A self-guided writing workshop: Trees and the Wild

Hello!

Something a bit different from me this week. I thought I’d share one of my writing workshops. This is a shortened version of my workshop all about trees and the wild. So, I invite you this week to block out an hour for yourself. Make a hot drink for yourself and hide yourself away somewhere. It is a self-guided workshop so you can move through the prompts as slowly or quickly as you like.

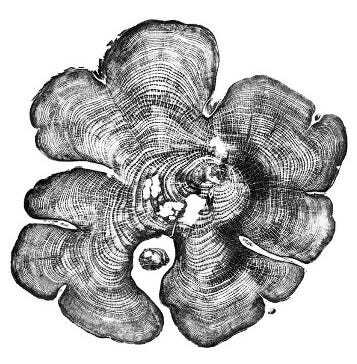

Image: Bryan Nash Gill

Image: Bryan Nash Gill

Image credit: Bored PandaTrees and the Wild: A self-guided workshop

Image credit: Bored PandaTrees and the Wild: A self-guided workshopWelcome to this self-guided writing workshop about trees and the wild. All you need is a pen, notepad and one gift from a tree (could be a branch, leaf or bud).

It is an ideas generation course, so will hopefully after this workshop, you will have a notebook full of starters that might one day turn into something. Don’t worry about the quality of your writing, just write!

Writers often talk about their ideas settling down and composting. You scribble them down and when you return to them weeks, months or years later, they have turned into something valuable, something that you hadn’t seen before.

‘Our bodies are garbage heaps: we collect experience, and from the decomposition of the thrown-out eggshells, spinach leaves, coffee grinds, and old steak bones of our mind come nitrogen, heat and very fertile soil. Out of this fertile soil bloom our poems and stories.’ Nathalie Goldberg

‘I have always kept notebooks – I have an obsessive devotion to them – and I go back to them over and over. They are my compost pile of ideas. Any scrap goes in and after a while I’ll get a handful of earth.’ Louise Erdrich

Image credit: Bored Panda

Image credit: Bored Panda

Image credit: Bored PandaStep One

Image credit: Bored PandaStep One Take your tree gift, it might be a leaf, a twig, a bud.

Look at it, smell it, touch it.

Now read this from Ted Hughes and then freewrite for five minutes. (Don’t stop writing, don’t edit!)

‘The only thing is, imagine what you are writing about. See it and live it. Do not think it up laboriously, as if you were working out mental arithmetic. Just look at it, touch it, smell it, listen to it, turn yourself to it. When you do this, the words look after themselves, like magic. If you do this, you do not have to bother about commas or full-stops or that sort of thing.. The minute you flinch and take your mind off this thing, and begin to look at the words and worry about them.. then your worry goes into them and they set about killing each other.’ Ted Hughes

Miners is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Step TwoRead these quotes about trees and let the words speak to you. Jot down anything that speaks to you.

‘We feel for them [the trees] because we identify with them. Like us, they are small and helpless when they are young. Like us, they take power in their power when they come to maturity. And, like us, they come to a tottering old age when they are once again dependant on others for survival.’

Alexander Van Humboldt

‘For me, trees have always been the most penetrating preachers. I revere them when they live in tribes and families, in forests and groves. And even more I revere them when they stand alone. They are like lonely persons. Not like hermits who have stolen away out of some weakness, but like great, solitary men, like Beethoven and Nietzsche. In their highest boughs the world rustles, their roots rest in infinity; but they do not lose themselves there, they struggle with all the force of their lives for one thing only: to fulfill themselves according to their own laws, to build up their own form, to represent themselves. Nothing is holier, nothing is more exemplary than a beautiful, strong tree. When a tree is cut down and reveals its naked death-wound to the sun, one can read its whole history in the luminous, inscribed disk of its trunk: in the rings of its years, its scars, all the struggle, all the suffering, all the sickness, all the happiness and prosperity stand truly written, the narrow years and the luxurious years, the attacks withstood, the storms endured. And every young farmboy knows that the hardest and noblest wood has the narrowest rings, that high on the mountains and in continuing danger the most indestructible, the strongest, the ideal trees grow.’

‘A tree says: A kernel is hidden in me, a spark, a thought, I am life from eternal life. The attempt and the risk that the eternal mother took with me is unique, unique the form and veins of my skin, unique the smallest play of leaves in my branches and the smallest scar on my bark. I was made to form and reveal the eternal in my smallest special detail.’

‘A tree says: My strength is trust. I know nothing about my fathers, I know nothing about the thousand children that every year spring out of me. I live out the secret of my seed to the very end, and I care for nothing else. I trust that God is in me. I trust that my labor is holy. Out of this trust I live.’

‘When we are stricken and cannot bear our lives any longer, then a tree has something to say to us: Be still! Be still! Look at me! Life is not easy, life is not difficult. Those are childish thoughts. . . Home is neither here nor there. Home is within you, or home is nowhere at all.

A longing to wander tears my heart when I hear trees rustling in the wind at evening. If one listens to them silently for a long time, this longing reveals its kernel, its meaning. It is not so much a matter of escaping from one’s suffering, though it may seem to be so. It is a longing for home, for a memory of the mother, for new metaphors for life. It leads home. Every path leads homeward, every step is birth, every step is death, every grave is mother.’

‘So the tree rustles in the evening, when we stand uneasy before our own childish thoughts: Trees have long thoughts, long-breathing and restful, just as they have longer lives than ours. They are wiser than we are, as long as we do not listen to them. But when we have learned how to listen to trees, then the brevity and the quickness and the childlike hastiness of our thoughts achieve an incomparable joy. Whoever has learned how to listen to trees no longer wants to be a tree. He wants to be nothing except what he is. That is home. That is happiness.’

Herman Hesse - Wandering

‘On its own, a tree cannot establish a consistent local climate. It is at the mercy of wind and weather. But together, many trees create an ecosystem that moderates extremes of heat and cold, stores a great deal of water, and generates a great deal of humidity. And in this protected environment, trees can live to be very old. To get to this point, the community must remain intact no matter what. If every tree were looking out only for itself, then quite a few of them would never reach old age. Regular fatalities would result in many large gaps in the tree canopy, which would make it easier for storms to get inside the forest and uproot more trees. The heat of summer would reach the forest floor and dry it out. Every tree would suffer. Every tree, therefore, is valuable to the community and worth keeping around for as long as possible. And that is why even sick individuals are supported and nourished until they recover. Next time, perhaps it will be the other way round, and the supporting tree might be the one in need of assistance. A tree can be only as strong as the forest that surrounds it.’

Peter Wohlleben, The Hidden Life of Trees

Image credit: Bored PandaStep three

Image credit: Bored PandaStep threeThink about the life cycle of a tree. Now imagine that your life is a tree. Where are you in your life cycle? Are you a sapling needing protection? Have you suffered a bad storm? Is your growth stunted? Is it winter or spring? Set a timer for ten minutes. Begin your writing, ‘I am a tree..’ Don’t read it back and don’t edit. Just write.

Image credit: Bored PandaStep four

Image credit: Bored PandaStep fourThink about a tree that is special to you. Perhaps it played a role in your childhood? It could be one you climbed, one in your garden, one where you met friends.

Why is it important?

Imagine you are there again as a child.

Who else is there, and what is happening? Set a timer for ten minutes and write.

Image credit: Bored Panda

Image credit: Bored Panda

Image credit: Bored Panda

Image credit: Bored Panda

Image credit: Bored PandaStep five

Image credit: Bored PandaStep fiveTake a japanese word prompt and use it to spark writing. You could write about when you last experienced this. Use the word as a jumping off point.

1. Komorebi

This word refers to the sunlight shining through the leaves of trees, creating a sort of dance between the light and the leaves.

2. Shinrinyoku

Literally “forest bathing,” shinrinyoku means walking through the forest and soaking in all the green light.

3. Kogarashi

The cold wind that lets us know of the arrival of winter.

4. Wabi-sabi

Although now used as a single word, wabi and sabi used to be distinct words and concepts. Originally, wabi referred to desolation and loneliness, but took on more positive implications around the fourteenth century when spiritual asceticism came to be admired. The meaning of sabi has also evolved from ‘withered’ to the beauty of passing time. These two words are now typically combined and sum up a key Japanese aesthetic rooted in Buddhist teachings—the imperfect, incomplete, and transient nature of beauty. Objects that elicit a sense of quiet melancholy and longing could be defined as wabi-sabi, such as wood that gains a mellow patina over time, falling autumn leaves, or a chipped vase. Wabi-sabi refers to a way of living that focuses on finding beauty within the imperfections of life and peacefully accepting the natural cycle of growth and decay.

5. Kogarashi

Literally ‘leaf-wilting wind’, kogarashi refers to the withering wind that comes at the start of winter and blows the last leaves off of the trees.

6. Mono no aware

This word combines mono, or ‘thing’, with aware, which means sensitivity or sadness, to connote a pathos engendered by a sense of the fleeting nature of life. This gentle sadness accompanied by a sense of the transitory nature of beauty lies at the heart of Japanese culture. Accepting this impermanence can lead to a sense of joy in the present moment, however insubstantial it may be, and even a recognition that beauty and intransience are two parts of a whole.

7. Yuugen

An awareness of the universe that triggers emotional responses that are too mysterious and deep for words.

8. Fuubutsushi

“The things – the feelings, scents or images – that evoke memories of the coming season.” This term is used to describe things like the smell of an Autumn rain, the fondness of running free through a Summer meadow or the freezing appendages brought on by snow.

9. Yugen

“A profound and mysterious sense of the beauty of the Universe, and the sad beauty of human suffering.” This is the feeling that we get when immersed in a forest or when climbing a mountain range. The feeling that you are so small and the Universe is so very large. The deep, emotional and yet often indescribable sense of connection with the Earth.

10. Boketto

“The act of gazing vacantly into the distance.” Perhaps an approximate translation might be ‘gazing enigmatically’. This term describes the look on your face while you are daydreaming or allowing your mind to wander.

Step sixLook at the images of trees in this post. Which one speaks to you and why?

The WildStep sevenMake a list of ten words that you associate with WILD.

Step eightRead these thoughts about wildness, paying attention, and letting ourselves wander.

For context: In Walden, Henry David Thoreau talks about his experience of living in a cabin in the woods that he built with his own hands. He lived off the land and found simple pleasures in nature.

‘Life consists with wildness. The most alive is the wildest…One who pressed forward incessantly and never rested from his labours, who grew fast and made infinite demands on life, would always find himself in a new country or wilderness, and surrounded by the raw material of life. He would be climbing over the prostrate stems of primitive forest-trees.’

‘In short, all good things are wild and free.’

‘We need the tonic of wildness... At the same time that we are earnest to explore and learn all things, we require that all things be mysterious and unfathomable. We can never have enough of nature. We must be refreshed by the sight of inexhaustible vigour, vast and titanic features, the sea-coast with its wrecks, the wilderness with its living and its decaying trees, the thunder-cloud, and the rain which lasts three weeks and produces freshets. We need to witness our own limits transgressed, and some life pasturing freely where we never wander.’ Walden, Thoreau

‘I come to my solitary woodland walk as the homesick go home… It is as if I always met in those places some grand, serene, immortal, infinitely encouraging, though invisible, companion, and walked with him.’ Walden, Thoreau

‘How wild it was to let it be’ Wild, Cheryl Strayed

‘I now walk into the wild.’ Into the Wild, Chris McCandless

‘I chose life over death for myself and my friends… I believe it is in our nature to explore, to reach out into the unknown. The only true failure would be to not explore at all.’ Ernest Shackleton

‘I have never witnessed a sight of the kind, which, in my opinion, was more beautiful that this. The colour of it far deeper and richer than any I have ever before seen. When I look at this, I sometimes wonder how I could ever have thought that beautiful; it seems so insignificant when compared with this. Around all is wild, all is silent. Yet we are in a country with which we are entirely unacquainted, no road, no compass, and at the point of starvation.’ William B. Dewees' Letters From An Early Settler Of Texas To A Friend

Step nineImagine you are out in the wild, alone. Where are you? Is it comforting or scary to be alone? What are you doing? How do you feel? There is a noise and you turn to look. What can you see?

Step ten: Homework1. Try to notice more. Always keep a notebook with you. Use all five senses in your writing.

2. Go on your own to a wild place. Sit and listen. Write a series of Haiku about what you can see or hear. (A Japanese form of poetry, with lines of 5,7,5 syllables.)

3. Go for a walk and be guided by one thing. Choose a colour, for example red. Notice everything that is red and write about it. Or notice things that have fallen to the ground.

4. Ways of seeing. When you notice an object, look at it, turn it around, hold it. Look at it close up and from far away. Think of different ways of seeing an object.

5. Focus on one tree in your neighbourhood. Notice how it changes throughout the year.

6. Make a collection of found objects to celebrate the season. Put them in your home and use them to spark an awareness of the changing seasons and joy.

7. Read The Red Tree by Shaun Tan if you haven’t already - it is wonderful!

I hope you enjoyed this self-guided workshop - let me know if you’d like more of this sort of thing.

Here is a copy of the workshop handout including all the quotes:

Trees And The Wild Handout165KB ∙ PDF fileDownloadDownloadThanks so much for reading Miners, and please forward it on to your friends if you think they would enjoy it too :)

Elisabeth

x

Miners is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.