Conkling and civil service reform

An outspoken foe of slavery while he served in the House, Roscoe Conkling became preoccupied with patronage and the use of power while in the Senate.

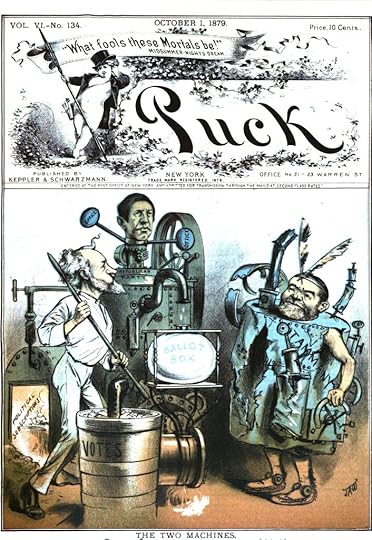

Roscoe Conkling (left) manages the smooth-running Republican machine as a Tammany Hall “brave” wearing a damaged Democratic machine looks on. The cover of Puck, Oct. 1, 1879.

Roscoe Conkling (left) manages the smooth-running Republican machine as a Tammany Hall “brave” wearing a damaged Democratic machine looks on. The cover of Puck, Oct. 1, 1879.Roscoe Conkling personified the hard-headed cynicism of the veteran politician. The Republican senator from New York sneered at reformers and ruthlessly pursued political power to advance the interests of his allies and crush enemies. Barely concealed belligerence enhanced his reputation as an arrogant and vindictive political boss. “Without malignity,” journalist George Alfred Townsend once wrote, “Conkling is nothing.”1

At the New York Republican convention in Rochester in 1877, Conkling blasted civil service reformers as canting hypocrites with one of the most memorable rhetorical broadsides of the Gilded Age:

Who are these men who, in newspapers and elsewhere, are cracking the whip over Republicans now, and playing schoolmaster to the Republican Party, and its conscience and convictions? Some of them are the man-milliners, the dilettanti and carpet-knights of politics; men whose efforts have been expended in denouncing and ridiculing and accusing honest men who, in storm and sunshine, war and peace, have clung to the Republican flag and defended it against those who tried to trail and trample it in the dust. … Some of these worthies masquerade as reformers. Their vocation and ministry is to lament the sins of other people. Their stock in trade is rancid, flat self-righteousness. They are wolves in sheep’s clothing. Their real object is office and plunder. When Dr. Johnson defined patriotism as the last refuge of a scoundrel, he was unconscious of the then undeveloped capabilities and uses of the word ‘reform.’ 2

Conkling’s target was George William Curtis, the editor of Harper’s Weekly and a champion of civil service reform whose magazine had recently begun publishing articles about women’s fashion. But Conkling’s contempt extended to all self-styled reformers, not the least of whom was the President Rutherford B. Hayes.

After winning the Republican presidential nomination in 1876, Hayes made it clear that he would run as a reformer rather than merely the successor to Ulysses S. Grant, whose second term came concluded with a cloud of corruption hanging overhead. At the top of Hayes’s reform agenda was civil service reform and an end to patronage in federal hiring.

Patronage, he asserted, promotes corruption, inefficiency and mismanagement. It hinders the dismissal of incompetent officials and compromises the ability of government employees to devote themselves wholly to the public good. “It ought to be abolished,” Hayes argued. “The reform should be thorough, radical and complete.”3

Sidelined by illness, Conkling — nicknamed “Lord Roscoe” by the press — did not campaign for Hayes that year. But it isn’t difficult to imagine that he wasn’t eager to hit the hustings on behalf of the Republican nominee. Hayes’s position on patronage amounted to a direct attack on the boss of the New York Republican machine.

“When Dr. Johnson defined patriotism as the last refuge of a scoundrel, he was unconscious of the then undeveloped capabilities and uses of the word ‘reform.’“

— Sen. Roscoe Conkling

At the heart of Conkling’s power was a vast patronage empire based at the Port of New York that supplied an army of workers and a steady stream of campaign funds in the form of “assessments” drawn from workers’ pay. Control of the port put Conkling atop the New York Republican political machine and made him a target for self-styled reformers who advocated an end to patronage politics in the federal government.

Hayes made good on his vow to target patronage empires when he nominated Theodore Roosevelt Sr., the father of the future president, to run the Port of New York. Conkling summoned the support of his Republican allies in the Senate to defeat Roosevelt’s nomination. But the battle reinforced Conkling’s reputation as the embodiment of the abuses ascribed to patronage politics.

Campaign poster from 1876 for Republicans Rutherford B. Hayes and vice-presidential candidate William Wheeler. Library of Congress.

Campaign poster from 1876 for Republicans Rutherford B. Hayes and vice-presidential candidate William Wheeler. Library of Congress.The Nation, the leading journal of liberal critics of Grant and his allies, made this abundantly clear in October 1877 as it reacted to Conkling’s speech in Rochester. After the war, the liberal weekly newspaper argued, the Republican Party came to be dominated by a “distinct breed of politicians possessing no real interest in legislation, with but little disposition or capacity for the management of pressing public business, and relying almost wholly for success and prominence on the use of government service in the reward of personal followers.”

Conkling was “an excellent specimen” of the spoilsmen who came to dominate the Republican Party in the years after the war, the Nation editorialized. “As a politician of power and prominence,” the Nation editorialized in 1877, “he is really a compound” of the port’s army of patronage employees. “He is made up of them, and draws his whole sustenance from them.”4

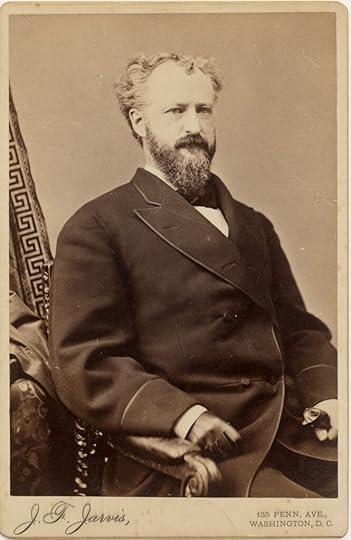

Undated photo of Roscoe Conkling. National Portrait Gallery.

Undated photo of Roscoe Conkling. National Portrait Gallery.Much of this indictment rings true. But it wasn’t always the case.

As a member of the House, Conkling allied himself with radical Republican Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania and belonged to the Joint Committee on Reconstruction that fashioned the Fourteenth Amendment. Before the outbreak of the Civil War, Conkling passionately denounced slavery as a “barbarous and detestable crime.” After the war, as Congress debated how to reconstitute the states of the defeated Confederacy, he proved a forthright champion of enfranchising Black men as he denounced the notorious Constitutional clause allowing slave states to count enslaved people as fractional humans for purposes of congressional apportionment. “If a black man counts at all now, he counts five-fifths of a man, not three-fifths,” Conkling told the House in 1866. “Revolutions have no such fractions in their arithmetic; war and humanity join hands to blot them out.”5

In the House, he distinguished himself as one of the leading and most articulate champions of constitutionally protected Black suffrage. As a senator, it was a different story. Conkling remained a supporter of Black political and civil rights but became more preoccupied with the accumulation and use of political power while Senate radicals like Oliver Morton of Indiana and Charles Sumner of Massachusetts led the fight to reconstruct the political order in the South.

In 1870, Conkling backed Grant’s nomination of Thomas Murphy to run the Port of New York and supplanted Senator Reuben Fenton as the leader of the state Republican organization. When Sumner vocally opposed Grant’s plan to annex Santo Domingo, Conkling led the charge in the Senate against the Massachusetts Republican that led to Sumner’s ouster as chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee.

The installation of Murphy at the Port of New York and Conkling’s assault on Sumner’s Senate standing bonded Grant and Conkling. After scandal forced Murphy to resign in 1871, Conkling’s control of the port’s patronage muscle strengthened with the appointment of his ally, Chester A. Arthur. Conkling’s alliance with Grant grew stronger.

Conkling retained his loyalty to Black Southern Republicans even as he grew more preoccupied with the accumulation and uses of political power. In December 1875, when Black Republican Blanche K. Bruce was sworn in as a new senator from Mississippi, Conkling escorted Bruce to the desk of the Senate clerk to present his credentials while others in the all-white chamber ignored him.

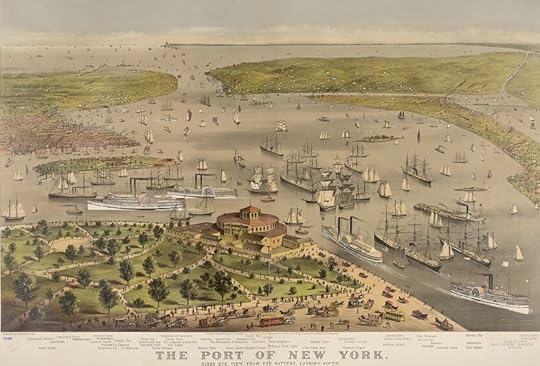

Currier and Ives lithograph of a bird’s eye view of the Port of New York. Library of Congress.

Currier and Ives lithograph of a bird’s eye view of the Port of New York. Library of Congress.But such moments were overshadowed by the struggle for power that consumed Conkling in the years to come. Lord Roscoe fought Hayes to a draw in the battle over control of the port. Hayes eventually replaced Arthur with a Republican acceptable to all party factions. Conkling became the leader of the Republican faction known as the “Stalwarts” for their affinity to Grant and opposition to reformers.

The battle for control of the port resumed with the election of Republican James A. Garfield in 1880. Garfield found himself in the middle of the years-long rivalry between Conkling and Blaine, who pushed for the nomination of Conkling foe William Roberston to run the port.

Garfield dithered for weeks before nominating Robertson. Infuriated, Conkling resigned from the Senate and then decided to campaign for his old job. By this time, Republicans in Albany had lost patience with Conkling, who, out of office, was no longer in a position to compel their support. The shooting of Garfield on July 2, 1881, by a deranged gunman who proclaimed “I am a Stalwart” as he was led away by police, further weakened Conkling’s standing. State legislators elected a successor to Conkling on July 22, 1881, and ended his political career.

Conkling’s decision to leave the Senate over a dispute involving patronage highlighted — as nothing else could — how his priorities shifted after he left the House. He ended his political career in a struggle over what abolitionist Wendell Phillips dismissed as “the loaves and fishes of office” and sealed his reputation as a party boss rather than a statesman.6

—-

Coming next year from Edinborough Press: The Partisans: James G. Blaine, Roscoe Conkling, and the Politics of Rivalry and Revenge in the Gilded Age.

Chicago Tribune, Jan. 31, 1872, p. 2.

Chicago Tribune, Jan. 31, 1872, p. 2.  ︎New York Times, Sept. 27, 1877, p. 2.

︎New York Times, Sept. 27, 1877, p. 2.  ︎Ibid., July 10, 1876, p. 1.

︎Ibid., July 10, 1876, p. 1.  ︎The Nation, Vol. 24-25, October 4, 1877, p. 206.

︎The Nation, Vol. 24-25, October 4, 1877, p. 206.  ︎U.S. Congress, House, Congressional Globe, 36th Congress, 1st session, Appendix, April 17, 1860, p. 233; Ibid., 38th Congress, 2nd session, Jan. 22, 1866, p. 356.

︎U.S. Congress, House, Congressional Globe, 36th Congress, 1st session, Appendix, April 17, 1860, p. 233; Ibid., 38th Congress, 2nd session, Jan. 22, 1866, p. 356.  ︎Wendell Phillips in “Ought the Negro to be Disfranchised? Ought He to Have Been Enfranchised?” North American Review, Vol. 128, No. 268, March 1879, p. 258.

︎Wendell Phillips in “Ought the Negro to be Disfranchised? Ought He to Have Been Enfranchised?” North American Review, Vol. 128, No. 268, March 1879, p. 258.  ︎

︎