The Advent of Nanzeta

Stepping from the noisy street into the almost crowded lobby of Denver’s Albany Hotel, a gentleman has just entered. With a walking stick that he lightly touches to the ground (he’s far too young to require its aid) he crosses the room and presents himself at the counter. He slides two silver dollars toward the clerk and signs his name in the guest register while the clerk eyes him with apparent curiosity—and perhaps, too, some suspicion. His prepayment for the room is meant to earn him some good faith. It’s also meant to allay any too-personal questions. He is here on business—what that business is, for now, is for him alone to know.

The clerk, having selected a key from the wall behind him, now slides the guestbook toward himself and turns it so that he can read it clearly and without effort. And while the man is thus occupied by the letters and names and titles only moments ago scrawled there, the gentleman half-turns and leans against the counter, allowing those who have gathered in the hotel’s reception room to observe him. Everything about him, from his tailor-made Prince Albert suit of buff tan, to his perfectly groomed hair, long and black and hanging to his shoulders, to the large Panama hat with its unusually wide brim, to the jeweled rings he wears upon his delicate and pristinely manicured hands, is intended to make an impression. So far, his efforts appear to have succeeded.

The clerk clears his throat, recalling the gentleman to the business at hand. “A two dollar room,” he observes. Not the best. Far from the worst. “Are you traveling alone, Prince …” the clerk looks at the guest book once more. The name is a remarkable one if not exactly easy to remember—or pronounce.

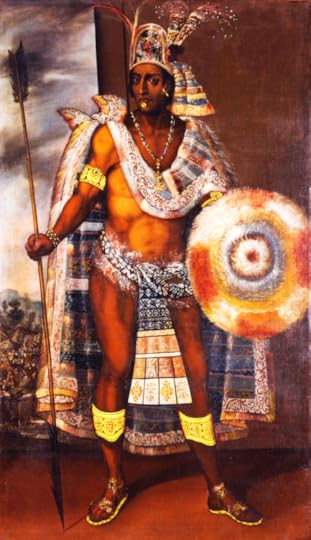

“Prince Nanzetta,” says the gentleman, helping the clerk out and, at the same time, introducing himself. “Prince Nanzetta Pahassnee Montezuma, tzin of Gatamo.” His voice deep and even stands in direct juxtaposition to his elegant, almost feminine features—and his brown skin.

“Tzin?” the clerk inquires cautiously. Is his temerity the product of incredulity or humility in not knowing or understanding the meaning of the title?

Before the young guest can answer, a woman approaches the desk. She leans her bosom against it. Her gray hair is perched upon her head like a bird’s nest and her heavy earrings drag her lobes toward the earth. She looks at him, quickly, like a hen, and sends her jeweled lobes swinging.

“You are a prince?” she asks him. “Prince of what? Of where?”

Her doubt in his claims is quite apparent, but the large and inquiring eyes of her companion, a young woman who, from her place mid-way across the room, is staring at him in want of a satisfactory answer.

He has not yet decided to give one.

“You look like a Mexican, though a well-dressed one at that,” she continues before he can answer her. “And I suppose you are very handsome for all you could be my great grandson.”

He is unruffled. He has nothing to prove to this commoner. At least he is confident in his ability to do it. He turns back to the hotel clerk.

“I will rest until dinner. My room key, please.”

He is handed it.

“I hope the is to your satisfaction,” the clerk says, half-sanctimoniously.

“I will be sure to let you know if it is not,” answers the guest. He turns then, offers the slightest nod to the old woman and a slightly more significant one to the young woman who is still watching him and turns from the lobby in the direction of the staircase. He might take the elevator, but then his ascent would be invisible to the still watching and now captivated crowd.

In his room, the young man rests and he reads—books on Mesoamerican civilizations and explorations into the remote and forbidden regions of Asia. In time, a card is presented at his door, and then another and another. Denver’s genteel class, having heard of the mysterious stranger’s arrival, have come to dine at the hotel’s restaurant and to have a look for themselves at this so-called “prince” of the Aztecs. He will not dine alone tonight. He will eat the best that the hotel has to offer, and he will do it amidst the best company the city can muster. The prince accepts these invitations and sends a message to the front desk. Tonight the common table will be set in preparation for a royal dinner.

After he has bathed and dressed, has combed his hair to a sleek shine, and has dressed again in the garb of a royal exile, replete with jeweled rings and a diamond incrusted horseshoe pin which he wears high upon his cravat and with the heel end downward. Why save up good luck when you could benefit by it today, after all? He examines himself once more in the mirror and finding his reflection satisfactory, he leaves his room for the dining room. He is not the first to arrive there, but neither is he last. He takes his place, not at the head of the table but at the center of it. He may be a royal, but he is a democratic one, preferring the company of the middle and upper middle classes to those of the elite, in the United States or anywhere—and so he will later tell them. He makes a mental note to do so, but the script is so well memorized by now that it requires little in the way of remembering. He, Nanzetta, is the prince of Montezuma. What is there to remember?

At the table, where a few have been seated already, others arrive, and soon there will more than the table can comfortably hold. If the reception room is not filled to standing-room-only it is not filled, such is his motto.

The prince orders the boiled tongue with chili sauce, and he eats as the Continentals do, with fork in the left hand and knife in the right, not because it is what he has become used to as a royal, or as a result of his many and varied travels around the world, but because it shows off his jewels—and his hands—to best effect.

All eyes are watching him, some directly and studiously, others more surreptitiously. The questions begin, though they are innocent enough at first. How does he like Denver? How long does he intend to stay? What is it that has brought him here?

He is, just at first, evasive, paying more attention to his meal than he is to his companions, and yet eating carefully, slowly, cutting small bites and chewing them thoughtfully.

More gather and the table fills. Among the guests is the woman with a birds nest for hair and her young charge. Standing nearby but apart, not seated, not here to eat but to do their work with pencils and paper are four or five newspapermen ready and eager to share the news of the prince guest with the citizens of Denver and his riveting history, too.

They are soon so eager for his story, that one of them asks him outright.

“What gives, Prince? What is your story, anyhow?”

“Yes, tell us,” another chimes in. “Where are you from, and what has brought you here?”

“Oh, please, tell us about the land you are to inherit?”

This last from a pretty young woman who bats her eyelashes at him and blushes ferociously. It is a request he cannot not resist, and so he clears his throat and begins his romantic tale.

“I have come to this city on business,” the prince begins in perfect English only delicately laced with a Spanish accent. He will not say just what the business is that has brought him. Not yet. “And I have come here by way of a long journey, wherein I have visited many countries and have sought to educate and inform myself on the ways of the world. Most recently I have visited the Pacific cities from Washington to California. But my home,” he says, taking on a decidedly more melancholy tone, “is located in the southwest portion of Mexico in a small independency just north of the Yucatan known for centuries as the Sacred City of Tenochtitlan.” The exotic name is not an unfamiliar one, but its mystery and remoteness serve his aims perfectly. His audience is mesmerized, and he has only just begun. “I am a descendant, the last, even, of the great Montezuma, and one day I will inherit the city and my rightful place as ruler of the people there, the remnant of Aztecs whom Cortez sought to destroy.” He paints the picture. “Tenocthitlan is located in a fertile valley 180 miles long, surrounded on all sides by rocky gorges, and death-inviting morasses and further fortified by a wall which no alien race has successfully penetrated.

“There are some 80,000 of us who live in the Sacred City,” the prince continues after taking a moment to delicately sample his food. “That is all that is left of the great nation that once numbered 80,000,000. Cortez thought he’d vanquished us all, but it was not so. And now, …” the prince pauses for dramatic effect. “What Cortez failed to finish, President Diaz of Mexico is determined to do.

“Between our land and that of Mexico is a stretch of neutral desert inhabited by the Yaqui Indians,” the prince continued. He takes a sip of his drink and slowly sets it down, thoughtfully “recalling” his home and the story of his people. “The Yaqui are poor and have been kept in a state of oppression by the Mexican government. They are said to be fierce savages who have no desire but to murder and plunder, but such is not uniformly the case, and when it is, it is due to the state of desperation in which the Mexican government maintains them. The Yaqui, desperate for reprieve, came to find sanctuary in the neutral lands, but the Mexican government, determined as they were to keep the Yaqui under their thumb, followed them and entered the neutral territory. There, the soldiers committed such atrocities upon the tribe that our people offered to help them. My uncle was placed in charge of a small but determined army of Yaqui. I loved my uncle dearly, for he had sent me to California to be educated, and so, to repay him and demonstrate my love and devotion to him, I begged him to allow me to accompany him. I was young then,” the prince says and pauses to gauge the audience’s response to this. He dares someone—anyone—to comment upon how young he looks now, how impossible it seems for him to have accomplished so much at such an apparently young age, but no one does. “Having returned home to these newly arisen difficulties,” the prince continues, “my blood was full of a sense of duty, but it was full, too, of youthful vigor and naivete’. I wanted to show my uncle that I was prepared to earn my inheritance, that I would become great like my father and like the Aztec kings before him. He granted my request, and together we marched northward, my uncle, myself, and a hundred strong Yaqui soldiers.

“Upon arriving in Mexico City, my uncle, accompanied by six brave warriors, determined to find the leader of the Mexican army and reason with him or die trying, I was left to stand guard, and thus I did. The meeting lasted hours, then days, and as I kept my vigil, I happened to meet a daughter of one of the senior officials as she came and went providing refreshment to her father and his brethren in arms. Our brief conversations turned into flirtation, and soon I found myself earnestly wooing her. We fell in love, but I knew my family would not approve of my marrying so far beneath me.

The meeting ended, and I was called away. I expressed my desire to my uncle and then to my father, but I could not persuade them to support my desires. I tried to give it up, to devote myself to the duties before me, but then I learned that of the evil deeds of one of the Mexican soldiers who had lured her away from the city center posing as myself, and there he had made his own case. She refused him. Incensed by her refusal, he murdered her! Fury filled my heart upon hearing this grim news, and I swore to vanquish her assailant!

The prince allowed himself a pause here to collect himself and to provide the emotional evidence that would guarantee his story was felt. He laid his hands upon the tablecloth and, closing his eyes, he took a few steadying breaths.

“I was soon gratified,” the prince continued at last, “to see that the bond between myself and my brothers, the Yaqui, was made strong by my service to them, and as I had so faithfully carried their cause, so too were they prepared to adopt mine. And so a small band of us—I quite consider myself one of them now—ventured out on a mission of revenge. I returned to Mexico City, and sought the villain out, but upon hearing of my pursuit of him, he fled the city. I followed him from place to place. At last in the southern part of Mexico, I caught up with him, and the meeting resulted in a vicious duel. The officer was not as skilled with the knife as was I, and so, to hedge his bets, he had armed himself secretly with a pistol. He fought bravely, but he was no match for my quickness and skill. When it seemed certain that I would win the struggle, he pulled out his gun and took a shot, grazing me in the temple.”

For the sake of his wide-eyed audience, the prince stops a moment here, and with two bejeweled fingers he pulls aside a gleaming tress of long black hair, like a curtain over a precious work of art, and displays the proof of his injury by way of a long, shiny scar on the side of his head.

“The gun must have been a last minute thought of the soldier,” the prince continues, “for there was but one bullet loaded, and so he threw it aside and returned to the use of his knife as a weapon (whether I was gentleman to let him retrieve it or fool, I’ll let you decide) and so the struggle continued. I managed, in the end, to win,” he says and pauses to exhale a breath of reminiscent exhaustion, “but not before suffering a deep gash to my wrist.” Again, he offers a scar for consideration.) “And a nearly fatal wound to my side.” The prince pauses once more, but the revealing of once-injured flesh has come to an end. His piercing black eyes stare blankly at a spot on the table. He shakes his head slowly as he recalls the words of his story more than the scene itself.

‘To answer for the murder of the soldier,” he begins again, though slowly, dramatically … “a bounty was placed on my head. And so I fled for the U.S. border. I was nearly caught on several occasions, but at last I reached Austin. And there, in a hospital, I collapsed and there remained on the very bring of death for many weeks. I was nearly recovered when I fell ill again, and I was not wholly recovered from that when I left the hospital for fear of my life, for by then the bounty hunters had learned where I was and had come to find me.”

The prince scans the crowd then. Should he continue? He could, for he has more of his story to unwind to a ready audience, but he sees that not everyone believes him quite completely. The story is too wild, too tall to be bought wholesale by everyone. The pretty young lady across from him looks as if she is prepared to (or perhaps she has already) shed a tear for the poor, unfortunate prince. He offers her a smile of gratitude. With his full lips and round face free of even the hint of stubble, he does appear much younger than he actually is (though not as much younger as he pretends for the sake of the necessary experience his story—and his occupation—requires). But he is handsome—“a striking figure”, the papers are wont to report—and he knows his power to leave an impression upon the impressionable. He decides that enough is enough for one night, and so provides the necessary close to this chapter of his tale.

“So long as there is a bounty on my head,” he concludes, “there is no chance of my returning home. There is but one path to the Sacred City, and the soldiers of the Mexican army guard its entrance carefully. Until there is a change in government, I am a lonely exile, a prince without a country, and a homeless, wandering wretch.”

He places his napkin on the table, and exhaling in punctuation to his sorrows, he hales the waiter … but, and as planned, he finds he is not allowed to pay for his dinner, nor for his room for the remainder of his stay. The money, more money than is required, is offered as a stipend toward remunerating the poor prince for his difficulties. He will sleep more peacefully tonight, it is hoped, for knowing he has friends in this, his adopted home, for as long as he wishes to remain, a night or two or three… Not longer. No, not longer.

But what could he give them in return? Why, he had already given it by way of the honor of sitting in company of a prince for a few hours. An honest-to-goodness prince! Were they not just a little more royal for having sat in the presence of royalty?

He rises from his place at the table and offers his heartfelt gratitude for the generosity of his new friends. Just as he is about to quit the room to retire to his own, he turns, and, almost as an afterthought, offers an invitation.

“In the event you are interested,” he begins and pauses for dramatic affect … “tomorrow, on the square before the courthouse, I will be telling a little more of my story, of my adventures, and sharing some of the wisdom I have learned both in my education at Stanford and in my life among the Yaqui, for they have truly taught me more than any university could do. And the skills I have mentioned, those which kept me alive, and those which provide me bread in this chapter of my life, I will have on display. Do, my friends, consider coming to see me there.”

The audience, some of them, a good few, appear receptive to this invitation. The pretty young woman is blushing and blinking and fanning herself. Her guardian, the woman with the bird’s next for hair, appears less convinced but, to his great pleasure, not entirely opposed.

He bows then and turns from the room.

The next morning, Prince Nanzeta’s courtiers found him, mounted upon a box and extoling the virtues of some elixir he swore could and would, he guaranteed it, heal any ill.

In glowing words he told how such a one had been cured even when the undertaker had been telephoned for to take his measure. He said that the medicine would not fail, being based on such a principle that but one minute portion was enough to make Ponce De Leon shed tears of sorrow that it had fallen to the lot of another to discover the fountain of eternal growth. He expatiated so largely upon its merits that a few were induced to buy.

Men and women of the crowd began to buy, and as they parted with their one dollar bills, the next and superior cure was produced so that they traded the one in for the next until, at last, he sold out. Some of his audience from the night before, the young woman and, perhaps, even her elderly guardian, were induced to buy. The man was a student of medicine, after all, and an apprentice of the Yaqui medicine men. Why should he not make his way in this world by the knowledge he had gained?

Still others, upon seeing this lowly and pathetic display, were either woken from their dream or validated in their suspicion that the man was a fraud. Either way, Prince Nanzeta cleaned up, and, having sold out, he packed up his things and moved on. The next stop? Galveston, Texas, where the story, with a little help from a friend, begins to fall apart.