III: The Poem's Sonic Signature - Sound, Rhythm, and Musicality

Beyond the visual and conceptual layers of a poem lies its sonic architecture. Sound devices are literary tools in which the very sounds of the words themselves—their vowels, consonants, and rhythmic qualities—profoundly impact the meaning and interpretation of the work. These devices are not secondary effects but are integral to the poetic experience, helping to build mood, create musicality, and reinforce theme. The skillful use of sound transforms poetry from a medium that is merely read to one that is heard and felt.

3.1 The Architecture of SoundThe emphasis on sound in poetry has deep historical roots. In ancient oral traditions, before the widespread availability of written texts, devices like alliteration, assonance, and rhyme were essential mnemonic aids, helping bards and storytellers to remember and transmit long epic poems and cultural narratives. During the Renaissance and Romantic periods, the function of these devices expanded to become tools for exploring complex emotions and the beauty of the natural world.

This evolution continues into the present day. In contemporary poetry, sound remains a vital component, finding its most potent expression in the realms of spoken word and performance poetry. In these forms, the poem's life on the stage—its rhythm, cadence, and vocal delivery—is paramount, bringing the art form full circle back to its oral origins. Contemporary poets use sound to reflect a vast range of personal experiences and cultural diversities, making the auditory landscape of modern poetry richer and more varied than ever before.

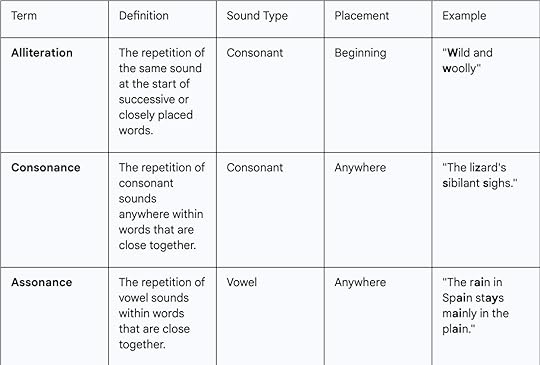

3.2 The Consonantal and Vocalic PalettesThe most fundamental sound devices can be organized by the types of sounds they repeat: consonants and vowels. The three primary devices in this category—alliteration, consonance, and assonance—are often confused, yet they create distinct effects. A clear understanding of their differences is essential for precise literary analysis.

Table 1: A Comparative Glossary of Sound DevicesTo provide immediate clarity, the following table delineates the key distinctions between these core devices. This visual guide clarifies the sound type (consonant vs. vowel) and the placement of the sound within the word (initial vs. internal), resolving a common point of confusion for students and writers.

3.3 Alliteration and Consonance in Practice

3.3 Alliteration and Consonance in PracticeAlliteration, the repetition of initial consonant sounds, has a long and storied history in English verse, serving as a key structural feature of Old English poetry like Beowulf. In later poetry, its function became more varied. In Edgar Allan Poe's "The Bells," alliteration is used for pure musicality, with the repetition of "b" and "s" sounds mimicking the merry chiming of silver bells: "What a world of merriment their melody foretells!". In contrast, T.S. Eliot employs alliteration in "The Waste Land" to a very different effect. The repetition of sibilant "s" and "sh" sounds contributes to a "sense of disjointedness and fragmentation," sonically reinforcing the poem's theme of a broken, sterile modern world.36

Consonance, the repetition of consonant sounds anywhere within words, offers a more subtle but equally powerful tool. It tends to create a "harder, more percussive sound" than the liquid flow of assonance. In Samuel Taylor Coleridge's "The Rime of the Ancient Mariner," the line "The fair breeze blew, the white foam flew, / The furrow followed free" uses both alliteration and consonance to create a driving, musical rhythm that mirrors the ship's swift movement. Sylvia Plath uses consonance to create a sense of urgency and intensity in "Tulips," where the repeated "t" and "l" sounds in "The tulips are too excitable, it is winter here" add a sharp, almost nervous quality to the line.

3.4 Assonance and the Shaping of MoodAssonance, the repetition of vowel sounds, is uniquely adept at shaping a poem's internal atmosphere or mood. Because different vowel sounds require different mouth shapes to produce, they can evoke distinct emotional and physical sensations in the reader. Soft, long vowel sounds like 'o' or 'oo' can create a soothing, calm, or somber effect, as in the line "The gentle lapping of the waves on the shore".

Conversely, harsh, short, or sharp vowel sounds like 'i' or 'e' can create a sense of tension, urgency, or distress, as in "The bitter cry of the raven in the darkness". Edgar Allan Poe, a master of sonic effects, uses assonance in "The Raven" to create a haunting and melancholic mood: "And the silken, sad, uncertain rustling of each purple curtain". The repeated short 'i' sound creates a sense of unease, while the mournful 'u' sound deepens the atmosphere of gloom and mystery.

3.5 Insight: Sound as Thematic EnactmentA sophisticated analysis of sound devices reveals that they do not merely support or decorate a theme; they can, in fact, enact it. The sonic structure of a poem can become a metaphor for its subject matter, allowing the reader to experience the theme on an auditory and visceral level. The way a poem sounds can tell its story just as powerfully as the words' literal meanings.

This principle is nowhere more evident than in Gwendolyn Brooks's iconic poem "We Real Cool." The poem's meaning is inextricably linked to its performance. The rebellious swagger of the "Seven at the Golden Shovel" is not just described; it is sonically constructed. The poem's clipped, monosyllabic words, the defiant enjambment that isolates the pronoun "We" at the end of each line, and the insistent internal rhymes ("Lurk late," "Strike straight," "Sing sin," "Thin gin," "Jazz June") all combine to create a percussive, jazzy rhythm. This sound is their "coolness." The poem's musicality embodies their carefree, rebellious lifestyle. This established sonic pattern makes the poem's conclusion all the more devastating. The final line, "Die soon," breaks the pattern. It is abrupt, unrhymed, and tonally flat. The music stops. This sonic rupture perfectly enacts the poem's theme: the seductive but ultimately fatal trajectory of the characters' lives is mirrored in the creation and subsequent shattering of the poem's musical structure.

3.6 Case Study: The Fatal Music of Gwendolyn Brooks's "We Real Cool"A detailed reading of "We Real Cool" confirms how sound enacts theme. The poem's subtitle, "The Pool Players. / Seven at the Golden Shovel," sets the scene. The voice is collective, defiant, and proud.

We real cool. We

Left school. We

Lurk late. We

Strike straight. We

Sing sin. We

Thin gin. We

Jazz June. We

Die soon.

The heavy use of assonance and consonance within the short, punchy phrases creates a series of internal rhymes that drive the poem forward with a confident beat. "Lurk late" and "Strike straight" are linked by both sound and a sense of aggressive action. "Sing sin" and "Thin gin" pair rebellion with consumption. "Jazz June" evokes a life lived for fleeting, seasonal pleasure. The placement of "We" at the end of each line (except the last) acts as a syncopated beat, a constant reassertion of their collective identity and defiance against the rhythm of a conventional sentence. This enjambment forces a pause, making the "We" an emphatic, almost boastful, declaration.

The poem's entire sonic world comes to an abrupt halt with the final two words. "Die soon" shares no rhyme with the preceding lines. Its rhythm is flat and final. The confident, musical swagger that Brooks so masterfully builds is extinguished in an instant, demonstrating with brutal sonic efficiency the tragic consequence of the life the poem describes. The sound, or lack thereof, delivers the poem's powerful, cautionary message.

3.7 The Full Orchestra: Euphony, Cacophony, and OnomatopoeiaBeyond the repetition of specific sounds, poets also manipulate the overall soundscape of their work.

Euphony (from the Greek for "pleasant sounding") refers to the use of smooth, harmonious, and musical language to create a pleasing effect. It is achieved through a combination of soft consonants, long vowels, and flowing rhythms. In contrast,

cacophony ("unpleasant sounding") is the deliberate use of harsh, jarring, and discordant sounds to create a sense of chaos, tension, or ugliness. This is often achieved with plosive consonants (like 'b', 'd', 'k', 'p', 't') and clashing sounds. A poet might use cacophony to describe a battle scene or a moment of intense emotional turmoil, matching the sound to the sense.

Finally, onomatopoeia adds a layer of direct sonic imitation to the poem. Words like "buzz," "whack," "clang," "sizzle," and "hiss" create an auditory effect that mirrors the thing being described, making the poetic world more vivid and immediate. While often used sparingly, onomatopoeia is another vital instrument in the poet's sonic orchestra, helping to create a fully realized and multi-sensory experience for the reader.

Subscribe to get Part IV directly to your inbox next week—IV: The Measure of the Line (A Critical Look at Rhythm and Meter).