'Cathedral Thinking' Can Make You Happier (& Change The World)

I must ask my father where the box is now. As a child, he would sometimes bring out his collection of treasures for my sisters and I to gawk at. Old coins, clay pipes and even interesting stones.

Each little trinket and treasure found between two giant slabs of stone laid down centuries ago.

Dad was a stonemason, a job that occasionally involves removing a worn or damaged stone from one of England’s many churches, cathedrals and ancient buildings. Most of these long-standing constructions have an inner and outer ‘face’ of stone with a rubble and mortar core.

It makes them incredibly stable, and also leaves a secret ‘gap’ where stonemasons who constructed them could leave a message, or a little gift, to the generations hence.

Your average time capsule has nothing on this. Dad would find 500-year-old graffiti on the back of the stones, the mason’s children’s names or often just shapes (unsurprising considering literacy rates at the time). Plus little offerings, often of a pipe.

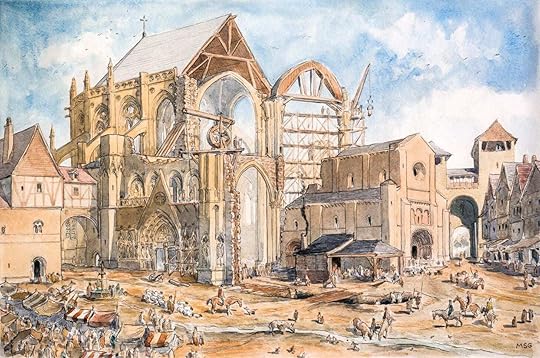

These people knew they were building for the long-term. A cathedral would often take generations to build, with the expectation that it would then stand forevermore.

What an incredible mindset to hold. That with luck (and the effort of future stonemasons), your works would last long after your name was forgotten.

At least, forgotten until a future mason found it carved on a clay pipe you’d hidden, just for him to find.

A short-term world

We live in a culture fevered by immediacy. The next quarter’s growth, the news alert, the scrolling feed. That conditioning warps our sense of agency and scale.

Psychologists call this temporal discounting, the bias by which people prefer smaller, sooner rewards over larger, later ones. Our brains are wired to devalue what lies in the dimmer future. This helps explain why we struggle to save, to plan, to act on climate or justice beyond our own lifetimes.

And it’s making us sad.

A 2023 systematic review of future-oriented thinking found that people who focus more on the long-term future show higher well-being, stronger goal persistence and more satisfaction with their lives.

Yet short-termism is not only psychological, it’s institutional. Richard Slaughter wrote as far back as 1996 that modern systems “reinforce the minimal present,” turning long-term vision into an act of rebellion.

We live inside a runaway present, where choice shrinks to the next minute. This narrowing empties out meaning, isolates us from continuity and robs life of the depth that a 16th-century stonemason enjoyed.

When we stretch time

Research shows that reaching beyond today is the ultimate act of self-care. Studies in temporal expansion reveal that imagining distant futures can reshape our identity, decrease stress, and strengthen our sense of purpose. One 2022 experiment found that asking participants to picture their lives from future vantage points made their goals more ambitious, compassionate and vivid.

The emotion of awe has similar effects. Dacher Keltner’s research at Berkeley shows that awe slows our perception of time, expands our sense of self and makes us more generous. Standing beneath an ancient oak or gazing at a mountain not only makes us feel small, but it also connects us to a timeline that transcends the self.

As a stonemason's daughter, I feel this deep connection to time when contemplating the Egyptian pyramids, Stonehenge, Göbekli Tepe, and Mohenjo-daro. Even walking my commute past the White Tower in London (constructed by William the Conqueror) can flip me into a deep time contemplation. I think about the builders who worked through generations on these monuments, for the sake of generations to come.

Moral philosophers have long understood the benefit of this ‘cathedral thinking’. Hilary Greaves and William MacAskill, in The Moral Case for Long-Term Thinking (2021), argue that the ethical weight of our choices does not decline with time. Distance in years should not lessen our responsibility to those who come after us.

Considering the selfish and short-termist obsession of much tech-culture, I love that computational models of cooperation show that societies which retain historical memory behave more altruistically than those that live only in the instant.

The longer our view, the kinder our behaviour.

The literature of long time

Storytellers have always understood what scientists are proving. In Ursula Le Guin’s The Dispossessed, the Anarresti build tunnels and institutions that outlast any lifetime so that each generation speaks in chorus with the past and future. Aldo Leopold’s essay Thinking Like a Mountain invites us to take the mountain’s view of time, to see human events as flickers within a vast ecology.

Roman Krznaric’s The Good Ancestor argues that every decision should be weighed by how it will be remembered, not how it will be rewarded. “Our descendants,” he writes, “depend on our ability to look beyond the immediate.”

Literature, philosophy and ecology all converge on the same truth: the long view is the human view.

Joy in the long now

People often assume that thinking far ahead must be gloomy. Too many people now envision apocalyptic timelines of melting ice and societal collapse.

But I am a stonemason’s daughter. I know that humans can build things of beauty and utility that will long outlast the names of those doing the building.

When we see ourselves as part of a long continuum, joy appears almost inevitably. Knowing that our actions ripple through generations grants meaning to the smallest gesture. Turning off a light becomes a love letter to the future. Writing a book or planting a tree becomes an act of devotion to people we will never meet.

Long-term thinking is also an antidote to anxiety.

When we place our lives within centuries rather than seasons, the petty urgency of the moment loses its grip. The inbox still fills, but it no longer defines existence. Purpose crystallises. Our days acquire an axis, and we join a human chain that stretches across time.

How to live the long now

You do not need to build a clock that ticks for ten thousand years to practise this.

Try writing a letter to someone who will be alive in the year 2300. Describe their sky, their challenges and their hopes. Do not predict, simply imagine with affection.

Spend time with something older than you: a tree, a cathedral, a fossil. Let it teach you patience. Read diaries from centuries past and feel the continuity of human worries and joys. Set a goal that must long outlive you. Speak about the future as though it is listening.

The pitfalls of the far view

Of course, long-term thinking isn’t entirely free from danger. Michelle Bastian warns of chronowashing, where invoking “future generations” becomes a way to justify delay or disguise inequality.

Also, beware of paralysis by scale, when the immensity of time overwhelms your ability to act. Not all futures are equally imagined; we must be alert to whose centuries are being centred. It’s not lost on me how many of the grand monuments of the past were also symbols of hierarchy and imperialism.

Some of the messages my dad found on the back of those stones aren’t of joy, but of grief. Because the long arc of history contains everything.

The long arc as a home

Living within the long now is not an escape from urgency. It is an embrace of continuity. It’s also why I still love the term' sustainability,' because it embodies that sense of long-termism within it.

When we expand our sense of time, we rediscover our place in the great unfolding of life. We become cathedral builders.