1902

In the spring of 1902, the character which would become known as Prince Nanzeta[1] appears to have arrived fully formed in Denver, Colorado. Undoubtedly it was a practiced part and had been played many times before, but for whatever reason, the occasion of a Mexican prince’s arrival in a Denver hotel seemed a significant one. Many believed his story. Others understood him to be an impostor, but they watched and listened and played along with the charade, nevertheless. The young prince, at least on this first occasion, took his audience’s doubt in stride and subsequently played to their weaknesses. His story was a sad one, his plight filled with tragedy and survival against all odds. He was charming, elegant, convincing, utterly unruffled by accusations of an ulterior motive, completely mesmerizing, “strikingly handsome,” and, at the very least, seemingly harmless. And in the days before television and radio, he was an entertaining and welcome distraction.

No fewer than four Denver newspapers reported on the young “prince’s” arrival, upon his claims of nobility and his story of exile, love and heartbreak, chivalry and death-defying duels, bounty hunters, and his lonely wanderings after being exiled from his home and the land of his inheritance. The story then spread by train and by telegraph, and by the time Prince Nanzetta arrived in Montana, six months later, reports of him had been published from coast to coast. One article which ran repeatedly over the course of three years appeared in more than seventy papers nationwide.

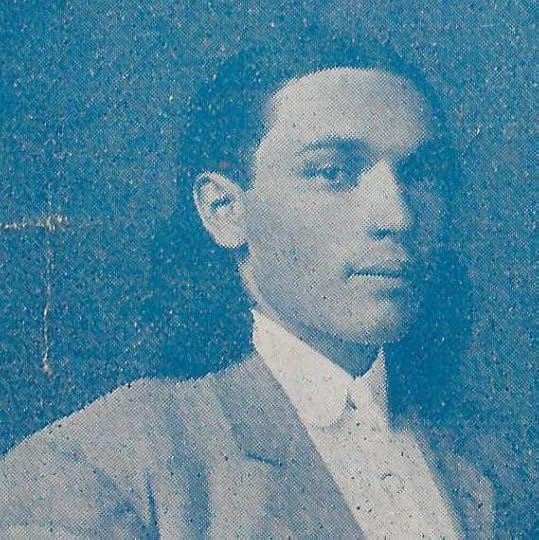

The first accounts of him were consistent in their description of the man who might easily be mistaken for a woman, with his fine features, his diminutive stature, and his small hands and feet. One account even described him as frail. Certainly, no description of him failed to mention his long and lustrous black hair which fell in waves to his shoulders. Those who reported on his arrival in Denver, and then later in Omaha, Butte, and Salt Lake City described him as a dapper, dark-skinned Mexican youth with a mysterious air of suavity who possessed piercing eyes. In his tailor-made (made to fit) Prince Albert suit of tan and a wide brimmed hat, he presented himself as a “well-dressed Mexican”. As an accessory, he carried with him an intricately carved cane, and he held onto it with fingers that were weighted down by several rings of large and apparently authentic jewels—diamonds, rubies, emeralds, opals, and pearls. He spoke with a “charming voice” of “beautiful English, bearing only the slightest accent”, which, together with his “aristocratic features” left quite an impression.

As to his age, there was some variance in the accounts. He was sometimes twenty-three, at other times a year older or younger. Once in 1902, he claimed he was twenty-five. The Paducah Sun reported in August of 1902 in regard to his arrival in Spokane, that “[T]he young man is said to be some thirty years of age, but his looks belie that statement and fifteen would come nearer what he appears.” Indeed, his appearance of youth seems to have been an obstacle between himself and his aims (and his claims) for the first several years of his career as a seller of remedies.

The accomplishments he claimed to have acquired during those years was impressive—perhaps too impressive. Apart from the skills necessary to tell his wild and fantastic story (specifically, the skills of being a famous duelist, proficient with a knife and a pistol, and a world traveler who had seen some 39 countries) he had been educated in both law and medicine at Stanford, spoke several languages fluently, he was an expert ping-pong player and virtuoso violinist. On one occasion he boasted of having established a hospital for Mexican exiles in Salt Lake City. Of his many claims, one, at least, is true: he was a talented and convincing actor.

As an actor, he was perhaps unparalleled in the world of medicine shows and quack cure pitchmen. Unlike other medicine men who either sold their wares as an extension of their exaggerated but otherwise ordinary selves or, in contrast, those who donned a temporary costume for their street or tent performances, Nanzetta became his act. Perhaps he believed it or grew to believe it. Or, just possibly, a portion of it was true enough that the rest was simply a fanciful elaboration. Certainly, it was much easier to convince your audience to believe your story if you, at least in part, believe it yourself—as he appears to have done. His coolness under examination and his quiet and elegant manner, at least as it was described by eyewitnesses, belies a regalness, at the very least an intelligence, that is difficult to fake.

Of the dozens of newspaper accounts that describe Nanzetta’s early appearances, there is an almost consistent through-line. The descriptions, hardly of an everyday average person on the street, all seem to perfectly describe the Nanzetta of Danville, Virginia. Though the tale he weaves in those early months appears to grow and evolve, it’s impossible to know which of the details is merely an example of something more added by one reporter than another and what is truly a newly invented chapter of the “prince’s” story. By August, a few conflicting details begin to enter the picture, his name changes in spelling (though whether that is an intentional deviation by Nanzetta himself or simply an error of reporting, it’s impossible to say) and the Inca people are referenced, sometimes in addition to and sometimes in replacement of, Aztec. It’s shortly after this that things begin to break down and the “Prince of the Aztecs” narrative begins to fall apart. Before we pick apart his story, however, we must first lay down its foundational elements.

What follows is a dramatized account of the prince’s arrival in Denver on the 27th of April, 1902, pieced together from the more than thirty newspaper articles which reported on “Prince Nanzeta” and his travels through the Southwest in spring through autumn of that year.

[1] When he first appeared as an Aztec prince in 1902, and for several years thereafter, the spelling of Nanzetta’s name was inconsistent. Eventually, there was a splitting off of the Prince Nanzeta identity from the one of Dr. Nanzetta, and so, when I refer to the “Prince Nanzeta” character, I will use one “t”.