From “sic semper tyrannis” to “I am a Stalwart”

John Wilkes Booth, Charles Guiteau, and the madness of assassination.

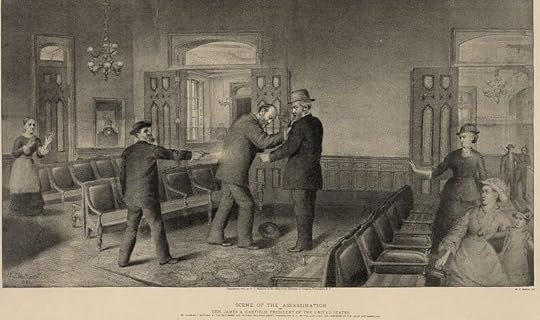

An artist’s rendering of the shooting of James A. Garfield on July 2, 1881. Library of Congress.

An artist’s rendering of the shooting of James A. Garfield on July 2, 1881. Library of Congress.At first glance, the killers of Abraham Lincoln and James A. Garfield would seem to have little in common.

In the early 1860s, John Wilkes Booth appeared to be the latest in his family’s line of talented actors. His father was an accomplished performer, and his older brother, Edwin, was described at his death as “America’s great tragedian.” In 1862, the Chicago Tribune praised the Booth family’s contributions to American theater and foresaw great things for Edwin’s brother. John Wilkes “steps forward to claim the attention of the American public” with talent “equaling both father and brother in the delineation of Shakespearean characters,” the Tribune predicted.1

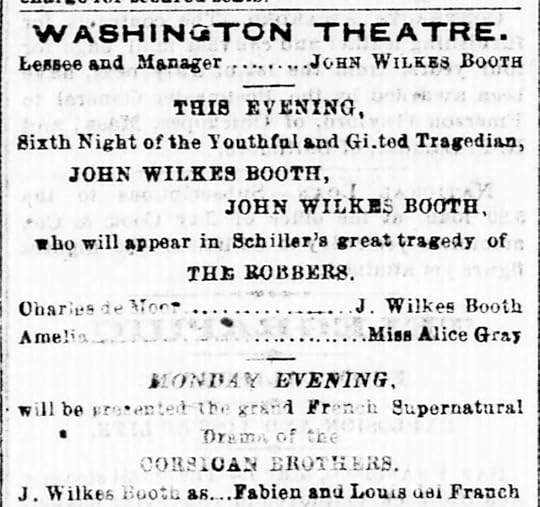

A front-page advertisement for a performance by John Wilkes Booth in the Washington Evening Star, May 2, 1863.

A front-page advertisement for a performance by John Wilkes Booth in the Washington Evening Star, May 2, 1863.Charles Guiteau, on the other hand, was a failed attorney who wrote and sold religious tracts and insurance. The Illinois native joined a New York commune that practiced free love but departed when he was restricted to menial kitchen duty. He beat his wife during their five years of marriage — only one example of his vicious temper. In New York City, he stalked a young woman he believed wrongly to be an heiress until the police told him to stop.2

Booth basked in national acclaim. Guiteau labored in well-deserved obscurity. But both saw themselves as heroes, and today they are joined in infamy for deciding it was their duty to murder a president.

Both believed they would change history. They did – but not in the ways they intended.

On April 14, 1865, less than a week after Robert E. Lee surrendered at Appomattox, Booth fatally shot President Abraham Lincoln at Ford’s Theater. Jumping onto the stage from the presidential box, he shouted “sic semper tyrannis” — the Latin motto of Virginia meaning “thus only to tyrants.” Elsewhere in the capital, an assassin working with Booth gained entrance at the home of Secretary of State William Seward — bedridden as he recovered from a recent carriage accident — and attempted to kill him. Seward and his son suffered serious stab wounds in the attack but survived.

A diehard supporter of the Confederacy, Booth had plotted to kidnap Lincoln in March 1865, apparently in the belief that such an act could turn the tide of the war in favor of the South. That plot fell through, as James L. Swanson recounts in Manhunt: The 12-Day Chase for Lincoln’s Killer, but soon gave way to something more despicable. Instead of kidnapping Lincoln, Booth would assassinate him.3

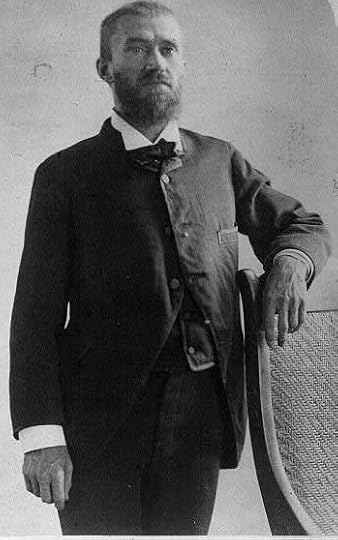

Undated photo of John Wilkes Booth. Library of Congress.

Undated photo of John Wilkes Booth. Library of Congress.Booth hated the idea that once-enslaved Black men and women would enjoy civil and political rights in post-war America. He hoped that killing the president would somehow revive the rebellion, restore enslavement, and consign Lincoln to the dustbin of history. None of those events occurred, Swanson notes. In fact, the shooting transformed Lincoln into a national hero on a par with George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and other honored figures from our past.4

Above all else, Booth wanted to be a hero. But as the New York Herald reported days after the assassination, he failed in all respects.

The assassination of Lincoln and the attempt to kill Seward “continue to inform the engrossing and melancholy subject of thought, feeling, conversation and action throughout the North,” the Herald reported on April 18. “The murder of a Chief Magistrate being an unprecedented event in our history, of course the demonstration of feeling is such as never been before manifested by the people, whose affection for their martyred president, estimation of their great loss, and terrible indignation over the foul act by which his death was produced are unmistakably shown in a nation spontaneously draping itself in the solemn weeds of mourning.”5

While the murder of Lincoln originated in the fevered brain of a diehard Confederate sympathizer, Garfield’s assassination grew out of the delusions of a disappointed office-seeker as a struggle over patronage and power roiled the Republican Party.

Guiteau numbered among the thousands seeking appointment to a job in the Garfield administration. He considered himself worthy of a prestigious diplomataic appointment and pressed his claim at the White House and State Department. At at one point actually gained admission to see Garfield, handing him a copy of a speech he wrote with the words “Paris consulate” scrawled across the top.

Far more significant than Guiteau’s troubles getting a job was the battle for patronage and influence in the new administration being fought by Blaine and Senator Roscoe Conkling, the imperious boss of the New York Republican Party and Blaine’s enemy. Conkling was the titular head of a party faction known as the Stalwarts that included Garfield’s vice president, Chester A. Arthur.

After weeks of trying to propitiate the rival Republicans, Garfield nominated a Conkling foe to run the Port of New York, the patronage bastion that formed the basis of Conkling’s power in the Empire State. Blaine won the power struggle with his archrival.

An undated photo of Charles Guiteau. Library of Congress.

An undated photo of Charles Guiteau. Library of Congress.In protest, Conkling shocked the nation on May 16 when he and his fellow New York Republican Thomas C. Platt resigned from the Senate. His friends in the press hailed the resignations as a triumph of principle over politics. “There are two men in the country, at least, to whom self-respect is more important than office,” the Chicago Inter-Ocean thundered. “Senator Conkling and his colleague have exercised an undoubted privilege and taken a manly course, and have done that which few public men would dare to do in the face of an angry and powerful executive.”6

Many others were critical. “The news produced a profound sensation throughout the country,” the New York Tribune reported. The anti-Conkling Tribune noted that the “conduct of the ex-senators was sharply condemned in Washington and elsewhere.”7

Meanwhile, Guiteau was getting nowhere. He continued his pursuit of a diplomatic position but was eventually barred from the White House. An exasperated Blaine told Guiteau to stop pestering him.8

Following the battle between Blaine, Conkling and Garfield in the newspapers, Guiteau decided God wanted him to kill Garfield to save the Republican Party.

After spending weeks planning the assassination and stalking the president, he fired three bullets into Garfield at a Washington train station on July 2, 1881. Afterward, he tried to cast his murderous attack as an act of altruism. “I did it, and will go to jail for it. Arthur is president, and I am a Stalwart,” Guiteau declared as he was led away by police.9

But Guiteau’s declaration proved premature and wildly off the mark. Garfield clung to life until September 19, when he died in Elberon, N.J. By that time, the political repercussions of Guiteau’s act of madness had claimed Conkling — the leader of the Republican faction on whose behalf Guiteau claimed to be acting — as an unintended victim of the shooting. Conkling failed to win re-election to the Senate, a defeat that ended his career in politics.

Shortly after Garfield was shot, the influential Springfield Republican weighed in from western Massachusetts with a verdict that Conkling and his allies proved unable to overcome. The newspaper described Guiteau as “a miserable ne’er-do-well” who is “in sympathy with Arthur and Conkling in the struggle over the New York custom house.”10

Far from aiding Stalwarts, Guiteau saddled them with the stigma of Garfield’s assassination and accelerated their demise as a dominant force in Republican politics.

****

The assassination of Garfield figures prominently in my upcoming book, The Partisans: James G. Blaine, Roscoe Conkling, and the Politics of Rivalry and Revenge in the Gilded Age. Coming soon from Edinborough Press.

New York Times, June 7, 1893, p. 5; Sacramento Record-Union, June 7, 1893, p. 1; Chicago Tribune, Jan. 17, 1862, p. 4.

New York Times, June 7, 1893, p. 5; Sacramento Record-Union, June 7, 1893, p. 1; Chicago Tribune, Jan. 17, 1862, p. 4.  ︎Kenneth D. Ackerman, Dark Horse: The Surprising Election and Political Murder of James A. Garfield (New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, 2003), p. 135; Candice Millar, Destiny of the Republic: A Tale of Madness, Medicine and the Murder of a President (New York: Anchor Books, 2012), pp. 63-64; George W. Walling, Recollections of a New York Chief of Police (New York: Caxton Book Concern Ltd., 1887), pp. 504-505.

︎Kenneth D. Ackerman, Dark Horse: The Surprising Election and Political Murder of James A. Garfield (New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, 2003), p. 135; Candice Millar, Destiny of the Republic: A Tale of Madness, Medicine and the Murder of a President (New York: Anchor Books, 2012), pp. 63-64; George W. Walling, Recollections of a New York Chief of Police (New York: Caxton Book Concern Ltd., 1887), pp. 504-505.  ︎James . Swanson, Manhunt: The 12-Day Chase for Lincoln’s Killers (Boston, New York: Mariner Books, 2006), pp. 25-26.

︎James . Swanson, Manhunt: The 12-Day Chase for Lincoln’s Killers (Boston, New York: Mariner Books, 2006), pp. 25-26.  ︎Ibid., pp. 386-387.

︎Ibid., pp. 386-387.  ︎New York Herald, April 18, 1865, p 4.

︎New York Herald, April 18, 1865, p 4.  ︎Chicago Inter-Ocean in the Washington Evening Star, May 17, 1881, p. 1.

︎Chicago Inter-Ocean in the Washington Evening Star, May 17, 1881, p. 1.  ︎New York Tribune, May 17, 1881, p. 1.

︎New York Tribune, May 17, 1881, p. 1.  ︎Ibid., p. 121.

︎Ibid., p. 121.  ︎Springfield Republican in New York Times, July 3, 1881, p. 6.

︎Springfield Republican in New York Times, July 3, 1881, p. 6.  ︎

︎