August and Archives

When I was weeks away from finishing the book, I went into the computer lab at my graduate school to print off something. It’s a small room and usually not that many people are there. But that day, I ran into one of the second year thesis students and she and I started to talk for a bit. We were both TAing the same class and would see one another at lectures, so I had gotten to know that even though she was only about four years older than me, she already had two daughters. She was also pregnant during her undergrad and visibly so while in classes. When I ran into her this day, we talked about how sometimes our physical bodies were completely ignored by people and in conversation, especially within academia. She related this to being pregnant, while I was more so thinking of how gender was read (or not read). Either scenario produced the same outcome.

“People look at you like you don’t exist in academia. They forget you have a torso,” she told me. It was even worse when she had her baby, ran into her supervisor, and he didn’t seem to see the baby she was now holding. As much as she didn’t want her sole identity to be a mother of two kids, and she wanted to make her way in academia, she still couldn’t fathom the large disconnect they were making. If people did acknowledge her pregnancy, they assumed it to be a mistake since she was relatively young and since something like that just didn’t happen in university. “It’s like they forget we have bodies,” she concluded and it was the part that resonated with me the most.

As much as I love ideas, books, art, and academia, we were discussing the one thing that discouraged us the most (to the point of us both thinking of dropping out under several instances). They forgot that we had a body, and sometimes needed special attention because of it, and in her case, that her body produced life that she still needed to look after. My friend Janette, another mother, has also talked about just how much time having kids takes up in a day and how no one even really mentions it. None of us wanted a free pass, but we wanted some type of acknowledgment. Without it, we felt completely fragmented.

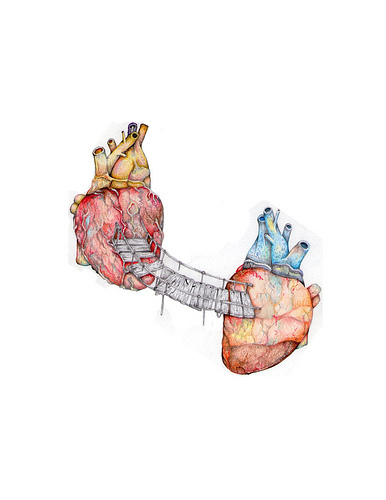

The idea of fragmentation is huge within this story. It is exactly what is happening to Bernard and Thomas and everyone who is around him. When he is losing his memory, everyone feels as if they are losing parts of themselves. This is the problem with memories - and ideas that then form our identities – they are ephemeral. They may go away and then we are left with just that body. The body itself is another hugely important thing for this story; Thomas makes mention of having the same body as Bernard several times, people talk to one another using body language, and even paint with their bodies. I wanted to focus on what had so often been ignored: that the body tells a story just as much as words do. Moreover, when you begin to lose those words, those ideas, and those memories, I wanted something to still be there. I wanted Jasmine’s pregnancy to be acknowledged as something linked with her body (and more will come with this later) and Thomas to feel incorporated somehow to the other people he interacted with through their bodies. I wanted there to be something left over when, in theory, Bernard began to “disappear.” He doesn’t disappear because he will always be there, taking up space. I wanted there to still be some type of communication between the two of them when words went away, and there is – touch. There is touch and sight and listening. There is still lots left of him. Basically, I wanted this story to remember what we all seemed to be forgetting, not just within academia, but within a lot of public spaces: we all have bodies. Though you can call them different things and turn them into identity politics, we all have a body. There is no getting around that, as much as we try.

The fragmentation of those ideas, and those identities, however, are still in a precarious mix in the story. The mother that I had been talking to that day about her pregnancy, her thesis project was on archiving an author’s work. Jasmine’s story at the beginning of this section on the professor dying of cancer was similar to this person’s experience. She had her whole project put on hold because of ethics issues and she had to deal with a lot of bullshit, aside from the daily fragmentation. She spent so much time archiving the work of Ivone Vera, an African writer who had died of AIDS suddenly, and I had spend so much time learning and studying about archives in my own classes that it gave me the idea. What if you could take all the pieces that seemingly have no meaning and string them up again to make a complete narrative again? What if you take something that is insignificant, like a flower or notes in the margin of a text, and you make it into something important again? This is what I felt that archiving did. This was what I wanted to do in my story so that when the body was leftover, and the ideas no longer made sense, there was a way to make sure that some cohesion was left by the end of it.

In my first graduate class, I did a project on Ann Cvetkovich’s book, An Archive of Feelings. She discusses how one could archive feelings, something that is ephemeral and intangible by definition, by using a solid object. Take a letter, and those memories attached to the letter are then persevered if the letter is preserved. It becomes an active way of remembering, and even if the original meaning is lost, there is still the object that can later be interpreted. She focused her own archive work on queer/lesbian subcultures, ones that periodically have their history either suppressed or erased completed. By developing archives and keeping them personalty run, it was a way to keep their history alive.

Bernard in the story is not as large as the underground subcultures of the 1970s and 80s, but he does have quite a huge network around him in the story. There are all these people, from Hilda to Callie and Dean and Marc and Thomas’ parents, who would not have any meaning in relation to one another without him being present. He is at the centre of this web. So when he starts to disappear, the only real way of finding any type of cohesion is to make an archive of him. Every single person he has known will contribute something, and Thomas sets out to do this.

It is just the beginning of this project, but even now, it is clear that it will never really be over. There are so many things to contribute, so many little stories to tell, and I don’t even mean within this narrative as a whole. One thing, particularly with Jasmine’s story about Bernard, that I wanted to emphasize with this story is that the reader is the most important part. Without the reader, there is no story. This is what the meaning of Tout ce qui n’est pas donne est perdu can translate into. All that is not given is lost – if someone doesn’t tell a story, it does not exist. If someone does not share an experience, it may as well never happened. If the second part of the equation is gone – so if Bernard is forgetting, it is imperative for Thomas, Jasmine, Vivian and everyone else involved to be recreate it. To tell it again to remember it.

This may seem convoluted and it may seem way too involved (I have told you all before and I will say it again: I am neurotic and spent way too much time working on this), but this website is an archive, too. It is a part of the idea of Bernard as anything else. The art section on here that people have contributed to, that is part of his legacy. I know he is just a fictional character. He is not really going away because he was never really ‘real’ to begin with, and all of that other stuff, but he is an idea. I can get away with at least that much, right? Bernard is an idea and though he is manifested in a person as a character in a book, that book will eventually end. I wanted that book to end a long time ago when I finished the first one and then left, hoping people would forget about it. But an idea is harder to kill. An idea never really goes away, and even if it does, an archive can kick start it again.

The next section of the book is the last section, aptly titled Last Words. It is impossible for Bernard to die in this, because you can’t really kill someone who was never alive to begin with. He has always been an idea, and he will always be one. Don’t worry about the end, because a story never really does end so long as you remember it. You may hate what I do with the next few pages, the next few chapters, or the book as a whole. But the idea of Bernard is still there. Make something new with him. Take this archive idea and create something for yourself. Don’t worry about the end, because like an archive, it will never really be over. Last Words is merely wishful thinking.

Evelyn Deshane's Blog

- Evelyn Deshane's profile

- 46 followers