Harry Harrison Centenary – Part 12: Men’s Adventure Magazines 2

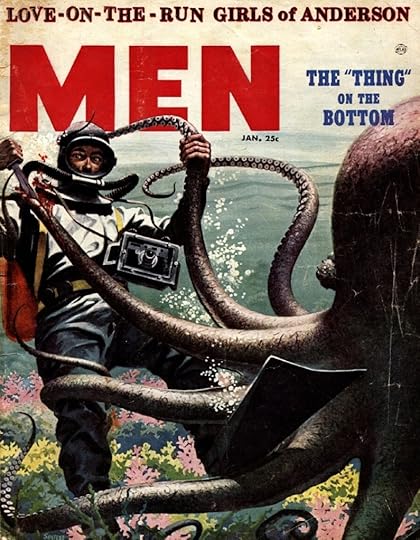

Men Vol.5, No.1, January 1956, edited by Noah Sarlat. Cover painting by Frank Soltesz for the story ‘The “Thing” on the Bottom’ by Joseph Santio. Image from PulpCovers.com

Here is one of Harry Harrison’s earliest men’s adventure articles – there were three published in January 1956. This one closely follows the ‘formula’ that I referred to in the last post. I’m not sure if Hubert Pritchard collaborated on this one or not. The accompanying photograph (see below) is uncredited. Some of the photos HH submitted with his articles came from picture libraries, and some were staged by him using people he knew.

The story may have been based on a true event, though I’m pretty sure Harry Harrison didn’t interview anyone called Captain Wilner for the details included here: everything came from his imagination. I did a quick Google search and couldn’t see that Waterhouse Victory was an actual ship. Article length c.3,000 words

The tagline on the index page reads, “She was heading for the bottom and I couldn’t get out.”

I Went Down with My Shipby Captain M. Wilner as told to Harry Harrison

“As she tilted crazily on the ocean floor, I floated around in the water-filled cabin, trying not to use up my last three feet of air.”

The ship gave another sickening lurch and I knew she was sinking. With the floor tilted at a 45-degree angle, I couldn’t keep my footing. Skidding and falling, I crashed against the bulkhead.

Everything had happened so fast there was no time to think clearly. Only one thing kept echoing around in my head: You’re Captain of this ship, why aren’t you on the bridge when she’s in trouble? I didn’t consider my own life, not then. All I knew was that I was locked in the radio room while my ship was heading for the bottom.

It was like climbing a wall to get to the door but I did it, hand over hand. I turned and pulled the handle but it was no use, the damned thing was jammed.

I was pulled loose from the door as the ship rolled again, a slow, frightening roll that didn’t stop. The lights went out then and I tumbled down the bulkhead with all of the loose equipment. The roll finally stopped, but the ship had turned completely over! There was a feeling in my gut, the kind you get when an elevator goes down too fast. We were on the way to the bottom. The ship was sinking and I was trapped inside of her.

A sudden roar blasted through the metal of the hull, followed by a tremendous hissing and bubbling as the sea water reached the engines. That explosion had been the death blow, the escaping steam was her death rattle. I floundered there in the darkness as we slid toward the bottom, waiting for the end. After a few moments the noises diminished, except for the creaking of the hull plates as the pressure worked on them.

At any moment now the steel walls of the radio room would be squeezed in and I would be crushed under a million tons of water. I wasn’t frightened; my mind was numb. I wasn’t thinking or, feeling. I and my ship were alone down there in the eternal darkness; we were going to die together.

The ship touched bottom, sinking into the ooze slowly, tilting as she settled. A sudden roar shattered the intense silence as some of the bulkheads gave way under the pressure. The water foamed up to the radio shack. I felt the door shake and was splattered by a jet of icy water that sprayed in around the jam.

It was the end.

Photo: Uncredited

Photo: UncreditedDrowning men are supposed to see their lives flash before their eyes, a sort of speeded-up newsreel, but that’s so much bilge. I didn’t see a thing except stars from banging my skull against the transmitter. I was angry, too. The Waterhouse Victory was a new ship and this was her maiden voyage. The crew and I had sweated blood getting her into shape.

She was a war baby, turned out by a bunch of ham-handed welders who in peacetime couldn’t have landed a job soldering tin cans together in a sardine factory. She was slow and we almost ripped her turbines out, but we managed to keep up with the convoy. The wolf packs were out and we had to dodge them all across the Atlantic. We would have docked the next day – if that tin fish hadn’t found us first.

The funny thing was, none of us were expecting it. We were off the coast of Madagascar, running near the center of a hundred-ship convoy. Land-based planes swept this area every day, and the sea was thick with tin cans and DE’s with listening gear.

The intelligence report said that the area was clear of subs. When we heard that we all eased up and began to feel as if the crossing was behind us. We still slept with our shoes and life-jackets on, but at least we slept. I made sure each watch had some decent sleep, then we got to work on the ship. Two straight weeks at battle stations and you have a filthy ship.

She was a mess. Broken gear in the passageways, shell casings underfoot wherever you walked, and decks as filthy as an island trader. We couldn’t throw the gear over the side because subs could track us by it. I had it all pushed in on top of the cases in number 2 hold, figuring to get rid of it when we hit port.

A heavy sea had washed right over the Waterhouse Victory the third day out, stoving in all the starboard windows on the bridge. We had rigged temporary canvas covers, but they were awfully drafty. These were taken down and wooden covers battened into place. When I saw that things were going well, I went into the radio room to look at the latest BAMS message. My First Mate, Costello, was on the bridge, the ship was in good hands.

Sparks handed me the sheaf on the clipboard and went back to monitoring the emergency frequencies. I never had a chance to look at the BAMS – the deck jumped under me and I was hit by a sound so loud it was as solid as a wave of water.

Sparks was on the floor, bleeding from the mouth, too groggy to move. I picked him up and slammed him into his chair. He was coming out of it, groping for the key. I dived for the speaking tube to the bridge and tore open the gas lid.

“Costello, what the hell was it?”

It couldn’t have taken him more than seconds to answer, but it seemed like hours to me. I hung there, cursing, until his voice rasped back.

“Captain… we we took a torpedo aft. The sub must have been lying on the bottom waiting for the convoy to come over her.”

“All right. Hold on. I’m coming up!” As I turned from the tube I saw Sparks hurl down his phones and dive for the battery room. He shouted over his shoulder:

“Power is off, Captain, have to hook in the auxiliary.”

A second explosion hit then; it must have been the ammunition in number 3 hold. That blast ripped out the bowels of the Waterhouse Victory, because she reared up like a wounded animal. The deck tilted like a coal chute and I slammed back into the transmitter. Everything seemed to break lose at the same

time and rain down on me. I saw the door swing out and slam shut. It was like climbing a gabled roof to reach that door, but I managed to do it. I swung from the handle, but the door was jammed.

Sparks would have to help me. I couldn’t force it alone. I skidded in back to the wall and over to the door of the battery room. My angry shout to Sparks died on my lips.

He sat against the wall with his eyes open. staring at me. He wasn’t seeing me though, his skull had bashed into the corner of the battery rack with the last explosion. It had put a five inch hole in the bone. Must have killed him instantly.

The ship was still listing badly. I had to find out what was going on. I grabbed the speaking tube again and got Costello back.

“Captain, the main shaft’s cracked and we’re taking water in over the stern into hatches 3 and 4. Six dead in the engine room – they’re filling up fast – twenty degree list to port!”

“Clear the wounded from the flooded compartments, then abandon ship. I’m locked in the radio shack. I’ll be there as soon as I can find something to break the door down with.”

That was when the Waterhouse Victory started her long slide to the bottom. I’d seen it happen to other ships – from torpedoing to sinking, maybe eight minutes. Now it was happening to me.

I realized then, for the first time, that I was going to die. I had been too concerned about the ship to think about any personal peril. Now there it was, staring me right in the eye. We were on the way to the bottom and there was nothing I could do about it, except go down with my ship.

With the lights out and the grave-like silence of the sea all around, it was like being buried in a giant, steel coffin. When the ship hit bottom I knew that this was it.

The seconds ticked by, each one seeming the last, as I waited for sea to crash through the bulkheads and destroy me. The water rushed up to the door of the compartment and pressed against it. I could feel the thin, cold streams that spattered in around the frame. A rock-hard stream hit me from behind, knocking me off my feet. At first I thought the bulkhead had given way, until I realized it was a jet of water from the speaking tube, forced through it from the bridge.

There was water up to my knees now and it was rising fast. My ears cracked as the incoming water compressed the air. In a few minutes it was up to my armpits, and then I was floating. I should have

been dead and I wasn’t yet; at this instant my first spark of hope was born.

The Waterhouse Victory must have sunk over the very edge of the reef that extends out from the Madagascar coast. The reef here was about 300 feet down. Where it ended, the drop went down to

over a mile. I guessed the ship was on the reef from the length of time it took us to sink. Even as I thought this, the ship shuddered and fell a ways before grinding to a stop. At any moment she might sink into that mile deep valley.

If I could get out of the ship now I might stand a chance of reaching the surface alive. However, if the ship took that mile plunge, I would be crushed long before we reached bottom. I had to at least try to get free.

The water had stopped rising in the compartment, evidently the pocket of air that was trapped there had been compressed to the point where it could withstand the outside pressure. I didn’t know how long this air would last. I had to get out while it was still breathable. To do that I needed a light. There was a waterproof flashlight in one of the file drawers. I had to find it.

It was like swimming in a nightmare. I felt along the wall until I got my direction, then took a deep breath and dived. I ran out of breath before I located the drawer and had to come up for air. On the fourth dive I found the flashlight, surfaced, and turned it on.

I treaded water and threw the beam around the compartment. It was filled almost to the top with black water. There was about three feet of airspace left between the water and what used to be the floor. The door that opened out of the radio room was on the far bulkhead. I pushed over to it. I tested it but it didn’t budge, still jammed tightly shut.

This door would be my first barrier; there was a companionway outside and another door to get through before I was out of the ship. That door led out onto the upper deck which, since the ship had turned turtle, might be buried deep in the mud. I would face that possibility when I came to it, right now I had to open that jammed door.

I had a clasp knife in my pocket, a big one that I had carried ever since I first went to sea. After I shoved the blade into the crack between the door and the jamb, I levered it back and forth as hard as I dared. The door wouldn’t move. I pushed harder and the blade snapped. There was a stub of blade about an inch long left; it barely fit into the crack of the buckled frame. I breathed a silent prayer and pushed it in. Slowly and reluctantly the door shifted. The knife dropped from my fingers as I jammed my

shoulder against the door.

It gave all at once and fell open – and took half of my air with it! What was now the top of the door had cut halfway across my airspace; when it opened that much air rushed out. When I treaded water now, my head hit against metal above me. This bit of air that was left was already getting foul. It was time to

get out.

For a moment, I lost my nerve. I visualized the tiny, crushed wreck of the Waterhouse Victory lying there in the muck of the ocean floor. I saw the schools of fish that nosed about it and the awful weight of the water on top. There was no way of knowing for sure how deep the water was, but it must be at least 300 feet. Without breathing or diving equipment of any kind, I had to force my way up through that water to the surface. The choice had to be made. If I stayed in the ship it was certain death; if I tried for the surface I had some chance of getting through, no matter how small.

I was getting out. The first thing was to get rid of extra weight. I kicked off my shoes and managed to struggle out of my heavy jacket. Then I held onto the door frame, so I wouldn’t have to tread water, and started deep breathing. I’ve seen native fishermen in the islands and Japanese pearl divers do this. They soak their bodies with oxygen for deep dives and stay under water for minutes this way. I did as much deep breathing as I could, then took one last big lungful of air. Holding the flashlight in front of me, I dived down through the door.

It was about 30 feet along the passageway to the outer door. I made it as fast as I could and grabbed the edge of the door that was standing halfway open. When I pulled it to me and pointed the flashlight through the opening I almost gasped out all my air. There was a wall of mud outside.

I reached up to the top and pushed with my free hand, the mud seemed looser there. I dropped the flashlight and took the only chance I had. Kicking with my feet and pushing against the door frame

I forced my head into that black muck. It closed about me. I could feel it being forced into my nose, my ears. I could only have been in the mud for a few moments, but it was forever. My hands were free of the door jamb so I set my feet against it and pushed as hard as I could. Reluctantly the mud gave up its hold and I was through into the water.

I blew all the air out of my lungs and started swimming for the surface hundreds of feet above. It was the hardest thing I ever did. Every part of my body said hold your breath, yet I knew I would be dead if I did. One important fact I’ve picked up from the divers I have known is that you can’t come up with a lungful of air under pressure. As you rise higher in the water the air expands, so that by the time you make the surface, you’re dead, with your lungs exploded into a bloody mess by the internal pressure.

I forced myself to get rid of that air, breathing out till I could breathe no more. Then I swam. It was midnight black. I couldn’t see the surface, but I knew I was rushing upwards. I thrashed hard, swimming for my life. There was a ringing in my head and I had to breathe, but I knew there was only water to breathe. Far, far in the distance I saw a glimmer of light that might be the surface, but it was too far away. My eyes were fogging and I had trouble moving my arms and legs. This was nothing compared to the fire in my chest. I had to breathe and I couldn’t stop myself. I knew there was no air, but my body was beyond control now. I inhaled through shaking lips – breathed in pure sea water that burned like molten lead. The water was in my mouth, my lungs. I was choking – dying.

I gasped again and breathed air. My body shot up from the water and flopped back. There was just time for one wonderful breath of air before I was below the surface again. I broke through the surface a second time, gasping and choking on water and blood. As the ache died away in my lungs I became aware of the racking pains that were clutching at my knees. The bends! The pain was gigantic, it curled my legs so I couldn’t use them. I floated with only my arms for support.

The most wonderful sight I have ever seen was the thin, gray bow of that destroyer cutting through the water towards me. I knew they always picked up the survivors of a sunken ship, but so much time seemed to have elapsed I was sure they were gone.

They threw down a rope, but I was too weak to grab on. Two sailors climbed down the Jacob’s ladder and one held me above the water while the other passed a rope under my shoulders. My last memories were of being hauled from the sea like some dripping fish…

I have a desk job on shore now, which is about all the job I can handle with a stiff leg and a chest that still hurts in cold weather. But I’m not complaining, because I got out. Half of my crew are still down there, trapped forever in a rusting hulk on the edge of the Madagascar reef.

Paul Tomlinson is the author of over a dozen novels and books about writing genre fiction. www.paultomlinson.org

Harry Harrison's Blog

- Harry Harrison's profile

- 1036 followers