How to Read Dystopian Fiction in Dystopian Times

Senior year of high school, I read 1984 by George Orwell for the second time. It was for an AP Literature class called “Logic and Rhetoric,” to this day one of the best classes I’ve taken. What I remember is analyzing the language in the novel, considering words like “doublethink” and “thoughtcrime” and whether simplifying vocabulary can restrict our capacity for complex thought. It was a revelation, and because of that class, even two decades later, I see Newspeak all around me in political rhetoric, in casual conversation.

It wasn’t my first time encountering dystopian fiction, though. The first time was in fifth grade, when we read The Giver by Lois Lowry. I remember less about that. We had to consider what our own utopian worlds would look like, if we got the chance to build them. We talked about why someone might build a “utopia” like the one in The Giver, and what exactly its system took from people. It was maybe one of the first times I understood what science fiction was— though I wouldn’t have articulated it that way—and we studied the novel with curiosity and a sincere desire for understanding.

When I stepped out into the world with a dystopian novel, I was told something a little different about what dystopian fiction was for. Dystopian fiction is a warning—that was the prevailing opinion. And people asked me what my warning was. What were they supposed to learn from my dystopian world? What was I trying to critique?

For someone fresh out of college, who had only ever studied dystopian fiction in two ways—as a thought exercise that taught me about human nature (The Giver) and as a way of seeing the world around me more clearly (1984)—this was a bit of an odd question. It’s not that I didn’t think dystopian fiction was concerned with the future—I obviously did. It’s more that I had never thought “warning” me about the future was dystopian fiction’s highest priority.

This is a bit of a fine distinction. But George Orwell once said, “1984 was based chiefly on communism, because that is the dominant form of totalitarianism, but I was trying to imagine what communism would be like if it were firmly rooted in the English speaking countries.” The book’s primary concern is Orwell’s present, not his future—his observations of Stalinist government (right down to Big Brother with his big mustache a la Trotsky), and of his own. That doesn’t mean the book can’t also be a warning about the future, but it’s not a step by step guidebook on resisting totalitarianism. It makes us open our eyes to now. It said (and still says, which is why it’s so brilliant), this is already happening. This is what the world is like now.

Lately I’ve been seeing sentiments like “Dystopian fiction failed us” and “what’s the point of dystopian fiction now?” here and there. They’re primarily an expression of grief, and I’m not here to critique them or the people who say them—I understand the sentiment and have felt it myself. For example, last year, Elon Musk shared a graphic on Twitter basically aligning himself with dystopian heroines like Katniss and yes, Tris. That’s right, the world’s wealthiest man thinks of himself as a scrappy teenager fighting against oppression. (Oppression by whom, I wonder, when he’s one of the most powerful people alive and has aligned himself with the people who have total control over our government?) It seems impossible to me that he would believe he’s like the hero of those stories. I saw that graphic and yeah, I for sure felt like I’d failed. But I reminded myself that I can’t control what people take away from their reading. And if he didn’t catch the “you are not the hero of this resistance narrative” vibe from The Hunger Games, well, that’s not because Suzanne Collins wasn’t clear.

If you believe the primary purpose of dystopia is to warn us and steer us, then I guess you’re right—we’ve fallen into all its traps all over again, and it’s not doing its job. I’m not sure I agree, though. I think dystopian fiction’s highest priority is the same as most literature: to express something true about now. It simply does so in an exaggerated way. The “warning” is a side effect of that. But if you believe that now is the genre’s highest priority, rather than the future, it does change whether you think it’s still worth something, whether you think dystopian fiction is “doing its job.”

I recently made a list of dystopian recommendations. Those books exist on a spectrum of “blistering” to “less blistering” in terms of social critique. Some of them were dreamlike, more fable than realistic. Some put the “dystopia” in the background, with a different plot— cat and mouse pursuit, locked room thriller, or even romance—in the foreground. Each of them, without exception, expresses something true about now.

“I wouldn’t call The Seep ‘dystopian’,” someone in Chana Porter’s comments section said (in a nice way). They had a point—The Seep is about the world’s best alien invasion, where the aliens just want us to be happy and at peace, and give us endless possibilities. But the lovely, true thing about The Seep is its gentle exploration of how getting what we want, whenever we want, sucks some of the marrow out of life…and doesn’t spare us from grief. I look around myself now and I see certain parts of our world exhorting me to pursue constant pleasure and to avoid any and all discomfort, and I think about that novella, about the emptiness on the other side of the constant, immediate satisfaction of my needs.

The Dividing Sky by Jill Tew is a dystopian romance. I’ve seen some scornful comments online, not about this book, but about the very idea of “dystopian romance.” I want to encourage people to see that this isn’t an either/or situation— you can’t either have meaningful social critique or romance. It’s a both/and. The Dividing Sky describes a corporate nightmare world where people outsource their meaningful social and emotional connections so that they can increase their productivity, which…listen, that’s a little too familiar, right? And in the midst of this too-real system, two people find each other and fall in love.

“Dystopia” is now. The value of dystopian fiction is in showing you what’s already around you. And you know what else is now? You and your spouse, going on dates. You and your kids, laughing at the dinner table. You and your friends, going to see Superman and discussing David Corenswet’s dimples. You singing along to KPop Demon Hunters’ soundtrack in the car. These stories—these precious stories—also have a place in dystopian fiction. Reading about people falling in love in a dystopia is not me trying to escape my reality. It’s me trying to believe that goodness still exists and is worth fighting for in my right now.

I want to see the world expressed back to me truly— yes. I want to see the capitalist hellscape, the totalitarian hellscape, the technological hellscape, revealed to me in fiction, yes. Because that fiction says, what you see is real. It’s a relief for a book to acknowledge your reality and to communicate to you that it sees what you see.

But let’s not underestimate the power of other stories emerging from that expression of truth. A love story. An adventure. A quiet tale of grief. It’s okay for a book to acknowledge that these smaller, or lighter, or softer stories exist in the midst of hardship. Because those are our stories. Those, too, are our now. And if the job of dystopian fiction is to reveal us to ourselves—a more expansive, inclusive definition of “dystopian fiction”—then there has to be space for that kind of “now,” too.

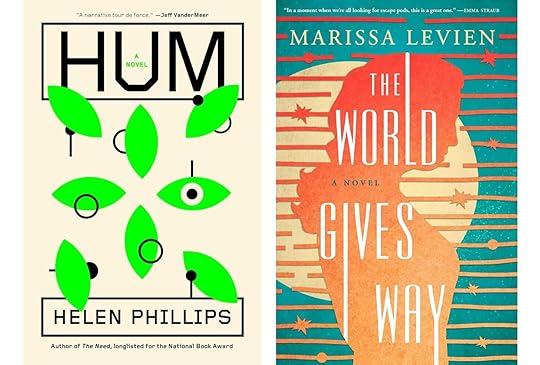

Every book doesn’t have to do everything. That’s why we have so many of them. There’s a place for Hum by Helen Phillips, showcasing the horrors of constant noise and distraction, among other things. There’s a place for The World Gives Way by Marissa Levien, creating a parallel to our collapsing world as it takes you on an adventure. There’s a place for the gentlest shades of dystopia, there only if you squint. There’s a place for mysteries, adventures, and romance. There’s a place for our harrowing Hunger Games and our “what if love was outlawed? what would we lose?” thought exercises. And yeah, there’s a place for Divergent, too. It doesn’t have to do every job that a dystopian book can do, and it doesn’t have to be as solemn and incisive as the most solemn and incisive dystopian books on Earth; I release myself and all other authors from that charge. And I release you, too, from only thinking of this subgenre as a collection of guidebooks that tell you what not to do. That is not the job of fiction.

I’ll finish with a quote from Ursula LeGuin:

I’m not saying fiction is meaningless or useless. Far from it. I believe storytelling is one of the most useful tools we have for achieving meaning: it serves to keep our communities together by asking and saying who we are, and it’s one of the best tools an individual has to find out who I am, what life may ask of me and how I can respond.

But that’s not the same as having a message. The complex meanings of a serious story or novel can be understood only by participation in the language of the story itself. To translate them into a message or reduce them to a sermon distorts, betrays, and destroys them.

This is because a work of art is understood not by the mind only, but by the emotions and by the body itself.

Who are we? We are the highs and the lows, and we are sometimes both at once.

V