Taxes in The Arthurian Age

So I just finished doing my taxes; that time of year when I get acid-reflux and my wife says I turn from her easy-going teddy bear to an irritable grouch. Sorry, babe. Anyways, it got me thinking about taxes in the Arthurian Age. How were taxes collected and what was done with them?

The Romans had, much like the other aspects of their empire, a methodical system for taxes. There was a census about every five years and this was used to assess a yearly poll tax on each adult, which tended to vary. There was also a tax on the value of land, of around 1% to 3%. Custom duties were collected at borders, bridges and gates, at around 2.5%. Items sold at auction were typically taxed at about 1%, and there was a 5% inheritance tax (usually not charged against close relatives). This is rather generalized, partly because additional taxes might be levied in times of emergency, but also because of how the taxes were collected.

Local aristocrats were appointed by the government to collect the taxes, but these people were not going door to door for the often dirty and always thankless job. Sometimes they appointed tax collecting officials who were paid a salary, but more often, they would offer contracts to private citizens or companies to collect taxes. The contractors, known as “publicani”, would offer to pay all the taxes up front. The highest bidder was given the contract to collect taxes from the population. The publicani made their profit by whatever they could collect above what they had paid to get the contract. Needless to say, graft, extortion, cheating and even violence was not uncommon and tax collectors were often seen as the lowest of vermin within the empire.

Tax revolts were not uncommon in the empire, particularly in the 3rd century, when the Western Roman Empire was in crisis. Insurgents known as bacaudae, made up of peasants, runaway slaves and army deserters, caused as much trouble as barbarian invasions and even caused regions, such as Armorica, to break away from Roman control.

Prior to the Roman occupation, most of Britain operated on a barter system, aside from some southern tribes that used coinage because of their frequent trade with Roman Gaul. Rome’s introduction of a standard currency in Britain made trade easier, as well as tax collection. After the Roman government in Britain collapsed, coins became rare and the Celtic British quickly reverted to their old bartering systems for what little trade remained. It changed how taxes were collected in the Arthurian Age.

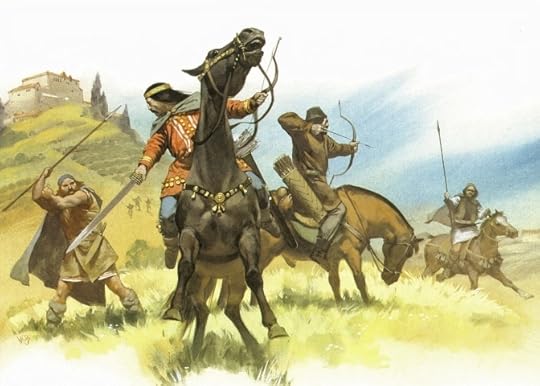

Without a centralized government, local rulers, warlords and petty kings had to fund and feed their warriors and households from their decentralized holdings. It was difficult and often arbitrary to extract food, livestock and goods from peasants who learned to hide the meager returns of their subsistence farming well, or risk starving. Some taxes were collected from trade, but often, the warlord’s best source of wealth came from raiding their neighbors, and this contributed to the endemic warfare which characterized the “Dark Ages”.

As the early Anglo-Saxons became more established in Britain, they brought their own tax system. It was based on the “hide“, which was a unit of land capable of supporting a free peasant family, usually about 120 acres. A tenant family paid their taxes in much the same way as the Britons, until the Anglo-Saxons started using their own coinage in the 7th and 8th centuries. They also had a system of fines for judicial cases that were paid to the king.

In Europe, the nomadic Huns didn’t have a formalized tax system, instead relying on raiding, plunder, and tribute from those they conquered. The Visigoths in Gaul and Hispania collected tribute from their formerly Roman subjects and also assessed land taxes based on the Roman practice.

In my novels, I have some portrayals related to taxes in the Arthurian Age. If you recognize any of them, or having any thoughts on the subject, I’d love to hear from you. Until next time!

The post Taxes in The Arthurian Age appeared first on Sean Poage.