ROOTED IN THE BOWELS OF THE EARTH: Whipple, Wallowing, and Recovery

Solid pseudopapillary neoplasm by Omid Savari, M.D.

Solid pseudopapillary neoplasm by Omid Savari, M.D.

“Novels, one would have thought, would have been devoted to influenza; epic poems to typhoid; odes to pneumonia, lyrics to toothache. But no; with a few exceptions… literature does its best to maintain that its concern is with the mind; that the body is a sheet of plain glass through which the soul looks straight and clear. On the contrary, the very opposite is true. All day, all night the body intervenes… But of all this daily drama of the body there is no record… To look at these things squarely in the fact would need the courage of a lion tamer; a robust philosophy; a reason rooted in the bowels of the earth.”

Woolf, On Being Ill

Author’s note: I wrote this because a lot of people reach out to me on social media to ask about my experience having a Whipple. They are either getting one or supporting a loved one who needs to undergo the procedure. Despite this procedure being pretty rare, this request for information happens fairly frequently. I wanted to share my experience and give people an in-depth view of having this procedure and the recovery process while also offering some encouragement. If you’re wondering why this is in second person, its because I initially started writing this in response to someone asking what they could expect with the Whipple. But then I started talking to my past self, a different self than the one writing this paragraph. I hope you find it helpful, whoever you are, and good luck.

You’re doubling over in the moonlight as it turns the warm rocky Sante Fe shrubland into impasto shades of blue, silver, and slate. A sharp, throbbing pain jabs into your lower flank and your stomach cramps in ways you haven’t felt since before you started taking birth control. Its your last visit to see your partner before they move to Portland–to you–so you can live together. This will be the first time you live with someone not your family. That realization makes this final trip heart-poundingly sweet, every moment one of grateful shock. You are so in love it makes you dizzy to think about it for long. It all feels too good, too correct, like a painful, knotted muscle finally loosening. And sure, there’s fear because anything truly life changing is impossible to take in stride. But then your back throbs, a deep pulsing pain. It’s midnight and you’re in the ER. You cry while you wait. Going to the ER reminds you of the handful of embarrassing times you had asthma attacks and were rushed in and put on oxygen. All because you couldn’t manage the most basic aspect of your body: breath. Your partner reassures and calms me. Probably just a UTI, you think.

The doctor on duty orders you a CT scan even though its unusual for a UTI. He wants to make sure there’s no kidney infection. You wait for the results for an hour or two, nerves whittled down by exhaustion. Your partner cuddles with you on the small hospital bed ans you watch Real Housewives of Somewhere, letting the campy drama dampen your anxiety. When the doctor comes back to your room, his eyes are alert and there’s insistent energy as he sits down and looks you in the eye. He confirms you have a UTI but he also found something else incidentally, something you need to get looked at urgently. An orange-sized tumor in your pancreas. This is serious, he says. You say you’ll get it looked at when you get home.

Immediately, he says. You cannot wait.

The pancreas is a vital organ that lies in the upper belly, behind the stomach. It works closely with the liver and the ducts that carry bile.Your partner drives you both home under chilly moonlight and glowing neon signs. You stare out at the scrub and stone, disassociating and then tearily panicking in silence. The landscape feels nightmarish, like the shadows will suck you straight out into the empty desert and disperse you across the sand like the coagulation of dust you are. Santa Fe had become a place vast and magical to you; its where you met your partner in real life, where you started understanding what romantic love really was. But tonight, it suddenly looks brittle and tomb-like. You google the fatality rate of pancreatic tumors. For localized (there is no sign that the cancer has spread outside of the pancreas) the 5-year relative survival rate is 44%. For regional (the cancer has spread from the pancreas to nearby structures or lymph nodes) the 5-year relative survival rate is 16%. For distant (the cancer has spread to distant parts of the body, such as the lungs, liver, or bones) the 5-year relative survival rate is 3%. Pancreatic cancer often presents little to no symptoms before its Stage 4 and fatal. The statistics start to run together through your tears. You don’t feel death that close and yet it might be just around the corner, waiting for you in symptomless silence. A big, cold hollow splinters open in your chest. Your partner reassures you as they drive but their voice becomes gibberish. You are inside yourself, your dying self–you were always dying, yes–but faster now, much faster, and when you’ve only just started living. You try to enjoy the last day of your visit with your partner at an outdoor festival. You listen to a band play in someone’s yard, holding your partner’s hand, swaying, until the mediocre music seeps into your skin and your eyes start to burn. This might be the last concert you’ll see and its not even that good.

You already ended one life earlier this year. You come out to family, friends, and community knowing that, for the majority of them, the truth of you will leave them only one option: to cut you off. But you cannot hide yourself anymore, you cannot exist meaningfully in the sludgy, unmoored mire between their desires and your own. You have been gluttonous, choosing yourself over everyone else. When you come out, over text and phone call and a post online, you get the reactions you expect. Eulogic and angry, disappointed and self-righteous, pity and disgust. They call and plead with you to turn back to god, to not make this horrible soul-destroying mistake. Some simply ghost you. To them, you are committing spiritual suicide, closing off the possibility of afterlife by taking part in the worst of sins. Even more hurtful is that you are forcing them to cut you away, like a spiritual cancer. They cannot risk being tainted by your lifestyle. Later, when you share about your actual pancreatic cancer online, there are no messages from these people. You wonder if they feel vindicated. “And you will suffer with many sicknesses, including a disease of your intestines, until your intestines come out because of the disease, day after day.” It is only appropriate that this tumor will end your life for your numerous sins. You get to be proof, an affirmation of their faith, that your transgression of loving someone you shouldn’t will not go unanswered by god. This is what you get for gorging on all you desire for the first time in your life, heedless of the expectations you’ve shouldered since childhood.

The pancreas releases proteins called enzymes that help digest food. The pancreas also makes hormones that help manage blood sugar.It takes you a month of blood tests, CTs and MRIs to diagnose the tumor. You eat very little, constantly aware of the alien mass in your gut that shouldn’t be there. Sometimes you hallucinate a rippling sensation deep in your abdomen and wonder if its finally metastasizing. If you’re going to wake up one morning and be stage 4, at death’s door at the speed of a blink. In that time, you wonder if you should cancel all your book contracts (you put them on hiatus). You wonder if you should move away from your family (you don’t, too exhausted and afraid). When confronted with the idea of dying, you want to do it alone, maybe by your own hand. You research Oregon’s Death with Dignity Act to see if you’ll be able to qualify. A nauseating, shadowy weight bears down on you heavier everyday you don’t have answers. You blame yourself for how you’ve treated your body, hated it, disconnected from it just to tolerate existence. Its only been a few years since you’ve been able to find pleasure and beauty in your body. You admire its strength and wonder in how it carries you towards the things and people you want. Now all that wasted time spent neglecting it looms at your back, large and reeking as a landfill. Time thins, becomes a brittle shelf of fear and grief you walk across and try not to crack.

You vacilate between suicidal surrender and furious, determined hope. You wonder if you should break up with your partner and grapple with which is crueler: forcing them to watch you die or forcing them to move on without you. You have only been dating a year but your life has changed because of them. The core of you has changed, unearthed and witnessed without any protective shrouds. The sweetness and joy and passion they bring to your life is something you have never experienced before. This is not something that you can let go of now that you’ve had it. You need them. If you only get a few months more with them, you can’t think of a better way to spend the rest of your life.

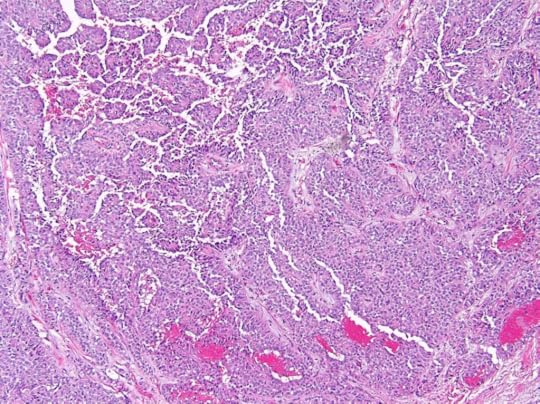

Pancreatic cancer, often referred to as a silent yet fatal disease, is notorious for its insidious onset and the excruciating pain it can cause during its advanced stages.The mass is identified as a solid pseudopapillary tumor, a growth that presents in younger women, classically as solitary body / tail mass. It is encapsulated inside its own membrane and has not spread. You do not need chemotherapy but you do need to get it out quickly. They give you a few weeks to help move your partner and their ex in. You try and enjoy your last weeks before surgery with your partner and celebrate the milestone of moving in together. There is no preparing for your procedure; it is extreme, hard on the body, and complications will vary. You try not to fixate on it but anxiety hums constantly in the back of your mind. Your partner does their best to keep you grounded in the present. You eat decadently, you dance, you make art. You make peace. You write a will. How you lived your life wasn’t anywhere close to perfect but it was good. The days before surgery were the sweetest you’ve ever had.

The Whipple procedure is also called a pancreaticoduodenectomy. It's often used to treat pancreatic cancer that hasn't spread beyond the pancreas. The Whipple procedure is a complex operation. It can have serious risks.Your parents are there even though they can’t stand seeing each other after their divorce two years ago. Your siblings are there to keep them in check. You tell your partner, a therapist, to ignore them if they start to fight. They don’t need to do a free family therapy session on top of worrying about you. On the day of the surgery, they take you back early in the morning and put you in a gown and grippy socks. You pose sexily for your partner as you wait, your mood anxious but somehow light. There’s no turning back now, what needs to be done will be done. After taking your vitals and going through paperwork, they give you an nerve block in your spine. They miss a couple times, scraping against your vertebrae with a needle. It makes your teeth tickle queasily. Your kiss and hug your partner and family goodbye and then you’re carted off to the operating room.

The Whipple procedure might be done as open surgery. During an open operation, a surgeon makes a cut, called an incision, through the belly to get to the pancreas. This is the most common approach.You focus on your breathing, slow and deep. If you let even a little fear seep in, you worry you’ll stall the procedure with your high pulse. The operating room is piercingly bright and cold. The medical equipment looms overhead, intimidating and arcane. Hawaiian music plays overhead because one of the nurses attending is Hawaiian. It settles you. They tell you to count backwards from 10 and put the mask over your face. The edges of your vision tunnel and then within a few seconds, you’re asleep.

A dreamless 12 hours will pass like nothing for you.

The surgery removes the head of the pancreas, most of the bile duct, the gallbladder, duodenum, and a small portion of the stomach. Once the organs are extracted, surgeons reconnect what is left of the pancreas, bile duct, and stomach to the small intestine.When you wake, your throat is dry. You sit in a long, empty room with a nurse as you get your bearings. The epidural has numbed the pain but you feel distinctly weak, the edges of your body watery and permeable. They cart you to the room you’ll recover in for the next eight days where your partner and family waits for you. You don’t remember much but you feel exhausted relief to feel them around you. A drain runs out of your nose and three run out of your stomach, diverting pancreatic fluid and any extra abdominal fluid that might pool inside you. Your ten inch incision runs from the bottom of your sternum to below your bellybutton. Your surgeon, so kind and encouraging throughout, has hand-stitched instead of stapled the incision to try and keep your belly tattoo aligned; its nearly perfect. He also tells you that your tumor hasn’t spread anywhere else, that its been removed before it could metastasize. This is the ideal result. You are relieved but you feel like you’re still escaping death so it doesn’t quite sink in. Your body feels flimsy and disconnected, like you’re wearing something instead of inhabiting it.

The next few days you’re on strictly water and a little bit of ice. They tell you your newly-reconstructed guts are asleep. They need to wake up little by little. The surgeon has connected parts of your intestine to your stomach, pancreas, and bile duct. The openings are new and raw, the droplets of acid hitting tender enteric flesh not used to such corrosive bile. Your partner sleeps with you on the narrow hospital bed, your arms and legs tangled up as you hide under a blanket they’ve brought from home. The nurses and doctors constantly tell you how sweet you both are; caring for someone with a Whipple is difficult work, especially your partner who has more on their plate than any one person should.

After a few days of ice and juice, you begin trying more substantial foods. You have a hopeful appetite and the anti-nausea medication in your IV makes you bold. You start with small bites every few hours. Then you scarf a few bites of bland hospital pasta and manage to keep it down for a few hours before you vomit it up. Your digestive system isn’t fully awake so the food just sits there in your stomach until its forced to come back out. This becomes a pattern, eating and vomiting, trying to coax your traumatized organs into playing their new role. The cycle is expected but miserable. Your gums start to hurt from all the acid washing them when you vomit. They give you a laxative and you’re finally able to have a bowel movement. Your body is re-learning its functions one step at a time.

On the 7th day, you need to get outside. You’ve been pacing the recovery floor frequently because walking helps with digestion. But you’re sick of the cold white walls and seeing the world through windows. Your hospital room is starting to close in on you and you desperately want to leave. Your mom wheels you down to the courtyard to get some air for the first time. You immediately start to cry, feeling the sun and the breeze on your dry skin. It feels like the sunlight will punch right through you, like you’re made of nothing stronger than tissue paper. You have lost 40 pounds in a week, your body eating away at you because theres so little else to nourish it. Your joints ache with every movement, no padding around the hard points of your body from all the burned fat. Every movement emphasizes a new shocking weakness you didn’t know your muscles were capable of. Your sit bones throb against your wheelchair, the pressure like a bruise. You can’t stand feeling this painfully frail but you can’t imagine how long it will take to recover either. You tell your mom and your partner you want to leave, you need to leave. Your doctor says you can go if you can make a bowel movement and keep down food for a whole day. With determination and careful pacing, you do.

On the 8th day you go home. The drive back is painful, nauseating. You hold a green plastic bag in front of you just in case you vomit. Your dogs howl and cry when they see you and you touch them gingerly, trying to make sure they don’t tangle in your pancreas drain. You gently shoo them out of your room to settle into your own bed, comfy and plush, not like the stiff hospital bed you’ve been in for over a week. For a moment, you think it’ll all start getting better now that you’re home. Then you slowly nosedive. You take Creon tablets to replace the digestive enzymes you’re not getting while your pancreas fluid is diverted into a drain bag. You can’t swallow pills anymore because it triggers you to vomit so you empty the pills into yogurt. The hard little Creon pebbles get stuck in your teeth. Everyday is a plodding pattern of testing the fortitude of your stomach, fighting exhaustion, depressive spirals in between brain fogs.

You take a bite, wait to see if it’ll come back up.

You take a bite, wait to see if it’ll come back up. Your stomach burbles.

You take a bite, wait to see if it’ll come back up. Some organ clenches, churns.

You take a bite, wait to see if it’ll come back up. You hope, hope, hope to keep it fucking down this time…

And then your throat burns as a bile pushes up from your stomach, the soup a touch past your tolerance.

You have never paid this much attention to a singular function of your body. Your doctor recommends around 80 grams of protein a day and you can’t imagine reaching that number with the meager amount you’re able to stomach. You have never been a big eater and now you practically need to eat all day, one bite every 10 minutes just to keep you from passing out. Your brain and stomach are in perfect miserable sync. A calorie deficit equals an equally proportionate deficit in cognition. You want the benefits but you have no appetite, only unending queasiness at the thought of food going down your gullet.

You start vomiting cyclically, every afternoon and every evening no matter what you eat. Nothing stays down. You tiredly empty your pancreas drain bag twice a day. Sometimes you drop the bag or your dogs jump up on you, yanking on the drain line in their claws and tugging painfully on your pancreas where it’s stitched. Your body feels more like a patchy, quivering suit coming apart at the seams then it does something organic and part of you.

“Pain is always new to the sufferer, but loses its originality for those around him. Everyone will get used to it except me,” says Daudet in In the Land of Pain. You wonder if caring for you will break your partner, your repetitive abjection as irritating as it is burdensome. You wonder if they’ll fall out of love seeing you are your weakest, most disgusting, most boring. You can’t even have sex, not for several months, until your incision heals. Even if you were healed enough, sex is the furthest thing from your mind; your frailty and nausea throttle every erotic urge, every sexy thought. The most inoffensive taste, a vague scent, or the wrong pressure on your throat, will send your stomach spinning, which includes sweat, spit, a hint of body wash. Your body cannot stomach any other bodies right now, it can barely handle its own. You are constantly cold and your skin is dry and loose. No touch elicits pleasure, only a reminder of how weak you are, how much you’ve changed, how it hurts.

You have always been fat and it took you until your late 20s to finally settle into it, your 30s to appreciate and revel in your rolls, the apron of your stomach, the weight in your ass and thighs. Now it’s all gone, skin hanging flaccid from your skeleton, scored in new stretch marks made by gravity pulls at the newly deflated flesh. It is hard to see anything appealing to your body beyond its ability to persevere in its survival. You don’t see how your partner, so adoring of your fullness and weight, could find anything about you attractive now.

In Becca J.H’s essay ‘The Meaning of Suffering’, she writes, “Maybe the reason that great artists don’t focus on the pain-state is not because they are disinterested in it, or because art cannot capture suffering, but because they recognize the futility of lingering within severe affliction. Great art makes meaning out of things. If art makes meaning out of illness, it does so in the way we all do: by following the movement out of suffering, by capturing its associated revelations and epiphanies, by pursuing the heightened-consciousness that comes out of pain.”

You are starving and there is no meaning in it. Nausea is its own flavor of pain, a function that ties your brain and gut together in an untangleable braid, commanding all attention to one’s most infantile function. There is pain from weakness alone; every movement a bruising tension on your muscles, radiating soreness in your joints. Since you have no muscle or fat to burn, you feel your flesh turn on your brain. Starvation dampens deep thought. You can’t focus or read and the idea of making art, the practice that has served your soul for its entire existence, seems laughable. You can barely hold a single idea in your head, everything floating into an indistinguishable and shallow fog at the fore of your mind. You feel an overwhelming sense of emptiness, unable to follow lines of thought. Clipped, superficial ideas dissolve into mist. You don’t want to watch movies because you have so little attention to offer; at the worst of times, which is most of the time, you feel like you’re watching globs of colorful light and emotive sound. You have so little capacity to pay attention or to hold a conversation. “To be sick in this way is to have the unpleasant feeling that you are impersonating yourself,” observes Meghan O’Rourke. “When you’re sick, the act of living is more act than living. Healthy people, as you’re painfully aware, have the luxury of forgetting that our existence depends on a cascade of precise cellular interactions. Not you.” You obsess over each churn of your gut, whether you burp or shit, how bloated you feel.

You develop a severe anxiety whenever you puke. There is no sign of when it will happen beyond a sudden hot pressure in your throat as it begins, no watering mouth, no nausea. You are sitting or staring at the TV and then suddenly everything is coming out of you. All your thoughts are consumed by fear of entering another cycle of vomiting, of watching your body degenerate further until you are skin and bones and then nothing. You feel immense guilt that sits on you like a gummy sweat. You cannot control when you backslide, it is up to the whims of your body and nothing else. Your partner nobly cleans up after you, waking up at midnight to change out the trash can you’ve filled. They’re caring for you while also completing their practicum, seeing therapy clients full-time everyday on top of cleaning, cooking, caring for your three dogs, and navigating living with their ex with whom you both unfortunately live.

You end up hospitalized two more times for a week each. You go through the ER, waiting for hours before your admitted. The first time you nearly pass out waiting, caught in another cycle of vomiting.The second time is for a painful pancreatic leak which has caused a small cavity of liquid to expand in your abdomen. Even though you find relief during your stays, they are exhausting and depressing. You thought you were progressing but not so. After, when your return home, a new anxiety begins to tear around in your head. Every time you vomit you begin to have a panic attack. You link the violet surge of hot bile and partially digested food with another miserable stint at the ER, or another endless cycle of random regurgitation. The anxiety spikes your pulse, makes you nauseous just from the fear and anxiety alone. Your body is not your own. You are not in control. It no longer wishes to serve you. In the span of a day, you’ve gone from fully able to a state of helplessness and pain you were not prepared for. Yes, this is the end state for us all and you are no stranger to contemplating your mortality but the practice of sickness is different from the theory of it.

Your partner reminds you daily, hourly, that this pain is only temporary. Its hard to hear your own voice in your head so you echo theirs instead. Your nurse tells you to treat your body like a newborn; it knows nothing of how to eat, to digest, and needs to learn from square one. You don’t punish a newborn for vomiting, for sleeping hours on end, for doing nothing. As someone who often manages lots of group initiatives, creative projects, who makes art and is generally active, doing nothing unsettles you. You are never bored but now, in your cognitive helplessness, you are listless and useless to quench it. You turn to digestible TV shows and the occasional comfort movies, things you don’t feel guilty about dozing off to. This sluggish airheaded possessing you lasts for months, your ability to concentrate whittled away by malnutrition.

At the end of your third month, the sutures keeping your pancreatic drain in place finally dissolve. The drain hole snaps shut thanks to your surgeon’s fancy stitchwork. You can finally eat and digest more substantial food beyond soups, cereals, and yogurt. Progress is incremental but it’s tangible. You don’t backslide. By month four, you feel a flicker of your capacity to think and create return. You go back to work and are carefully eased back into a new project as a lead. You begin to settle into routine again, the motions of work start exercising the atrophied parts of your creative mind. You make your first painting since you started your diagnosis journey almost six months ago. You get a CT scan–a check-in you’ll need annually from now on–and see that there is no regrowth, no new tumors; you’re healthy! It feels hard to internalize that you are okay, the fear of your health taking a surprise turn for the worse always in the back of your mind. But you are. You got to physical therapy to re-strengthen your gutted core and your back which has been painfully overcompensating for having no useable stomach muscles. You get stronger, little by little. It is slow but it is there, your old abilities within reach.

Everyday you are able to do a little bit more. Its piecemeal progress. A year rushes by and you feel better, unlike any state of self you’ve inhabited before. There is so much to recount and yet it is so little, successive improvements you can’t enumerate but have led you once again into capability. You learn how to cook now that you have a stricter diet and a better appreciation for your body. It takes on a quality of specialness you did not feel for it before. It has endured violence from yourself and others but now it has survived its most lethal challenge yet. It is deserving of more than your rote attention and meager maintenance; it is sacred. You celebrate with food, taking little bites of decadence that would have made you vomit on sight before. You have a lot of sex, relearning how to connect with your body and your partner’s body. As for food so for sex, small cumulative tolerances turn to back into ravenous cravings. Gentleness and pain, ever intertwined. You dance, learning to shift around the meager mass of your new weight. You make more art, tapping into the flow of inspiration after a year of blockage.

The biggest change you feel is connection: a bond to your partner, friends, and remaining family, awed by how they’ve carried you through this when you could barely imagine moving yourself forward. One of the biggest influences on a patient’s recovery, your doctor said, was maintaining a positive mental state and getting emotional support. Patients without any sort of support system to keep their spirits buoyed often had worse outcomes and slower recoveries. As monotonous and purposeless as your suffering felt at the time, it was the first time you’d really let the people who care you demonstrate the whole of their love. Not that they hadn’t before but not like this, all at once. You could never imagine deserving such love or asking for it. Had you been in less dire straits, you would have resisted. “I’m fine,” says the fool, uselessly dedicated to prideful isolation and the lie of self-sufficiency. But that love was always there, waiting for you to accept it. Like sunbeams from a hundred different suns focused through a lens aimed at your heart. It bends through the scar tissue and the nightmares and fills your body with light.