Polarities, asymmetries, and why we do what we do

[Published first on LinkedIn here]

On Friday last week, I led a nearly three-hour seminar (a recording will follow I’m told) by invitation of the Operations Research (OR) Society and Hull University’s Centre for System Studies. I based it on my keynote, Introducing the Deliberately Adaptive Organisation [1], which is in turn based on my fifth and most recent book, Wholehearted [2]. This time though, I added a preamble and an open discussion that owed more to my fourth book, Organizing Conversations [3], and just as I hoped, it had a profound effect on the seminar as a whole.

Some rough polarities…Here is that preamble’s key slide:

Introducing those polarities (extremes, perhaps on a spectrum, perhaps interdependent, perhaps paradoxically so) in the form of rhetorical questions, it may seem that I’m trading in platitudes or false dichotomies, but there is a much more serious and practical point to be made. But first that more shallow treatment, where the “we” in question refers to practitioners of things systems-related:

Do we see it as our job to design better systems, or instead to engage with organisations as they are, and to help others do the same?Do we see ourselves as conducting research, analysis, or diagnosis, or instead as stimulating dialogue, inquiry, and generative conversations – solutions emerging from those?Are we trying to document a single, authoritative perspective, or instead to give voice to multiple, diverse, and perhaps conflicting perspectives?And following on from that last one, are we drawn to what can easily be formalised and perhaps visualised, or instead to actual experiences and their differences and ambiguities?Are we documenting the organisation as though frozen in time, or engaging with the experience of change – relationships and structures of various kinds continuously and emergently forming, dissolving, and re-forming out of what I referred to tongue-in-cheek as the “quantum foam of organisation”?Are we looking for problems to solve, or helping the organisation to meet its challenges well [4]?Are we designing solutions, or helping people and/or organisations to make meaningful progress?Clarifying that previous one, is our motivation instrumental (e.g. to achieve some efficiency or performance improvement) or to emancipatory, referring to human conditions, freedoms, etcAre we imposing perspectives and/or solutions (predetermined or otherwise) on people, or is the process not only invitational and participatory, but authentically so?Even after allowing a time of divergence, do we feel driven to converge on a limited number of key concepts, problems, and interventions, or are we about enabling progress on a broad front?To that last point in particular, I had a couple of different things in mind. First and most obviously, there is, after Kaner [5], the classic diverge-converge pattern of facilitated decision making, with its central “groan zone” of maximum divergence. One of the reasons that Organizing Conversations took me two and half years to write – much to not only its own betterment but Wholehearted‘s too – is that editor Gervase Bushe took me to task whenever he thought I was promoting convergence unnecessarily. I ended up adding a whole chapter on calibration, making explicit the range of choices between convergence and divergence the host or facilitator has in the design and conduct of participatory experiences. That line of thinking carries over into Wholehearted, making its treatment of the Viable System Model decidely non-traditional both philosophically and practically.

Talking of philosophy, the second issue I had fresh in mind was prompted by my recent reading of John Mingers, Systems Thinking, Critical Realism and Philosophy [6]. The critical realism aspect of this book was fascinating, but I wish that in its treatment of systems thinking, it had been more critical! I did a double take when he went straight from the existence, study, and hypothesising of the (real) causal mechanisms that shape the (actual) events and non-events that we are able to observe, to the apparent necessity of systems thinkers to draw boundaries around things at the earliest possible opportunity. In such a book, and especially given the book’s own discussions about the significant difficulties of boundary identification, this illogical and unquestioned non-sequitur was surprising, to put it mildly.

And their asymmetries (or one asymmetry in particular)One way I could weasel out of false dichotomy mode would be to steal a trick from the Agile manifesto: While we value the things on the left, we value the things on the right more. Not to comment on the Agile Manifesto but its derivatives, its “this over that” style has been done to death already, and it’s too easy to fall not only into cliché but platitude that way.

The issue and the asymmetry goes as follows. On the one hand, doing the things on the right gives the things on the left (assuming you need to do them at all) more material to work with. That may seem like harder work, but it increases your chances of hitting on something important, and if you really must converge on a smaller set of things to focus on, that’s easily done. On the other hand, doing the things on the left may exclude important possibilities in ways that aren’t nearly so easily fixed later in the process. When the damage is done, it’s done.

For example:

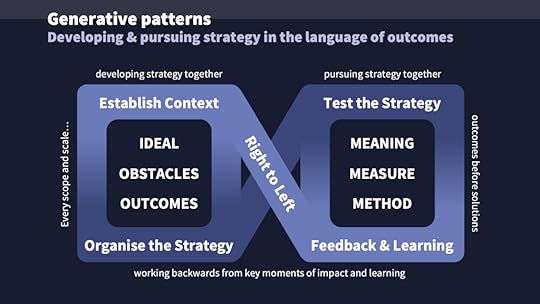

A “design better systems” framing may – even if unintentionally – seem to exclude more evolutionary approaches from the outsetResearch, analysis, and diagnosis often serve to delay conversations that could easily happen very much closer to the start of the process, and when they do happen, they’re now about what that work has produced. The reverse is not true; dialogue does not have to time-consuming.A single, authoritative, and easily formalised perspective (a process diagram, for example) glosses over difference, and once again, it shifts the focus from actual experience to model, from territory to map.A frozen-in-time model of the organisation fails to capture what is gained and lost in the process of change (self-organised or otherwise), a key consideration if the organisation in question aspires to adaptability. There is also a real issue of scalability; in his writings on the Viable System Model, for example, Stafford Beer himself warns that there may be (and this is not his word but his emphasis too) thousands of things to analyse, and is it then even remotely possible to keep up in the presence of even modest amounts of flux?Framings of problem solving and solution implementation are by definition unhelpful if the challenge is in any sense adaptive – i.e. one with a propensity to change itself and/or us in the process of our engaging with it, which covers many if not most challenges not only in the social sphere but in product development also. Conversely, “meeting our challenges well” has a generative quality, and may help to inspire even where technical solutions are available. And what is our job if it is not to help people “make meaningful progress”? (To be fair that’s a whole topic in itself, but have a play with that framing, one long known to work well in the product sphere [7])With regard to instrumental vs emancipatory (if I can put it like that), history shows that the two can often go hand in hand. But let’s not leave the human dimension looking like an afterthought – once the damage is done, it’s hard to recoverOn the imposed vs invitational / participatory axis, are we using well-intentioned ends to justify inappropriate or inauthentic means? How long until so-called participants see through the contradiction?Coherent by constructionIf by this point you’re feeling uncomfortable, perhaps you’re thinking that a push to the things on the right just turns everything into an undifferentiated mess. Not so! With the generative patterns (see figure below) of Organizing Conversations (and before that, Agendashift [8] and the Agendashift Academy’s Leading with Outcomes leadership development programme [9]), the process is best understood as one of exploring a multi-dimensional space of possibility. With step representing a change of direction/dimension, the conversational threads that describe experiences, concepts, and new ideas get carried over, dropped, or picked up again naturally without the need for any forced convergence. At the end of the process, everything that has been produced is easily traceable back to its origins. Not random ideas then, but an organisational strategy that is coherent by construction, anchored in reality (I’ll say in passing that this happens to be the most rigorous part of the process), and yet full of possibility.

What it means to be a practitioner (or to choose one)

What it means to be a practitioner (or to choose one)If your discomfort remains, I hear you. Returning to that first slide, my aim here was not to condemn the things on the left and their respective practices; in their rightful places, they’re all useful – essential even. But if you consider yourself a practitioner, do yourself a favour: see how long you can postpone them, and push yourself to keep working on that.

And yes, you’re constrained by the expectations of your engagement, so let’s address that elephant too. To those on the buy side looking to engage a practitioner of some kind, think seriously about your organisation “meeting its challenges well” and “making meaningful progress”. Then reflect on what it would feel like for both of those to be sustained over time and into the future – a future not only of uncertainty and challenge but of possibility too. What kind of help and what kind of engagement do you then need? This may be your opportunity to turn a tactical choice into a more strategic one.

Acknowledgements and referencesThank you to Matt Lloyd PLY, Gemma Smith, Roberto Palacios-Rodriguez, and Mandy Stirling of The OR Society for Friday’s seminar invitation, and to Kert D. Peterson, CST, AKT for comments on earlier drafts of this article. Some of this ground was also covered in a panel session earlier last week with Philippe Guenet and Jen Le Marinel at the invitation of Kirsty Knowles, PCC, Senior Prac. and Jessi Dent of the International Coaching Federation (UK ICF). Recordings of both events are due to be published, and I’ll add them to the our media page once they’re available.

[1] Introducing the Deliberately Adaptive Organisation (agendashift.com/keynotes)

[2] Mike Burrows, Wholehearted: Engaging with Complexity in the Deliberately Adaptive Organisation (2025, Agendashift Press)

[3] Mike Burrows, Organizing Conversations: Preparing groups to take on adaptive challenges (2024, BMI Series in Dialogic Organization Development)

[4] Nora Bateson, Combining (2023, Triarchy Press)

[5] Kaner, Facilitator’s Guide to Participatory Decision-Making (3rd edition, 2014, Jossey-Bass Business & Management). The 1st edition was published in 1996.

[6] John Mingers, Systems Thinking, Critical Realism and Philosophy: A Confluence of Ideas (2014, Routledge Critical Realism)

[7] Bob Moesta & Greg Engle, Demand-Side Sales 101: Stop Selling and Help Your Customers Make Progress (2020)

[8] Mike Burrows, Agendashift: Outcome-oriented change and continuous transformation (2019)

[9] Leading with Outcomes (academy.agendashift.com)