Canton: The European Reservation

Cross-posted from Unbound, where the Devil and the Hindmost needs your support to be published.

Working abroad was a very different prospect in the age of steam. Circumstances had vastly improved since the beginning of the century: steamships were much faster and more reliable than the packets that had relied on the fickle winds. The expanding telegraph network allowed communications to be measured in days rather than weeks. Yet the best recorded time between Southampton and Calcutta in 1856 was 37 days, and there was still no telegraph link between Canton and Hong Kong, which meant despatches had to travel the last mile by boat. For all the dramatic shrinking of the world that happened in the middle of the 19th century, it was still a very big world indeed.

Noah, the hero of the Devil and the Hindmost, is sent forth from England to make his fortune. The irony of his great adventure, and all those who went to work in the Far East at that time, was that his world-spanning journey ended with him confined to a space smaller than the Northern village where he grew up.

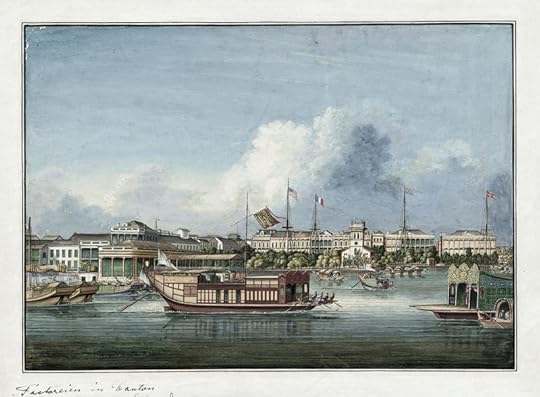

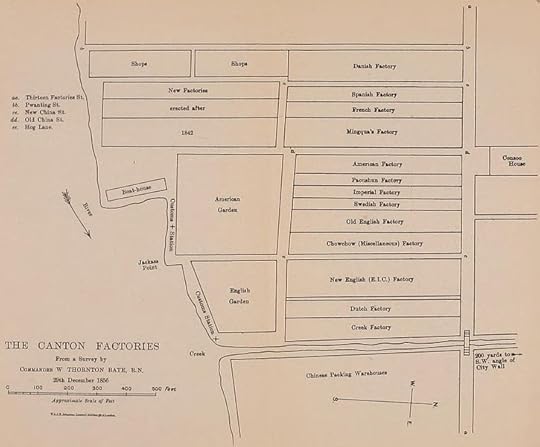

Imperial China had always sought to manage contact with Europe as one would an infectious disease. At the beginning of the 19th century, Westerners were permitted only on a thin strip of waterfront outside the walled city of Canton (actually Guangzhou, but the British preferred to use a Portuguese word rather than the Chinese name.) All trade was conducted through a guild of merchants, the Hong. Westerners were forbidden from going anywhere else in China, or even bringing their families with them to Canton.

The Europeans lived and worked in the thirteen factories, divided by nationality. The factories were more properly warehouses, two stories high on the waterfront, three in the rear. Inside, they were divided into contiguous apartments, storerooms, and offices. Merchants and their clerks slept on either hard rattan mats or mattresses filled with bamboo shavings. The bigger factories had billiard rooms and libraries, but beyond them and the two tiny gardens, diversion was in short supply. The foreign district was tiny – one resident estimated the whole sector as approximately 270 steps East to West, and even less North to South. Leaving this European reservation , or trying to enter Canton itself, was forbidden on pain of death.

The First Opium War changed this peculiar arrangement. The British seized Hong Kong, and other ports were opened by the treaty that ended the war. Yet when Noah arrives in 1856, the gates of Canton remained closed to Westerners, who were still confined to their factories and forbidden on pain of death from travelling inland. This threat by the Qin was not an idle one: missionaries regularly flouted it in their pursuit of souls, and were as regularly executed for the transgression. To work in the factories of Canton in 1856 was to be confined to an industrial estate on the other side of the world, surrounded by people whose language you could not understand.

It was no surprise then how much hostility there was around this little European nature preserve. Most of the businessmen and officials were there only for the money, felt themselves superior to every Chinese no matter their rank within their own society, and were anxious to leave as soon as possible. They regarded the closed gates of Canton as a personal affront from lesser beings. The Chinese, for their part, considered their English trading partners uncultured barbarians, arrogant and dangerous. This mutual contempt was kept in check by mutual greed for a time. But the British knew their strength, and when the Qin refused to open the country to further trade, Her Majesty’s servants decided to accomplish it by force.