Taps For John Crowder

Public monuments, at their best, call us to certain ideals that have been exemplified in the past and remain vital in the present. The individuals that they commemorate do matter, but matter less than the transcendent purpose for which they stand. There are thousands of monuments from America's Civil War, ranging from the generic to the stirring to the highly problematic, but each one stands for things that Americans value in their heroes and heroines, as well as in themselves.

If I had twenty grand or so lying around, I would commission a statue of John H. Crowder, and lobby for its placement in or near Port Hudson, Louisiana. It would fulfill that transcendent purpose. But I do not have twenty grand lying around, so Crowder will likely remain unheralded, while existing monuments continue to extoll the era's prominent generals and politicians.

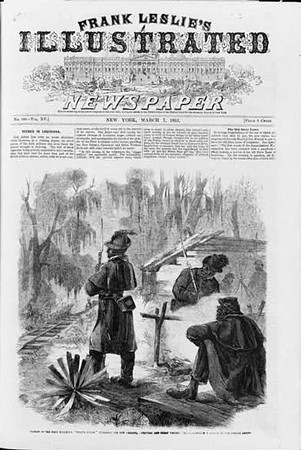

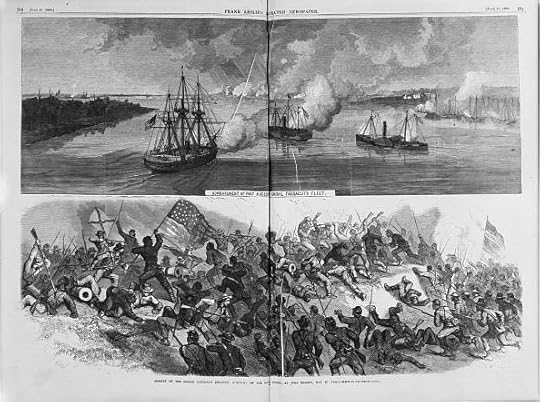

Union battery at Port Hudson, Louisiana, 1863. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

My first exposure to the subject of black troops in the Civil War occurred in the fifth grade, when at the Eleanor B. Kennelly School library (Hartford, CT) I discovered Worth Fighting For: A History Of The Negro In The United States During The Civil War And Reconstruction, by Agnes McCarthy and Lawrence Reddick. (Decades later, in my novel Lucifer's Drum, I gave the name Reddick to an African American platoon sergeant.) Central to the book was the assault on Fort Wagner, South Carolina, on July 18, 1863, by the Massachusetts 54th—an event later immortalized in the 1989 film Glory.

The Fort Wagner battle has been referred to as "obscure" but was actually well reported at the time, especially in newspapers with Abolitionist leanings. It had the dramatic essentials—a doomed yet valiant charge by disciplined black troops and, moreover, a dashing white commander killed in action. Colonel Robert Gould Shaw's last hour was surely his finest—smoking a cigar just before the charge, talking with calm affection to his men, personally leading the regiment as it headed through sheets of cannon fire toward the parapet, his death pretty much certain. If there is such a thing as a good death—and I suspect there is—no one ever died better. But Fort Wagner was not the first major use of black Union troops in battle, nor was the valor displayed there unequalled. Several weeks before, the Battle of Port Hudson—Lieutenant John Crowder's first and last action—had showcased the potential of African American soldiery. The one missing element, in terms of lasting public awareness, was a picturesque white martyr.

In the spring of 1863, only two Confederate strongholds remained on the Mississippi—Vicksburg and Port Hudson. While Grant besieged the former, Major-General Nathaniel P. Banks had the task of taking the latter. The previous December, Banks had replaced Major-General Benjamin F. Butler as head of the Army of the Gulf at New Orleans. Banks was a former governor of Massachusetts and a military mediocrity, having had his clock cleaned by Stonewall Jackson in the Shenandoah Valley. One of his failures there had been inadequate reconnaissance. At Port Hudson, he would repeat this lapse and many Union boys would pay for it.

The byzantine culture of New Orleans—a major center of the slave trade—featured a racial caste system based on skin tone as well as blood percentage. There was a large community of free blacks, some slave holders themselves, and a mixed-race elite. At the war's outset, some 1,100 free African Americans formed the Louisiana Native Guard to help defend New Orleans and demonstrate their worth as citizens. The Louisiana legislature, nervous at the spectacle of armed black men—with black officers, even—passed a law that disbanded the regiment. But then the governor, nervous before the Union military threat, defied the legislature and called the Guard back to duty. None of it mattered—New Orleans fell anyway in late April, 1862, when Union Admiral David Farragut's fleet came thundering in, and the Guard was again disbanded.

Yet in September, Butler organized a black Union regiment and gave it the same name. Some ten per cent of the men who had joined the Guard's Confederate incarnation now signed up for this Yankee one, their pride as Southerners eclipsed by an eagerness to combat white supremacy. Some of them took up their previous ranks as line officers, commanding recruits who were for the most part newly escaped slaves. In these pre-Emancipation days, Union policy discouraged such enlistment; yet it gave way to the press of numbers, great enough so that the 2nd, 3rd and eventually the 4th Louisiana Native Guard had to be formed in addition. (In June of '63, with the siege of Port Hudson in progress, they would be absorbed into a more recently formed black outfit called the the Corps d'Afrique—why does just about anything sound better in French?—which would later be absorbed into the United States Colored Troops, or USCT.)

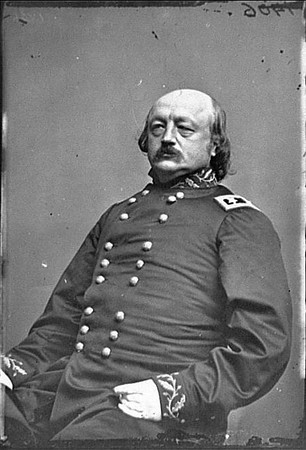

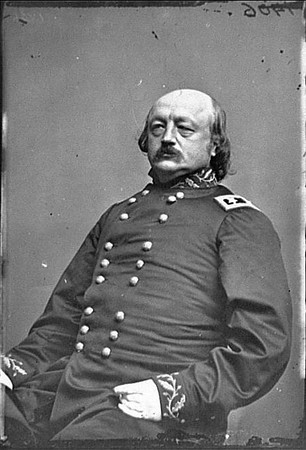

Union Major-General Benjamin F. Butler. Clever

and far-sighted, greedy and unscrupulous.

(Courtesy: Library of Congress)

And please pardon the following tangent.

It was an acerbic God indeed that arranged for Nathaniel Banks to replace Benjamin Butler. Butler, a Democrat and an appeaser of the pro-slavery forces, had narrowly lost to Banks in the race for governor of Massachusetts. In the war, however, he did far more than Banks—an avowed Abolitionist—to help escaped slaves. Commanding at Fortress Monroe, Virginia, in the war's first year, he cleverly declared such people "contrabands" as a legal way to deprive the Confederacy of labor. As military governor of New Orleans, Butler proved strict and effective, providing relief for the poor and taking strong measures to quash the annual yellow fever epidemic. But he became one of the most reviled men in the South following his infamous Order No. 28, which prescribed that any woman who insulted a federal soldier would be treated like a prostitute ("a woman of the town, plying her avocation.") "Beast Butler," they called him, using his likeness to decorate the bottom of chamber pots—"Spoons Butler," too, after he seized silverware from a lady trying to cross Union lines and arrested her as a smuggler. On top of this there were his shady financial dealings in partnership with his brother Andrew. The pair enriched themselves by buying confiscated cotton for cheap at rigged auctions, then selling it at a giant markup.

Thus, amid the rumble of controversy, Butler was recalled from New Orleans. Yet his feisty performance had made him a favorite among Radical Republicans—so President Lincoln found it politic to give him a new appointment in late '63, this time as commander for the Department of Virginia and North Carolina, based at Norfolk. There, his corruption really hit its stride. His deep involvement in the black market trade—across enemy lines, no less—was discovered near the war's end, and would have meant prison and disgrace for a less well-connected man. It was not malfeasance that caused his removal, however, but military ineptitude—he was no better on the battlefield than his rival Banks. In the blood-soaked spring of '64, his half-hearted offensive on the James River ended with his army stymied by a much smaller Confederate force. And in January, 1865, after his failure to capture Fort Fisher near Wilmington, North Carolina—the last major Atlantic port in the South's possession—overall commander General Ulysses S. Grant had him sacked.

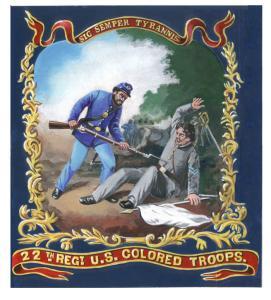

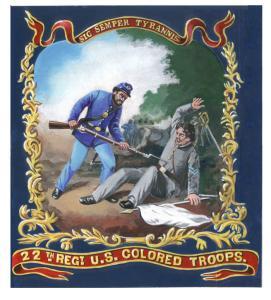

"Sic Semper Tyrannis." The 22nd Regiment

USCT, featured in Lucifer's Drum, had a pretty

no-nonsense battle flag. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

Butler went on to serve five terms as a Republican congressman and one, finally, as governor of Massachusetts (reverting to the Democrats—the man was nothing if not flexible.) Rising to prominence in the House, he skillfully managed the impeachment proceedings against President Andrew Johnson, which famously fell short by one vote. He was an able administrator, a brilliant attorney, a successful industrialist (cartridge manufacturer) and died very rich. He embodied much of what we decry and lampoon in politicians. Still, he was something more than a venal scoundrel and lowdown profiteer, and that's what makes him interesting. In cases that didn't trigger his avarice, he showed nerve and far-sightedness.

Having shed his early role as a slavery accommodationist, and having pioneered black recruitment at New Orleans, he became a sincere believer in African American fighting mettle. He later commanded units of the United States Colored Troops in Virginia, where several (including the 22nd USCT, which has a part in Lucifer's Drum) proved instrumental in the victory at Chaffin's Farm or New Market Heights, Sept. 29-30, 1864, charging through intense fire to turn the Confederate left. Twenty-three USCT troops were awarded the Medal of Honor as a result, and Butler had another medal struck—the so-called Butler Medal—for an additional 200 men. In Congress, he was a key promotor of the Civil Rights Bills of 1871 and 1875, the first one authorizing strong measures against the Ku Klux Klan and the second forbidding racial discrimination in public accommodations (later declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court and not redeemed until the Civil Rights Act of 1964.) He supported greenback currency, an eight-hour work day and women's suffrage. As Massachusetts governor, he appointed the nation's first African American judge as well as its first Irish Catholic judge. He named the great Clara Barton to head the Massachusetts Reformatory for Women, the state's first-ever instance of a female in an executive position. On the Greenback/Anti-Monopoly ticket, Butler ran for President in 1884 but didn't get a single electoral vote.

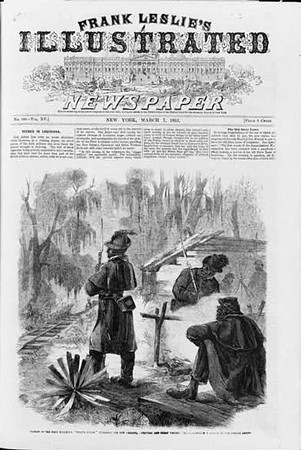

Magazine illustration of Native Guardsman on

picket duty. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

But back to the Native Guard . . . As soon as Nathaniel Banks took command in New Orleans, he set out to purge the Guard regiments of its black line officers and replace them with white ones. Abolitionist or no, he made the typical race-based assumption that these men were sub-standard. But while the 2nd and 3rd Regiments were brought fully under white command, the 1st resisted the order and retained its black officers. These included two who were, each in his own way, extraordinary: Captain Andre Cailloux and 2nd Lieutenant John H. Crowder.

Born a slave of mixed race, Cailloux had petitioned for his freedom at age 21 and been granted it. He founded a successful cigar-making business and married a woman of similar background named Felicie Coulon. They had four children, three of whom lived. On the side, Cailloux was also a feared amateur boxer. Literate in French as well as English, he helped support the Institute Catholique, which had a leading role in educating the city's free and orphaned black children. At the war's outbreak he was 36 and a respected leader in the large African-French (Creole) community. He was among those who first signed up for the Native Guard's Confederate version, proud to defend the city he loved, but put on the blue uniform when his chance came. His Company E was notably well drilled.

Not even a staff this big could save Union Major-General Nathaniel P. Banks (seated

center) from mediocrity. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

John Crowder had been born to a free black couple in Louisville, Kentucky. He was still an infant when his father left as an army hireling for the Mexican American War and did not return. His mother took John with her to New Orleans, where she had friends and found work as a seamstress. She also married a steamboat steward who proved a worthless drunk and eventually abandoned her and his stepson. From the age of eight, John worked—as a cabin boy, as a steamboat steward, as a jeweler's porter—always forwarding his pay to his mother, Martha Ann. A prominent black minister took an interest in him and saw to his education.

We can only infer how impressive Crowder was by the fact that he became an officer while managing to conceal his age—which was 16. A handful of his letters exist in the special collections library at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, most of them written to his mother. In one he remarked to her, "If Abraham Lincoln knew that a colored Lad of my age could command a company, what would he say?" Crowder's youth brought consternation within the ranks, however, especially since he outshone other officers in leadership qualities. So besides regular insults from white citizenry, he had to contend with them from fellow officers. One in particular, a jealous captain later prosecuted for cowardice, started spreading false rumors about Crowder's personal conduct. When one of this captain's men committed a lewd act in front of an older woman—a friend of Crowder's who had nursed him through a fever—the young lieutenant reported it, his nemesis having failed to do so. "I remember your first lesson," he wrote his mother, "that was to respect all females." After this, the slander campaign against him intensified. But he was resolved not to be driven from the Native Guard—"to stay in the service, as long as there is a straw to hold to."

The Guard had been used only for fatigue duty—chopping wood, digging earthworks, guarding rail lines. Then, in May 1863, the greater part of it was sent to lay bridges around the Confederate bastion at Port Hudson. Having encircled the town, General Banks launched an attack from the east on the morning of the 27th, probing for weak spots in the enemy defenses. When it stalled, the 1st and 3rd Native Guard were sent in from the north, crossing a pontoon bridge over Foster's Creek and heading down Telegraph Road toward Port Hudson. Incredibly, no one from Banks on down had ordered the terrain scouted. Had they done so, they would have found that the enemy had made maximum use of it, placing riflemen atop a bluff on the left, alongside the road. Underbrush, felled trees and a man-made backwater (channeled from the Mississippi) made the position practically impregnable. On the right, the flooded Mississippi formed a large natural backwater full of trees, while down the road stood another bluff holding the main Confederate works.

There were only two Union cannon, and these were quickly disabled by Confederate artillery. The Guard shifted to the left and formed two lines, the 1st Regiment and then the 3rd, moving out of the woods and into a relatively open area. They never had a prayer. Still they charged, taking enfilading fire from the roadside bluff and raked by canister in front. Torn up, the 1st stalled within two hundred yards of the enemy position, whereupon the 3rd barreled past them and were in turn torn up. Twice they fell back and re-formed and twice again they charged. Some troops tried to get at the enemy by wading through the riverside backwater or climbing the roadside bluff, but it was in vain. The Guard withdrew, having lost about 200 out of 1,000. The Confederates recorded not one casualty.

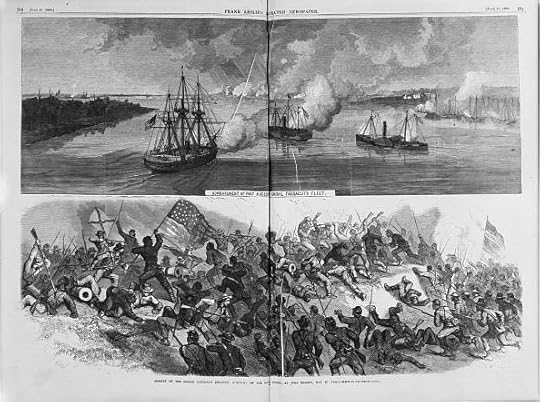

Bottom magazine illustration shows the Native Guard assault at Port Hudson

(May 27, 1863). The dim figure on the far right with sword raised is supposedly Captain

Andre Cailloux. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

Fatally wounded, John Crowder had been taken to the rear, where he died that afternoon. Andre Cailloux survived nearly to the battle's end, leading his company and bawling orders in both French and English, though a rifle ball had shattered his forearm. Finally a shell killed him. In subsequent days, Rebel sharpshooters prevented the collection of the dead, so Cailloux's noble corpse moldered on the field. When it was at last recovered, he received a hero's funeral attended by thousands in New Orleans. Crowder's mother had to bury her son in a pauper's grave. At Port Hudson, meanwhile, Banks launched a second infantry assault on June 14. It was a costly, ill-coordinated failure, made worse by fog. From there it settled into a siege with frequent bombardments, while Confederate Major-General Franklin Gardner conducted a stubborn and intelligent defense. Disease, desertion, starvation and an ammunition shortage finally led the Southern garrison to surrender on July 9, though only after news came of Vicksburg's fall five days earlier.

The Guard's performance changed a lot of minds concerning black troops. Union Captain Robert F. Wilkinson wrote, " . . . the black troops at P. Hudson fought & acted superbly. The theory of negro inefficiency is . . . at last exploded by the facts." General Banks stated, "The severe test to which they were subjected, and the determined manner in which they encountered the enemy, leaves upon my mind no doubt of their ultimate success." Banks' shortcomings had of course made that test more severe than it need have been. In any case, the protracted misery of Port Hudson left him in a poor light and permanently damaged his larger aspirations. We would never have a President Banks. (Like his adversary Butler and so many other forgotten politicians, he did indulge that fantasy for a spell.)

In faraway New York, the Times editorialized: "Those black soldiers had never before been in any severe engagement. They were comparatively raw troops, and yet were subjected to the most awful ordeal than even veterans ever have to experience—the charging upon fortifications through the crash of belching batteries. The men, white or black, who will not flinch from that will flinch from nothing. It is no longer possible to doubt the bravery and steadiness of the colored race, when rightly led."

"When rightly led." The knife-twisting irony here was, of course, that they acted courageously despite very poor leadership from the top. Even so, African American troops would have to prove themselves over and over—at Milliken's Bend, at Fort Wagner, at Ocean Pond, at Jenkins' Ferry, at Wilson's Wharf, at Brice's Crossroads, at Baylor's Farm and at Chaffin's Farm. Given the majority's tendency toward selective amnesia, they would in fact have to prove themselves in each war thereafter, well into the 20th Century. Race-based ideology has its self-protective reflexes, like any organism. When punched in the face, it takes a fallback position from which it can still resist full equality—a position like "When rightly led." Thus, in every similar instance, this qualifier would come droning up like a persistent wasp, with its own implicit qualifier: "by white officers." Only after President Truman's desegregation of the armed forces in 1948 would that wasp be finally swatted to a paste.

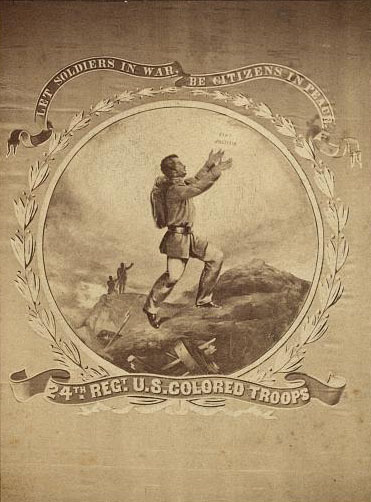

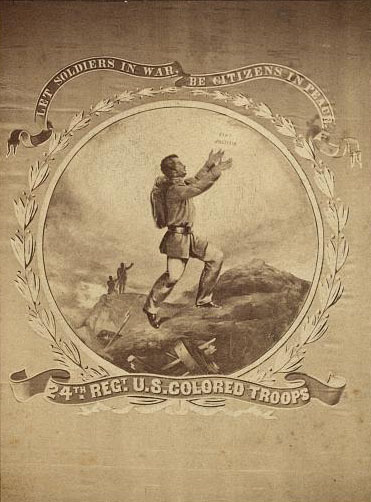

Regimental flag for the 24th USCT: Let soldiers in war,

be citizens in peace. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

Which brings me once and for all back to John Crowder—his mother's shining hope, dead at 17, buried anonymously. Andre Cailloux got to marry a woman he loved and have children, attain worthy goals and demonstrate character, gain standing in his community and accolades in death. In his last moments—surrounded by friends, I can only wish—John Crowder must have known what millions of dying boys in hundreds of wars have known: that despite all his yearning, he would never have these things. He exhibited just about every quality that makes youth beautiful in our sight—the supple mind, the ardent will, the high hopes, the unbounded bravery, the vivid personality, the generous humor, the aching promise. And the idealism—an idealism that would have been sorely tested, had he lived to a natural old age. Because he would have lived to see the rise of the Klan and the entrenchment of Jim Crow, the Nadir of the 1890's and the plague of lynchings, the use of sharecropping and the penal system to erect a de facto new slavery, the theft or destruction of hard-won property, the denial of education and the trampling of aspirations, the despoiling of those principles that America supposedly holds dear.

Whatever he would have done or said or become in response, we will never know. And I guess that is the precise reason we should treasure him—a youth forever suspended in hope, aching with promise. I swear there are nights when I can feel his ghost moving among us, watching it all. That's why any monument to John Crowder would be to the person he was, the man he would have become and the ideals he signed up for, but also to grief and loss. The worst kind of grief and loss imaginable.

Final tidbits: Future politician, publisher and civil rights pioneer Pinckney Benton Stewart Pinchbeck, a free black man, was a company commander with the 2nd Louisiana Native Guard but resigned his commission after twice being passed over for promotion and repeatedly insulted by white officers. During Reconstruction, he was elected lieutenant-governor of Louisiana and served as governor for 15 days after the sitting governor stepped aside to face impeachment charges. Pinchbeck was later elected to the U.S. Congress and then the Senate, though he was blocked from taking his seat. Each of these attainments was a first for a black politician.

Also: Jamaican-born and of mixed race, Morris W. Morris served in the Confederate version of the Native Guard and briefly in the Union one, as a 19-year-old lieutenant. He was the only black Jewish man to serve on either side. Re-naming himself Lewis Morrison, he went on to become a famous actor. He was the grandfather of Hollywood's Bennett sisters—Constance, Barbara and Joan—and the great-grandfather of TV shock-show host Morton Downey, Jr.

Here is a video link: U.S. Poet Laureate Natasha Trethewey reading her magnificent poem "Elegy For The Native Guards" on Ship Island, MS, where the 2nd Louisiana Native Guard did garrison duty: http://southernspaces.org/2005/elegy-...

{Note: Much of my information here came from Joseph T. Glatthaar's cornerstone work Forged In Battle: The Civil War Alliance Of Black Soldiers And White Officers, which also informed the historical background for Lucifer's Drum.}

If I had twenty grand or so lying around, I would commission a statue of John H. Crowder, and lobby for its placement in or near Port Hudson, Louisiana. It would fulfill that transcendent purpose. But I do not have twenty grand lying around, so Crowder will likely remain unheralded, while existing monuments continue to extoll the era's prominent generals and politicians.

Union battery at Port Hudson, Louisiana, 1863. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

My first exposure to the subject of black troops in the Civil War occurred in the fifth grade, when at the Eleanor B. Kennelly School library (Hartford, CT) I discovered Worth Fighting For: A History Of The Negro In The United States During The Civil War And Reconstruction, by Agnes McCarthy and Lawrence Reddick. (Decades later, in my novel Lucifer's Drum, I gave the name Reddick to an African American platoon sergeant.) Central to the book was the assault on Fort Wagner, South Carolina, on July 18, 1863, by the Massachusetts 54th—an event later immortalized in the 1989 film Glory.

The Fort Wagner battle has been referred to as "obscure" but was actually well reported at the time, especially in newspapers with Abolitionist leanings. It had the dramatic essentials—a doomed yet valiant charge by disciplined black troops and, moreover, a dashing white commander killed in action. Colonel Robert Gould Shaw's last hour was surely his finest—smoking a cigar just before the charge, talking with calm affection to his men, personally leading the regiment as it headed through sheets of cannon fire toward the parapet, his death pretty much certain. If there is such a thing as a good death—and I suspect there is—no one ever died better. But Fort Wagner was not the first major use of black Union troops in battle, nor was the valor displayed there unequalled. Several weeks before, the Battle of Port Hudson—Lieutenant John Crowder's first and last action—had showcased the potential of African American soldiery. The one missing element, in terms of lasting public awareness, was a picturesque white martyr.

In the spring of 1863, only two Confederate strongholds remained on the Mississippi—Vicksburg and Port Hudson. While Grant besieged the former, Major-General Nathaniel P. Banks had the task of taking the latter. The previous December, Banks had replaced Major-General Benjamin F. Butler as head of the Army of the Gulf at New Orleans. Banks was a former governor of Massachusetts and a military mediocrity, having had his clock cleaned by Stonewall Jackson in the Shenandoah Valley. One of his failures there had been inadequate reconnaissance. At Port Hudson, he would repeat this lapse and many Union boys would pay for it.

The byzantine culture of New Orleans—a major center of the slave trade—featured a racial caste system based on skin tone as well as blood percentage. There was a large community of free blacks, some slave holders themselves, and a mixed-race elite. At the war's outset, some 1,100 free African Americans formed the Louisiana Native Guard to help defend New Orleans and demonstrate their worth as citizens. The Louisiana legislature, nervous at the spectacle of armed black men—with black officers, even—passed a law that disbanded the regiment. But then the governor, nervous before the Union military threat, defied the legislature and called the Guard back to duty. None of it mattered—New Orleans fell anyway in late April, 1862, when Union Admiral David Farragut's fleet came thundering in, and the Guard was again disbanded.

Yet in September, Butler organized a black Union regiment and gave it the same name. Some ten per cent of the men who had joined the Guard's Confederate incarnation now signed up for this Yankee one, their pride as Southerners eclipsed by an eagerness to combat white supremacy. Some of them took up their previous ranks as line officers, commanding recruits who were for the most part newly escaped slaves. In these pre-Emancipation days, Union policy discouraged such enlistment; yet it gave way to the press of numbers, great enough so that the 2nd, 3rd and eventually the 4th Louisiana Native Guard had to be formed in addition. (In June of '63, with the siege of Port Hudson in progress, they would be absorbed into a more recently formed black outfit called the the Corps d'Afrique—why does just about anything sound better in French?—which would later be absorbed into the United States Colored Troops, or USCT.)

Union Major-General Benjamin F. Butler. Clever

and far-sighted, greedy and unscrupulous.

(Courtesy: Library of Congress)

And please pardon the following tangent.

It was an acerbic God indeed that arranged for Nathaniel Banks to replace Benjamin Butler. Butler, a Democrat and an appeaser of the pro-slavery forces, had narrowly lost to Banks in the race for governor of Massachusetts. In the war, however, he did far more than Banks—an avowed Abolitionist—to help escaped slaves. Commanding at Fortress Monroe, Virginia, in the war's first year, he cleverly declared such people "contrabands" as a legal way to deprive the Confederacy of labor. As military governor of New Orleans, Butler proved strict and effective, providing relief for the poor and taking strong measures to quash the annual yellow fever epidemic. But he became one of the most reviled men in the South following his infamous Order No. 28, which prescribed that any woman who insulted a federal soldier would be treated like a prostitute ("a woman of the town, plying her avocation.") "Beast Butler," they called him, using his likeness to decorate the bottom of chamber pots—"Spoons Butler," too, after he seized silverware from a lady trying to cross Union lines and arrested her as a smuggler. On top of this there were his shady financial dealings in partnership with his brother Andrew. The pair enriched themselves by buying confiscated cotton for cheap at rigged auctions, then selling it at a giant markup.

Thus, amid the rumble of controversy, Butler was recalled from New Orleans. Yet his feisty performance had made him a favorite among Radical Republicans—so President Lincoln found it politic to give him a new appointment in late '63, this time as commander for the Department of Virginia and North Carolina, based at Norfolk. There, his corruption really hit its stride. His deep involvement in the black market trade—across enemy lines, no less—was discovered near the war's end, and would have meant prison and disgrace for a less well-connected man. It was not malfeasance that caused his removal, however, but military ineptitude—he was no better on the battlefield than his rival Banks. In the blood-soaked spring of '64, his half-hearted offensive on the James River ended with his army stymied by a much smaller Confederate force. And in January, 1865, after his failure to capture Fort Fisher near Wilmington, North Carolina—the last major Atlantic port in the South's possession—overall commander General Ulysses S. Grant had him sacked.

"Sic Semper Tyrannis." The 22nd Regiment

USCT, featured in Lucifer's Drum, had a pretty

no-nonsense battle flag. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

Butler went on to serve five terms as a Republican congressman and one, finally, as governor of Massachusetts (reverting to the Democrats—the man was nothing if not flexible.) Rising to prominence in the House, he skillfully managed the impeachment proceedings against President Andrew Johnson, which famously fell short by one vote. He was an able administrator, a brilliant attorney, a successful industrialist (cartridge manufacturer) and died very rich. He embodied much of what we decry and lampoon in politicians. Still, he was something more than a venal scoundrel and lowdown profiteer, and that's what makes him interesting. In cases that didn't trigger his avarice, he showed nerve and far-sightedness.

Having shed his early role as a slavery accommodationist, and having pioneered black recruitment at New Orleans, he became a sincere believer in African American fighting mettle. He later commanded units of the United States Colored Troops in Virginia, where several (including the 22nd USCT, which has a part in Lucifer's Drum) proved instrumental in the victory at Chaffin's Farm or New Market Heights, Sept. 29-30, 1864, charging through intense fire to turn the Confederate left. Twenty-three USCT troops were awarded the Medal of Honor as a result, and Butler had another medal struck—the so-called Butler Medal—for an additional 200 men. In Congress, he was a key promotor of the Civil Rights Bills of 1871 and 1875, the first one authorizing strong measures against the Ku Klux Klan and the second forbidding racial discrimination in public accommodations (later declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court and not redeemed until the Civil Rights Act of 1964.) He supported greenback currency, an eight-hour work day and women's suffrage. As Massachusetts governor, he appointed the nation's first African American judge as well as its first Irish Catholic judge. He named the great Clara Barton to head the Massachusetts Reformatory for Women, the state's first-ever instance of a female in an executive position. On the Greenback/Anti-Monopoly ticket, Butler ran for President in 1884 but didn't get a single electoral vote.

Magazine illustration of Native Guardsman on

picket duty. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

But back to the Native Guard . . . As soon as Nathaniel Banks took command in New Orleans, he set out to purge the Guard regiments of its black line officers and replace them with white ones. Abolitionist or no, he made the typical race-based assumption that these men were sub-standard. But while the 2nd and 3rd Regiments were brought fully under white command, the 1st resisted the order and retained its black officers. These included two who were, each in his own way, extraordinary: Captain Andre Cailloux and 2nd Lieutenant John H. Crowder.

Born a slave of mixed race, Cailloux had petitioned for his freedom at age 21 and been granted it. He founded a successful cigar-making business and married a woman of similar background named Felicie Coulon. They had four children, three of whom lived. On the side, Cailloux was also a feared amateur boxer. Literate in French as well as English, he helped support the Institute Catholique, which had a leading role in educating the city's free and orphaned black children. At the war's outbreak he was 36 and a respected leader in the large African-French (Creole) community. He was among those who first signed up for the Native Guard's Confederate version, proud to defend the city he loved, but put on the blue uniform when his chance came. His Company E was notably well drilled.

Not even a staff this big could save Union Major-General Nathaniel P. Banks (seated

center) from mediocrity. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

John Crowder had been born to a free black couple in Louisville, Kentucky. He was still an infant when his father left as an army hireling for the Mexican American War and did not return. His mother took John with her to New Orleans, where she had friends and found work as a seamstress. She also married a steamboat steward who proved a worthless drunk and eventually abandoned her and his stepson. From the age of eight, John worked—as a cabin boy, as a steamboat steward, as a jeweler's porter—always forwarding his pay to his mother, Martha Ann. A prominent black minister took an interest in him and saw to his education.

We can only infer how impressive Crowder was by the fact that he became an officer while managing to conceal his age—which was 16. A handful of his letters exist in the special collections library at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, most of them written to his mother. In one he remarked to her, "If Abraham Lincoln knew that a colored Lad of my age could command a company, what would he say?" Crowder's youth brought consternation within the ranks, however, especially since he outshone other officers in leadership qualities. So besides regular insults from white citizenry, he had to contend with them from fellow officers. One in particular, a jealous captain later prosecuted for cowardice, started spreading false rumors about Crowder's personal conduct. When one of this captain's men committed a lewd act in front of an older woman—a friend of Crowder's who had nursed him through a fever—the young lieutenant reported it, his nemesis having failed to do so. "I remember your first lesson," he wrote his mother, "that was to respect all females." After this, the slander campaign against him intensified. But he was resolved not to be driven from the Native Guard—"to stay in the service, as long as there is a straw to hold to."

The Guard had been used only for fatigue duty—chopping wood, digging earthworks, guarding rail lines. Then, in May 1863, the greater part of it was sent to lay bridges around the Confederate bastion at Port Hudson. Having encircled the town, General Banks launched an attack from the east on the morning of the 27th, probing for weak spots in the enemy defenses. When it stalled, the 1st and 3rd Native Guard were sent in from the north, crossing a pontoon bridge over Foster's Creek and heading down Telegraph Road toward Port Hudson. Incredibly, no one from Banks on down had ordered the terrain scouted. Had they done so, they would have found that the enemy had made maximum use of it, placing riflemen atop a bluff on the left, alongside the road. Underbrush, felled trees and a man-made backwater (channeled from the Mississippi) made the position practically impregnable. On the right, the flooded Mississippi formed a large natural backwater full of trees, while down the road stood another bluff holding the main Confederate works.

There were only two Union cannon, and these were quickly disabled by Confederate artillery. The Guard shifted to the left and formed two lines, the 1st Regiment and then the 3rd, moving out of the woods and into a relatively open area. They never had a prayer. Still they charged, taking enfilading fire from the roadside bluff and raked by canister in front. Torn up, the 1st stalled within two hundred yards of the enemy position, whereupon the 3rd barreled past them and were in turn torn up. Twice they fell back and re-formed and twice again they charged. Some troops tried to get at the enemy by wading through the riverside backwater or climbing the roadside bluff, but it was in vain. The Guard withdrew, having lost about 200 out of 1,000. The Confederates recorded not one casualty.

Bottom magazine illustration shows the Native Guard assault at Port Hudson

(May 27, 1863). The dim figure on the far right with sword raised is supposedly Captain

Andre Cailloux. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

Fatally wounded, John Crowder had been taken to the rear, where he died that afternoon. Andre Cailloux survived nearly to the battle's end, leading his company and bawling orders in both French and English, though a rifle ball had shattered his forearm. Finally a shell killed him. In subsequent days, Rebel sharpshooters prevented the collection of the dead, so Cailloux's noble corpse moldered on the field. When it was at last recovered, he received a hero's funeral attended by thousands in New Orleans. Crowder's mother had to bury her son in a pauper's grave. At Port Hudson, meanwhile, Banks launched a second infantry assault on June 14. It was a costly, ill-coordinated failure, made worse by fog. From there it settled into a siege with frequent bombardments, while Confederate Major-General Franklin Gardner conducted a stubborn and intelligent defense. Disease, desertion, starvation and an ammunition shortage finally led the Southern garrison to surrender on July 9, though only after news came of Vicksburg's fall five days earlier.

The Guard's performance changed a lot of minds concerning black troops. Union Captain Robert F. Wilkinson wrote, " . . . the black troops at P. Hudson fought & acted superbly. The theory of negro inefficiency is . . . at last exploded by the facts." General Banks stated, "The severe test to which they were subjected, and the determined manner in which they encountered the enemy, leaves upon my mind no doubt of their ultimate success." Banks' shortcomings had of course made that test more severe than it need have been. In any case, the protracted misery of Port Hudson left him in a poor light and permanently damaged his larger aspirations. We would never have a President Banks. (Like his adversary Butler and so many other forgotten politicians, he did indulge that fantasy for a spell.)

In faraway New York, the Times editorialized: "Those black soldiers had never before been in any severe engagement. They were comparatively raw troops, and yet were subjected to the most awful ordeal than even veterans ever have to experience—the charging upon fortifications through the crash of belching batteries. The men, white or black, who will not flinch from that will flinch from nothing. It is no longer possible to doubt the bravery and steadiness of the colored race, when rightly led."

"When rightly led." The knife-twisting irony here was, of course, that they acted courageously despite very poor leadership from the top. Even so, African American troops would have to prove themselves over and over—at Milliken's Bend, at Fort Wagner, at Ocean Pond, at Jenkins' Ferry, at Wilson's Wharf, at Brice's Crossroads, at Baylor's Farm and at Chaffin's Farm. Given the majority's tendency toward selective amnesia, they would in fact have to prove themselves in each war thereafter, well into the 20th Century. Race-based ideology has its self-protective reflexes, like any organism. When punched in the face, it takes a fallback position from which it can still resist full equality—a position like "When rightly led." Thus, in every similar instance, this qualifier would come droning up like a persistent wasp, with its own implicit qualifier: "by white officers." Only after President Truman's desegregation of the armed forces in 1948 would that wasp be finally swatted to a paste.

Regimental flag for the 24th USCT: Let soldiers in war,

be citizens in peace. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

Which brings me once and for all back to John Crowder—his mother's shining hope, dead at 17, buried anonymously. Andre Cailloux got to marry a woman he loved and have children, attain worthy goals and demonstrate character, gain standing in his community and accolades in death. In his last moments—surrounded by friends, I can only wish—John Crowder must have known what millions of dying boys in hundreds of wars have known: that despite all his yearning, he would never have these things. He exhibited just about every quality that makes youth beautiful in our sight—the supple mind, the ardent will, the high hopes, the unbounded bravery, the vivid personality, the generous humor, the aching promise. And the idealism—an idealism that would have been sorely tested, had he lived to a natural old age. Because he would have lived to see the rise of the Klan and the entrenchment of Jim Crow, the Nadir of the 1890's and the plague of lynchings, the use of sharecropping and the penal system to erect a de facto new slavery, the theft or destruction of hard-won property, the denial of education and the trampling of aspirations, the despoiling of those principles that America supposedly holds dear.

Whatever he would have done or said or become in response, we will never know. And I guess that is the precise reason we should treasure him—a youth forever suspended in hope, aching with promise. I swear there are nights when I can feel his ghost moving among us, watching it all. That's why any monument to John Crowder would be to the person he was, the man he would have become and the ideals he signed up for, but also to grief and loss. The worst kind of grief and loss imaginable.

Final tidbits: Future politician, publisher and civil rights pioneer Pinckney Benton Stewart Pinchbeck, a free black man, was a company commander with the 2nd Louisiana Native Guard but resigned his commission after twice being passed over for promotion and repeatedly insulted by white officers. During Reconstruction, he was elected lieutenant-governor of Louisiana and served as governor for 15 days after the sitting governor stepped aside to face impeachment charges. Pinchbeck was later elected to the U.S. Congress and then the Senate, though he was blocked from taking his seat. Each of these attainments was a first for a black politician.

Also: Jamaican-born and of mixed race, Morris W. Morris served in the Confederate version of the Native Guard and briefly in the Union one, as a 19-year-old lieutenant. He was the only black Jewish man to serve on either side. Re-naming himself Lewis Morrison, he went on to become a famous actor. He was the grandfather of Hollywood's Bennett sisters—Constance, Barbara and Joan—and the great-grandfather of TV shock-show host Morton Downey, Jr.

Here is a video link: U.S. Poet Laureate Natasha Trethewey reading her magnificent poem "Elegy For The Native Guards" on Ship Island, MS, where the 2nd Louisiana Native Guard did garrison duty: http://southernspaces.org/2005/elegy-...

{Note: Much of my information here came from Joseph T. Glatthaar's cornerstone work Forged In Battle: The Civil War Alliance Of Black Soldiers And White Officers, which also informed the historical background for Lucifer's Drum.}

Published on November 20, 2015 01:07

•

Tags:

andre-cailloux, benjamin-butler, bernie-mackinnon, civil-war, corps-d-afrique, john-crowder, louisiana-native-guards, lucifer-s-drum, nathaniel-banks, new-orleans, port-hudson, united-states-colored-troops

No comments have been added yet.