Blaine’s biographer

One of James G. Blaine’s most influential biographers was a member of his extended family and a leading Gilded Age journalist.

Family, friends, and colleagues knew her as Mary Abigail Dodge, or more simply, Abby. The public knew her as Gail Hamilton.1

Gail Hamilton. Wikimedia Commons.

Gail Hamilton. Wikimedia Commons.In an era when women were discouraged from pursuing careers outside the home, and in a profession dominated by cigar-chomping, hard-drinking men, Dodge — who adopted “Gail Hamilton” as her pen name — carved out a unique role as a Washington correspondent whose columns filled the pages of the New York Tribune and other publications.

Born in Hamilton Mass., in 1833, Dodge was a prolific author and editor who began her career in the 1850s writing for the abolitionist National Era in Washington D.C. One of her friends and colleagues was Sara Jane Lippincott, who wrote under the pen name Grace Greenwood for the New York Times. Dodge also happened to be part of the extended family of James G. Blaine. It was through this connection that she produced what is arguably the most revealing — and also the most frustrating — biography of the distinguished Republican elder statesman.2

A former House Speaker, senator, and two-time secretary of state (for James A. Garfield and Benjamin Harrison), Blaine was one of the most popular — and widely disliked — politicians of his generation. Blaine “was born to be loved or hated,” Massachusetts Republican George Frisbie Hoar wrote. “Nobody occupied a middle ground as to him.”3

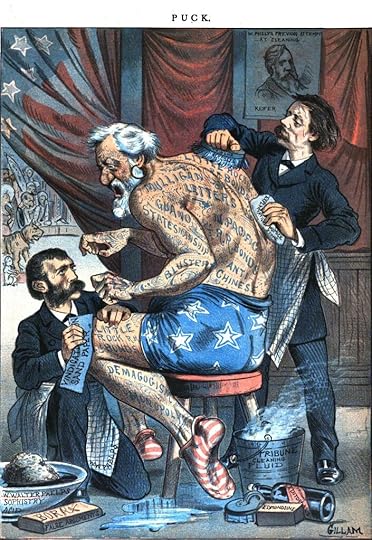

Supporters of James G. Blaine attempt to wash away the stain of scandal on the “tattooed man.” Puck, May 7, 1884.

Supporters of James G. Blaine attempt to wash away the stain of scandal on the “tattooed man.” Puck, May 7, 1884.After Blaine’s death in 1893, authors rushed out biographies of the man known to his devotees as the “Plumed Knight” and to his foes as the “tattooed man” — a reference to a Puck cartoon of Blaine covered in tattoos listing the various scandals with which he was associated. The bibliography accompanying Blaine’s entry in the Biographical Directory of the United States Congress lists no fewer than seven biographies published between Blaine’s death in 1893 and 1934, when David Muzzey published his authoritative James G. Blaine: A Political Idol of Other Days.4 In 2023, Neil Rolde added to the Blaine canon with Continental Liar from the State of Maine.

Some of the biographies attempt to come to grips with Blaine’s controversial career. Charles Edward Russell, a turn of the century muckraker, concedes Blaine’s brilliance as a politician while going into great detail about his ethical shortcomings. Muzzey takes a more balanced approach but also grapples with Blaine’s failings.

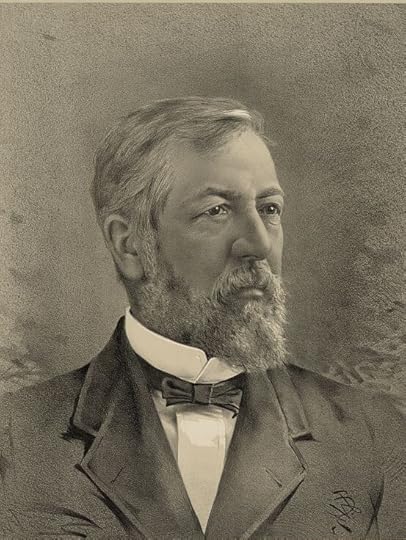

James G. Blaine. Library of Congress.

James G. Blaine. Library of Congress.There is very little objectivity — and certainly none of the scathing commentary of Russell — in Dodge’s James G. Blaine, published in 1895 under the Gail Hamilton pen name. Dodge, who died in 1896, was an unabashed admirer, and her tome is a worshipful account of Blaine’s life and political career.

“Gail Hamilton was the person of all persons to write the life story of Blaine,” according to a review in the Omaha World-Herald. “She had the literary ability, political knowledge, and the necessary personal acquaintance with the great political leader to make the biography intensely interesting. She also had that unbounded admiration and enthusiasm for Blaine which places her in the closest sympathy, not only with him and his career, but with the American public, with whom Blaine holds a place of tender regard rarely equalled.”5

Parsed carefully, this assessment reveals the value and weaknesses of Dodge’s book. The “necessary personal acquaintance” included spending winters with the Blaines in Washington D.C., allowing her glimpses of personalities and events.6 She knew her subject well and, perhaps more than any other biographer, could provide insights into his character and motivations. She also had access to the prolific correspondence of Blaine and, just as importantly, his wife, Harriet Stanwood Blaine, like her husband an acute observer of events and people.

On the other hand, her “unbounded admiration” makes her a less than reliable evaluator of Blaine’s career. Her target audience were those who regarded Blaine with the same admiration as the World-Herald. Less a biographer than a hagiographer, Dodge was uncritically supportive of Blaine’s decisions and motivations. That makes for a tedious read.

Nevertheless, some passages are revelatory. As a student of the Credit Mobilier affair, I was particularly intrigued by her description of Blaine’s behind-the-scenes role as a counselor and adviser to some of the Republicans implicated in the scandal.

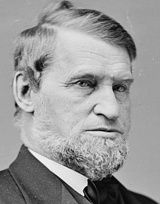

Oakes Ames. Library of Congress.

Oakes Ames. Library of Congress.“Mr. Blaine was indefatigable in defending and advising those who were the objects of attack,” Dodge wrote. Befuddled lawmakers, “gentle and scholarly men, in the natural timidity of their unwontedness, suffered many a pang, and the door-bell sometimes rang Mr. Blaine from his bed at midnight to counsel and console.”7

Oakes Ames, the Union Pacific railroad financier and Massachusetts Republican congressman at the center of the scandal, presented a particularly pitiful sight. One evening, Ames sat before the fireplace in Blaine’s library, “stunned into immobility,” according to Dodge, “with his head bowed on his breast,” while Blaine “applied himself indefatigably in and out of the house, arranging for [Ames’s] defense and for that of the other men who were implicated with him and were equally guiltless of bribery.”8

Dodge was not a neutral observer. Few thought then (or believe today) that the lawmakers implicated in the scandal were entirely “guiltless.” But her observations about Blaine’s behind-the-scenes efforts on their behalf and Ames’s dejected demeanor offer a revealing glimpse into what was going beyond the confines of the Capitol hearing room where the affair was being investigated.

Dodge’s biography is full of similar nuggets. Plowing through it can be tedious, but for students of the Plumed Knight, it is worth it.

****

My book on Blaine’s two-decade long battle with Roscoe Conkling — The Partisans: James G. Blaine, Roscoe Conkling, and the Politics of Rivalry and Revenge in the Gilded Age is coming soon from Edinborough Press.

Susan Coultrap-McQuin, “Gail Hamilton,” Legacy, Vol. 4 (1987), p. 53.

Susan Coultrap-McQuin, “Gail Hamilton,” Legacy, Vol. 4 (1987), p. 53.  ︎Ibid., pp. 54-55.

︎Ibid., pp. 54-55.  ︎George Frisbie Hoar, Autobiography of Seventy Years Vol. 1 (New York: Charles Scribner’s Son,

︎George Frisbie Hoar, Autobiography of Seventy Years Vol. 1 (New York: Charles Scribner’s Son,1903), p. 200. Hereafter referred to as Coultrap-McQuin.

︎The Blaine bibliography lists reprint dates for Muzzey’s book.

︎The Blaine bibliography lists reprint dates for Muzzey’s book. ︎Omaha World-Herald, Aug. 19, 1895, p. 4.

︎Omaha World-Herald, Aug. 19, 1895, p. 4.  ︎Coultrap-McQuin, p. 55.

︎Coultrap-McQuin, p. 55.  ︎Gail Hamilton, Biography of James G. Blaine (Norwich, Conn., Henry Bill Publishing Co., 1895) pp. 285-286.

︎Gail Hamilton, Biography of James G. Blaine (Norwich, Conn., Henry Bill Publishing Co., 1895) pp. 285-286.  ︎Ibid., p. 286.

︎Ibid., p. 286.  ︎

︎