“A new orbit”: The unique political compass of Benjamin F. Butler

Colorful and controversial, the mercurial lawyer from Lowell, Mass., pursued a political career governed by a synthesis of Hamiltonian and Jeffersonian principles. The second installment in an occasional series on Gilded Age party-switchers.

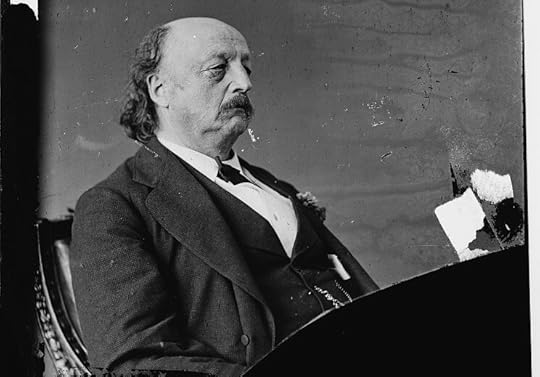

Benjamin F. Butler. Brady-Handy photograph collection, Library of Congress.

Benjamin F. Butler. Brady-Handy photograph collection, Library of Congress.Nobody could mistake Benjamin Franklin Butler of Massachusetts for a run-of-the-mill politician, not even in the 19th century.

He was born cross-eyed. His left eyelid drooped. Black hair tumbled from the back of his balding head. When he walked up the aisle in the House of Representatives, his stride was likened to a “bass walking on its tail.” He delighted in discord and demonstrated a genius for creating — and thriving in — controversy.

“General Butler was not eloquent, but he was savage — savage as a meat ax,” Republican representative Julius Caesar Burrows of Michigan recalled, referring to Butler by his Civil War rank. “It was not what he said that made the House always listen to him with rapt attention, but the expectation of what he was going to say. He was like a volcano — always smoking and always giving a hint of an impending eruption.”1

Butler stood out not only because of his unique appearance and proclivity for political pugilism but because he charted a dramatically unconventional partisan path. Before the Civil War, the lawyer from Lowell was a Democrat allied with Jefferson Davis of Mississippi, the future president of the Confederacy. When war broke out, Butler distinguished himself as an ardent Union loyalist whose refusal to return Black people to their Southern enslavers opened the door for Black men to serve in the Union Army. Davis, his one-time ally, called for Butler’s execution after Butler declared that women in New Orleans who insulted Northern soldiers would be treated as prostitutes.2

Butler became a prominent Republican radical in Congress after the war but returned to the Democratic Party to win election as governor of Massachusetts in 1882. He ran for president two years later as the nominee of the Greenback-Labor Party. Like many Gilded Age political figures, he developed a reputation for corruption and sleazy self-enrichment.

Butler sympathized with enslaved Black Southerners who endured terrorist violence when slavery ended. He championed mill workers and campaigned to improve working conditions in the nation’s factories.3 He fought for his beliefs with fiery passion.

Ben Butler on the House floor in 1871 as portrayed in the Wheeling Daily Register.

Ben Butler on the House floor in 1871 as portrayed in the Wheeling Daily Register.Contemporaries seized on this latter characteristic to denigrate and dismiss him. Journalist George Alfred Townsend called Butler a demagogue. “Never in a republic, has one man succeeded in making himself so terrible,” Townsend wrote. “Appealing always to the instinct of fear, he has thus far succeeded beyond the power of talents, of social influence, of wealth, or of popularity, in putting himself at the head of every assault.”4

Somewhat more judiciously, Butler rival James G. Blaine reached the same conclusion.

“He exhibited an extraordinary capacity for agitation, possessing in a high degree what John Randolph described as the ‘talent for turbulence,'” Blaine wrote in 1885. “The stormier the scene, the greater his apparent enjoyment and the more striking the display of his peculiar ability.”5

Distracted by the pyrotechnics, Townsend and the usually astute Blaine failed — like so many others — to discern the underlying philosophical principles that guided Butler during a career that began before the Civil War and continued until his death in 1893.

At its simplest, Butler’s political lodestar was sympathy for the downtrodden born of his hardscrabble beginnings and lifelong antipathy for the bluestocking aristocracy of Massachusetts. “I must always be with the under dog in the fight,” he declared. “I can’t help it. I can’t change, and on the whole I don’t want to.”6

Principle and pugnacity guided Butler throughout his life. Born in 1818 in New Hampshire, Butler faced adversity at a young age. His father died when he was five months old. Butler and his mother moved to Lowell, where she worked as a cleaning woman at a factory dormitory. He briefly attended Exeter Academy but received most of his schooling in Lowell. In both locations, he was remembered as much for his prickly demeanor as his academic prowess.7

He took up the law as a young man and became a successful criminal attorney in Lowell. He earned a commission as a brigadier general of the state militia and became active in Democratic politics. In 1857, Davis, then secretary of war for President James Buchanan, put Butler on West Point’s Board of Visitors. When Democrats gathered in Charleston in 1860 to nominate a presidential candidate, Butler backed Davis in the mistaken belief that he was a moderate on slavery who would be acceptable to fire-eating Southerners and anti-slavery Northerners.8

Ben Butler in uniform. Library of Congress.

Ben Butler in uniform. Library of Congress.The attack on Fort Sumter in April 1861 disabused Butler and countless other Americans of the idea that the emerging sectional conflict over slavery could be settled peaceably. Responding to a call from Secretary of War Simon Cameron for troops to protect Washington, Butler arrived in Maryland and acted vigorously to keep the state from seceding. He threatened legislators with arrest if they voted for secession, seized the state’s Great Seal to prevent legislation from becoming law, and took control of Baltimore to keep local rebel sympathizers from running amok.9

Butler remained in uniform throughout the war, but his record as a commander was undistinguished at best and dismal at worst. Hesitancy and poor decision-making led to defeats at Big Bethel, the James River, and Wilmington, N.C. “As a general in the field, the military critics do not accord him any high standing,” the New York Times wrote.10

But Butler’s reputation was shaped more dramatically by his gradual awakening to the injustice of slavery and his hostility toward secessionists. The politician who had allied himself with Davis before the war became the Union commander who in 1861 refused to return Black men and women to their enslavers when they fled to the Union lines. Butler called them “contraband of war.” Butler’s action, Blaine wrote, “solved a question of policy which otherwise might have been fraught with serious difficulty. In the presence of arms, the Fugitive-slave law became null and void, and the Dred Scott decision was trampled under the iron hoof of war.”11

As the military governor of New Orleans after its capture in April 1862, Butler declared that any female who “by word, gesture, or other movement” insulted Union Army troops would be “treated as a woman of the town, plying her vocation.” The order followed a series of provocative incidents, including the emptying of a chamber pot on Naval Capt. David Farragut, and provoked a storm of international outrage.

“Men of the South, shall our mothers, wives, daughters and sisters be thus outraged by ruffianly soldiers of the North?” Confederate Gen. G.T. Beauregard fulminated. Davis ordered Butler’s execution without trial were he captured. In Britain, Prime Minister Palmerston denounced the order as a blot on the honor of Anglo-Saxon arms. But Butler’s order worked, historian Francis Russell noted. The provocations ceased, and no women were arrested. Nevertheless, the episode made Butler persona non grata throughout the South for the rest of his life.12

Allegations of corruption further marred Butler’s reputation. He was alleged to have smuggled stolen silver spoons out of New Orleans in a coffin while he ran the city. The accusation was untrue, but the story stuck. The unflattering nickname “Spoons” trailed Butler for the rest of his career.13

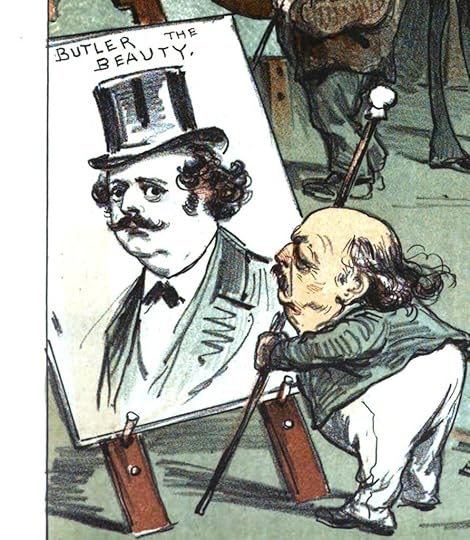

A Puck cartoon from August 1881 shows Ben Butler as he would have liked to be seen.

A Puck cartoon from August 1881 shows Ben Butler as he would have liked to be seen.After the war, all traces of Butler’s antebellum Democratic loyalties vanished. He returned to Massachusetts and was elected to Congress as a Republican in 1866. He quickly emerged as a prominent radical Republican critic of President Andrew Johnson’s lenient approach to Reconstruction and acted as Johnson’s lead prosecutor during his impeachment trial in 1868.

With the fate of Johnson’s presidency on the line, Butler pursued a characteristically aggressive course. He sharply questioned witnesses, raised numerous minuscule evidentiary questions, and insulted Johnson’s lawyers. Butler managed to keep the unwieldy seven-member prosecution team on the attack but “seems to have no power in conciliation,” Townsend wrote in the Chicago Tribune. That shortcoming cost the prosecution the support of key Republicans,14 and helped Johnson escape conviction by one vote.

Moderate and conservative Republicans had additional reasons to scorn the combative Lowell lawmaker. Butler pushed for aggressive federal action to protect the civil and political rights of once-enslaved Black Southerners targeted by Ku Klux Klan and other white terrorists. The legislation backed by Butler would have enabled the federal government to suspend habeus corpus and use federal troops to restore order in Southern states where chaos reigned. Butler blasted the dithering of his colleagues in March 1875 when the House Republican leadership connived with Democrats to permit an all-night filibuster that doomed the bill.

“When they hear the shriek of ‘murder,’ and see the widowed wife and orphaned children coming north, fleeing white-leaguers and Ku-Klux raiders, I trust their sleep will be as sweet as it was on the night I was standing here for the safety of these poor creatures,” he said of his complacent colleagues.15 The bill passed, but too late for the Senate to act. Subsequent violence validated Butler’s warning.

His outspoken opposition to conservative monetary policies further antagonized leading Republicans. After the war, Butler defended the use of paper money to pay off bonds used to finance the war effort. “Why, it is said we must not interfere with the national banks because they patriotically helped us during the war,” he said in 1867. “On the contrary, they helped themselves, not us.”16 While Butler’s support of paper money and hostility to banks reflected the views of a diverse group of Republicans, the position was anathema to party leaders, including Blaine.

On some issues, Butler remained a loyal Republican. He energetically defended fellow Massachusetts Republican Oakes Ames on the House floor when Ames was accused of malfeasance in the Credit Mobilier affair and other members of the party — although sympathetic to Ames — were unwilling to stand up for their colleague. But Butler committed a grievous political blunder when he succeeded in getting Congress to approve a pay raise for itself. Public fury with what became known as the “salary grab” drove scores of Republicans to defeat — including Butler — and allowed Democrats to take control of the House.

Butler returned to Congress in 1876 as a Republican but soon broke with the party for good. He ran twice for governor of Massachusetts as a Democrat and was elected for a single term in 1882. Two years later, he was the Greenback-Labor Party’s candidate for president but performed poorly, even by the standards of a third-party candidate. His days in politics were over. He died in 1893.

A “presidential valentine” for Ben Butler published in Puck, Feb. 13, 1884.

A “presidential valentine” for Ben Butler published in Puck, Feb. 13, 1884.Toward the end of his life, Butler explained that his political career had been guided by the legacy of two Founding Fathers seen as being at opposite ends of the political spectrum.

“I declare my political convictions to be these,” Butler wrote in his autobiography, published in 1892. “As to the powers and duties of the government of the United States, I am a Hamiltonian Federalist. As to the rights and privileges of the citizen, I am a Jeffersonian Democrat.” Every citizen, he believed, possessed the right to “call on either the State, or the United States, or both, to protect them in equality of powers, equality of rights, equality of privileges, and equality of burdens under the law, by carefully and energetically enforced provisions of equal laws justly applicable to every citizen.”17

Butler believed the federal government needed to be strong enough — and active enough — to protect the freedoms and aspirations of American citizens. Liberals of the 20th century made this synthesis of Hamiltonian and Jeffersonian principles their watchword. But in the second half of the 19th century, it was a unique approach to politics — and too much for most Americans.

After his death, the Washington Post took note of Butler’s idiosyncratic career. The newspaper praised “the fervor of his patriotism and the “depth of his sympathies with humanity” while noting his “somewhat rugged and uncouth characteristics.” Butler “was always a striking and forceful personality, for whom the American people had great admiration, and whom but for the peculiar and heterodox drift of his political beliefs (ital added), they would have delighted to honor with the highest honors in their gift.”18

In other words, America wasn’t ready for Ben Butler.

“Sorrow of the Veterans,” Washington Post, Jan. 12, 1893, p. 1. ︎Bruce Catton, Terrible Swift Sword (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday and Co., 1963), p. 359.

︎Bruce Catton, Terrible Swift Sword (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday and Co., 1963), p. 359.  ︎Francis Russell, “Butler the Beast?” American Heritage, April 1968, Vol. 19, Issue 3. Hereafter referred to as Russell.

︎Francis Russell, “Butler the Beast?” American Heritage, April 1968, Vol. 19, Issue 3. Hereafter referred to as Russell.  ︎George Alfred Townsend, Washington Outside and Inside (Hartford, Conn., and Chicago, James Betts & Co., 1874), p. 374.

︎George Alfred Townsend, Washington Outside and Inside (Hartford, Conn., and Chicago, James Betts & Co., 1874), p. 374.  ︎James G. Blaine, Twenty Years of Congress Vol. 2 (Norwich, Conn., The Henry Bill Publishing Co., 1885), p. 289.

︎James G. Blaine, Twenty Years of Congress Vol. 2 (Norwich, Conn., The Henry Bill Publishing Co., 1885), p. 289.  ︎Governor Benj. F. Butler, “Argument Before the Tewksbury Investigation Committee,” Jukly 15, 1883, p. 29.

︎Governor Benj. F. Butler, “Argument Before the Tewksbury Investigation Committee,” Jukly 15, 1883, p. 29.  ︎Russell.

︎Russell.  ︎Ibid.

︎Ibid.  ︎Ibid.

︎Ibid.  ︎“Benjamin F. Butler,” New York Times, Jan. 12, 1893, p. 4.

︎“Benjamin F. Butler,” New York Times, Jan. 12, 1893, p. 4.  ︎James G. Blaine, Twenty Years of Congress Vol. 1 (Norwich, Conn., The Henry Bill Publishing Co., 1884), p. 369.

︎James G. Blaine, Twenty Years of Congress Vol. 1 (Norwich, Conn., The Henry Bill Publishing Co., 1884), p. 369.  ︎Catton, p. 359; James McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988, p. 552; “From Corinth and the South,” Chicago Tribune, May 26, 1862, p. 1; Russell.

︎Catton, p. 359; James McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988, p. 552; “From Corinth and the South,” Chicago Tribune, May 26, 1862, p. 1; Russell.  ︎Russell; William Dana Orcutt, “Ben Butler and the Stolen Spoons: The Documents in the Case, from His Unpublished “Private and Official Correspondence,” North American Review, Vol. 207, No. 746, Jan. 1918, pp. 66-80.

︎Russell; William Dana Orcutt, “Ben Butler and the Stolen Spoons: The Documents in the Case, from His Unpublished “Private and Official Correspondence,” North American Review, Vol. 207, No. 746, Jan. 1918, pp. 66-80.  ︎“Scenes at the Capitol During Impeachment,” Chicago Tribune, May 9, 1868, p. 2; David O. Stewart, Impeached: The Trial of Andrew Johnson and the fight for Lincoln’s Legacy (New York, London, Toronto, Sydney: Simon & Schuster, 2009, pp.170-171.

︎“Scenes at the Capitol During Impeachment,” Chicago Tribune, May 9, 1868, p. 2; David O. Stewart, Impeached: The Trial of Andrew Johnson and the fight for Lincoln’s Legacy (New York, London, Toronto, Sydney: Simon & Schuster, 2009, pp.170-171.  ︎U.S. Congress, House, Congressional Record, 43rd Congress, 1st session, Feb. 27, 1875, p. 1,906.

︎U.S. Congress, House, Congressional Record, 43rd Congress, 1st session, Feb. 27, 1875, p. 1,906.  ︎Butler’s congressional statement quoted in Benjamin F. Butler, Butler’s Book: A Review of His Legal and Political Career (Boston: A.M. Thayer & Co., 1892), p. 944.

︎Butler’s congressional statement quoted in Benjamin F. Butler, Butler’s Book: A Review of His Legal and Political Career (Boston: A.M. Thayer & Co., 1892), p. 944.  ︎Ibid., p. 86.

︎Ibid., p. 86.  ︎“The Late Gen. Butler,” The Washington Post, Jan. 12, 1893, p. 4.

︎“The Late Gen. Butler,” The Washington Post, Jan. 12, 1893, p. 4.  ︎

︎