Staff Sergeant Alfredo “Freddy” Rocha, U.S. Army (Retired) – 2 Iraqi Freedom Combat Deployments in a 20-Year Career

Military life is full of transitions. It begins with the transition from civilian to servicemember. Every two or three years thereafter, servicemembers and their families are uprooted from their homes, their jobs, and their schools to take new assignments, often far away in other countries. Sometimes military members must leave their peacetime assignments to deploy in times of war. Staff Sergeant Alfredo “Freddy” Rocha, U.S. Army (Retired), knows these transitions all too well. Two Iraqi Freedom combat deployments and two unaccompanied tours in South Korea tested Freddy’s ability to deal with transitions. With the help of others at every fork in the road, he navigated the course changes successfully.

Freddy was born in Orange County, California, in March 1977. He was a third-generation American, with his great-grandparents having emigrated from Mexico years before. Freddy’s father could not read or write, but he could work hard and work hard he did as a construction worker in the booming southern California economy. His mother worked hard, too, helping with programs distributing food stamps. Their motivation was clear—get the family out of poverty and into the middle class.

When Freddy was three, his parents moved their family to Norco, a city in Riverside County just west of Los Angeles. His home was typical of Mexican American households in the neighborhood at the time in that it was filled with cousins, other family members, and neighbors needing a place to stay. Freddy grew to love them all as family.

Unfortunately, gang activity was rampant in Freddy’s community, and his family was not immune. Some of his cousins were deep into gangs and many did serious time in prison. Freddy never joined a gang but always found himself on the fringe heading down the wrong path. This played out in his schooling when he was expelled from Norco High School during his freshman year. He had no intention of completing school anyway because one of his older brothers had dropped out and he saw how his father was able to earn a living by working hard. He knew, though, that he had to at least go through the motions until he was old enough to drop out for good.

Unable to return to Norco High, Freddy started attending the Corona-Norco Career Academy—an experimental high school designed to give kids who had gotten into trouble a second chance at their education. There Freddy excelled because he had the freedom to work more independently than in the structured environment of Norco High School. He still skipped school frequently and ran with the wrong crowd, but because he excelled at his schoolwork, no one tried to rein him in.

Freddy Rocha (right) with his lifelong friend, Johnny Canales (left)

Freddy Rocha (right) with his lifelong friend, Johnny Canales (left)Although Freddy never joined a gang, he and his best friend continued to get into trouble. Then Freddy started talking to a Vietnam veteran in his neighborhood, Steve Blunt. Blunt served in the special forces in Vietnam and was the first person to talk to Freddy like an adult. He leveled with Freddy and told him, “You’re f’ing up fast and picking up speed.” But what really impacted Freddy was when Blunt told him that if he continued down his current path, his actions would devastate his mother. Blunt then suggested Freddy consider the Army as a way to straighten out his life.

Blunt’s message resonated with Freddy. Motivated to change his life, he convinced a buddy to visit a recruiter with him in the fall of 1994. However, because Freddy was still seventeen, he needed both his parents to give their written permission to allow him to enlist. He told them he wanted to make a new life for himself, and the Army offered him the chance to do it. He also wanted to marry his high school sweetheart and that meant having a steady job that could transition into a career. By the time he finished speaking, he had convinced his parents, and they gave him their permission to enlist. Their only condition was he graduate from high school first.

Freddy did just that in the spring of 1995, graduating at the top of his class. He spent the summer enjoying a few more months of civilian life in southern California, painting houses and working at fast food restaurants to fund his fun. In the meantime, the buddy he had gone to the recruiter with was discharged from the Army for medical reasons. He told Freddy to get out of his commitment, saying Freddy would hate the Army because he didn’t like being told what to do. Freddy ignored his friend’s advice. He had given the Army his word he would enlist, and he intended to keep his promise.

True to his word, Freddy reported as directed to the Los Angeles Military Entrance Processing Station on August 23, 1994. There, he passed his final physical and took the oath of enlistment. Now officially in the Army, he boarded a plane the next day on his way to basic training at Fort Benning, Georgia.

Although Freddy’s plane landed in Atlanta late in the afternoon, the Army bus collecting new recruits for transport did not arrive at Fort Benning until 1:00 a.m. That’s when Freddy’s introduction to the Army and the South began. Everyone was directed to get off the bus and then escorted to the chow hall. There Freddy received a heaping helping of grits, which he had never tried before. He had eaten Cream of Wheat and Malt-O-Meal growing up, so he figured grits must be similar. Accordingly, he began to add butter and sugar to the grits. Out of nowhere, a recruit from West Virginia looked at him in disbelief and said with a strong southern accent, “What are you doing? You don’t put sugar on grits!” The experience made Freddy feel more Mexican than had ever felt in his life.

After a few hours of sleep, Freddy and the rest of the new recruits reported to the 30th Adjutant General Reception Battalion for in-processing. There they signed paperwork, received their uniforms, and got any shots they needed. They also learned their new training company assignments—Freddy’s was Delta Company of the 1st Battalion, 38th Infantry Regiment.

Freddy’s transition to Army life was rough. To begin with, he approached basic training with a chip on his shoulder. He hated being told what to do and initially did not get along with the other recruits. He saw them more as rivals rather than fellow trainees. Whenever there was a fight or even the hint of a fight among the recruits in his company, Freddy was involved. On the third night, he finally got “whooped” in a fight. The experience made him more tolerant of his peers.

The drill instructors were another matter—they scared Freddy. They were “big dudes” who got right in his face and screamed at him. On the streets back home, he never would have let anyone do that to him. Now it happened routinely. However, after Freddy started to make friends, things changed. He began to enjoy the training, even when he had to do extra pushups for laughing at other recruits when they did something wrong. Just as with high school at the Corona-Norco Career Academy, he excelled.

Freddy graduated from basic training on December 8, 1995. Next, he was scheduled to go to Airborne Jump School, where he would learn how to parachute out of airplanes. When he had enlisted, he’d committed to the airborne infantry, but he really didn’t know what it was at the time. Now that he did, he had a problem with it because he was afraid of heights. As all the new soldiers lined up for their respective follow-on training, Freddy stood with the infantry soldiers rather than with those heading to Jump School.

When a sergeant told Freddy to get in the Jump School line, Freddy told him he was afraid of heights. The sergeant didn’t want to hear it. So, after heading home on leave to Southern California to marry his high school sweetheart, Freddy returned to Fort Benning and began Jump School. Although at times his legs shook with intense fear, he successfully completed all his parachute jumps and graduated from the school. With Jump Wings now adorning his uniform, he received orders to report to the 82nd Airborne Division at Fort Bragg, North Carolina. From then on, it was “Airborne all the way.”

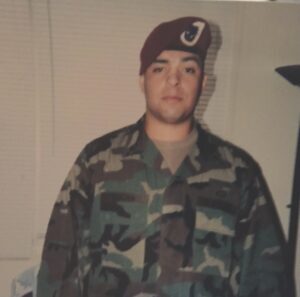

Private Freddy Rocha when assigned to the 82nd Airborne Division

Private Freddy Rocha when assigned to the 82nd Airborne DivisionFreddy arrived at Fort Bragg in February 1996. Because he was a new soldier fresh out of Jump School, the veterans subjected him and the other newly arriving soldiers to hazing. Freddy endured it all and became an integral member of the 82nd Airborne team. In April 1997, he deployed with his unit to Dharan, Saudi Arabia, where Khobar Towers had been bombed the year before. Freddy’s job was to provide security for a Patriot surface-to-air missile battery defending King Abdul Aziz Air Base. The deployment gave Freddy his first taste of an operational assignment outside the training environment, and he loved it. Even mundane tasks like donning his Mission Oriented Protective Posture (MOPP) gear, which is designed to protect soldiers from chemical and biological weapons, seemed exciting. He returned to Fort Bragg in August 1996 a motivated soldier.

Freddy made one additional deployment with the 82nd Airborne Division. This time it was to Belgium for training in early 2000. When he returned in March, he received orders to report to the 1st Battalion, 503rd Infantry Regiment, located at Camp Hovey in South Korea. Because the unit operated near the demilitarized zone (DMZ) between South and North Korea, Freddy could not take his family with him. This left his wife at home in charge of their two young children and their two older adopted children (a niece and a nephew). Knowing he would not see them again for a year, he said goodbye and boarded a plane for South Korea.

Although Freddy’s battalion was just fifteen miles from the heavily fortified DMZ and had to be always ready for a surprise attack from North Korea, his assignment proved uneventful until the day he was scheduled to depart. After celebrating the end of his tour with some buddies at bars in Seoul, he woke up in the barracks to his cell phone ringing. The call was from his wife asking him if he was going to war. Not knowing what had happened, he turned on the television and saw the second World Trade Center Tower being hit during the 9/11 terrorist attack on the United States.

Once word of the attack reached U.S. forces in South Korea, things moved quickly. Freddy’s unit, which had been exercising in the field without him, returned and Freddy was directed to immediately report to his defensive position with his weapon ready to repel any would-be attack. Unfortunately, he had already shipped all his belongings back to the States, including his uniforms and gear, because he had detached from his unit and was literally waiting to catch his flight home. Given the urgency of the moment, he hiked up the mountain to his defensive position carrying his weapon and live ammunition and wearing a t-shirt, flip-flops, cargo shorts, and a borrowed helmet. When his first sergeant saw him, he told him to get off the mountain, find a uniform, and get back into position ASAP. This Freddy did, and he found himself manning the position for eight days until things calmed down enough for him to return to the United States and rejoin his family.

Once back at Fort Bragg, Freddy received new orders to join Bravo Company of the 2nd Battalion, 3rd Infantry Regiment, at Fort Lewis, Washington. He reported on October 11, 2001—exactly one month after 9/11—and promoted to sergeant as soon as he arrived. His unit was part of the 3rd Stryker Brigade Combat Team. The Stryker was a new eight-wheeled armored vehicle with a crew of two and a troop compartment capable of carrying up to nine infantry soldiers. Freddy’s team was responsible for developing the tactics and standard operating procedures for deploying the Stryker with U.S. infantry units. That meant conducting training exercises to learn how to employ the vehicles with maximum effectiveness.

Freddy Rocha (right) in Iraq with one of his best friends, Jerry “Gonzo” Trejo (left)

Freddy Rocha (right) in Iraq with one of his best friends, Jerry “Gonzo” Trejo (left)Freddy’s situation changed when the Iraq War started in 2003. In November, he deployed in support of Operation Iraqi Freedom to Kuwait with Bravo Company as part of the 3rd Stryker Brigade Combat Team. He crossed with his company into Iraq in December to join the U.S. forces already in the country. The unit operated in northern Iraq, including in and around Mosul, employing the Stryker vehicle in combat operations for the first time. Freddy and the other members of his unit were tight and watched out for one another. In fact, his best friend, Gonzo, carried a photo of Freddy’s three-year-old daughter in his helmet because Freddy’s children were like family to him. Fortunately, Freddy’s company made it through the deployment without sustaining any casualties.

Freddy’s family was not as lucky. When he returned to Fort Lewis in August 2004, he and his wife separated and were divorced. Worse yet from Freddy’s perspective, his ex-wife was awarded custody of their kids. She did agree, though, not to move with the kids back to Southern California as long as Freddy was assigned at Fort Lewis. Seizing the opportunity, Freddy volunteered to stay with the 2nd Battalion, 3rd Infantry Regiment, for a second tour.

In June 2006, Freddy again found himself in Iraq as part of the 3rd Stryker Brigade Combat Team and Operation Iraqi Freedom. This time he was assigned to the battalion headquarters’ mobile operations center and was responsible for defending the center in the event of an attack. This happened on January 27, 2007, after an Apache attack helicopter was shot down in the vicinity of Najaf.

When Freddy’s Stryker arrived on scene and lowered its ramp so Freddy and the other soldiers onboard could disembark, they found themselves in the thick of a firefight with Hellfire missiles screaming into action nearby. Freddy’s unit quickly joined Charlie Company of the 2nd Battalion, 3rd Infantry Regiment, which was already in the fight, together with U.S. special operations forces and Iraqi Army soldiers, against hundreds of dug in Iraqi insurgents.

At one point after Freddy’s team set up the mobile operations center, Freddy heard the battalion commander radio the Charlie Company commander and ask for a situation report. The Charlie Company commander did not come to his radio. Instead, he could be heard shouting to his radio operator, “You tell him I’m in a firefight. I’ll update him when I can.” The fighting became so intense, Freddy promised God if he got out of it alive, he would quit smoking and marry his girlfriend. Enemy rockets flew everywhere while the special operations forces hammered away at the insurgents using a .50-caliber machine gun they salvaged from the downed helicopter. U.S. and British airpower joined the fight, and an AC-130 gunship devastated the insurgents with a barrage of fire from its rapid-firing cannons.

As the battle went on, Freddy’s sergeant major asked for help treating the wounded. Freddy volunteered because he had taken an emergency medical technician (EMT) course before the deployment. He grabbed a first aid kit and started to help, but he wasn’t prepared for the injuries he saw even though he’d seen casualties before and had not been affected by them. He collected himself by remembering he had a reputation to protect for being a tough soldier. Once he felt back in control, he returned to rendering aid.

The thirty-six-hour battle of Najaf was the fiercest action Freddy faced in Iraq, but other tough situations lay ahead. He lost a total of nineteen comrades during his brigade’s fifteen-month deployment, including some killed when improvised explosive devices destroyed the vehicles they rode in. Even Freddy was injured in a vehicle rollover accident.

Staff Sergeant Freddy Rocha with his daughter, Aleina, and his son, Fredo, when he returned from his second Iraq deployment

Staff Sergeant Freddy Rocha with his daughter, Aleina, and his son, Fredo, when he returned from his second Iraq deploymentWhen the 3rd Stryker Brigade Combat Team finally returned to Fort Lewis in September 2007, it received a hero’s welcome. Freddy’s girlfriend, his parents, and his children were all on hand to welcome him home and watch Freddy’s unit march by. It was the first time Freddy’s father had seen him in uniform, and it made Freddy feel proud.

Still, Freddy was tired. He’d been in the Army for twelve years and spent much of that time deployed, including twice to Iraq. So, when it came time to reenlist, Freddy asked for orders to a command at Fort Lewis that would not deploy. He also requested the colonel of the 2nd Battalion, 3rd Infantry Regiment, administer his reenlistment oath. Both the colonel and Freddy found that funny because the colonel had “busted” Freddy in rank twice at Article 15 nonjudicial punishment proceedings while they were deployed in Iraq. But the colonel knew Freddy was a good soldier and believed in him, so he was happy to help Freddy reenlist. He also congratulated Freddy for surviving Iraq and for continuing with his Army career.

For the next three years, Freddy was assigned at Fort Lewis to Charlie Company of the 1st Battalion, 357th Infantry, training National Guard units to deploy. On the job, he specialized in teaching short-range marksmanship. Off the job, he rehabilitated injuries he’d received overseas, got married, and earn his bachelor’s degree.

In March 2011, Freddy received orders to return to South Korea, this time as a platoon sergeant for one of two infantry companies assigned to the 1st Battalion, 72nd Armored Regiment, at Camp Humphreys. The concept was for the infantry companies, operating with their Bradley Fighting Vehicles, to learn to fight side-by-side with the tanks of the 72nd Armored Regiment. Freddy found the experience professionally rewarding and challenging. He motivated the soldiers in his platoon by reminding them they were training on ground fought for and won by the blood of U.S. soldiers during the Korea War just sixty years before.

Freddy returned to Fort Lewis in March 2012. At the request of his former battalion commander, he again took a job with the 1st Battalion, 357th Infantry, thinking it might be his last tour. He’d been tired ever since the battle of Najaf and was still having trouble dealing with his experience in Iraq. He tried to present an image of being a tough staff sergeant. After all, he’d been in combat and had earned the Expert Infantryman badge. But now, for his own well-being, he knew he had to change direction and find a job that involved helping people. His initial thoughts were to become a nurse. He just needed a sign before deciding to part company with the Army and retire. That sign came when he did not make sergeant first class.

Freddy officially retired on September 1, 2015, after serving twenty years and seven days on active duty. He then followed through on his goal of becoming a nurse by going to school to become a Certified Nursing Assistant. As part of his studies, he took a job at a nursing home to gain some practical experience. That experience taught him a nursing career would not be a good fit for him.

The transition to civilian life continued to prove difficult. All his life, he’d been an infantryman, and now that he was retired, suddenly everything he knew and valued was gone. A friend of his set up a meeting for him with a woman at the local Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW) post and the woman asked him to bring his medical record. After the meeting, she helped him file a disability claim, which at the time he really didn’t understand. In fact, he felt like he was spiraling out of control. He visited the gravesite of one of his best friends killed in Iraq. He’d not attended any ceremonies honoring his fallen comrades in the past, suppressing any emotions he had by focusing on the mission at hand. Now it all came crashing down and he questioned how he could go on. He thought no one cared.

The turning point came one day when his car overheated. By chance, he pulled into the parking lot of VFW Post 2224 in Puyallup, Washington, and went inside to ask if he could use a hose to add water to his radiator. Carlos Alameda offered to help, and they began to talk. Immediately, Freddy knew Carlos understood him and what he was going through. Carlos invited Freddy to learn more about the VFW’s programs and showed him ways he could start helping other people through the VFW. It was just the medicine Freddy needed. Soon, the friendships he made at the Post started to fill the void he felt after leaving the Army. He felt like he had a purpose again.

Even after Freddy found the VFW, his life wasn’t all smooth sailing. It was, however, on the right trajectory. Although he divorced again in 2017, he remained on good terms with his ex-wife. Then, after his youngest daughter graduated from high school in June 2018, he moved to Springfield, Illinois. There he earned his master’s degree and accepted a position with the University of Illinois Springfield as an admissions counselor. He later transitioned to the Illinois Department of Veterans Affairs as a full-time veteran service officer. Essentially everything Freddy now does centers around helping veterans and their families, and that is just the way he wants it.

Voices to Veterans is proud to salute Staff Sergeant Alfredo “Freddy” Rocha, U.S. Army (Retired), for his twenty years of distinguished service to our country. Freddy willingly went wherever the Army needed him most, including two unaccompanied tours to South Korea and two combat deployments to Iraq. After successfully accomplishing all the Army asked of him, he returned to civilian life where he now devotes his time and energy to helping veterans and their families succeed. We thank him for all he has done and wish him fair winds and following seas.

If you enjoyed Freddy’s story, please sign up for the Voices to Veterans Spotlight monthly newsletter by clicking here. Once each month, you’ll receive a new written veteran’s story directly in your mailbox. Best of all, it’s free and you can unsubscribe at any time.

Staff Sergeant Freddy Rocha (second from right on first row) with other soldiers from the 1st Battalion, 357th Infantry

Staff Sergeant Freddy Rocha (second from right on first row) with other soldiers from the 1st Battalion, 357th Infantry The post Staff Sergeant Alfredo “Freddy” Rocha, U.S. Army (Retired) – 2 Iraqi Freedom Combat Deployments in a 20-Year Career first appeared on David E. Grogan.