Desert Island Desks

The Lonely Island

The Lonely IslandK-12 classroom teaching is a weird job. It may be one of the weirdest jobs that adult people can have. In some ways, it’s radically unlike anything else adults do.

For one thing, obviously, it’s done exclusively for children. That’s not a common thing among grown-up jobs, but it’s not that unusual. There are many doctors and nurses whose practices focus on children, for example.

What’s unusual about teaching is that it’s done surrounded by children—in near or total isolation from other adults and peers. Sure, some teachers may have a paraprofessional in the room, or a co-teacher, or a student teacher—but many do not. For many teachers, perhaps even most teachers, they are alone with children all day. Their professional practice is done in isolation, with only children as witnesses. When they see other adults, it is by and large not when they are engaged in teaching. They see their peers at lunch, they see their peers in staff meetings, they see their peers at after-school events, but what they don’t do very often is see their peers doing their jobs.

That’s highly strange. Try to think of another place where people never see their co-workers doing their jobs—never work next to others, never collaborate on things, never measure themselves against other people, never envy other people’s moves, never steal their tricks, never learn by watching. Try to think of another job where no one ever watches you do the job or sees the output of the work you’re doing. It’s weird.

Yes, some administrators demand that teachers turn in lesson plans on a regular basis. They may even review them (I’m dubious, but let’s go with it). That’s some level of oversight, but it’s indirect. The lesson plan is not the lesson, any more than the script is the play. You need to watch the performance to get the whole picture.

And yes, administrators do observe their teachers on some formal cadence in order to evaluate them. But those classroom observations are shockingly rare, limited in scope, and hemmed in by union contracts. And they’re usually planned in advance.

Are they truly representative of what goes on in the classroom every day? I mean…maybe? Let’s say yes, for argument’s sake (though, again, I’m dubious). Even so, how many people do you know whose managers observe their work just once a year, for 10 or 15 minutes? How many employees get to tell their managers when they’re allowed to observe their work, and in what way, and for how long?

What I’m saying is that K-12 teaching is basically invisible to other adults within the profession and adjacent to it, in a way that no other job I can think of is. It’s weird. And it has some weird effects.

First of all, how do you know if you’re good at the job if no one ever sees you doing it? Trial lawyers may work solo, but they work in public. Their work is visible. Judges see them. Juries see them. Other lawyers see them. If you’re in that business, there are many ways to know if you’re any good. Long-haul truck drivers work alone, but they have pretty clear and quantifiable goals. Did they get their truck where it was meant to be, in the time allotted, with the cargo safely delivered? Good job. Did they do it without causing any accidents or getting any tickets? Great job.

What are your success metrics if you’re a teacher? The kids get good grades on tests? They pass their classes? Sure. Those are real and important things. But if you’re the teacher, you’re the one who decides whether they pass that test or that class. Grading your own performance on a rubric of your own invention is…well, it’s a little suspect, isn’t it? Would you be allowed to do that at your job?

Look, maybe their rubrics are entirely fair and objective. But there are a ton of variables in the mix alongside the teacher’s performance, and they’re hard to separate out and evaluate (which is, to be fair, why teachers are so uncomfortable with the idea of performance-based evaluation in the first place). Maybe the kids are just smart and capable this year. Maybe the textbook does a great job on its own. Maybe their teacher last year did a great job preparing them. How can a teacher be sure about what they personally have added to the recipe?

When John Hattie engaged in his famous meta-study of meta-studies that became the 2008 book, Visible Learning, he realized that it was crazy to try to evaluate the statistical effect of any particular teaching practice by starting at zero. Kids learned and grew whether they went to school or not. Kids learned just by growing up in the world. Kids learned by being in the presence of knowledgeable adults who talked to them. To measure a particular practice or strategy or resource, he had to create some kind of “hinge point” above zero to show the added benefit, if there was any.

As you can see below, the hinge point for evaluating a particular strategy or technique is set above any developmental effects and generic “teacher effects.” Hattie takes those things as given, and he starts his measurement above them, at 0.4. Anything that scores above 0.4 is a strategy or technique that additively boosts student performance.

Do teachers know this research? Do they know which strategies and resources have been shown to make a difference? And do they know what’s happening in that wedge called “teacher effects?” Do they know if what they’re doing is additive, or subtractive, or entirely meaningless? And—if they are using Proven Technique X, do they know if they’re doing X correctly, or better than the teacher down the hall?

In my teaching career, such as it was, these were not questions asked by anybody, or even whispered quietly to ourselves. It never occurred to us. We assumed we were good teachers because…well, because we thought we were. Because our kids seemed happy and engaged. Or healthy and present. Or maybe just quiet and obedient. It kind of depended on what the individual teacher valued. And that’s the problem. Our individual values were the only metric that mattered, because, as teachers are fond of saying, when they close that classroom door, the principal and the school board and the state department of education aren’t there. The teacher does what they think is best.

How can you tell whether every teacher in an academic department, or every teacher in a school, thinks that the same thing is best?

You can’t.

How can you tell whether every teacher who thinks X is the right thing to do is doing X correctly and effectively?

You can’t.

You can’t, because the only people who are in a position to evaluate them routinely, ongoingly, the only people who can compare their practice to someone else’s, are the people who move from one teacher to the next throughout the day, or from one year to another. Those are the schoolchildren. And nobody listens to them.

Inside the Dunning-Kruger MachineAs I said, none of this occurred to me when I was a classroom teacher. I didn’t notice any of it until I started traveling to classrooms to observe teachers implementing curriculum materials I had created. That was the first time in my life that I had gone from classroom to classroom, seeing the variety of practice and competence in the profession.

The idea that I was seeing something that most teachers couldn’t see was reinforced when I started doing my doctoral research. I wanted to study how well high school teachers understood and used principles of differentiated instruction in their classrooms. My suspicion, going in, was that most teachers understood the concepts well enough, but that they found them logistically impossible to implement in the restricted class periods of traditional high schools and the frenzied pace of “coverage” they were held accountable to. That was my thesis: they get it; they just find it impractical.

Boy, was I wrong.

What I discovered was that every teacher I interviewed was convinced that they knew what differentiated instruction was and that they were implementing it correctly. They were mistaken on both counts. Many of them confused differentiated instruction with multiple intelligences. Some of them confused differentiated instruction with old-fashioned, academic tracking. But each of them was absolutely convinced that they were correct, because there was no one in their room watching them who could correct them, and no one whose room they visited, who might have been doing it differently.

Almost every teacher I spoke with believed fiercely not only in their professional knowledge and competence, but also in their administrators’ inability to understand and evaluate their performance. Only they, the teachers, were in a position to be able to judge what they were doing.

Who dares judge me?

There were exceptions. A handful. A few teachers were more thoughtful, more self-critical, and more open to learning and growing in their profession. And this small group all shared one trait: they had all been in training programs or schools where peer observation was supported and expected as part of the professional culture. They saw other teachers at work—all the time—and it made them think more critically about their own work and the level of their own practice. They tried out new things—not randomly, but because they saw those things work in other rooms. They improved their practice. And in this way, they were radically different from everyone else I spoke with.

Building a Better TeacherI am not the first to have discovered this. Not by a long shot. Teachers in Japan have been engaging in a collaborative form of instructional review called lesson study for over 150 years. It has gotten some traction in some places here in the States, but it is not widespread. It flowers in some places, and then it tends to wither. It does not take root and spread.

In the video below and in her excellent, 2014 book, Building a Better Teacher, Elizabeth Green explains some of the challenges with lesson study and with teacher training in general.

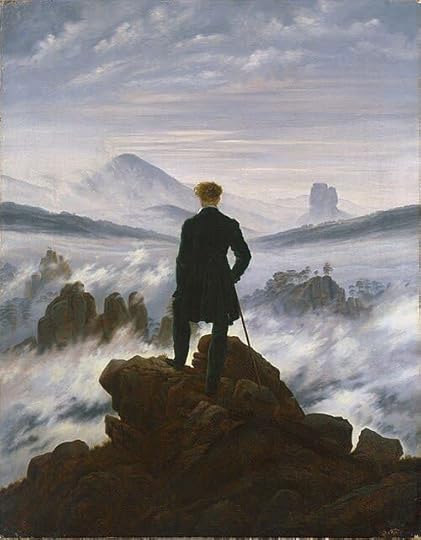

Forward?The books I’ve referenced in this post are at least ten years old. Much of what was “uncovered” by Hattie or by Green was already known by plenty of people—intuitively if not quantifiably. Carol Ann Tomlinson started writing about differentiated instruction in the mid-1990s, and she was systematizing existing practice more than she was inventing anything new. We’ve been teaching our children, formally or informally. for as long as we’ve been having children. We’ve been talking and writing about how to teach them since at least Plato and Aristotle’s time. But the way we approach teacher training in this country, and the weird isolation in which we make teachers work, is crazy.

We know what we can do to make teaching better. It’s not a fog-shrouded mystery. We know. We just…don’t do it. It’s difficult. It requires changing our assumptions, and our practices, and our recruiting practices, and our training systems, and maybe even our school schedules. It’s exhausting just to list all those things. Who needs the hassle?

Change is hard. We’re immovable objects, and we need a really compelling, irresistible force to get us off our asses. Right now, the incentives to change are theoretical at best, while the incentives to put your head down and wait for the change initiative to blow away are pretty strong and time-tested. Administrators have proved to teachers, time after time and in place after place, that if teachers simply wait them out, the change agents will give up and move on. And if the students don’t protest, and the parents don’t complain, why should they change what they’ve been doing? Isn’t the job hard enough already?

So, don’t complain that the system is broken. Every system is a perfect machine for delivering the results it actually delivers. The system isn’t broken just because we don’t like what we’re getting out of it. The system is doing what it was designed to do.

If we don’t like what it’s doing or what we’re getting, we know what to do.

Scenes from a Broken Hand

- Andrew Ordover's profile

- 44 followers