Andrew Ordover's Blog: Scenes from a Broken Hand

November 28, 2025

Desert Island Desks

The Lonely Island

The Lonely IslandK-12 classroom teaching is a weird job. It may be one of the weirdest jobs that adult people can have. In some ways, it’s radically unlike anything else adults do.

For one thing, obviously, it’s done exclusively for children. That’s not a common thing among grown-up jobs, but it’s not that unusual. There are many doctors and nurses whose practices focus on children, for example.

What’s unusual about teaching is that it’s done surrounded by children—in near or total isolation from other adults and peers. Sure, some teachers may have a paraprofessional in the room, or a co-teacher, or a student teacher—but many do not. For many teachers, perhaps even most teachers, they are alone with children all day. Their professional practice is done in isolation, with only children as witnesses. When they see other adults, it is by and large not when they are engaged in teaching. They see their peers at lunch, they see their peers in staff meetings, they see their peers at after-school events, but what they don’t do very often is see their peers doing their jobs.

That’s highly strange. Try to think of another place where people never see their co-workers doing their jobs—never work next to others, never collaborate on things, never measure themselves against other people, never envy other people’s moves, never steal their tricks, never learn by watching. Try to think of another job where no one ever watches you do the job or sees the output of the work you’re doing. It’s weird.

Yes, some administrators demand that teachers turn in lesson plans on a regular basis. They may even review them (I’m dubious, but let’s go with it). That’s some level of oversight, but it’s indirect. The lesson plan is not the lesson, any more than the script is the play. You need to watch the performance to get the whole picture.

And yes, administrators do observe their teachers on some formal cadence in order to evaluate them. But those classroom observations are shockingly rare, limited in scope, and hemmed in by union contracts. And they’re usually planned in advance.

Are they truly representative of what goes on in the classroom every day? I mean…maybe? Let’s say yes, for argument’s sake (though, again, I’m dubious). Even so, how many people do you know whose managers observe their work just once a year, for 10 or 15 minutes? How many employees get to tell their managers when they’re allowed to observe their work, and in what way, and for how long?

What I’m saying is that K-12 teaching is basically invisible to other adults within the profession and adjacent to it, in a way that no other job I can think of is. It’s weird. And it has some weird effects.

First of all, how do you know if you’re good at the job if no one ever sees you doing it? Trial lawyers may work solo, but they work in public. Their work is visible. Judges see them. Juries see them. Other lawyers see them. If you’re in that business, there are many ways to know if you’re any good. Long-haul truck drivers work alone, but they have pretty clear and quantifiable goals. Did they get their truck where it was meant to be, in the time allotted, with the cargo safely delivered? Good job. Did they do it without causing any accidents or getting any tickets? Great job.

What are your success metrics if you’re a teacher? The kids get good grades on tests? They pass their classes? Sure. Those are real and important things. But if you’re the teacher, you’re the one who decides whether they pass that test or that class. Grading your own performance on a rubric of your own invention is…well, it’s a little suspect, isn’t it? Would you be allowed to do that at your job?

Look, maybe their rubrics are entirely fair and objective. But there are a ton of variables in the mix alongside the teacher’s performance, and they’re hard to separate out and evaluate (which is, to be fair, why teachers are so uncomfortable with the idea of performance-based evaluation in the first place). Maybe the kids are just smart and capable this year. Maybe the textbook does a great job on its own. Maybe their teacher last year did a great job preparing them. How can a teacher be sure about what they personally have added to the recipe?

When John Hattie engaged in his famous meta-study of meta-studies that became the 2008 book, Visible Learning, he realized that it was crazy to try to evaluate the statistical effect of any particular teaching practice by starting at zero. Kids learned and grew whether they went to school or not. Kids learned just by growing up in the world. Kids learned by being in the presence of knowledgeable adults who talked to them. To measure a particular practice or strategy or resource, he had to create some kind of “hinge point” above zero to show the added benefit, if there was any.

As you can see below, the hinge point for evaluating a particular strategy or technique is set above any developmental effects and generic “teacher effects.” Hattie takes those things as given, and he starts his measurement above them, at 0.4. Anything that scores above 0.4 is a strategy or technique that additively boosts student performance.

Do teachers know this research? Do they know which strategies and resources have been shown to make a difference? And do they know what’s happening in that wedge called “teacher effects?” Do they know if what they’re doing is additive, or subtractive, or entirely meaningless? And—if they are using Proven Technique X, do they know if they’re doing X correctly, or better than the teacher down the hall?

In my teaching career, such as it was, these were not questions asked by anybody, or even whispered quietly to ourselves. It never occurred to us. We assumed we were good teachers because…well, because we thought we were. Because our kids seemed happy and engaged. Or healthy and present. Or maybe just quiet and obedient. It kind of depended on what the individual teacher valued. And that’s the problem. Our individual values were the only metric that mattered, because, as teachers are fond of saying, when they close that classroom door, the principal and the school board and the state department of education aren’t there. The teacher does what they think is best.

How can you tell whether every teacher in an academic department, or every teacher in a school, thinks that the same thing is best?

You can’t.

How can you tell whether every teacher who thinks X is the right thing to do is doing X correctly and effectively?

You can’t.

You can’t, because the only people who are in a position to evaluate them routinely, ongoingly, the only people who can compare their practice to someone else’s, are the people who move from one teacher to the next throughout the day, or from one year to another. Those are the schoolchildren. And nobody listens to them.

Inside the Dunning-Kruger MachineAs I said, none of this occurred to me when I was a classroom teacher. I didn’t notice any of it until I started traveling to classrooms to observe teachers implementing curriculum materials I had created. That was the first time in my life that I had gone from classroom to classroom, seeing the variety of practice and competence in the profession.

The idea that I was seeing something that most teachers couldn’t see was reinforced when I started doing my doctoral research. I wanted to study how well high school teachers understood and used principles of differentiated instruction in their classrooms. My suspicion, going in, was that most teachers understood the concepts well enough, but that they found them logistically impossible to implement in the restricted class periods of traditional high schools and the frenzied pace of “coverage” they were held accountable to. That was my thesis: they get it; they just find it impractical.

Boy, was I wrong.

What I discovered was that every teacher I interviewed was convinced that they knew what differentiated instruction was and that they were implementing it correctly. They were mistaken on both counts. Many of them confused differentiated instruction with multiple intelligences. Some of them confused differentiated instruction with old-fashioned, academic tracking. But each of them was absolutely convinced that they were correct, because there was no one in their room watching them who could correct them, and no one whose room they visited, who might have been doing it differently.

Almost every teacher I spoke with believed fiercely not only in their professional knowledge and competence, but also in their administrators’ inability to understand and evaluate their performance. Only they, the teachers, were in a position to be able to judge what they were doing.

Who dares judge me?

There were exceptions. A handful. A few teachers were more thoughtful, more self-critical, and more open to learning and growing in their profession. And this small group all shared one trait: they had all been in training programs or schools where peer observation was supported and expected as part of the professional culture. They saw other teachers at work—all the time—and it made them think more critically about their own work and the level of their own practice. They tried out new things—not randomly, but because they saw those things work in other rooms. They improved their practice. And in this way, they were radically different from everyone else I spoke with.

Building a Better TeacherI am not the first to have discovered this. Not by a long shot. Teachers in Japan have been engaging in a collaborative form of instructional review called lesson study for over 150 years. It has gotten some traction in some places here in the States, but it is not widespread. It flowers in some places, and then it tends to wither. It does not take root and spread.

In the video below and in her excellent, 2014 book, Building a Better Teacher, Elizabeth Green explains some of the challenges with lesson study and with teacher training in general.

Forward?The books I’ve referenced in this post are at least ten years old. Much of what was “uncovered” by Hattie or by Green was already known by plenty of people—intuitively if not quantifiably. Carol Ann Tomlinson started writing about differentiated instruction in the mid-1990s, and she was systematizing existing practice more than she was inventing anything new. We’ve been teaching our children, formally or informally. for as long as we’ve been having children. We’ve been talking and writing about how to teach them since at least Plato and Aristotle’s time. But the way we approach teacher training in this country, and the weird isolation in which we make teachers work, is crazy.

We know what we can do to make teaching better. It’s not a fog-shrouded mystery. We know. We just…don’t do it. It’s difficult. It requires changing our assumptions, and our practices, and our recruiting practices, and our training systems, and maybe even our school schedules. It’s exhausting just to list all those things. Who needs the hassle?

Change is hard. We’re immovable objects, and we need a really compelling, irresistible force to get us off our asses. Right now, the incentives to change are theoretical at best, while the incentives to put your head down and wait for the change initiative to blow away are pretty strong and time-tested. Administrators have proved to teachers, time after time and in place after place, that if teachers simply wait them out, the change agents will give up and move on. And if the students don’t protest, and the parents don’t complain, why should they change what they’ve been doing? Isn’t the job hard enough already?

So, don’t complain that the system is broken. Every system is a perfect machine for delivering the results it actually delivers. The system isn’t broken just because we don’t like what we’re getting out of it. The system is doing what it was designed to do.

If we don’t like what it’s doing or what we’re getting, we know what to do.

November 21, 2025

Inflatable America

We are the hollow men

We are the stuffed men

Leaning together

Headpiece filled with straw. Alas!

— T.S. Eliot

The Straw Man TrialOnce upon a time, when I worked for a university theater department, I wrote a couple of courtroom dramas based on actual trials, to be staged in the mock trial room of the law school where my father worked. The first play was based on Aaron Burr’s trial for treason in 1807. The second play was based on the 1987 congressional testimony around the Iran-Contra scandal. One play was ancient history to me; the other was about events that had taken place a year before I was writing.

Those Iran-Contra hearings went on forever, with many witnesses, but the star of the show had been Colonel Oliver North, who had shown up in full military regalia, ramrod straight—unrepentant and contemptuous of the whole proceeding. The news media, objective as always, loved taking pictures of him from below to make him look large and imposing. Heroic. He wasn’t some crazed zealot who was caught breaking the law. No, no—he was a patriot doing his duty for his country. Obviously, any play I wrote would have to be about him.

However. Because I had so recently been immersed in early American history and was fascinated with the figure of Aaron Burr (long before he became a cultural icon), I came up with a strange and twisty idea. I would use Oliver North’s testimony, but I would put him on trial in a mythical court of the pantheon of American Heroes, to see if he qualified to be counted among their members. It would be a play about us, not him.

I had Young Thomas Jefferson, circa the writing of the Declaration of Independence, as the prosecuting attorney, there to protect the honor of the Mount Rushmore pantheon against this upstart. His argument was that we loved our leaders and heroes because they adhered to the highest ideals of the country’s founding. They certainly wouldn’t do something like selling arms to a hostile country in order to finance the clandestine work of rebels to whom Congress had already cut off funding.

And Aaron Burr, in disgrace after the Hamilton shooting and his treason trial, was there to defend Oliver North and claim for him his rightful place in the pantheon. He was sly, cynical, with a wry sense of humor about himself, his opponent, and the whole concept of “highest ideals.”

As Jefferson called on mythic figures like George Washington, Abraham Lincoln, and Theodore Roosevelt, each witness testified about their love of American values and ideals, speaking only in words they had actually spoken or written in life. During cross-examination under Burr, they continued to say only the things they had said in life—but this time, Burr pushed them to talk about the primacy of protecting and extending American strength and power, regardless of cost or moral queasiness. As in any good cross-examination, our heroes’ testimony to Burr often undermined or impeached what they had just said to Jefferson.

That was the first act.

In Act Two, Burr brought his case. First came Oliver North, represented by a literal straw man, with the court clerk reading the greatest hits from his congressional testimony. Most of the audience knew the basics of the story, and many of them had watched the testimony just a year before, so I didn’t have to dwell on it too much. We all knew what he had done and why he felt it was justified.

Then Burr called his only other witness: Thomas Jefferson. But it wasn’t young Jefferson, the man who sat across the courtroom from Burr. It was old Tom: ex-President Jefferson. Burr got him to talk about all the things he had done to increase and extend American Power, whether moral, idealistic, legal, or not. And then, in the climax of the play, young Jefferson got to cross-examine old Jefferson, with the ideals of youth crashing against the realpolitik of age and experience.

And then the jury had to vote.

It was a university audience—a mix of students, faculty and staff—predisposed to be liberal. But they didn’t always vote against North. There were nights when they grudgingly (and one night tearfully) accepted that, within the arguments that had been presented to them, what North did was no worse, and perhaps not that much different, from what any of the Great Men would have done or endorsed.

It was a nasty piece of manipulation on my part, but, on the other hand, real juries never get to vote on how they feel about something; they are always constrained by the evidence brought before them. And that evidence is never the whole story.

But it felt like a fair argument to grapple with. Did we really believe in the things we cheered for and voted for? Because I did—even after doing research for that play, which, believe me, was damned depressing. I was a firm believer in that thing Bill Clinton used to say, that there was nothing wrong with America that couldn’t be fixed by what was right with America.

But was I fooling myself? Were we all lying to ourselves—hiding from what we actually, deep down, wanted from our leaders? Were the ideals just pretty words to hide the brute force that we really wanted from our leaders? America uber alles, ideals be damned?

It sure feels that way, these days—which is why, I guess, I’ve been thinking about that old play.

Blow Up DollsWhat is it about the play that’s been nagging at me? I think it has something to do with those immigrants we’ve been terrorizing and dragging off American streets and those fishermen we’ve been blowing up in the Caribbean and those reporters and congressmen and university presidents our government has been threatening and strongarming into obedience. The political discourse seems to have boiled itself down to nothing but STRENGTH versus WEAKNESS, with the former being so essential as to be worth paying any price and the latter being a horrifying thing that must be avoided at any cost. We cannot afford to think about lofty ideas. We must bring down the hammer. Everywhere. We must be strong.

But what do we even mean by that?

Start at the bottom and work your way up. We hear a lot these days about “toxic masculinity,” but what I actually see around me is more like “blow-up doll masculinity.” Serious, sober adulthood and protecting the vulnerable don’t seem to be the ideal anymore; being swole is—oversized in body, oversized in ego, oversized in aggression. Real men aren’t careful or cautious or prudent or protective; they are simply big. Big-dick energy. Leading with the chest, looking for a fight. Come at me, bro.

Fitness isn’t about health anymore; it’s about muscles erupting out of your clothes. Not comfort, but swagger. Not what you need for yourself, but what you need to show off to others.

Wealth isn’t about security anymore; it’s about being able to buy baby yachts to keep your big yachts company. Not comfort, but swagger. Not what you need for yourself, but what you need to show off to others.

Is that strength at an individual level? “Strong” doesn’t seem to have anything to do with a sense of calm that comes from confident competence, or a sense of quiet resolve based on character. It’s not inner anything; it’s just an outward show of dominance and aggression.

Roll that up to the national level and look at what it’s done. National strength ought to mean something like stability, prosperity, and health—the ability of a people to lead happy, safe lives. Strong leaders do what is necessary to secure those things for their people.

So, what kind of strength do we need from our leaders these days?

We live in a place and a time blessed by abundant wealth, health, and resources, both intellectual and natural—maybe more so than in any other place or time in history. That’s true, even when the stock market is taking a dip or grocery prices seem to be rising. We may be feeling a little wobbly right now, but compared to other countries and certainly compared to past eras of history, we should be able to feel magnanimous and gracious to our neighbors and to the rest of the world.

But you wouldn’t think that to look at us today. Within our secure borders and warm homes, we’re animated by suspicion, selfishness, and fear.

And beyond those borders? Shouldn’t the idea of “projecting strength abroad” involve things like USAID, the Peace Corps, and support for democratic institutions and human rights? Isn’t that how a confident, secure, and strong country relates to its neighbors?

Well, that’s not us. We’ve slashed funding for aid programs at home and abroad. We’ve sent gunboats to threaten foreign leaders we don’t like, and our president uses social media to threaten citizens who oppose him. We’ve blown up fishing boats, claiming that we’re under invasion. We’ve sent masked, armed thugs into American cities to terrorize immigrants who have lived among us for years, convinced somehow that they are threatening our way of life.

I don’t know. It feels to me like that’s just not how strong people behave.

I guess it shouldn’t be surprising that we’re being ruled by braying, swaggering bullies. Men all over the country seem to be idealizing a cartoon-character version of masculinity, no more real than a giant balloon at the Macy’s Thanksgiving parade. Centuries of philosophy and ethical writing about leading a grounded, virtuous, and meaningful life—almost exclusively written by men, for men, and about men—and in our own time, manhood comes down to, “Do you even lift, bro?”

If that’s the case, it’s not surprising that we elected a man who projects masculinity in such ludicrously ersatz and inflated ways—the big hair, the shoulder pads, the giant ties, the shoe lifts, the baggy suits, the inflated ego, the boastful sex talk, and the refusal ever to apologize or admit error about anything?

I don’t even blame him. He is who he is. We’ve known him for a long time. He’s been in our faces for decades. If his voters were blindsided or fooled by him, that’s on them. But I don’t think many of them were. I think they liked what they saw. They held it up for admiration and emulation. They wanted it, and they wanted to be just like it. He claimed to be strong, and they wanted what they saw as strength.

We used to hold up movie characters like Atticus Finch for emulation. Now we seem to celebrate Biff Tannen. But Biff was the bad guy. I thought we all understood that.

This isn’t only a male problem. Not when you can search for “Mar-a-Lago Face” and “tradwives” online. We’re all becoming blow-up-doll versions of people, with every bit of nuance and complication Botox-ed out of existence, and the most extremely and stereotypically male and female traits inflated into comic proportions. And across the board, boasting, braying, and bullying are celebrated as qualities to admire.

Like balloons, we expand and puff ourselves out, but we’re full of nothing but air. And that air won’t lift us or let us fly. We’ll just pump ourselves up until we explode.

What is Strength?The men who founded our country and crafted a political structure that gave ordinary people power and agency to direct their lives—they spent a lot of their youth reading deeply in Greek and Roman history and philosophy. The way those men thought and lived was rooted in what they studied as young men (as Thomas Ricks details in this fascinating book).

They weren’t perfect, God knows—not as people and not as leaders. They often fell miserably short of their ideals. But at least they had some. They tried to live by words like, “When someone is properly grounded in life, they shouldn’t have to look outside themselves for approval” (Epictetus), and “The best revenge is to be unlike him who performed the injury” (Marcus Aurelius), and “Man conquers the world by conquering himself” (Zeno). They set a standard for the rest of us—one they fell short of; one we all fall short of. But a standard is a good thing to have, to measure yourself by.

What happened to the idea that self-control was the sign of strength, not vindictive lashing out at everyone and everything around you?

How did we come to equate strength with drunk-guy-at-the-bar aggressiveness and strutting, self-congratulatory boastfulness, when for so much of our history, we identified those behaviors as signs of weakness?

The Skin of Our TeethOne of my favorite plays, which is too big and weird to be done much, is Thornton Wilder’s The Skin of Our Teeth. It’s an epic play about a family’s survival though eons of disasters and catastrophes—ice ages, floods, and wars. They are the eternal human family—they are all of us.

In the final act, in the ruins of a terrible war, the teenaged son returns from the front, eager to keep fighting and tear down everything he found oppressive in the old world. His father reaches out to him and says, “Let’s try again.” And this is what happens:

HENRY:

Try what? Living here? Speaking polite to old men like you? Standing

like a sheep at the corner until the red light turns green? Being a good

boy and a good sheep, like all the stinking ideas you get out of your

books? Oh, no. I’ll make a world, and I’ll show you.

MR. ANTROBUS:

How can you make a world for people to live in, unless you’ve

put yourself in order first? Mark my words: I shall continue

fighting you until my last breath, as long as you mix up your idea

of liberty with your idea of hogging everything for yourself….

HENRY:

I don’t belong here. I have nothing to do here. I have no home.

MR. ANTROBUS:

When your mother comes in you must behave yourself. Do you hear me?

HENRY:

What is this? Must behave yourself? Don’t you say must to me. Nobody can say must to me. All my life everybody’s been crossing me—everybody, everything, all of you. I’m going to be free, even if I have to kill half the world for it.

“I’m going to be free, even if I have to kill half the world for it.”

Is that strength, or is Mr. Antrobus right, that you can’t make a world for people to live in unless you’ve “put yourself in order first?”

When you are calm in yourself—when you know yourself and can accept yourself with a quiet, humble confidence—you don’t end up reacting to other people from a position of fear or envy or suspicion. You don’t care about what they have, because you are satisfied with what you have—whatever you have. You don’t care how they live their lives, because you are content in the way you live yours. You don’t have to spend every moment worried about how immigrants or Jews or Muslims or gay people or trans people are undermining or weakening or challenging your world, because you are secure in your own world—and, therefore, you can let them have their piece and their peace without feeling threatened. You know that there is world enough and time for all of us. It’s not all being taken away from us. It’s not all about to end—not with a bang or with a whimper. The world is not pie; it’s sky—open and limitless and everyone’s.

As Joni Mitchell might have said, it’s strength’s illusions we recall. We really don’t know strength at all.

November 14, 2025

We Make the Path by Stumbling

I came to ambition late in life, although I had plenty of delusions as a child. I thought I was going to be a famous novelist, and then I thought I was going to be a famous playwright—unclear what it meant to be a working professional in either of those fields, much less a famous one.

I wonder sometimes, what did I think it meant to make a living, back when I was a child? How did I think the game was played? What did I think was required of me? What did I think I was supposed to do?

I didn’t have a clue. I don’t think I even had a clue that I didn’t have a clue.

What Was College For?I grew up in a high-pressured, college-prep school system; higher education was the focus of everyone’s attention, and the right college was everyone’s goal. There were families in my town that bribed their kids with cars if they got a good score on the SAT. There was a family that had a ranking system of cars as part of the bribe: hit this score and you get this car; hit that score and you get the BMW. I am not kidding.

We had four valedictorians in my graduating class. Four. And they all had to make speeches. Because of course they did.

I don’t remember a single word that any of those four lovelies spoke; all I remember is that the sound system was shot, and there was a van parked next to the podium, with a couple of big guys crawling around trying to fix the microphones. It did not occur to me at the time that those guys were performing a more important service than the four, smug students who were making speeches about things they knew nothing about.

The idea that someone might not get into college was just…unheard of. Un-thought of. There was an unspoken understanding that if you got yourself into the Right School, everything else would flow like the sweet waters of heavenly justice.

I think.

I’m guessing here; no one ever said those words around me. I think my town was so over-represented by the Professional Class that the glide-path from high school to college to grad school to some kind of career was just assumed.

There are certain things in your culture or class that are so universally understood that they never have to be spoken—and those are precisely the things that can fuck you up.

I did not have excellent grades. I had good grades in the classes I loved, mediocre grades in the classes I liked, and rotten grades in math and science (and French, though for some insane reason, I kept taking it long after I had to). My grade-point average was average, but I was a good writer, and I seemed to show some Leadership Potential in my chosen extra-curricular activity, so I got into some good schools. More than I had any right to, probably.

When I say “more…”

In my town, it was standard practice to apply to many colleges—seven, eight, nine, whatever. And this was before you could access the Common Application online, or type in a PDF form, or anything like that. Every application had to be handwritten or hand typed. When I got to college and found out that kids from other parts of the country had applied to only two or three schools, I thought they were all crazy. Eventually, I realized that I had been the crazy one. But it took a while.

I have no regrets about my liberal arts college experience, as I wrote about recently. But it’s inescapably true that no one engaged me in a discussion about what was going to come after. Not one person, ever.

In this, I was clearly an outlier. It was 1985, and everyone had a plan. Everyone. Even the kids who were doing theater with me had post-graduate plans—for law school, or business school, or some PhD program somewhere. Everyone knew what was coming next but me.

Not quite as bad as Dean Wormer’s admonition to young Flounder, but…close.

How Pathy Was My Path?It’s not like I hadn’t thought about it. Of course I had. I had decided that theater was going to be my thing, which made the whole idea of a “career path” kind of fuzzy. How did one get a career in writing or directing? By…just doing it, I figured. So, I did as much of it as I could. Meanwhile, I tended bar (very briefly), I worked in a bookstore (for a year), and, eventually, I taught school. These were all merely “day jobs,” ways to make money while I pursued my dream. A temporary state of affairs that went on for about 15 years.

Here’s what I learned from those 15 years: I learned that you could make things happen through your own sweat and effort, but that making a thing happen once was no guarantee that a thing would happen twice, or ever again. The world was willing to let me raise money and bring people together to stage a play, but once that play closed, it was back to square one. I had no more money for round two than I had started with in round one; I had no more reputation, either. Anything I did was a drop in an enormous ocean. Getting someone else to stage a play I had just mounted was a game whose rules seemed arbitrary and changeable.

I received some lovely rejection letters. Even when people thought my work was good, it wasn’t quite what was wanted. Other, more talented people prospered. Less talented people prospered, too. People who had friends in the right places prospered. People whose work focused on a currently hot topic. People who wrote from the perspective of a previously silenced group. Everybody but me, it seemed. I could tell I was getting resentful and peevish about it all, as though The Arts owed me a living. As though anyone did.

Did I hustle? Did I grind it out to try to get ahead? At the time, I thought I was doing that. I sent plays and synopses and query letters to agents and theaters all across the country. Real letters, printed out and folded and stuffed and stamped. I followed up on each letter without becoming a pest. I thought that was hustling.

What I didn’t do was get out of the bubble of my little theater company and schmooze. I didn’t network. I didn’t work the room. I didn’t make myself known and wanted and indispensable in the larger community. Frankly, I didn’t know how. In our company and among my friends, I was the writer in a sea of actors—the token introvert—the guy who disappeared from parties after an hour and slunk home in silence. That guy. I played that role well, but I didn’t know how to get cast in it in other productions.

So, Fine: Be a TeacherPart of the time while I was working with my little theater company, I taught high school English. If I gave up on theater, I could always focus on teaching. It was a profession! Just the kind of thing my old hometown would have wanted me to pursue, right?

Wrong. I went to a high school reunion at some point early on, and I discovered that literally no one in my graduating class was involved in education at any level. They had been trained since birth to start strong and never stop climbing. And when you’re a teacher, well…

Do you know what you get if you’re a brilliant teacher in a public school, a really first-rate teacher, with greater instructional skills than your peers, and a stronger work ethic, and a greater dedication to your students than anyone else in your school (not that I was any of those things)?

Nothing. You get nothing.

Well, that’s not true—you get satisfaction. You get a martyr’s sense of mission. You are invited to kill yourself for the sake of others, and you will be told that it is a great and noble thing. Which it absolutely is. But what you won’t get is a raise or a promotion based on your effort. Those things don’t exist in public school, and you will be shamed for even thinking about them.

Raises? Public schools tend to be union shops, where salary levels are fixed and immutable. If you have an advanced degree, you’ll make more money. If you have more years in the system, you’ll make more money. And that’s it. Performance has no bearing. The very idea of “performance” in that world lies somewhere between strange and disreputable.

Promotion? There’s no such thing as a “promotion” in most schools. Maybe there’s a senior teacher role, or a department chair role. Often not. In most cases, a teacher is just a teacher. If you want to do better for yourself and your family, your only road up is out of the classroom into administration.

By the age of 30, everything in my work-life had taught me that when it came to external rewards, it didn’t matter and was never going to matter how hard I worked. I could feel pride in what I did and satisfaction in its effect on audience members or students—and those things mattered quite a lot—but monetary success would always be controlled by strange and arbitrary forces beyond my understanding—and it was dirty and shameful of me to be concerned with those things, anyway.

I lived reasonably comfortably within that reality for a while. And then I got married, and a few years later, we had a child. And it was time to take another path.

So, Fine: Get a Regular JobWhen I started working in Corporate America: Education Division, I was shocked to learn a number of things: I could leave my desk to go to the bathroom, get a cup of coffee, or schmooze with a colleague pretty much whenever I wanted to. I could leave a room without asking for permission! This was unreasonably pleasing and surprising to me.

Also: I could do good and meaningful work that benefitted students and teachers, even though I worked for a company rather than a school. I could work for people who believed in “doing well by doing good.” To be sure, that wasn’t always the case; there were other places and other people where a sense of mission was sorely lacking or was just lip-service. But sometimes, in some places, everything clicked.

Also: if I worked hard and the company did well, I could get raises and occasionally bonuses. That didn’t suck, since I was trying to raise a family and was sometimes the only breadwinner.

Were the Curriculum world or the Virtual Ed world or the EdTech world true meritocracies? Weeeelllll….you know…..of course not. But they felt more meritocratic than any place I had worked before.

I started my post-theater and post-teaching career in a very small division of a very large company, and as the division grew, I was able to rise within it. I learned how to ask for what I wanted and hustle for it—certainly more than I ever did, writing letters into the void.

Why was I able to do that for other people’s products and not my own writing? Why is that still the case, even now? I don’t know.

I do know that many of the skills I have used in my corporate jobs, I learned by doing theater—as I’ve written here. If I understand curriculum, it’s because I understood storytelling and holding the attention of an audience. If I understand team management, it’s because I produced and directed plays, and worked under a variety of directors (good and bad) to watch how they did it.

Is this the realm where I thought those skills would pay off? It is not. But when I look back at my path in life—a path I never saw laid out in front of me, but which I can see clearly now behind me, it almost looks like it was inevitable.

Almost.

November 7, 2025

Books Make the Best Gifts!

Winter is coming. The holidays will soon be upon us. As the days get shorter and darker, our loved ones will need reminding that they are, indeed, loved in this cold, old world. And do you know what’s perfect for communicating that—besides the warmth of your love and friendship, I mean?

A BOOK.

Did you know that I’ve written three mystery novels and a new techno thriller (for lack of a better descriptor)? Have you read any of them? Have you read all of them?

They’re available at Amazon in paperback and Kindle formats. If you like my non-fiction writing here—and/or if you like mysteries—and/or if you like character-driven stories with a strong sense of place—perhaps you might enjoy my books.

The three mysteries follow a slacker jazz musician named Jordan Greenblatt (the least film-noir detective name imaginable, for the least noir-ish hero I was able to imagine), who lives in a low-key, artsy neighborhood of Atlanta, Georgia and who aspires to not much beyond hanging out on his porch with his bandmates, his college friends, and his wife. He supports his music habit by doing uninteresting, un-dangerous, investigative work…until he wades into waters that are way over his head.

The books are sequential, but I think (and have been told) that they work just find as stand-alone stories.

Here’s a little bit about each, with links in the titles:

Jordan Greenblatt deals with life the way he deals with music—as a supporting player. Jordan is the bass guitar in the band of life—steady, solid, able to keep his cool, emotionally detached. Even as a private investigator, Jordan keeps a low profile. He takes pictures of adulterous husbands and helps local lawyers with medical malpractice cases, but he rarely breaks a sweat. And then, one steamy summer day, Jordan agrees to look into an old hit-and-run accident that took the life of a girl he knew in high school—a case in which he has a personal stake, for once in his life. The more he looks into the story, the more he is forced to question everyone’s assumptions. Bit by bit, he is dragged deeper and deeper into a mystery that he is not prepared to handle—a mystery that threatens to uncover many closely-guarded and long-protected secrets—including his own.

Jordan Greenblatt thought he had put diva drama and bad choices behind him a long time ago. But when a worried theater student comes to him for advice, it sets off a chain of events that leads Jordan back to his old college campus, working undercover to find a dangerously addictive new drug and the students or staff members who might be selling it. Leaving his regular life behind, Jordan tries to solve a puzzle and save a life without losing himself in the bargain. The longer he stays, the more he wonders if he can get the answers he needs and find his way back home.

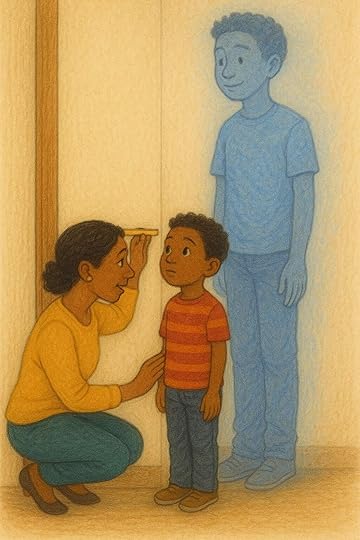

Bill and Robinette Tomlinson think their prayers have been answered when they bring two foster children into their suburban Atlanta home. But when the birth mother is released from jail and fights to get her children back, the kids don’t just move away; they disappear. And so does the mother. And soon, so does Bill. Unsure what to do, Robinette turns for help to her college friend, Jordan Greenblatt, recently retired as a private investigator. What starts as a simple favor for a friend turns into a deadly search through small, South Georgia towns and the darkest recesses of the Internet. What kind of web has trapped Bill and the children—and can Jordan untangle it in time to save them?

And now there’s my newest book, Box of Night. It’s a little bit mystery, a little bit science-fiction, a little bit dystopian thought experiment:

When a tech visionary dies under unusual circumstances, a fixer named Fox is pulled from his quiet country exile into the heart of a high-stakes mystery. A prototype is missing. The code has been wiped. The only clue is a trail of stories about an experimental neural interface that promises not just immersion, but total sensory substitution. As Fox investigates, he uncovers a world where reality is a negotiable concept and the game you’re playing might just be playing you

So, there you have it. Four books you can give as gifts to your bookish friends, while supporting an independent writer who is operating out here entirely on his own, sans agent, sans publisher, sans anything.

I hope you’ll consider one (or more!) of the books as a gift for one (or more!) of your loved ones this season. And if you do…THANK YOU!

November 1, 2025

A Theater of Presence

A team performs at Washington Improv Theater

In the middle of my senior year of college, while I was having fun doing theater with my friends and doing a poor job of thinking about the future, a depressing article by film critic, David Denby, was published in The Atlantic, talking about how he—a non-theater person—had attempted to see more plays and understand their power and their attraction. It hadn’t worked. He had utterly failed to understand why anyone would like theater as an art form or a storytelling medium. It left him cold.

He was raised on film, you see, and he found film a far more compelling and immersive medium, one which had the power to create realistic worlds. Not having grown up within the conventions of theatergoing, he found live performance weird and silly and a little embarrassing.

To say that the article bothered me is an understatement. I have remembered its effect on me for 40 years, without ever going to look for it again (until now). I’ve linked to it, above, but I’m not sure I want to re-read it.

It bothered me, but…I actually found his argument convincing—IF you limited it to the world of realism and naturalism. Yes, a living room set on a theater stage will never feel as convincingly real to an audience as a living room scene captured on film. Yes, everything on stage will feel symbolic and actor-y and freighted with meaning, in ways that movie acting rarely does.

AND YET. At the time, I also rejected his argument, because I already knew that theater could be much more than a second-best rendering of living-room reality. When a new medium is invented, old artists have to adjust. When photography became popular, painters had learn how to do more than try to imitate reality. Some of them didn’t bother; they continued to paint landscapes and portraits. But others experimented with light and form and color and shape to see “reality” in very non-photographic ways—and it is their work that we talk about.

Theater can definitely do that—and it has, for decades. But does it matter?

Maybe it’s about to, in a way it never has before.

Every action has an equal and opposite reaction. That’s not my opinion; that’s the law, and I’m starting to see it play out with technology among my kids’ generation. Inundated with Smartphones and streaming media and computer-generated special effects, a lot of them seem to be craving something more tangible—more “real.” Suddenly, vinyl records are back in fashion. Suddenly, typewriters are kind of cool. Substack may be growing, but so is a return to paper-based ‘zines. What’s next?

Well, if we’re about to have an AI-generated actress foisted upon us to join the kaiju and monsters and superheroes that populate our screens, maybe kids will start seeking out a storytelling medium that they can touch—something that was built to talk to them in a human way, on a human level—something that will hear them when they talk back.

“I’m not real, and neither is my coffee.”

A play can’t speak to millions of people simultaneously, and maybe that can be its strength now. Maybe what we need is to be in smaller rooms, watching and listening together, attending to something that’s actually happening in front of us.

Another author from back in the 1980s saw this coming from miles away. George W.S. Trow wrote an essay in the New Yorker magazine called, “Within the Context of No Context,” which was republished with a new forward as a book in 1997. He was looking at the effects of television and tabloids, but everything he worried about back then has only gotten worse.

In his essay, Trow talks about how the middle-ground of public life has decayed, leaving only things meant for everybody and things meant just for you. What has been lost is a sense of community—of smaller-scaled things built by and intended for a more intimate “us,” that is more than just “me.”

Two grids remained. The grid of two hundred million and the grid of intimacy. Everything else fell into disuse. There was a national life—a shimmer of national life—and intimate life. The distance between these two grids was very great. The distance was very frightening. People did not want to measure it. People began to lose a sense of what distance was and of what the usefulness of distance might be.

Trow nails it, long before the advent of streaming and doomscrolling. In Hollywood, they talk about trying to produce “four quadrant” movies that can appeal to every single demographic and suck up every single dollar possible. That is the grid of the two hundred million. And even though “television” is no longer as monolithic as it was when I was a child, or when Trow was writing about it, it still aims at millions.

Who tells stories meant only for thousands—or hundreds—or a single auditorium?

When I was living in Atlanta and working at a regional theater, I belonged to a group called Alternate Roots, which brought together a wide variety of performing artists who all felt a sense of community-based mission in their work. To join the organization, you had to stand in front of the membership and talk about your work—what community it grew out of and what community it was meant to serve. It could be a physical community, like your town or your region; it could be a religious or spiritual community; it could be an ethnic or sexual or gender community—it didn’t matter. But you had to have a sense of rooted-ness; you had to know who was feeding you and who you were trying to feed.

I loved the people in that group, and I enjoyed their enormous annual get-togethers that combined business meetings with workshops and performances and communal cooking and a fair amount of late night drum-circling. I loved the people, but I never really felt like I fit in or knew my place. I was trying to understand myself as a playwright, but I never knew how to answer their Big Question: who was my community?

I didn’t have one. I was just trying to write whatever interested me.

“Community theater” gets a bad rap sometimes. It’s not “professional.” It can be amateurish, or inept, or raw, or cringey. But it can also be warm, and loving, and wonderful—because we know everyone up on stage, and we know what part they played in the last show, and we know what they’re going to do next, because they told us when we saw them this morning at Starbucks.

But it also gets a bad rap because community theater often mounts plays that have been done many times before, in more professional settings. We go see our friends in the 99th iteration of “Grease,” and…ok. OK. We love them, and it’s fun to see them and support them, but even as cotton candy, how many more performance of “Grease” do we really need to see?

When I think about the need for something between the grid of two hundred million and the grid of intimacy—about the need for something tangible and meaningful—real people speaking to us about real things that matter to us—isn’t there room for something else that could be called community theater?

What would that look like?

It could be the same kinds of people who perform now, coming together to write and perform plays about the communities they live in and the issues they’re facing. Those could still be musicals—or farces—or plays in verse—or tragedies. It wouldn’t have to be super-serious. It wouldn’t have to be dreary. And it wouldn’t necessarily have to be quiet. Maybe it would encourage people to stick around after the play to talk and argue. Maybe it would encourage people to talk back at the actors on stage in mid-performance.

There may be people out there, all over the country, doing exactly that right now, who we don’t know about. Maybe we don’t have to; they’re not here for us.

Just as painting evolved to capture reality in ways that photography couldn’t, theater can evolve to bring dramatic storytelling to people in ways that movies or television can’t. And it already has. None of this new. It’s been done for over a hundred years, in a variety of ways, by various avant garde artists and groups all over the world. But maybe it’s time to make those things a little less arty and rarified, and bring them out to our friends and neighbors—to say: Hey, it’s just us here, together in the dark. Let’s talk about what’s going on. Let’s say what needs to be said—by us and for us.

Something real, like the coffee I’ll be buying from the actors tomorrow.

October 25, 2025

[2025 Re-Post] Rigor Shouldn't Lead to Mortis

I have been in lockdown for the past two weeks, working on assessment items for an academic Olympiad and trying to help both an LLM and a team of human subject-matter experts get better at crafting questions that demand high levels of cognitive skill…more rigorous items, if you will. And since I don’t have time to write anything new this week, and the idea of rigor is front-of-mind, I thought I’d re-share this post from two years ago.

The Challenge

Once upon a time, I attended a meeting of Chicago teachers, back when Arne Duncan was CEO of the public school system there. He was advocating a new plan for a standardized but somewhat decentralized curriculum (schools could select programs from a menu of approved vendors), and he was talking up how this plan would increase academic rigor. Whereupon, some teacher in the crowd stood up and yelled at Duncan that the CEO had no idea what “rigor” actually meant, and neither did anyone else in the room, and if anyone thought they did know, it was a good bet their definition wasn’t shared by anyone else in the district, or in the education world more widely.

I don’t remember what Duncan’s response to the heckler was. It was probably ham-fisted and vague and ineffectual—which would not be surprising. Rigor is one of those words that people love to toss around without really knowing what it means. As Supreme Court Justice, Potter Stewart, famously said of obscenity, we know it when we see it. As pretty much everyone has said of beauty, it’s in the eye of the beholder. But should it be? Must it be?

A Healthy Workout

The easiest (and dumbest) way to think about rigor is in terms of quantity: just give kids more to do. I say it’s the dumbest because, if students are doing a certain amount of X successfully, it’s not rigorous to simply do more X. It’s not even particularly helpful. It’s just tedious.

If a trainer is going to put me on a rigorous workout regimen, is he going to have me lift the same amount weight every day, forever, just adding more and more reps? He is not. I’m sure there’s probably some benefit to adding reps to your current weight-load. Stamina? I don’t know; I’m not a trainer. but if you’re trying to build muscle, people tell me, you have to lift increasingly more weight. The lift has to get harder over time. You lift what’s just doable, and you work on that for a while, until it becomes easier. Then you add more.

Even the least gym-ratty among us should be able to recognize what’s going on here. In edu-speak, we call it the Zone of Proximal Development, or ZPD. It’s that sweet spot—Goldilocks’ “Just Right” place—the most difficult level of work that a student can do comfortably. It’s where we would like every day’s classwork to be situated, for every single student. Difficult to do, when every student is in a different Just Right place. And more difficult still when, like the guy lifting weights in the gym, today’s Just Right place changes over time. To maintain rigor, you have to know exactly where a student is, and situate the work right at the leading edge of that ZPD. It’s a serious challenge.

What Matters Most

What does it mean to know “where a student is?” In math (and sometimes science), you can assess knowledge or mastery of discrete topics and skills. In the humanities, which is less modular and discrete, it can be trickier. Once you can read at a high Lexile level, you’re a skilled reader. Once you can write at a collegiate level (or close to it), you’re a skilled writer. What constitutes “harder?”

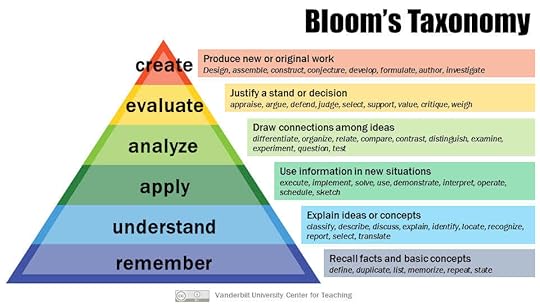

When we want to increase rigor and push students to go further, we often increase the cognitive complexity rather than just accelerating them to the next topic. Benjamin Bloom’s taxonomy provides a handy guideline for teachers, showing factual comprehension as a base level, and working up through analysis to evaluation and, ultimately, creation of new content. This can help teachers take the same set of content and change what kind of work is expected of each student.

Richard Strong, Harvey Silver, and Matthew Perini, in Teaching What Matters Most (ASCD, 2001), go further , describing rigor as, “the capacity to understand content that is complex, ambiguous, provocative, and personally or emotionally challenging” (p. 7). It’s an interesting construction. The authors aren’t satisfied with mere complexity. They want students to be able to handle ambiguity and provocation—not merely theoretical provocation, but material that challenges the student personally.

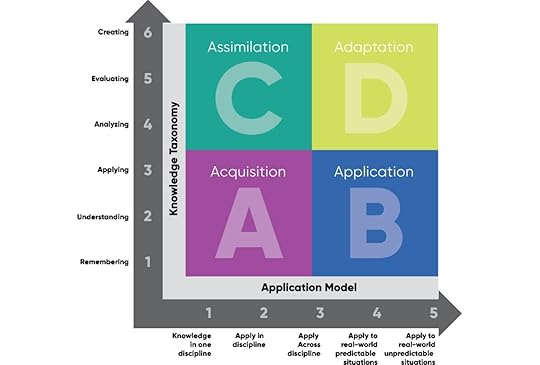

Ambiguity is also an important element of the Rigor-Relevance Framework, developed by Bill Daggett. The framework creates a quadrant map, with Bloom’s Taxonomy forming the vertical axis, showing increasing cognitive complexity, set against a horizontal axis that speaks to application—starting with knowledge and use within one classroom discipline, then moving to application across disciplines, then going outside the classroom into real-world but clear and predictable situations, and landing, finally, at real-world application in a messy, unpredictable situation. For Daggett, real rigor is the ability to work at the highest cognitive levels (evaluation and creation), in the messiest and most ambiguous contexts.

Getting Stronger Every Day

What is the result of a rigorous physical workout regimen, sustained over time? You build muscle. Your body changes. It is no longer what it was. If we worked with a trainer for a year and saw no physical change in ourselves, we would be dissatisfied.

What is the result of a rigorous education, sustained over time? You build mind. Your thoughts change, and the way you think changes. You are no longer what you were. If the child moves from one grade to the next and has not grown and changed in what she knows and how she thinks, even a little, parents should not be satisfied.

And yet, it’s exactly that kind of growth and change that has been the focus of parents’ ire and activism in recent years. God forbid the school should provide opportunities for students to challenge their preconceptions, to broaden their understanding of how the world works. Somehow, we’ve been led (or forced) to believe that what a child thinks and how a child thinks are…none of our business as teachers. That the content of a child’s mind is the sole responsibility of the home and the church, and that the school’s job is merely to reinforce and strengthen whatever ideas and opinions the child comes in with. Apparently, we are supposed to provide a variety of safely vetted facts, and hone a variety of state-mandated skills, but we must ensure that the child never actually changes her mind or her opinion about any of those facts, or applies those skills to develop her own ideas.

This is dangerous nonsense. A nation that is afraid of looking at things from a different angle, considering things from a different perspective—is a nation that is calcifying. A community that is afraid of its children learning facts that their parents might not have learned, or developing opinions different from those of the adults—is a community that is frightened by a changing world (which is the only world we have).

We are better than that. Or, rather, we should be better than that. If we want our children to inherit a strong and dynamic country, we must be better than that.

October 17, 2025

The Still, Small Voice

I’ve always thought of myself as the quiet type—the guy at the corner table, nursing his bourbon and watching the world go by, wry commentary running through his head. The guy who lives by Lao Tzu’s dictum that those who know do not speak, while those who speak do not know.

And I’ve been that guy. Sort of. I probably still am, on those rare occasions when I find myself entirely alone. But that wry, running commentary? It’s not exactly quiet. And it never ends. So…do you really qualify as one of “those who do not speak” if you can’t stop speaking to yourself?

I’ve tried meditation a few times, and I’ve never gotten the hang of it. It’s a shame. Emptying my mind seems like it would be a great idea in theory, because man, does it get noisy up in here.

Put the inner monologue to the side for a moment. There’s usually a piece of music running on a loop in my head. Sometimes it’s a theme from a piece of classical music (lately it’s been a couple of minutes of Beethoven’s 7th Symphony, first movement); sometimes it’s a song I love. Sometimes it’s a song I hate, which is really annoying and very hard to get rid of. Whatever it might be, if I’m not engaged in active conversation with someone, there’s usually some kind of tune playing in my head.

Unless I’m listening to actual music in the room, which I’m doing more and more frequently because of my tinnitus. More noise in the head-bone.

And, as I mentioned, if I’m not talking to people in person or on Zoom or on Teams, I’m talking to myself—that running internal monologue that, I was surprised to learn, not everybody has.

I’ve always thought of myself as a good listener, but…I don’t know. How much can I really be paying attention to you if I’m constantly talking to myself?

Having a Model HelpsI was thinking about all of this recently because our little division within my company needs to plan some sales training in a few months, and one of the topics we wanted to spend time on was consultative listening—the need to listen to the customer, ask them questions, explore their problems, and only then start to offer solutions (rather than banging on the door and telling them what a great vacuum cleaner you’re selling…metaphorically speaking).

I remember being in discussions like this 20 years ago at another company. I was leading a curriculum team, and my project managers were going to have to go out in the field to work with focus groups and content review teams at school districts. My folks were all former classroom teachers; they had no experience representing the project requirements and deadlines of a company to a client, or the concerns of a client back to the company. So, we were invited to sit in on a training with the sales team, and this idea of consultative listening was exactly what we were taught.

They gave us an acronym to use, which I remember to this day: LAER, for Listen, Acknowledge, Explore, and Respond. We learned it, we practiced it, and we got a lot of humiliating feedback—because all of us tried to get to Respond too fast. We so desperately wanted to be of use, to be helpful, to be problem-solvers. But we had to learn to back off, to ask questions, to listen, and then to ask more questions.

You might think that former classroom teachers would be well positioned to be good questioners and good listeners, but it’s not always the case. We often default to talking—partly because we think it’s our job to impart wisdom (cover that curriculum!), and partly to fill the void when all we’re met with is blank stares.

Even when we shut up and listen to a student answer a question, we’re often not listening to them—not really. We’re just waiting for the correct answer that we already know. If we don’t hear it, we move on to the next kid. We may not have actually heard what that first student said.

We could pause. We should pause. We could acknowledge (“what I hear you saying is…”, and we could explore (“how did you come up with that answer?”). We would learn a lot about how our students are thinking, and why they make the mistakes they do. We’d be better teachers if we were better learners—if we were better students of who our students were.

What My People SayThe importance of listening is pretty central to my ethnic/religious/cultural background. The most important daily prayer in Judaism starts with, “Hear, O Israel: The Lord our God, the Lord is one.” LISTEN UP, PEOPLE!

Throughout the Hebrew Bible, God is always heard, never seen. A voice speaks out of a burning bush, or a voice thunders out the law from the top of Mount Sinai (and frightens everyone back to their tents), or a voice whispers prophecy to those who are able to hear it:

But the Lord was not in the wind: and after the wind an earthquake; but the Lord was not in the earthquake: And after the earthquake a fire; but the Lord was not in the fire: and after the fire a still small voice.

(1 Kings 19:11)

Which is all kind of funny, since one thing we modern Jews are famous for, at least in this country, is never shutting up. We interrupt each other (and innocent bystanders) constantly, and we don’t even do it to be rude. It’s so common a thing that it has a name: Cooperative overlapping.

Let me tell you, there’s not much room for a still, small voice when my cousins get together.

Other folks may not interrupt each other vocally, but we’re all checking out of conversations, these days, by looking at our phones “just for a sec.” We get a beep, and we need to check a text. Or look at one little TikTok that someone sent us. But it’s never just a sec, and it’s never just one video, and once we start scrolling, we’ve lost all sense of time, and the world continues turning around us.

With the constant yammer of social media, you’d think we’d be better readers and listeners. There’s so much to read and listen to, now! But somehow, the more stuff there is out there, the more rigid our biases and preconceptions seem to become. The arrow of science starts with gathering evidence and ends with forming a theory, but the arrow of 21st century America seems to start with theory and then go searching for confirming evidence.

Someone is KnockingI am trying to do better. I am trying to hear more voices and let them have some space in my crowded head, even if I disagree with them. Even if some of them are scary. I want to understand. I can’t be of use to anyone—or myself—if I can’t understand.

I am trying to shut up the inner monologue and be more present among the people I care about. It’s always better. There is nothing I love as much as being at that corner table with friends, cooperatively overlapping with stories and laughter and memories.

Come find me there and tell me how you’re doing. I’ll listen.

October 10, 2025

1994

Today is my birthday.

I like my birthday. I like the October-ness of it, I like the symmetrical 10/10-ness of it—I enjoy the fact of it, all around. I am not a subscriber to the Patton Oswalt theory of extremely limited celebrations. Life is hard enough—you should celebrate what you can, when you can.

I don’t make a fuss about my birthday or ask anyone to do anything about it, really, but being stupidly passive aggressive, I will feel lousy if nobody notices or says anything. It’s a character flaw, and I definitely plan to work on it. Eventually, One of these years.

Assuming I have years.

Is that a reasonable thing to assume? I’m 62 today. I’m reasonably healthy, but…you know. My mother didn’t make it to 62, although her mother made it into her 90s, as did that grandmother’s father. My father is still going at 88. Pick a number and put your money down.

Sixty-two. It’s hard to believe. I don’t feel the years most of the time—certainly not as many as the calendar claims. I don’t feel much different from how I felt ten years ago, or even 20 (most of the time). I don’t think I look like whatever I thought this age looked like, back when I saw it from the perspective of youth. But I’m probably lying to myself.

Regardless, it’s been a long time.

I thought it might be interesting, as a little memory exercise, to cut the present number in half and see where I was and what I was doing, half a lifetime ago.

That would be the year 1994, when I was turning 31. Let’s see what I was up to.

LivingI was living in Greenwich Village, on Christopher Street, in an apartment I shared platonically with a beautiful redhead named Mandy. I had moved to New York a year earlier, freshly divorced and about to turn 30. I had put myself, my friends, and my family through a lot of drama and pain, the year before that—trying to understand what it was I wanted in life and love, trying to figure out whether I was at least on the right path, trying to figure out what step to take, and in what direction, and whether I had the courage to take a giant step in any direction.

After a prolonged spell of self-imposed exile in Eastern Europe, I had come home to Atlanta, gotten divorced, moved to New York City to do theatre with my friends, and turned 30. It was a lot of Big Stressors all bundled up together, but it somehow felt easier than spacing them out over endless months, And in the end, I had more or less survived to start something new.

Mandy and I weren’t close friends at the time we moved in together, but we were working together in our little theatre company, and we were both looking for a place to live. Plus, she seemed to find it amusing to be able to tell her parents that she was moving in with a 30-year-old, divorced playwright.

It wasn’t a big apartment, but it had two bedrooms and a living room large enough for Mandy to assemble and store the insane props that our theater productions required, including a 20-foot-long processional carpet made of stitched-together baby clothes dyed blood-red, and also a big, brass, 19th century chamber pot.

The living room looked down onto Christopher Street, right across from the Lucille Lortel Theater. That made our fire escape prime real estate for viewing big events like the Halloween parade, during which our apartment became public property for every performance artist we knew.

The layout of our place made it pretty clear that there had once been fewer, bigger apartments in the old building. One of the bedrooms still had the old, vintage, tin ceiling. The rest of the place had lost that decoration. At some point, someone had tried to make up for it by plastering thick, gold wallpaper on the living room ceiling. One summer, the intense humidity melted the glue, and it all started coming down in strips. We tried stapling it back in place, which looked terrible and worked badly. Eventually we tore it all down, leaving surreal swirls of dried, red glue in its place.

We were young and poor, so we did the best we could with the place. I brought a papasan chair to the apartment, and Mandy brought a papasan couch. That was the sum total of our living room furniture.

We had a Jamaican building manager named Vandalay, who I remember talking to me face to face only once (he usually just yelled at people through his door). The reason he emerged to speak to me was that some of our bathroom tiles had fallen off into the bathtub. He yelled at me that it was all my fault, for letting the shower water hit the walls, because water, as I should have known, was very, very powerful. He lectured me about this while angrily regrouting the tub.

Yes, you can grout angrily. I stand by that adverb.

WorkingEvery morning, I would walk or take the bus from the West Village to the East Village, to get to my school on East 12th Street and Avenue A. It was a small magnet school, then in its third year of existence, and it was housed on two floors of a gigantic public school building. We tried to feel reform-y and different, but it was a little challenging, being inside such a giant institution and having to make use of all of their facilities.

I taught a combined 7th and 8th grade Humanities class on a block schedule, meaning I taught two double-sized periods, with a 90-minute advisory period at the end of the day.

If you’ve never had to handle 7th grade boys and 8th grade girls in the same room, count yourself lucky, because they are barely the same species. The girls were fully teenagers, and the boys were strange shape-shifters—tweens one minute and little children the next.

The curriculum for the Humanities class was meant to be created and overseen by the four teachers who taught it: two English teachers and two history teachers. We were given an extra-long planning period once a week to share ideas and resources, and to hold ourselves accountable to some kind of plan. Unfortunately, about halfway through the year, there was some kind of conflict and disagreement that led us to stop planning together or even meeting together, and after that it was every man for himself.

The upside of going it alone: a longer lunch period, once a week, for extended trips to a nearby Polish restaurant for split-pea soup and kashka varnishkes. The downside: no one had any clue about, or control over, what the four of us were teaching. And I, personally, had very little clue about anything.

The advisory period had no curriculum at all, by design. I was allowed to do pretty much whatever I felt was needed with my group of 16 advisees, including taking them out of school if I thought they could be trusted. If the weather was nice, we usually went down to Tomkins Square Park so they could play basketball or laze around at the end of the school day. It was a very human and lovely way to spend time with my kids.

PlayingAfter school, I’d go home and correct papers, try to write, and perhaps sleep for a bit. Then it was right back to the East Village, where our little theater company rehearsed plays in church meeting rooms and other odd spaces, after which we’d go to the Tile Bar on 1st Avenue to drink, far too late into the night.

In 1994, we were still performing wherever we could find a space to rent. We had not yet established a residency at a theater; that would come later and last for several years. In 1994, we were rehearsing a version of Lysistrata that I had written for the company, to be performed at the Ohio Theater on Wooster Street. It was a Greek comedy follow-up to the modern adaptation of Agamemnon that we had done the previous spring. Agamemnon had been the reason for the red carpet made of baby clothes.

My version of the comedy, called Sister Strata, was set during the American Civil War, with Union and Confederate women banding together to launch a sex strike to stop the war and free the slaves. It was silly and slapstick-y (hence the chamber pot), and not quite as funny as we had hoped (in spite of the chamber pot), but it had some great songs and a climactic scene I had stolen shamelessly from the movie, Shenandoah.

We were a tight little company of friends, as many small theater companies are—and like many such groups, we were in each other’s lives completely and possibly too much. Most of the time, I didn’t mind. These were the people I had come to New York to be with and make art with. I didn’t socialize with anyone from the school where I taught; this group was it. If I was going to ride my bike (perilously) up 6th Avenue on a lovely Saturday afternoon to hang out in Central Park, it was with them. If I was going to go out at night to hit the Indian restaurants on East 6th Street, it was with them. If I was going to hang out with people in someone’s apartment, applying facial masks to each other semi-ironically and singing along with Salt N Pepa songs, it was with them.

Did it all get too close and too intense sometimes? Sure. But sometimes it was exactly the kind of closeness and intensity I needed, being the introverted, live-inside-my-head kind of person I was. They were the actors; I was the writer. I spent far too much time on the sidelines, watching and listening and taking notes.

Somewhere in there, I flew out to Los Angeles to see rehearsals for another play of mine—the one for which this Substack is named. It was one of the very few times that anyone other than my own company produced one of my plays, and it was exciting to go back to LA, where I had gone to graduate school, and to watch rehearsals like a Real Playwright.

LovingWhile out there, I got to see some old friends, including a former girlfriend who took me out to see a production of Steve Martin’s play, Picasso at the Lapin Agile. It was a lovely and fun night, and when I got back home to New York, this former girlfriend mailed me a computer disk with free software on it for a thing called AOL, which would let me, if I plugged my computer into the phone jack in my apartment, type-chat with her at night when I got home from rehearsals. We ended up chatting nearly every night.

Later that year, she would fly out to surprise me for opening night of my adaptation of the Epic of Gilgamesh, and I would kiss her in the stairwell of the theater.

That summer, she moved to New York City. We’ve been together ever since.

DreamingBut that was all still to come. In the fall of 1994, I was still alone and often lonely in my crowd of friends, still pushing the boulder of art up the mountain of indifference, hoping to reach some kind of stable peak that would tell me I had made the right decisions in my life. I didn’t know yet that the peak didn’t exist—not for me, anyway—that the rock would roll back down to sea level, show after show after show. I didn’t know that within three years, the members of our little company would drift apart and move on to other things in life. I didn’t know that I would re-marry, and become a father, and leave theater behind me—something I couldn’t have imagined, back then.

Would I want to alert my young self, if I could go back in time and talk to him? Would I want to grab him by the shoulders, and shake him, and say, “Give it up, kid. It’s not going to amount to anything. Stop wasting your time”?

No, I don’t think so. There’s nothing I am today that doesn’t have its roots in what I did back then—the teaching, the writing, the company-running, the longing. All of it mattered. And the work we did together was good work. We didn’t perform for millions, but we served our small audiences well during our brief lifespan, and they seemed to appreciate and care about the plays we performed for them. We served them, and they supported us. We built a little community. And that’s the gig, whether you play to tens or to millions.

No, I wouldn’t try to stop that young man. Let him keep dreaming, and writing, and working. Let him keep sitting in dingy rehearsal rooms and nursing drinks at dive bars. Let him despair at ever finding love, or giving love, or being seen, or accomplishing something worthwhile. Those things will come. He doesn’t know it yet, and those things won’t be what he expects them to be, or what he wants them to be, or even what he needs them to be.

But he doesn’t need to know that yet. It will all come to him in time.

Friendly Reminder:

My new book, Box of Night, is available in paperback and Kindle eBook formats here. A little bit mystery, a little bit science-fiction, a little bit dystopian thought experiment. I hope you’ll give it a try.

If you do, and you enjoy it, let me know. And if you really like, it, please write a review at Amazon or Goodreads. Every little bit helps.

October 3, 2025

The House on Rattlesnake Mountain Road

If you drive north on Prospect Hill Road from the town of Stockbridge, Massachusetts, and turn right onto Rattlesnake Mountain Road, you will not be able to see the house that my father helped design. A row of pine trees that he and I planted along the driveway over 40 years ago hides the house from view.

It doesn’t feel like that many years to me, but the trees say different. Trees mark the time better than I can.