The Glass Bead Game

The Glass Bead Game by Hermann Hesse

The Glass Bead Game by Hermann HesseMy rating: 5 of 5 stars

In this review, I share my thoughts on two spectra within the rainbow of knowledge the novel's main character, Knecht, lives: (i) According to Knecht, "one who has experienced the [esoteric] meaning of the Game within himself would by that fact, no longer be a player; he would no longer dwell in the world of multiplicity." I reveal how that is so. (ii) I also unveil a way of knowing and being in the world that Hesse learned of from his spiritual teacher, the naturmensch, pacifist, poet, painter, and antiwar activist Gustav (Gusto) Gräser.

William Wordsworth

As literary critics Harold Bloom and Lionel Trilling wrote, "Before Wordsworth, [English] poetry had a subject. After Wordsworth, its prevalent subject was the poet's own subjectivity . . . and so a new poetry was born."

The core of the subjectivity that Lake Poet William Wordsworth wrote of is a luminous, tranquil transcendental realm, a kind of terra incognita of the spirit, which beckons from within. For when breathing stills, we abide as the calm, shoreless being of our Soul.

Wordsworth:

It is a beauteous evening, calm and free,

The holy time is quiet as a Nun

Breathless with adoration; the broad sun

Is sinking down in its tranquility;

The gentleness of heaven broods o'er the Sea;

Listen! the mighty Being is awake,

And doth with his eternal motion make

A sound like thunder—everlastingly.

Dear child! dear Girl! that walkest with me here,

If thou appear untouched by solemn thought,

Thy nature is not therefore less divine:

Thou liest in Abraham's bosom all the year;

And worshipp'st at the Temple's inner shrine,

God being with thee when we know it not.

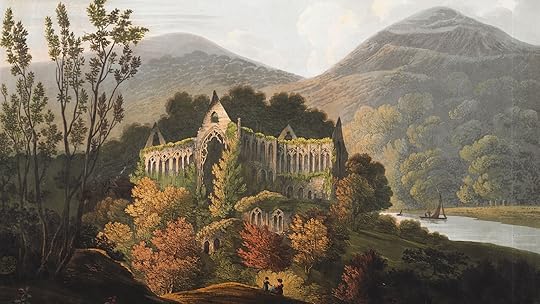

Tintern Abbey

Similarly, in "Lines Written a Few Miles above Tintern Abbey," Wordsworth whispers to us of the power of the same pause between inhalation and exhalation.

Five years have passed; five summers, with the length

Of five long winters! and again I hear

These waters, rolling from their mountain-springs

With a soft inland murmur. –Once again

Do I behold these steep and lofty cliffs,

That on a wild secluded scene impress

Thoughts of more deep seclusion; and connect

The landscape with the quiet of the sky.

The day is come when I again repose

Here, under this dark sycamore, and view

These plots of cottage-ground, these orchard-tufts,

Which at this season, with their unripe fruits,

Are clad in one green hue, and lost themselves

'Mid groves and copses. Once again I see

These hedge-rows, hardly hedge-rows, little lines

Of sportive wood run wild: these pastoral farms,

Green to the very door; and wreaths of smoke

Sent up, in silence, from among the trees!

With some uncertain notice, as might seem

Of vagrant dwellers in the houseless woods,

Or of some Hermit's cave, where by his fire

The Hermit sits alone.

These beauteous forms,

Through a long absence, have not been to me

As is a landscape to a blind man's eye:

But oft, in lonely rooms, and 'mid the din

Of towns and cities, I have owed to them,

In hours of weariness, sensations sweet,

Felt in the blood, and felt along the heart;

And passing even into my purer mind

With tranquil restoration: – feelings too

Of unremembered pleasure: such, perhaps,

As have no slight or trivial influence

On that best portion of a good man's life,

His little, nameless, unremembered, acts

Of kindness and of love. Nor less, I trust,

To them I may have owed another gift,

Of aspect more sublime; that blessed mood,

In which the burthen of the mystery,

In which the heavy and the weary weight

Of all this unintelligible world,

Is lightened: –that serene and blessed mood,

In which the affections gently lead us on, –

Until, the breath of this corporeal frame

And even the motion of our human blood

Almost suspended, we are laid asleep

In body, and become a living soul:

While with an eye made quiet by the power

Of harmony, and the deep power of joy,

We see into the life of things. . . .

Now, as cautiously as a cat approaching its prey, we will slowly advance one silent paw ahead: in the form of a puzzle:

The first part of the puzzle is this: Why does, at first glance, a line in Richard and Clara Winston’s English translation (first published in 1969) of Hermann Hesse’s Das Glasperlenspiel seem to differ so boldly from Hesse's own writing about the esoteric dimension of the Game?

Quoting from the Winston translation:

Perhaps this is the place to cite that other passage from Knecht's letters, which also deals with the Glass Bead Game, although the letter in question addressed to the Music Master, was written at least a year or two later. "I imagine," Knecht wrote to his patron, "that one can be an excellent Glass Bead Game player, even a virtuoso, and perhaps even a thoroughly competent Magister Ludi, without having any inkling of the real mystery of the game and its ultimate meaning. It might even be that one who does guess or know the truth might prove a danger to the Game, were he to become a specialist in the Game, a Game leader. For the dark interior, the esoterics of the Game, points down into the One and All, into those depths where the eternal Atman eternally breathes in and out, sufficient unto itself. One who has experienced the meaning of the Game within himself would by that fact, no longer be a player; he would no longer dwell in the world of multiplicity and would no longer be able to delight in invention, construction, and combination, since he would enjoy altogether different joys and raptures. Because I think I have come close to the meaning of the Glass Bead Game, it will be better for me and for others if I do not make the game my profession, but instead shift to music."

In our exploration of the mystical pause in breathing, advancing another paw forward, I wish to draw attention to this one sentence: "For the dark interior, the esoterics of the Game, points down into the One and All, into those depths where the eternal Atman eternally breathes in and out, sufficient unto itself."

Hesse's original reads as follows: "Denn die Innenseite, die Esoterik des Spiels, zielt wie alle Esoterik ins Ein und All hinab, in die Tiefen, wo nur noch der ewige Atem im ewigen Ein und Aus sich selbst genügend waltet."

If readers do not know German but have sunk their claws into Hesse's sentence, they may think that the word Atem (breath, spirit) is German for the Sanskrit word Atman (Self, Soul, Spirit).

The reader would be both wrong and yet closer to the esoteric secret of the Game, for in the German language, the relationship between breath and Soul is both innate (indwelling) and intimate. Thus, one needs only see that fact nakedly.

Mervyn Savill's 1949 English translation of the line reads as follows: " . . . for the inner meaning, the esoteric of the Game, aims as all esotericism does, deep down into the One and All, where only the eternal In and Out breathing reigns in self-sufficiency."

Readers may have noticed that Savill's translation does not invoke the Sanskrit word Atman, which was also not in Hesse's original.

By including the word Atman, however, Richard and Clara Winston's translation is actually closer to Hesse's original.

My reason for saying this is because the German word Atem and the Sanskrit word Atman both derive from their same ancient, Proto-Indo-European root and still resonate with the root's meanings: breath and spirit.

Thus, the German word Atem means both breath and spirit.

There is an Indian scripture, the Vijñāna Bhairava, which speaks of the transcendent relationship between Spirit and Breath. Readers can access the scripture's verse on breathing through the website on my profile

The Power of Love

Germany's industrial revolution was a nightmare. Wise, sensitive souls escaped the cities. By 1920, a bucolic countercultural enclave had become fashionable enough that Bohème Sauvage dispatched a journalist, Marie de Winter, to Switzerland. Her mission was to rub elbows with the “nature people” at Monte Verità. In her own words, to subsist on a diet of berries, grains, and nuts . . . to till in a garden while wearing only a loincloth . . . to climb the face of a huge rock while completely nude and unbelievably — to do so while accompanied by none other than the famous writer Herman Hesse, who had just applied his finishing touches to his latest novel, Demian.

Monte Verità (Mountain of Truth), in Ticino, had become a spiritual, anticolonial colony of artists and naturalists.

It had been cofounded by a group of Hippies avant la letter, including the naturmensch, itinerant teacher, pacifist, poet, painter, and antiwar activist Gustav (Gusto) Gräser: the German equivalent of America’s Bohemian, Beat, and Hippie generations all rolled into one innocently foundational personality. The painting heading this section of the review is his and entitled "The Power of Love." Hesse's journey to the East was to Monte Verità. He had ventured there to learn of Gräser's ways of being in the world.

Decades later, Americans would become absorbed in these ways only somewhat unknowingly, when, tutored by German nature lovers, California Nature Boys such as Gypsy Boots and Eden Ahbez brought organic smoothies, granola, brown rice, vegetarianism, and veganism to American tables.

Hesse learned from his German naturemensch teacher the health benefits and joys of diving into ice-cold lake waters.

[Stay tuned, to be continued]

View all my reviews

Published on September 08, 2024 15:44

•

Tags:

breath, glass-bead-game, goddess, herman-hesse, hesse, hinduism, kashmir, kashmir-shaivism, lakshmanjoo, meditation, non-dual, nondual, shaiva, tantra, the-glass-bead-game, vijnana-bhairava, wordsworth, yoga

No comments have been added yet.