Blog in Progress: Macaroni and Gravy

By Lisa Borders

Until this summer, I’d never seen an episode of The Sopranos. I had a huge resistance to watching the series, despite the fact that so many of my friends had told me how terrific, ground-breaking, well-written it was. Part of my resistance, I think now, was that during much of the time the show was on the air, I was writing a novel that was set in New Jersey. And while my rural South Jersey setting is an entirely different world from The Sopranos’ gritty North Jersey, on some level I probably didn’t want that vision of New Jersey competing with my own.

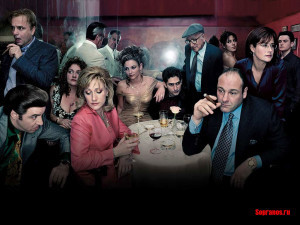

This summer, not long after the death of actor James Gandolfini, who played Tony Soprano, I decided to give the show a try. I was hooked from the first episode, and ran through all six-plus seasons in a frighteningly short span of time. The controversial final episode intrigued me so that I found myself googling analyses and theories; what I read made me want to go back and watch the pilot episode again. Soon, I found myself re-watching the entire series.

There are television shows I love and have watched over and over: various Star Trek franchises, Gilmore Girls, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Freaks and Geeks. In most cases it’s because I enjoy being in the world of the series, or identify with the characters. But it’s rare for me to rewatch a television series in the way I reread a novel I’ve loved, for craft. Yet that’s what I found myself doing with The Sopranos.

I certainly don’t like hanging out at the Bada Bing strip club the way I enjoy visiting the Gilmore Girls’ Stars Hollow, yet I find myself just as engrossed in The Sopranos on second viewing as I was the first time around. This is largely because so much is happening in The Sopranos from a dramaturgical standpoint that I’m catching things I missed on first viewing: symbolism, thematic connections, subtly ironic lines of dialogue.

The Sopranos, in fact, uses a surprising number of novelistic tools to tell its story – elements of craft that a feature-length screenplay, with its necessary compression, could never accommodate. I’d argue that the series has much more in common with a novel than it does with a screenplay, and that it has much to teach the novelist.

Here, then, is my list of the top five craft lessons The Sopranos can teach novelists. Please note that this list is rife with spoilers, for those of you who haven’t seen the series. (And if you haven’t, stop reading this post, start watching the show now, and return to the list in three months.)

1. Sometimes difficult narrative problems require ingenious, risky solutions. The Sopranos is not so much a story about the Mafia as a study of an antihero’s interior life, and his relationships with others. If series creator David Chase had been writing a novel, he might have chosen a first person or close third person point of view to convey Tony’s inner life. But there is no way to access a character’s direct thoughts in a work written for the screen, and this must have posed a huge dilemma for Chase: how could he possibly tell the viewer everything he, the writer, knew about Tony? Sometimes films use a voice-over narration technique to convey a character’s thoughts, but this often comes across as artificial and cheesy, and I’m glad Chase didn’t do that. Instead, he took a giant risk: he had Tony Soprano regularly see a psychiatrist. I can just imagine a disbelieving network executive at a pitch meeting: “This guy is the Mob boss of North Jersey, but he goes to see a shrink? No one will buy that!” And indeed, Chase’s device requires a huge suspension of disbelief on the viewer’s part. To render it more plausible, Chase gives Tony Soprano severe panic attacks that have caused him to pass out – in front of his business associates, in a world where showing weakness can be deadly. This becomes evident by the end of the pilot episode, and makes Soprano’s sessions with his shrink infinitely more believable.

2. Counterpointed characterization. The great Charles Baxter defines counterpointed characterization as what happens in a work of fiction when “certain kinds of people are pushed together, people who bring out a crucial response to each other.” There are many examples of counterpointed characterization in The Sopranos, but perhaps the best – and most extensive – is Tony’s relationship with his psychiatrist, Dr. Jennifer Melfi. It’s no accident that Dr. Melfi is a woman; a female shrink was vital to elicit some of the buried sides of Tony that I’m certain Chase wanted the viewer to see. As the series unfolds, Dr. Melfi is one of only two female characters in a position to challenge Tony’s antiquated views about women and about different races and cultures (the other is his college-educated daughter, Meadow). While Dr. Melfi challenges Tony, she also brings out aspects of his personality we might never be able to see otherwise; and because we see Dr. Melfi’s sessions with her own psychiatrist, we also see the other side of this counterpoint, elements of her character that treating Tony has brought out.

3. Shifts between scenes/chapters and the passage of time. Novelists often struggle with how to move from scene to scene or chapter to chapter, especially when a significant amount of time has elapsed between the two. The best way to handle this is often to just jump right in to the next scene, and work a clue or two within the action as to how much time has elapsed. Chase often uses this technique to great effect. At the end of Season 4, for example, Tony’s sister Janice and Bobby Baccalieri have started dating. In the first episode of the next season, Janice is at Bobby’s house preparing dinner. It quickly becomes clear that she and Bobby are hosting dinner for Tony and his children – and, when Janice says “This is my house, Tony” – that Janice and Bobby are now married. Chase doesn’t spell it out, but he does convey the passage of time while staying in scene and not over-explaining.

4. To know your beginning, you have to know your ending. When I teach a lesson in novel openings, I talk a lot about overall structure and the novel’s climax. Watching the series finale and then rewatching the pilot episode immediately afterward, I was struck by the extent to which the ending of The Sopranos addressed themes, tensions and characters introduced in the pilot. To accomplish this, series creator Chase must have had the entire story arc for all the seasons mapped out from the beginning, just as a novelist maps out chapters, once a first draft is complete and the revision process begins.

5. Great works of art should provide some resolution while also providing room for interpretation. The final season of The Sopranos unfolds like the end of a Shakespearean tragedy, as many brewing issues in this violent world come to a head. Tony’s son, A.J., who struggles with depression for much of the series (as does his father), attempts suicide. A simmering dispute with the New York mob erupts in the killings of several of Tony’s key men, and sends Tony into hiding.

In the final episode, the main threat from the New York gang has been killed, and Tony feels he has struck a deal with the remaining men. A.J. has a girlfriend and seems to be doing better; daughter Meadow becomes engaged; Tony and his wife Carmela, often at odds, seem to be in a good place. As Tony comes out of hiding and the family meets at a restaurant, it seems many of the main characters’ story lines have some resolution. And then … Chase seems to end the episode in mid-scene. The screen goes black as Tony looks up at the front door of the restaurant, where the viewer knows Meadow is about to walk in. The black screen is held for about ten seconds, with no music, no sound. Then the credits roll.

On first viewing, that last scene from the series finale reminded me of the ending of David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest in its apparent lack of resolution. I felt the cut in mid-scene underscored the ongoing nature of the danger Tony is in. Yes, he’s cheated death again, as he has many times before over the course of the series, but it doesn’t matter if he’s killed in this restaurant, on this night; he most likely will be killed eventually. It’s an implied ending, an ending the viewer must project.

But there’s another possible interpretation, one that I’m reluctantly coming around to believing: that Tony is killed at the moment he looks up at that door, that the screen goes black and silent because he has died. There are numerous shots from his point of view in this last scene of the series, and the final shot is from his point of view as well. An excellent explanation of this interpretation, walking the viewer through the final scene, can be found here.

What were Chase’s intentions for that final scene? It doesn’t matter. What matters is that he created an ending that resounds with all that came before, but leaves the viewer wanting to know more, interpreting and debating. As a novelist, it’s the kind of final scene I aspire to; and it’s a fitting ending for a series that is, in my opinion, a work of art.

Tweet