“Wherever concealment is desirable, avoidance is advisable”

In the aftermath of his Andersonville speech, James G. Blaine suffered a blow to his reputation from which he never recovered.

The second of two parts

A cartoon from

Puck

published May 21, 1884, shows James G. Blaine as the pied piper of Hamelin with a tattoo reading “Mulligan letters” on his left leg. The cartoon illustrates how the correspondence haunted him eight years after it was revealed.

A cartoon from

Puck

published May 21, 1884, shows James G. Blaine as the pied piper of Hamelin with a tattoo reading “Mulligan letters” on his left leg. The cartoon illustrates how the correspondence haunted him eight years after it was revealed.The future looked bright for James G. Blaine in the weeks that followed his Andersonville speech. “He is today not only the acknowledged leader of” House Republicans “but he is the strongest and most popular man the party has in either house,” the St. Cloud Journal told its Minnesota readers. “His nomination” for president “would create an enthusiasm which could be called forth by no other candidate.”1

The good feeling would not last long. After stumbling in the opening weeks of the Forty-Fourth Congress, Democrats found their footing as they took aim at Republican corruption. With a little help from Blaine’s Republican rivals, Democratic scandal hunters turned their sights on the “magnetic man” from Maine.

Charges of malfeasance and wrongdoing offered a fertile field for a political party that had been out of power since before the Civil War. Allegations of sleazy dealings shadowed President Ulysses S. Grant’s administration from its earliest days. As Grant’s second term neared its end, those allegations escalated as an avalanche of scandal buried Cabinet officials and the president’s associates.

The scandals that enveloped the Grant administration included:

An investigation by Treasury Secretary Benjamin Bristow into an elaborate tax-avoidance scheme by whiskey distillers implicated associates of the president, including Grant’s aide and longtime friend Orville Babcock.The resignation of Secretary of War William Belknap in May 1876, hours before he was impeached by the House following an investigation into bribes he received from the proprietors of Indian trading posts.Efforts by Robert Schenck, the U.S. minister to Great Britain, to attract English investors in a California mining company in which he held stock.The finances of Navy Secretary George Robeson, whose lavish lifestyle seemed to exceed what he made as a member of the Cabinet.The resignation of Interior Secretary Columbus Delano, following revelations that his son attempted to exploit his father’s position for personal gain.2 James G. Blaine. Library of Congress.

James G. Blaine. Library of Congress.Blaine was next as whispers about his dabbling in the railroad frenzy of the late 1860s took tangible form in early 1876. Republican journalists Henry Van Ness Boynton and Joseph Medill, both supporters of Bristow’s bid for the Republican presidential nomination, warned Blaine of evidence that he had secured a $64,000 loan from the Union Pacific with worthless stock in the Little Rock & Fort Smith railroad.3

Blaine had come to the aid of the troubled Arkansas line as Speaker in 1869 and then became involved with the railroad’s investors. He sold the railroad’s bonds to New England investors for a commission and then received a $160,000 gratuity from the railroad’s backers for his efforts on their behalf.

Accusations of financial involvement with the Union Pacific and its officers remained politically toxic after the Credit Mobilier scandal shook Capitol Hill in the winter of 1872-1873. Railroad mogul Tom Scott, who briefly served as president of the Union Pacific and embodied the sleazy image of railroad speculators and financiers, supposedly approved the loan from the railroad’s coffers with the Arkansas stock serving as its guarantee.

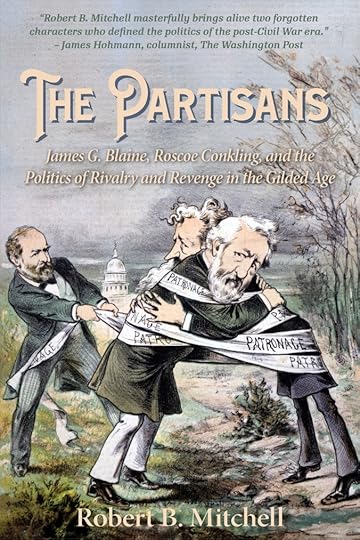

Sen. Roscoe Conkling as rendered in Puck.

Sen. Roscoe Conkling as rendered in Puck.Details of the transaction found their way into the pages of the Democratic Indianapolis Sentinel in April, probably through the agency of either Senator Roscoe Conkling of New York or Senator Oliver P. Morton of Indiana, both rivals of Blaine for the Republican presidential nomination. Blaine believed Conkling — a bitter foe since Blaine mocked the New Yorker’s “turkey gobbler strut” on the House floor a decade earlier — was behind the leak.4

After the story broke in Indianapolis, Blaine responded with a firm denial supported by letters from the Union Pacific and the railroad’s bank. But Democrats sensed they were onto something and directed a House Judiciary subcommittee to look into Blaine’s finances.

Facing heightened scrutiny of his involvement with the Little Rock & Fort Smith, Blaine came to the House floor to offer a more elaborate and impassioned denial that he received funds from the Union Pacific. “I desire here and now to declare that all and every part of this story that connects my name with it is absolutely untrue, without one particle of foundation in fact and without a tittle of evidence to substantiate it,” he declared.

Blaine accused unnamed “emissaries of slander” of pedaling the story to newspapers from Boston to Nebraska and issued a ringing defense of his conduct. “My whole connection with the [Arkansas] railroad has been as open as the day,” he declared. “If there had been anything to conceal about it I should never have touched it. Whenever concealment is desirable, avoidance is advisable, and I do not know any better test to apply to the honor and fairness of a business transaction.”5

A politician who coins a catchy phrase to describe personal ethics better be able to live up to it. Blaine would soon have reason to regret his clever maxim.

In late May, Democrats hit pay dirt with the discovery that the former bookkeeper for Warren Fisher, one of the Arkansas railroad’s investors, kept a sizable collection of correspondence between Fisher and Blaine. The bookkeeper, James Mulligan, came to Washington with the letters and prepared to testify about them before the subcommittee.

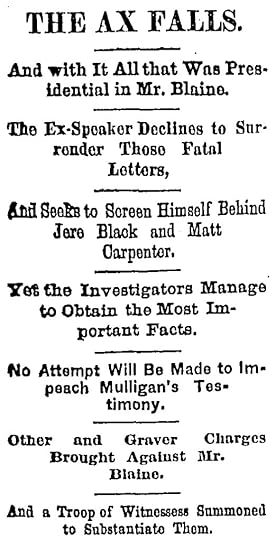

Before he could do so, Blaine met with Fisher and Mulligan to assess their intentions and the contents of the letters. Meeting alone with Mulligan, Blaine asked to look over the correspondence. Mulligan handed him the letters — and then Blaine refused to give them back. After Mulligan testified about the confiscation, Blaine faced the worst crisis of his political career. “THE AX FALLS. And with It All that Was Presidential in Mr. Blaine,” the Chicago Tribune proclaimed.6

With his presidential aspirations — and indeed his career in politics — hanging in the balance, Blaine responded with a daring gambit. He appeared on the House floor with the letters, defended his right to keep them — and then, to the astonishment of the packed chamber, proceeded to read selectively from some of them to prove his innocence.

His colleagues — on both sides of the aisle — considered his speech a tour de force. “It is doubtful whether there has ever been a greater sensation in the House than Mr. Blaine and his case caused,” the Tribune reported the next day. In another story on the speech, the Tribune added:

“Blaine’s speech commenced in almost breathless silence. It ended in an almost a perfect thunder of applause. Blaine has long been noted for the wonderful fertility of his intellectual resources, for his parliamentary skill, and for his audacious bravery. He made use of all his resources today.”7

He may well have carried the day in the House, but the episode strengthened the resolve of his Republican rivals to deny him the party’s presidential nomination. When the party gathered in Cincinnati a week after the dramatic speech, Blaine stood as the frontrunner but could not gain the 379 votes needed for the nomination. On the seventh ballot, Republicans settled on dark-horse Rutherford B. Hayes as their nominee.

Although wounded by the Mulligan letters, Blaine survived. He was elected to the Senate, mounted another unsuccessful bid for president in 1880, and served as secretary of state for President James A. Garfield. In 1884, he finally secured the Republican nomination and would face New York Democratic governor Grover Cleveland in the fall.

But the shadow of the Mulligan letters continued to loom. As the campaign intensified, Mulligan produced more letters from Blaine — including one to Fisher that revealed Blaine had written a letter in 1876 for the investor to issue under his name denying that Blaine was guilty of wrongdoing. The letter closed with cover note that included a damning instruction: “Burn this letter.” Democrats seized on the missive and mocked Blaine by chanting “burn this letter” at rallies.

The Democratic Fort Worth Daily Gazette recast Blaine’s ethical advice from 1876 to twist the knife even deeper. “If his experience was to be gone over again, he would state that apothegm thus: ‘Wherever concealment is desirable, burn your letter before you send it.'”8

The Partisans: James G. Blaine, Roscoe Conkling, and the Politics of Rivalry and Revenge in the Gilded Age will soon be available from Edinborough Press. Other titles by Robert B. Mitchell are available at amazon.com.

The Partisans: James G. Blaine, Roscoe Conkling, and the Politics of Rivalry and Revenge in the Gilded Age will soon be available from Edinborough Press. Other titles by Robert B. Mitchell are available at amazon.com.  Congress and the King of Frauds: Corruption and the Credit Mobilier Scandal at the Dawn of the Gilded Age

Congress and the King of Frauds: Corruption and the Credit Mobilier Scandal at the Dawn of the Gilded Age Skirmisher: The Life, Times, and Political Career of James B. Weaver.St. Cloud Journal, Feb. 10, 1876, p. 2.

Skirmisher: The Life, Times, and Political Career of James B. Weaver.St. Cloud Journal, Feb. 10, 1876, p. 2.  ︎Ron Chernow, Grant (New York: Penguin Books), pp, 796-809; H.W. Brands, The Man Who Saved the Union: Ulysses S. Grant in War and Peace (New York, London, Toronto, Sydney, Auckland: Doubleday, 2012), p. 561.

︎Ron Chernow, Grant (New York: Penguin Books), pp, 796-809; H.W. Brands, The Man Who Saved the Union: Ulysses S. Grant in War and Peace (New York, London, Toronto, Sydney, Auckland: Doubleday, 2012), p. 561.  ︎Donald R. Ritchie, Press Gallery: Congress and the Washington Correspondents (Cambridge,

︎Donald R. Ritchie, Press Gallery: Congress and the Washington Correspondents (Cambridge,Mass., and London: Harvard University Press, 1991), p. 140.

︎Michael Holt By One Vote: The Disputed Presidential Election of 1876 (University Press of Kansas, 2008), p. 75; Allan Peskin, Garfield (Kent, Ohio: The Kent State University Press, 1978, 1999), pp. 398-399.

︎Michael Holt By One Vote: The Disputed Presidential Election of 1876 (University Press of Kansas, 2008), p. 75; Allan Peskin, Garfield (Kent, Ohio: The Kent State University Press, 1978, 1999), pp. 398-399.  ︎U.S. Congress, House, Congressional Record, 44th Congress, April 24, 1876, pp. 2,725.

︎U.S. Congress, House, Congressional Record, 44th Congress, April 24, 1876, pp. 2,725.  ︎Chicago Tribune, June 3, 1876, p. 6.

︎Chicago Tribune, June 3, 1876, p. 6.  ︎Ibid., June 7, 1876, p. 2.

︎Ibid., June 7, 1876, p. 2.  ︎Fort Worth Daily Gazette, Sept. 29, 1884, p. 4.

︎Fort Worth Daily Gazette, Sept. 29, 1884, p. 4.  ︎SearchSearch

︎SearchSearch