Harry Harrison Centenary – Part 2: The Second World War

Harry Harrison received his draft notice on his eighteenth birthday in March 1943. As he put it, the letter marked the end of his childhood and the beginning of his adult life. He was told to report to Grand Central Palace in Manhattan for a physical examination which would determine whether he was fit enough to join the military. In his memoir, Harrison writes about this experience with grim humour, but it’s clear it was an unpleasant and dehumanising one. “Was this deliberate sadism?” he asks. “Probably not. Just the military’s total indifference to the individual as a thinking, separate human being.”

Certified fit, Harrison was ordered to report to Camp Upton on Long Island. He spent a month there, finding escape in the novels of H.G. Wells and Jules Verne, and then learned he was to join the Army Air Corps. Perhaps it was just luck or perhaps learning about aircraft instruments at night school had paid off. Either way, as he ironically puts it, “I never saw an aircraft instrument again.”

He was sent for basic training to Keesler Field, Biloxi, Mississippi. It was July, ninety degrees Fahrenheit (32°C) and humid. The young soldiers were subjected to intense physical exercise and mental stress to see if they would break. Harry Harrison discovered in himself an instinct for survival and also a streak of stubbornness – he would not let the bastards grind him down. These two things got him through the ordeal with heat rash being his biggest complaint. The physical training that reduced him to “…a 135 pound weakling, had built me back up to a fit, tanned and strong 160 pounds.”

Harry Harrison in military uniform

Harry Harrison in military uniformHe couldn’t become an aircraft pilot because of his eyesight – he’d worn glasses since he was young; but there was a possibility that he could become a glider pilot. When his orders finally came through, Harrison discovered that he was being sent to a ‘secret military school’ at Lowry Field in Denver, Colorado. This was a result of his having scored 156 out of 160 in the Mechanical Aptitude test – “The best score I ever got in my life!” It was almost the end of 1943 when he shipped out.

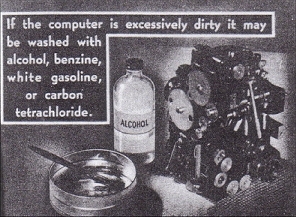

Keep Your Computer Well-GreasedAt Lowry Field, Harry Harrison was trained to operate and maintain a Sperry Mark 3 Computing Gunsight. He described it as “…a lumpish black object with an angled piece of glass on its top that was framed by a metal cage. Nothing about it resembled any device I had ever seen before. I realized with a touch of panic that I had a lot to learn.” And “…the gunsight was mounted in the top of a tub-like revolving turret, ominously close to two gigantic machine guns. There was a complex handgrip and a folding seat for the gunner … With the aid of the computer the gunner aimed and fired the two .50 caliber guns that framed his head.” This was the Power Operated Turret, and the young trainees would also need to become gunsmiths, learning how to service the machine guns.

When we think of computers today, we think of laptop devices with microchips inside. The ‘computing gunsight’ that Harrison worked on was nothing like that. It was an analog computer, not a digital one.

“Gears, rollers, gear trains and ball cages, cams and cam followers and plenty of grease made these remarkable machines function – and function well,” Harrison wrote in an unpublished text on this type of computer.

There are some excellent images of the gunsight computer on the Glenn’s Museum website here. Click on the images to enlarge them.

By the end of Spring 1944, Harrison had finished his training. “I was now the proud owner of a triangular patch with a bomb on it – representing my new ranking as an armaments specialist. I sewed it onto my sleeve.” Officially, he was a Power Operated Turret and Computing Gunsight Specialist – 678. After a year’s experience he could add a three on the end to become 678-3, an indication that he was ‘skilled.’ “Having qualified on a number of weapons during training I also wore a sharpshooter’s medal on my pocket with pendant details: caliber .50, Garand rifle, Riesling submachine gun.”

Harrison was sent to Kelly Field, San Antonio to await his next assignment. That was to Laredo Air Force Base, an aerial gunnery school with an associated gunnery range, in Laredo, Texas, near the Mexican border. This would be his ‘home’ until the end of the war.

The purpose of the base was to train aerial gunners. Harrison was assigned to the ground range where students fired live rounds for the first time. A turret with two caliber .50 guns was mounted to the back of a six-by-six Chevy truck. Initially, it was his job to service and adjust the computing gunsight between the guns. Then he was given the job of servicing the guns as well. And then he took on the role of instructor. He also ended up driving the truck, despite the fact that he’d never driven even a car before – “I almost turned it over!”

The pounding of the massive guns damaged Harrison’s hearing and the food on the base was terrible, but at weekends he was allowed out on a pass and could enjoy the Mexican food and drink. Daily life was monotonous, and he compared it to serving time in prison: you serve one day at a time and look forward to your eventual release. At some point, to relieve the boredom, he attended a lecture about the ‘artificial language’ Esperanto. He picked up a book called Learn Esperanto in 17 Easy Lessons and learned enough to be able to correspond with other Esperantists. He was barely aware of the progress of the war in Europe – until the training base in Laredo was shut down.

Military PoliceHarrison was transferred to another gunnery school – Tyndall Field in Panama City, Florida – but when he got there, their gunnery training was shut down too. His expertise was no longer needed. By this stage, he had achieved the rank of sergeant. The only opening available was in the Military Police.

The other MPs were from south of the Mason Dixon line. As a Yankee from New York, Harrison wasn’t exactly welcome in their ranks. They decided to put him in charge of the stockade that housed black prisoners. The Army was segregated and so were their prisons. Harry was given a shotgun to guard his prisoners, and it was their job to go out in a garbage truck and collect the trash. And to add insult to injury, he also had to eat in the black mess hall. It could have been a nightmare situation, but it turned out to be the exact opposite.

Most of the black prisoners were also from the north. And many of them had ended up in the stockade for talking back to ‘superior’ officers. They just wanted to serve out the rest of their time in the military and get clean discharge. They didn’t cause Harrison any problems. And the cook in the black mess hall had been salad chef at the Waldorf Astoria in New York. He could take the basic ingredients the army provided and turn it into something that, unlike most military meals, was good to eat.

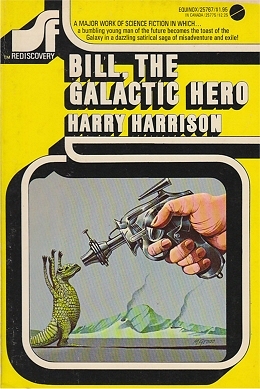

Artwork: Michael Gross

Artwork: Michael GrossIn 1946, Harry Harrison received his discharge and returned to New York as an adult who was “…totally adjusted to military life – and totally unprepared for my future as a civilian.” He took back with him a dislike of the military that stayed with him for the rest of his life. “If you read Bill, the Galactic Hero you’ll see how I feel about the army!” He also claimed to have learned something else from the black soldiers he supervised. “I was the first white person in New York to use the word motherf*cker!”

Next: Cartoonist & Illustrator

Paul Tomlinson is the author of over a dozen novels and books about writing genre fiction. www.paultomlinson.org

Harry Harrison's Blog

- Harry Harrison's profile

- 1036 followers