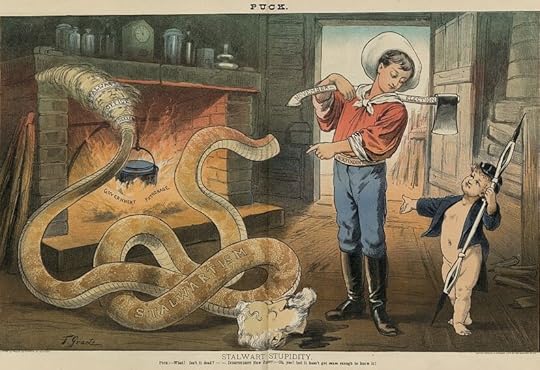

The strange history of ‘Stalwart’

Coined by James G. Blaine, applied to supporters of Roscoe Conkling, and invoked by an assassin.

The tortured political etymology of “Stalwart” originated shortly after Rutherford B. Hayes took office as the nation’s 19th president.

It was April 1877. Washington D.C. was awash in rumors that Hayes had agreed to withdraw federal support for embattled Republican governors in South Carolina and Louisiana as part of a deal with Democrats that allowed him to take office after his bitterly disputed election victory over Democrat Samuel Tilden of New York.

Senator James G. Blaine of Maine, the Republican “Plumed Knight” with a devoted following among the party faithful, warned of the rumored deal and asserted that Hayes could not be a party to it. “I know there has been a great deal said here and there, in the corridors of the Capitol and around and about, in by-places and high places as of late, that some arrangement has been made,” he warned on the Senate floor. “But I deny it on the simple, broad ground that [it] is an impossibility that the administration of President Hayes could do it.”

A month later, when it looked like that was exactly what Hayes was doing, Blaine shared his worries in a letter to the Boston Herald republished April 12 in the New York Times.

Blaine wrote that he fully supported D.H. Chamberlain, the ousted Republican governor of South Carolina. “I am equally sure” that Louisiana’s embattled Stephen Packard “feels that my heart and judgment are both with him in the contest he is still waging against great odds for the Governorship he holds by a title as valid as that which justly and lawfully seated Rutherford B. Hayes in the Presidential chair.”

Blaine continued: “I trust also that both Governors know that the Boston press no more represents the stalwart Republican feeling of New England on the pending issues than the same press did when it demanded enforcement of the Fugitive Slave law in 1851.”

A political label was born.

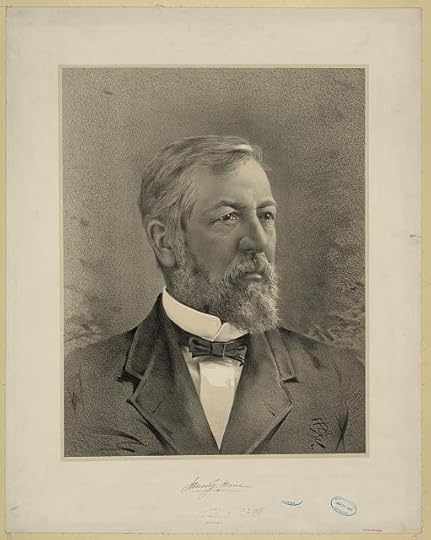

James G. Blaine. Library of Congress.

James G. Blaine. Library of Congress.The letter represented an attempt by Blaine, an astute student of public opinion, to align with rank-and-file Republicans who looked on with alarm at Hayes’s retreat from the vigorous defense of Republican-led Reconstruction state governments.

Hayes was finding all kinds of ways to alienate Republicans, including Blaine’s arch-rival, Senator Roscoe Conkling of New York. Conkling presided over a political machine powered in large part by the patronage bastion at the Port of New York. The port employed around 1,000 workers who owed their jobs and a portion of their paychecks to their political sponsor. President Ulysses S. Grant named allies of Conkling to run the port, giving the senator and his allies control over its vast patronage treasure house.

Hayes styled himself as a reformer who wanted to take patronage out of government hiring practices — and he made Conkling and the Port of New York his top target. The president counted some prominent Republican as allies, including George William Curtis, the editor of Harper’s Weekly who had made civil service reform a personal crusade, and Carl Schurz, the one-time Liberal Republican who now served in Hayes’s Cabinet.

But none were as formidable as Conkling. Imperious, arrogant, and eloquent, the boss of the New York Republican machine would not cower before Hayes and his friends. At the 1877 New York Republican convention, “Lord Roscoe,” as he would become known, angrily proclaimed his contempt for self-styled reformers and their allies in the press, the Cabinet, and White House.

“Who are these men who in newspapers and elsewhere are cracking the whip over Republicans now and playing schoolmaster to the Republican Party and its conscience and convictions?” Conkling thundered as Curtis nervously looked on. “Their vocation and ministry is to lament the sins of other people. Their stock in trade is rancid, flat self-righteousness. They are wolves in sheep’s clothing. Their real object is office and plunder. When Dr. Johnson defined patriotism as the last refuge of a scoundrel, he was unconscious of the then undeveloped capabilities and uses of the word ‘reform.’”

A Stalwart timeline:

April 1877: Blaine uses the phrase “stalwart Republicans” in a letter describing rank-and-file Republican opponents of President Hayes.September 1877: Conkling delivers an angry, eloquent denunciation of civil service reformers at the New York Republican convention in Rochester that makes him the unofficial leader of the stalwart Republicans described by Blaine.1880: “Stalwart” becomes a noun to describe the rank-and-file Republicans loyal to Conkling and other party bosses.July 2, 1881: Assassin Charles Guiteau proclaims “I am a Stalwart” after shooting President James A. Garfield at a Washington train station. Garfield dies of his wound Sept. 19, 1881,Nov. 14, 1881: Blaine testifies at Guiteau’s trial that he “invented” the use of the phrase “stalwart” Republican.Conkling’s furious denunciation of civil service reformers touched a chord with rank-and-file Republicans (not to mention party bosses in other states) and made him — rather than Blaine — the leader of what became known as the Stalwart faction of the Republican Party. By 1880, Blaine carried the banner for a rival faction of Republicans who were less committed to Reconstruction and not as opposed to civil service reform as the Stalwarts. They were known as the Half Breeds.

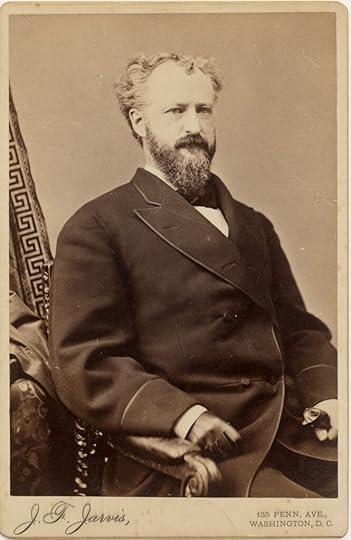

Roscoe Conkling. National Portrait Gallery/Smithsonian Institution.

Roscoe Conkling. National Portrait Gallery/Smithsonian Institution.The feud between Stalwarts and Half Breeds tied the 1880 Republican convention in knots. Stalwarts led by Conkling favored the nomination of Ulysses S. Grant for an unprecedented third term as president. Blaine led the Half Breeds in opposition to Grant and Conkling. It took 36 ballots at the convention in Chicago before Republicans settled on a dark-horse alternative to Blaine or Grant — James A. Garfield of Ohio. To placate New York Stalwarts, Garfield selected Chester A. Arthur, a Conkling ally and former chief of the Port of New York, as his vice-presidential running mate.

Garfield defeated Democratic nominee Winfield Scott Hancock in the fall, but the Stalwart-Half Breed feud persisted. Blaine, Garfield’s secretary of state, cautioned Garfield against giving too much away to Conkling’s Stalwart allies. Conkling wanted his man to run the Port of New York. After weeks of back-and-forth negotiations, Garfield astounded Washington and infuriated Stalwarts by nominating Conkling foe William Robertson to run the port. Conkling and protege Thomas Platt of New York promptly resigned from the Senate, returned to New York, and began campaigning for the state legislature to send them back to Washington.

The feud between Half Breeds and Stalwarts filled the front pages and editorial columns of newspapers. A delusional office-seeker named Charles Guiteau closely followed the drama. As he pursued a longshot campaign for a diplomatic posting, Guiteau became obsessed with the feud and fearful of Blaine’s influence over Garfield. He decided to kill Garfield after concluding that he was the reason he wasn’t getting the diplomatic job he wanted. On July 2, 1881, Guiteau shot Garfield at a Washington train station and then proclaimed, “Arthur is president, and I am a Stalwart.”

Garfield succumbed to his wounds less than three months later. Conkling and Platt failed in their bid to return to Washington. Arthur, now president, surprised Conkling by refusing to remove Robertson at the Port of New York. Guiteau went on trial for the assassination of Garfield on Nov. 14, 1881.

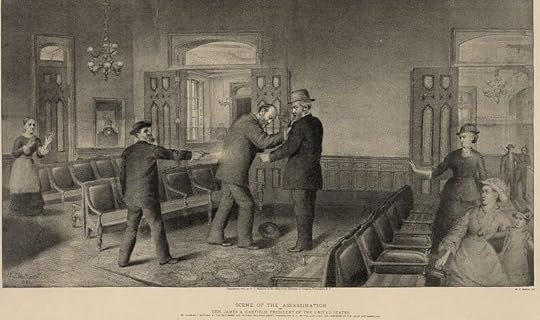

Drawing of the July 2, 1881 shooting of President Garfield (center) by Charles Guiteau (left). Blaine is seen standing next to Garfield. Library of Congress.

Drawing of the July 2, 1881 shooting of President Garfield (center) by Charles Guiteau (left). Blaine is seen standing next to Garfield. Library of Congress.Blaine was the first witness. Under cross-examination by Guiteau’s attorneys, he reprised the battle between Stalwarts and Half Breeds. Blaine was clearly in no mood to dwell on the political feud, and when the topic of the word “Stalwart” came up, he grew irritable. “If counsel is wishing a chapter of political history to form part of the testimony, it ought to be a correct one,” Blaine snapped. “Stalwart” had been in use as a political label long before the Chicago convention, he told the court, “and I invented it myself.”

************

I am finishing a book about the feud between Blaine and Conkling titled The Partisans: James G. Blaine, Roscoe Conkling, and the Politics of Rivalry and Revenge in the Gilded Age. Other books now available at amazon.com:

Congress and the King of Frauds: Corruption and the Credit Mobilier Scandal at the Dawn of the Gilded Age.

Congress and the King of Frauds: Corruption and the Credit Mobilier Scandal at the Dawn of the Gilded Age.

Skirmisher: The Life, Times, and Political Career of James B. Weaver.