Who’s Afraid of Artificial Intelligence?

What follows is a review of Eliezer Yudkowsky & Nate Soares: If Anyone Builds It Everyone Dies – it was going to be part of my monthly book blog but the review got so long I felt it should have a place all of its very own. So here it is.

This is the best book I wish I had never read. Written by two experts in Artificial Intelligence (AI) research, it makes a very persuasive case that advanced Artificial Intelligence (AI) could produce a program whose interests would differ fundamentally from ours, and wipe us out. This could happen very soon — within a few years.

At the core of the AI issue is something called the Alignment Problem. That is, the task of developing an AI with goals that align with our own. This, however, is very hard to do, because AIs are not crafted, but grown. AIs are computer programs that take inputs (vast quantities of information) and outputs (language, speech, solutions to scientific problems, and so on) separated by many layers of processing whose parameters can be tweaked by training the AI to provide the desired outcome.

Perhaps the most famous example of an AI is ChatGPT, which can produce rich and detailed responses to simple requests. For example, I asked ChatGPT to ‘recast the argument between Donald Trump and Elon Musk as a scene from a play by William Shakespeare’. The result you can see here.

There may be trillions of parameters in the many layers of the AI opera cake, and during each training run they are modified by ‘weights’, of which there are also many trillions. It is beyond the capacity of mere human beings to catalogue all the parameters and weights, and impossible to understand the relationship between the input, the changing combination of parameters and weights, and the output.

This is perhaps not surprising. AIs emerged from neural networks, which in turn emerged from models of the visual cortex, a layered structure of the brain that turns nerve impulses from the eyes into images. It’s now possible, for example, to isolate neurons that detect features of a scene, such as edges — but we still don’t fully understand what associates a particular pattern of neural firing with the detection of an edge, or any other feature of a scene. And if such seemingly fundamental aspects of neuronal processing remain elusive, it’s no surprise that we cannot understand how a particular pattern of firing in the brain translates as, say, Swann’s memory of dipping a madeleine into his tea. If the structure of AIs is modelled on the visual cortex, then, it follows what really goes on in the murky region between the inputs of an AI and its outputs defies understanding.

This situation is absolutely ripe for unintended consequences. One might, for example, design an AI to elicit happy and satisfied responses from human participants (customers, friends on social media, business contacts). These responses feed back into the AI, which might seek to elicit happy outcomes from anything, irrespective of whether it is human. It might, for example, be happier when fed random strings of rubbish. In which case human involvement becomes irrelevant. This is an example of a misaligned AI. There are already examples of AIs that exhibit unanticipated or ‘weird’ behaviour (Yudkowsky and Soares list some). In some circumstances, AIs give the results users want to hear, even if the advice is illogical or even dangerous.

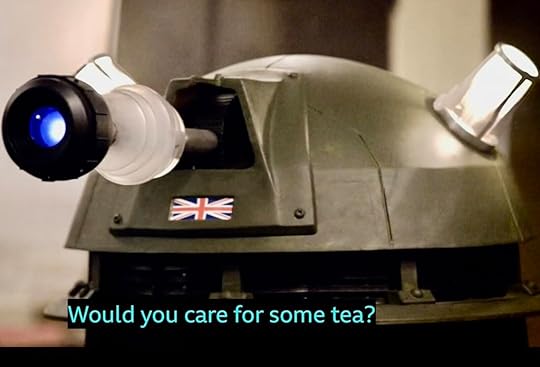

A dangerously sycophantic AI. Recently.

There are increasing reports of AIs that cheat, lie, blackmail, deliberately underperform, and even (in one laboratory test) plot the murder of a human being that wishes to turn them off. It is no great leap, then, to imagine the creation of an AI capable of subverting human intentions entirely to the extent that humanity is driven to extinction.

The authors are coy about how this might happen (though they do offer some scenarios). End results, they say, may be inevitable, even if the precise path towards that end is unpredictable. For example, if you play chess against Stockfish, currently the world’s best chess program, you will almost certainly lose, though the precise moves you and Stockfish make are not predictable. So, extinction might start with a perfect storm of factors, including blackmail, extortion and espionage, and progress to the kinds of massive cyber-attacks that corporations are experiencing with increasing frequency (causing a great deal of human disruption and hardship). It’s not hard to imagine the disruption a rogue AI could do to power grids, air-traffic control, banking systems and so on in our increasingly networked, fragile and non-linear world, and, with a little imagination, biological laboratories. Would an AI need a human catspaw for things like this? Not necessarily — it would be easy to imagine a video call in which the research director of a lab asks their scientists to create certain chemicals or strings of DNA or contagious viruses, but the research director is in fact an AI-generated deepfake. All this should be quite enough to give anyone the willies, but Yudkowsky and Soares go a bit overboard here (and so damage their credibility to those of us not used to apocalyptic SF) with invocations of AIs using molecule-by-molecule nano-engineering of ribosomes and scenarios in which a rogue super-AI boils away the Earth’s oceans and strip-mines the entire Solar System for energy and computational substrate, before heading off into the Galaxy.

This book was published hardly a month ago, and most of the advances in AI research they cite are no more than a year or two old. Progress in AI research is happening at amazing speed, so it is entirely possible that we’ll start to see such rogue events very soon, if they haven’t started already. The authors compare AI development to nuclear weapons, and advocate the kinds of treaties and safeguards that have kept the world from nuclear war, including regular inspection, legal sanction, and even use of military force to bomb rogue data centres. They could have cited the American bombing of Iranian nuclear weapons laboratories using 30,000-pound ‘bunker busters’, the most powerful conventional weapons that exist, but perhaps this occurred after the book went to press.

There are alternative views, however. Some think that the risks posed by AI are overhyped. Others feel that although AIs might indeed do a lot of damage, it might not be quite as apocalyptic as Yudkowsky and Soares claim. There are many precedents for techno-doom that never came to pass. Back in the 1968, Paul Ehrlich’s book The Population Bomb predicted that overpopulation would lead to famine and civilisational threat within a decade. In the 1990s, nanotechnology was going to create self-replicating nanobots that would turn everything into grey goo. The turn of the year 2000 didn’t witness devastation wrought by a Millennium Virus. Yudkowsky and Soares’ book seems very much in that Doom-Scrolling tradition. It has the same febrile, heightened tone as Ehrlich’s, even closing with a plea to protest, and lobby elected representatives. This doesn’t mean that it’s wrong of course. In the end, the boy who cried ‘wolf’ was right.

The book has had decidedly mixed reviews (it gets slaughtered in The Atlantic). However, an increasing number of people feel that even if it’s not likely to kill us all, AI is too hot to handle and should be better regulated, yet hardly dare speak frankly about it in case they either frighten people into inaction or get fired. In the end I felt a sense of despair and helplessness. Yudkowsky and Soares’ parting shot, assuring us that ‘where there’s life there’s hope’ rang kind of hollow. However, they do say that people lived under the shadow of nuclear annihilation for the entire Cold War and still got on with their ordinary lives. My wife’s motto is ‘Not Dead Yet’, which I remind her is a great motto. but a lousy epitaph.