The Infamous Ben Lily

I’m in the Silver City area for a few weeks waiting until March 15th when I am speaking at the Tucson Book Fair. Hiking around the Gila National Forest (our first Wilderness thanks to Aldo Leopold), I can’t help but contemplate Ben Lilly.

Ben Lily features prominently in the second chapter of my latest book Ghostwalker: Tracking a Mountain Lion’s Souls through Science and Story. Lily was single-handedly responsible for the deaths of 500 mountain lions, over 600 bears, and the last grizzlies in the Southwest. He was a predator-killing machine epitomizing the hatred for predators in the early 20th century.

Today I took a short hike to what locals call Ben Lilly Pond, a 1/2 mile turn-off from Highway 15 before the Ben Lily Memorial.

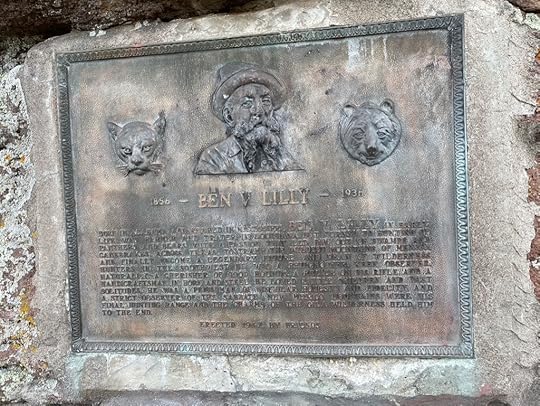

The Ben Lilly Memorial plaque in the Gila National Forest against a large boulder overlook. See the lion and bear on either side

The Ben Lilly Memorial plaque in the Gila National Forest against a large boulder overlook. See the lion and bear on either sideAt the age of forty-five, in 1901, Lilly called his second wife and three children together, kissed them goodbye, and left them everything he owned except five dollars. Leaving his home state of Louisiana, he headed west for a land where the big predators remained. His life philosophy was now well formed. He regarded himself as the policeman of the wild, “a self-appointed leavener of nature.” Bears and lions specifically were, by their very nature, evil. Lilly considered it his biblical duty to set things straight by killing these “devil” animals. He had evolved into a religious fanatic, mixed with a special kind of mysticism. As Lilly traveled west, he left behind a wake of wildlife destruction. But his folk-hero status was growing. While hunting in Texas in 1907, Lilly received a telegram summoning him to a presidential camp on Tensas Bayou for a bear hunt with President Theodore Roosevelt.

1908 Scribner’s article: Theodore Roosevelt “In the Louisiana Canebrakes,” Scribner’s XLIII (January 1908) Courtesy Avery Island Archives, Avery Island, La.

1908 Scribner’s article: Theodore Roosevelt “In the Louisiana Canebrakes,” Scribner’s XLIII (January 1908) Courtesy Avery Island Archives, Avery Island, La.In 1908, Lilly hunted grizzlies, mountain lions, and black bears in Mexico for three years, sending skeletons and skins back to the Smithsonian Institution. He returned to the United States, entering through the boot heel of New Mexico. Now in his mid-fifties, his predator killing career was waxing as a new era of government eradication programs for predators began. His reputation was widespread, his services were in high demand among ranchers, and he was finally well paid for a passion previously pursued only as a personal vendetta.

On the road to Ben Lilly Pond. An old ranch entrance now shot full of bullet holes

On the road to Ben Lilly Pond. An old ranch entrance now shot full of bullet holesWhen trailing with his dogs, Lilly would forget to eat and drink, sometimes for days on end. Then he’d gorge himself on his kill and the bit of corn meal he carried with him. He never kept the skins of the animals he killed for himself, considering them a worthless piece of clothing. He was on a mission, and that intensity of focus molded him into an expert woodsman. He had no coat, but piled on layers of shirts. If he was cold, he’d build a fire, push aside the coals, and sleep on the warm ground. At least once a week he bathed in a stream, sometimes breaking away the ice, then rolling in snow to dry off. The air in a town was toxic to him, and when offered a bed, he preferred to sleep outside on the ground with his dogs.

To the men who knew him, Lilly was a man of complete honesty and character. He never swore, drank, or smoked, and famously rested on Sunday, his holy day. If his dogs treed a cougar on Saturday night, the animal had a stay until Monday morning. But his religious beliefs extended to the supernatural. Lilly’s favorite meats were bear and especially lion, which he felt would endow him with exceptional instinct, prowess, and agility to pursue his quarry. He expected no less of his dogs than he did of himself—running them for days without food. He would go out of his way to make sure they had water before he did, took great pleasure in watching them work, and valued a dog’s intelligence rather than a specific breed. Yet ultimately, they were simply tools of his trade. If a dog began running trash or quit the trail, he had no need for him, and the dog was beaten or shot to death.

Ben Lilly was unquestionably one of the most destructive figures in North American wildlife history, contributing to the demise of the grizzly bear and the wholesale reduction of mountain lions and black bears in the Southwest. The plaque above was erected by friends who knew him, back in the 1930s. But there are some folks today that revere Lily as the ultimate hunter, apparently ignorant of the havoc and destruction he left behind in the Southwest.

The terrain and vegetation of the Gila

The terrain and vegetation of the GilaWalking the jeep road to the pond (which was completely dry), I did have to marvel at how this strange man maneuvered these mountains. The scrubby oaks, pines and junipers are so thick they are almost impossible to pass through. The ground is rocky and the going rough. But I wonder how many people who take these short hikes even know who Lilly was and the devastation he caused to our wildlife.

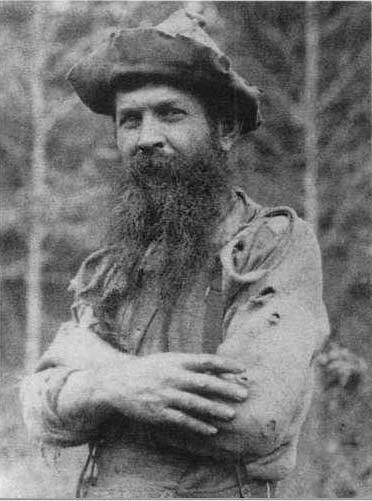

Ben Lilly

Ben LillyLilly’s lack of true reverence for life is the antithesis of our values of ethical hunting and wildlife conservation—a misguided, warped sense of nature that viewed large predators as “endowed by their very nature with a capacity to wreak evil…and should be destroyed.” A misshapen, exaggerated product of his era, one could consider Lilly a vessel—a queer, half-crazed man who performed his executions as a service for others, for the government, and in his own mind, for God. Genocidal war on predators had been codified as our nation’s God-given right, and Lilly was their proxy.

If you are in Tucson on March 15th, come to the Tucson Book Fair. It’s huge with a wide variety of authors and speakers. I’ll be speaking at 10am at the Western National Parks Association Stage