THEY SAID IT COULDN’T BE DONE

There’s no shortage of great quotes in medicine but this one is among my favourites.

“Once they said it could not be done, it was a sufficient challenge to do it.“

Born on this day in 1918, American heart surgeon Walton Lillehei rose to that challenge and pioneered new ways of doing what couldn’t be done.

Clarence Walton Lillehei (1918 – 1999)

Clarence Walton Lillehei (1918 – 1999)Some had said it shouldn’t even be attempted. Operating on the heart was too dangerous. Surgery requires a still and bloodless field. But the heart is in continuous motion, pumping 5 litres of blood every minute. If you stop it, there are dire effects on the brain. It can’t survive more than four minutes without a supply of blood.

In Minnesota, Walt Lillehei came up with the idea of operating on children’s hearts using cross-circulation, where one of the parents does the work of the child’s heart and lungs during the operation. His first patient in 1954 was Gregory Glidden, a thirteen-month-old with a hole in the heart called a ventricular septal defect (VSD). Gregory’s father had the same blood group, so he lay on another operating table next to his child and provided oxygen-rich blood during the surgery.

Gregory’s heart was still beating, but it was bloodless as Lillehei stitched up the hole in the heart. The operation took seventeen minutes. Gregory survived his surgery, though sadly he died of pneumonia a few days later.

Lillehei used cross-circulation on many more occasions to correct congenital heart defects. It was the first series of successful open-heart operations.

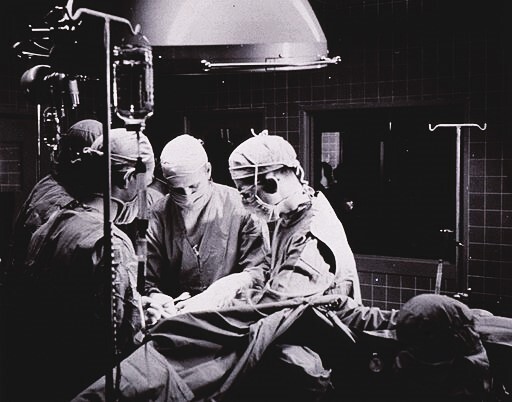

Open-heart surgery in 1955

Open-heart surgery in 1955Reactions were mixed. Some doctors thought his technique was immoral because it put the donor at risk. That was true. The method had, as Lillehei admitted, a potential mortality rate of 200 per cent.

The popular press, on the other hand, was in rapture, especially when one five-year-old girl was riding her tricycle seven weeks after open-heart surgery. A New Heart for Pamela became headline news, never mind that it was a repaired heart rather than a new one.

The publicity had benefits for the blood bank too. Each operation needed about 7 litres of blood, and local residents soon flocked to become donors and help save young lives.

Plastic didn’t come into use for blood bottles until the 1970s

Plastic didn’t come into use for blood bottles until the 1970sOf course, cross-circulation wasn’t always feasible. Lillehei also worked with colleagues to refine the heart-lung machine, a new device that could take over the work of the patient’s heart and lungs during surgery.

Walt Lillehei is just one of the many shining lights that made the impossible possible. There are more trailblazers and their iconic inventions in my newest book The History of Medicine in Twelve Objects.

“Sometimes gruesome, frequently fascinating, and on occasions very funny indeed”, says the Daily Mail.

By a happy coincidence, the book is out tomorrow in hardback, ebook, and audio. You can find out more right here.