James B. Weaver (left) and William Jennings Bryan in 1896 as seen on the cover of Puck. Library of Congress.

James B. Weaver (left) and William Jennings Bryan in 1896 as seen on the cover of Puck. Library of Congress.For many politicians in the 19th century, the Civil War proved to be the decisive factor in determining their partisan allegiances. While many who left the Democratic Party to become Republicans stayed with the party of Lincoln, Weaver pursued opportunities for political and economic reform whenever they appeared. His formative political experience came in the tumultuous years before the Civil War, when the Whig Party died and the Republicans — attracting anti-slavery Democrats, Whigs and radical abolitionists — emerged as a new force in American politics. Weaver was a Democrat in his youth, a Republican as a young man, and a Greenback and Populist in middle age before finally returning to the Democratic Party in his final years. His search for a “new orbit” began as Americans lurched toward civil war and continued into the 20th century.

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Skirmisher: The Life, Times, and Political Career of James B. Weaver, won the Benjamin F. Shambaugh Award from the State Historical Society of Iowa in 2009 as “the most significant book on Iowa history published in the previous year.” It is available at amazon.com. My latest book, The Partisans: James G. Blaine, Roscoe Conkling, and the Politics of Rivalry and Revenge in the Gilded Age, is coming soon from Edinborough Press.

Skirmisher: The Life, Times, and Political Career of James B. Weaver.

Skirmisher: The Life, Times, and Political Career of James B. Weaver. Congress and the King of Frauds: Corruption and the Credit Mobilier Scandal at the Dawn of the Gilded Age

Congress and the King of Frauds: Corruption and the Credit Mobilier Scandal at the Dawn of the Gilded Age Coming soon: The Partisans: James G. Blaine, Roscoe Conkling, and the Politics of Rivalry and Revenge in the Gilded AgeUnless otherwise noted, this account of Weaver’s experiences in the 1850s is based on my biography: Skirmisher: The Life, Times, and Political Career of James B. Weaver (Edinborough Press).

Coming soon: The Partisans: James G. Blaine, Roscoe Conkling, and the Politics of Rivalry and Revenge in the Gilded AgeUnless otherwise noted, this account of Weaver’s experiences in the 1850s is based on my biography: Skirmisher: The Life, Times, and Political Career of James B. Weaver (Edinborough Press).  ︎Journal of the House of Representatives of the Seventh General Assembly of the State of Iowa (Des Moines, J. Teesdale, State Printer, 1858), p. 29.

︎Journal of the House of Representatives of the Seventh General Assembly of the State of Iowa (Des Moines, J. Teesdale, State Printer, 1858), p. 29.  ︎William Safire, Safire’s Political Dictionary (Oxford University Press, 2008), p. 62.

︎William Safire, Safire’s Political Dictionary (Oxford University Press, 2008), p. 62.  ︎

︎