Boat Trip Through History: Imhotep and the Step Pyramid at Sakkara

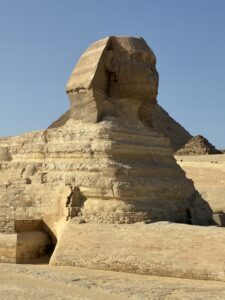

Day two in Egypt: The stepped pyramid at Sakkara, the Great Pyramid at Giza, and the Sphinx. (Plus some tombs with amazing wall paintings and a close encounter with a camel)

I don’t have much to say about the Great Pyramid or the Sphinx. My takeaway was that the Great Pyramid is more imposing in real life and the Sphinx less so.[1]

The Step Pyramid is another story. Or more accurately, it has a story attached to it.

Most architects of the ancient world remain anonymous. We are more apt to know the name of the king who ordered a building than the man who designed it. In ancient Mesopotamia, for instance, kings had their names impressed in the brick used in the great buildings they commissioned. The first architect whose name was recorded was an Egyptian, Imhotep, the man who designed the Step Pyramid at Sakkara.

Egypt’s first major monuments, built during the First and Second Dynasties (3200-2780 BCE), were mud-brick tombs known as mastabas. Mastabas were rectangular structures with sides that sloped inward toward a flat top, built above burial chambers cut through the desert sand and into the bedrock below. Each tomb contained a chapel that held offerings for the deceased to use in the afterlife and a secret room where a statue of the deceased was stored. The interiors of the mastabas themselves were little more than narrow corridors surrounded by a solid core of rubble

In 2780 BCE, the Pharaoh Zoser founded a new dynasty and a new era of Egyptian history: the Old Kingdom, possibly the most brilliant period in pharaonic Egypt. When the time came for him to plan his funeral monument, he wanted something larger and grander than the mastabas of his predecessors. He turned to Imhotep, his chief officer and vizier, to build it for him. Imhotep took the basic form of the mastaba and transformed it something new and thrilling.[2]

Zoser’s Step Pyramid is generally considered to be the beginning of true stone architecture. It is the first building known to have been constructed with stones shaped into precise rectangular blocks. In earlier stone walls, the shape of each stone can be separately identified; Zoser’s pyramid was built with limestone blocks that were carefully fitted together with minimal joints into a smooth continuous surface. The Step Pyramid itself can be seen as a stack of stone mastabas: six immense tiers tower 200 feet high over the granite-lined burial shaft beneath it. It was more like a Mesopotamian ziggurat in shape than the classic Egyptian pyramid.

The shape was new, but many of the details were familiar. In creating Zoser’s pyramid, Egyptian builders, under Imhotep’s direction, took designs, details, and techniques previously used in buildings made from wood, reed, and mud brick and rendered them in stone. They set stone blocks in the same mortar pattern they had previously used for brick buildings. They copied the bundles of papyrus reeds that gave added strength to mud brick walls, creating engaged stone columns–one of later architecture’s basic components. The shaft of each column imitated the plant’s triangular stem. The capital at the top of each shaft was shaped like the open cluster of papyrus flowers or a lotus leaf.

In recognition of his achievements, Zoser gave Imhotep an honor no artist had received before him: a place in history. At Zoser’s order, Imhotep’s name and titles, including “chief of sculptors,” were carved on the base of a statue of the pharaoh.

In addition to being an innovative architect, Imhotep was a scholar, priest, astrologer, magician, and physician. His skill as both an architect and a physician led him to be recognized as a deity. During his lifetime, he was named the son of Ptah, the patron god of craftsmen who created the universe. Two hundred years after his death, Imhotep was worshiped as the god of medicine in Egypt and in Greece, where he was identified with the Greek god of medicine, Aesculapius.

Image of Imhotep from the 5th century BCE. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

[1] You’ll have to take my word for it. The impact doesn’t come through in my photographs.

[2] With the help of who knows how many hundreds of thousands of hard-working laborers sweating in the heat and dust. According to Herodotus, it took 100,000 men working in three-month shifts twenty years to complete the Great Pyramid at Giza (ca. 2550 BCE). Since he was writing 2000 years after the fact, we have to take the number with a pyramid-sized grain of salt.