Fernando Gros's Blog

October 14, 2025

The Case For Physical Media

The architect wanted to show me a house he had built. It had some ideas similar to some he had suggested for the mountain lodge I was wanting him to design. I walked in ready to look at kitchen and bathroom features. But what captured my attention was the vast lounge room.

Every wall was filled with expansive floor-to-ceiling bookcases. They were stacked with old books. Mostly novels and poetry and history. And vinyl. Lots and lots of vinyl. “Yes, he collects,” the architect said. But this felt less like a personal collection than some kind of treasure trove. A mirror held up to 20th-century Japanese culture.

There were a couple of sofas, a few more reading chairs, some side and coffee tables, a floor lamp, and a big dining table. But those vast bookcases and the high raked ceiling made this feel like more than just a living room. This was a place in which to live, in the fullest sense of the word. In which to flourish. A space that rewarded reading and listening patiently.

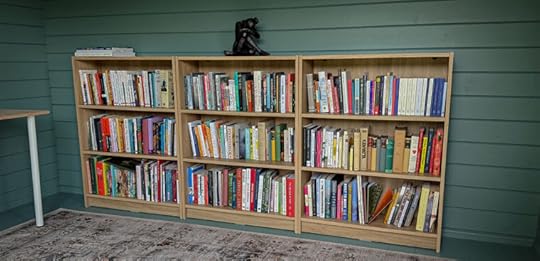

I still buy books. Physical books. Maybe too many books. Over the years I’ve had people look at my bookcases and ask, “Have you read all those books?” That really isn’t the point. You buy books in order to always have something to read. Not as tokens of having already read.

I also buy vinyl. And occasionally CDs, when vinyl isn’t an option. Lately, I’ve started buying DVDs and Blu-rays again.

This isn’t some kind of anti-streaming stance. I like Apple Music and Apple Music Classical. There are aspects of streaming for TV and film that I enjoy. Convenience and portability are things I appreciate.

But I wonder how sustainable these digital services are.

Streaming is costly. And the prices for these streaming services rise in ways untethered from how our income increases. Will they even be affordable in the future? Will they still stream the things we want? How many different services will we need to sign up for? And how useable will they be?

My father had to “upgrade” his cable service box recently. For his age, he’s very good with technology. To watch him struggle with a poorly designed menu system was painful. And there doesn’t appear to be any way to make the interface easier to navigate. There are no accessibility settings. The whole thing is actively hostile to any user who has less than perfect vision or lacks sharp reflexes.

I imagine myself in my 80s or 90s. I like to think I’d still want to watch the best new films. But I probably wouldn’t care much if I saw them months after they came out. What’s the rush? I’d love to still be reading every day. But I’ll probably be on fewer flights, or waiting less often in distant places, and so I might not need a library in my pocket like digital devices promise to be.

I’m not quitting digital streaming services. At least not now. Maybe I never will. But I’ve decided not to go all in on them either. I’m relying on them less and less. And enjoying the freedom that comes with that. I like that I can read a book, listen to music, or watch a film without worrying about what my password is or whether my payment details are up to date.

I also love that some Silicon Valley company can’t take away my access to the physical media I have on my shelves. Or edit their content to suit current political trends in a country I don’t even live in.

The life of the mind is an expression of freedom I want to hold onto.

From time to time, I think about that house with the vast bookcases. Sometimes I drive past it when I’m back in the Japanese Alps. I like to reconnect with the sense of awe I felt the first time I saw that lounge room. It was a vision of an ideal way to live. Made real in physical form. As I get older, it’s an increasingly appealing vision.

The post The Case For Physical Media appeared first on Fernando Gros.

September 23, 2025

Out Of Print

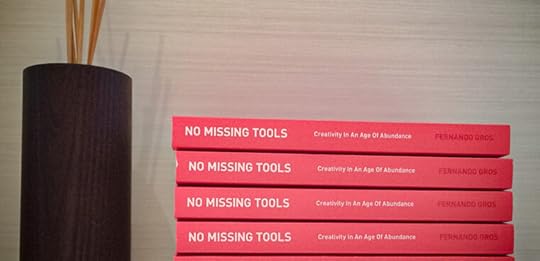

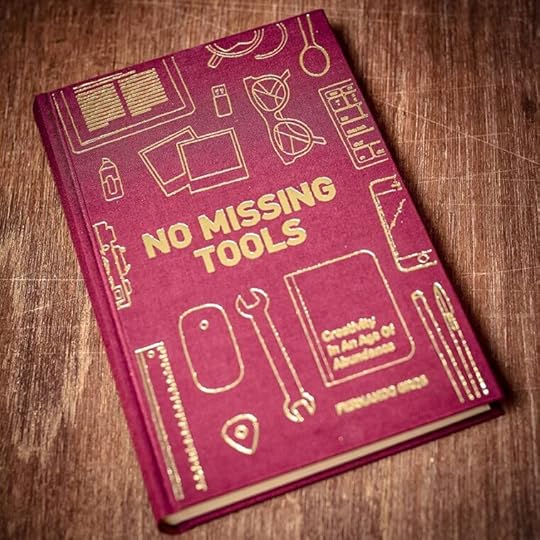

In April 2015, I self-published a book called No Missing Tools: Creativity in an Age of Abundance. My idea was to take the best writing from the first 10 years of this blog and put together a little e-book. The project grew, and what came out of it was a 65,000-word book that, in the end, very few people bought or read.

At the time I was enamoured with the idea of self-publishing. Some people I knew were managing to do it well. It felt like a natural extension of blogging. Like the obvious move for a small creative studio. I assumed the reach that social media gave me would magically help market the book.

But I decided that path without really knowing or understanding how the publishing world worked. I thought that if I tried to publish conventionally, I would give up out of frustration. Maybe that was true. My anxiety was undiagnosed at the time. Self-publishing was a form of self-protection.

If I knew then what I know now, I probably wouldn’t have self-published. I had a vibrant social media following and an active audience for this blog. Or, as agents and publishers call it, a platform. It was big enough and focussed enough to support pitching a narrative non-fiction book like that.

But I didn’t know any of that at the time.

I still carried the wounds from not finishing my PhD. Inside that story lives another book, another set of conversations with publishers, which were progressing, but on the assumption that I finished the PhD. I will probably always suffer from self-doubt. But it was very bad back then.

Not that I regret bringing No Missing Tools to the world. It was a big project. Not just a lot of words. But hiring a cover designer, a layout designer, working through various rounds of editing, and getting ready for sale, including a beautiful limited-edition run printed in Tokyo, was a massive experience. It taught me about how books are made, from the technology of bookbinding to the process of editing and compiling.

I also learnt there is so much I don’t know about how to market a product beyond my immediate audience. I could sell a book to someone who had been reading my blog for years. But getting books to people who hadn’t heard of me, into bookstores, or the wider reading world, was a mystery.

When I was writing the book, I was still working towards a specific vision of how I wanted to work. Most would call it content creation now. But I thought of it more in terms of a studio life. In Singapore and Tokyo, from 2011 to 2013, I built spaces that were made for work at the intersection of visuals and sound. I was podcasting and making videos. I was making music and photographs. And blogging about the experience of that creative work.

Some friends have suggested I came to that too early. That I was ahead of the curve. Maybe. It could also be that I gave up too soon. Or I wasn’t unrelenting about making time to grow that online empire. It’s clear to me now a lot of the people I tried to emulate back then were guys who didn’t take on the parenting responsibilities I had.

Or maybe I needed time to heal. To find a less frantic way to create. To approach writing in a different way.

I still have a studio-centric view of my creativity. But “making things for the Internet” doesn’t feel like a priority anymore. Social media has become a zombie technology. I have no interest in joining the cult of substack, which will of course become the inevitable substack exodus in a year or two.

And my writing has changed. I’ve worked on a memoir. I’ve published in some literary journals and hope to do more of that. I’m querying agents. I’m recreating this blog in a simpler format. I’m moving on.

The post Out Of Print appeared first on Fernando Gros.

August 30, 2025

Ageing Gracefully

My parents outlived probably any old person they knew when they were young. My mother passed away at 89. My father is still going at the same age. As a kid, I heard them paint a dreadful picture of what old age looked like. Back then, elderly people were immobile, senile, dribbling burdens on their families. It all sounded so bleak.

But I find myself wondering how old the people they described in such harsh terms really were. Perhaps only in their sixties. At most, their seventies. Nobody lived beyond that. Some survived into old age, but they didn’t thrive. They were just waiting to die.

Ageing Has ChangedLife for older people is different today. It’s not just that my parents demonstrated it. In Australia, life expectancy at birth in the mid-1930s was 63.5 years for men and 67.1 for women. It’s now 81.1 for men and 85.1 for women.

And it’s not just that people live longer. They are active for longer. Elderly people often cite physically engaging activities – walking, gardening, home maintenance, sports – among their favourites. People no longer see retirement as a moment to disengage but as a time to keep moving, keep connecting.

I saw this most strikingly while living in Japan. Studies into ageing well often focus on Japan because life expectancy is high. I didn’t just see elderly people active on streets –shopping, visiting museums, participating in community activities like park cleanups. I saw them riding bikes. Playing tennis. Taking to the ski slopes.

They weren’t just alive. They were living.

On Reaching Old AgeWhen it comes to reaching old age, getting to 75 or more, instead of just dropping dead before that, a lot of what we can do boils down to simple, non-negotiable habits. Eating well. Doing some exercise. Getting enough sleep. Of course, there is a genetic lottery at work. Some people are born with a greater chance of reaching old age. But some of the variables are within our control – what we eat, how much we move, and how well we rest.

But if we reach old age, how do we continue to thrive? How do we avoid becoming the sad potato in a dark corner my parents once described?

The non-negotiables then take on an internal dimension. They reflect mindset and mental health.

We need to keep learning, growing, staying curious about the world. We need adaptability, the ability to respond as our bodies and abilities change. We need to be connected to other people, not just friends and a social circle, but having open, vulnerable relationships. And we need generosity to share what we have and what we know.

So what do we do if we haven’t reached old age yet, but we can feel it marching inexorably towards us?

Taking Ageing SeriouslyWe can start with those three non-negotiables: sleep, diet, and exercise. We can take a good look at our habits. Audit them. Track what we do. Keep a journal. And talk to those we love and trust.

We need an honest picture of where we’re at so we can map a path to where we’d like to be. Because often the changes we need to make aren’t always simple additions and subtractions.

Just trying to add half an hour of sleep might seem impossible if our life doesn’t afford us the time. We might need to rethink how we do our evenings. Or maybe we’re locked into a morning schedule that sees us rising too early.

We probably won’t get to healthy eating by simply cutting out a treat now and then. We might need to go deeper into our relationship with food. Or notice how the relationships we’re in shape when and what we eat. Or how much we drink.

Exercise might seem like the easiest puzzle to solve. Go for a jog. Hit the gym. But much of what matters looks less heroic. Being able to stand. Or get off the ground. Pilates, yoga, or other mobility training would help.

These are not just exercises in habit and effort, tiny experiments in personal development; they are learning journeys.

A Life of LearningAnd that’s the point. The sooner we buy into lifelong learning as a commitment, the better. Because the world won’t stop surprising us. It’s very unlikely that anyone over 65 grew up regularly using a computer. But now everything from banking, to shopping, to dealing with government involves apps, devices, or online interaction.

Or look at how we stay informed. In just a few generations we went from morning and afternoon newspapers, a few radio stations and a handful of TV channels to hundreds of choices on cable, before those gave way to streaming, podcasts, and online news sites.

Being learning oriented also helps us be adaptable. And adaptability matters because we keep changing. We decline in some ways: speed and strength diminish; memory becomes less reliable. But we can grow in others, especially wisdom and self-knowledge.

Connection helps us with this. Not just having a social circle, but deep emotional bonds with people we can be honest and vulnerable with. Having friends is good. Having good friends is better.

Making friends feels harder as we get older. Mostly we make friends by joining and giving. These are easier when we’re young. We get introduced to more groups of people. It costs less to share what we have. Later in life, it feels riskier. It’s harder to remain open and emotionally vulnerable. And society trains us to be less generous.

A Generative LifeBut generosity might be the most important part of all. As we age, it becomes time to share our knowledge. Encourage others. Share our things.

It might well be that generativity – that sense of being part of a longer moment in history, of actions that echo beyond us – is what brings meaning and satisfaction to this crowning stage of life.

The post Ageing Gracefully appeared first on Fernando Gros.

July 17, 2025

Conversion Experiences

The latest edition of The World’s 50 Best Restaurants has just been released. The appearance of Sézanne at number 7 immediately caught my eye. A couple of years ago, I ate at this restaurant in Tokyo’s Marunouchi district. The accolades seem well deserved. It was one of the most remarkable experiences of my life. There was no menu. Just a card with a statement of the restaurant’s philosophy, a list of suppliers, the date, and the chef’s signature.

In his book Unreasonable Hospitality, Will Guidara describes a visit to Restaurant Daniel in New York that changed his life. It wasn’t just a few nice dishes. Or a break from the sadness in his life at the time. It was an experience that changed his thinking about how magical a meal can be. Guidara went on to be the manager of Eleven Madison Park, which at one time was listed as number one on The World’s 50 Best Restaurants list.

My meal at Daniel wasn’t quite as life-changing. But it was something totally out of the ordinary, in the same way that eating at Sézanne was exceptional. Everything felt perfect. Not perfect in a pretentious or critical way. Perfect in a comforting way. Like every potential problem had been predicted, considered, and solved in a way that allowed you to focus on nothing else but the food in front of you and the company by your side.

Some experiences transcend their immediate context. The meal is suddenly more than a meal. We’re not just tasting food. We’re sensing something deeper about how we should relate to each other, to the place where we are, to all living things.

Typically, we associate these kinds of transcendent experiences with the arts. Music concerts in particular come to mind. Fans lost in the sight of their idols and the allure of their favourite lyrics.

But transformative moments can come at us in the midst of any human pursuit. Like eating a meal in a restaurant. And when they do, it’s a conversion experience. We are changed. It’s a joyous thing. But it’s also a problem.

One Way to Come at ConversionMost people will never get to eat at Sézanne or Daniel or Eleven Madison Park. These kinds of restaurants are not just very expensive. Sometimes even getting a reservation is difficult.

Which is a shame because what these restaurants do is more than just cook expensive ingredients, or serve them in attractive ways in lovely rooms, tended by helpful and well-trained staff.

The best restaurants bring a philosophy of life to the table.

It’s not about whether the steak is perfectly cooked, the wine is at exactly the right temperature, and the waiter knew where one specific ingredient in one specific dish was grown. That’s just the mechanics of the meal.

It’s about whether the food touches your soul.

Or substitute something else for food. Music, dance, poetry, cinema, nature. Maybe it isn’t something you experience externally but rather as a feeling you have while acting in the world. Perhaps while making something, working in the garden, caring for someone, or simply falling in love.

Conversion and the Limits of ExplanationIt’s tempting to think the best restaurants are like normal restaurants but just a bit better. Or more expensive. Or more posh. Or something.

But places like Sézanne, Daniel, and the like aren’t really on a continuum with your local cafe. Yes, both serve food. But it’s like comparing a wedding band to a symphony orchestra. One never becomes the other. And if all you’ve ever heard is wedding bands playing covers of old pop songs, you can’t really imagine what sitting in a concert hall hearing an orchestra would feel like.

You have to experience it.

And this is the problem with conversion experiences. You’ve either had them, or you haven’t. There’s a hurdle. Or maybe a chasm. And it’s hard to build a bridge made of words to help people over that gap. There’s only so much you can do with explanations.

This matters because once you’ve had a conversion experience, it feels obvious that things should be a certain way. You believe something is possible that others might consider impossible.

For example, Will Guidara talks about a system they developed at Eleven Madison Avenue. When you arrived at the restaurant, the person who greeted you was the one who had taken your reservation. And they greeted you by name. No having to explain who you were and that you’d booked. They had looked online for what you looked like. And when it was time to go, they had the bill ready so you didn’t have to ask. By the time you got up to leave, someone was already waiting near the door with your coat.

If you haven’t ever experienced service like that, it seems like some far-fetched fantasy.

Mind the GapThere are times when we find ourselves caught in that gap. We’re on one side of the conversion experience talking to someone on the other side. What do we do?

Increasingly, I’ve come to wonder if we can even talk across the divide. Maybe all we can do is simply point to the gap?

When I wrote recently about sandwich making and the Coursification of Everyday Life, I was keenly aware of the gap. I dropped some names. I could’ve dropped a lot more. It could’ve become a foodie bragfest. But what matters isn’t ticking places off some exclusive list.

It’s the experiences.

Maybe all we can do when we find ourselves trying to straddle the gap is invite people to try? To encourage them towards the experience?

If the curiosity is there, then maybe they might have their own conversion experience. And if the interest isn’t there, then no number of words and explanations will bridge the gap.

Loose and TightWhat this allows us to do is to hold our conversion experiences loosely and tightly at the same time. Loose in the sense that we don’t feel obligated to explain them or fragile when we feel they are being criticised. But tightly in the sense that they still have deep meaning for us and continue to be our compass for how to live well.

I think about some of the conversion experiences I’ve found myself justifying over the years. Like David Allen’s approach to Getting Things Done. Marie Kondo’s approach to tidying. My own spiritual journey in and out of organised religion. My love of Japanese calligraphy or losing myself on a ski slope. Even the passion with which I approach brewing a cup of coffee. And, of course, the seductive power of a spectacular sandwich.

All of these mean a lot to me. But they might well seem weird, obtuse, or ridiculous to others. And that’s okay. They don’t have to make sense to people who haven’t gone on a journey with them.

We can point to our experiences, to what it felt like to pursue them, how they changed us, and what it means now. But sometimes all we can say is, “I don’t know. Maybe just give it a try.”

The post Conversion Experiences appeared first on Fernando Gros.

July 4, 2025

The Coursification Of Everyday Life

The ad found me while I was scrolling through Instagram with a mix of boredom and resentment. The 10-chapter course, “Flavour-Packed Sandwiches”, promised to help me master “the fundamentals of sandwich design and raise my sandwich game.” Or something like that.

Apparently, “the thing about a sandwich is, every single bite you take is the exact same. That means every bite has to be perfectly thought out and layered.”

If the stakes are so high for a humble sandwich, then a programme of in-depth study feels not only justified but essential. Where do I sign up?

I wondered if the course was specifically for people who run cafes and restaurants. But no. It was for anyone “in pursuit of sandwich perfection.” Amateur or professional. Take my money now.

Maybe I’ve been doing sandwiches wrong my whole life and this is my last chance to raise my game. I can’t afford to be some kind of sandwich-making imposter.

The Coursification of LifeI’m a firm believer in life-long learning. Education is the path to freedom. Courses can be a powerful way to enhance our skills and improve our lives.

But lately, I’ve started to notice that every domestic task has been coursified. Even the most mundane and everyday chores, like making a sandwich, now come packaged as snazzy courses, with high-resolution graphics and anxiety-inducing marketing copy. Courses for sewing. For cleaning. For the most basic of DIY repair.

It makes me wonder how we ever learned anything before.

A Life of Sandwich MakingMy sandwich journey started with watching my parents. We ate some kind of sandwich every day. Chile has a spectacular sandwich culture. But it wasn’t just things between slices of bread.

I approached learning about sandwiches the same way I approached learning about gardening, or mending clothes, or repairing things around the house. With childlike curiosity.

It might sound like I grew up in some kind of child labour trade school. Okay, it was like that at times. Maybe a little too often. Working-class childhoods were like that back then. But I also went to where my parents were. Gravitated to what they did. Absorbed the knowledge they offered.

That curiosity persisted into adulthood. Every delicious and compelling sandwich was a learning experience. The steak baguette from Robuchon Tea House in Hong Kong, the haggis toastie I used to buy from a food truck opposite Arisugawa Koen in Tokyo, or the banh mi from my local Vietnamese bakery in Adelaide. I would study each sandwich to see what made it work.

Perhaps I’m making my journey sound luxurious and extravagant by name dropping and location bragging. But the board brush strokes of this kind of journey – youthful experiences, adult experiments – are not unusual. Many of us learnt this way. Trial and error. Replicating what we saw and loved. Making it our own.

What Changed?But did we always learn that way? Or did something change between then and now?

The Coursification of Everyday Life is more than just the transmission of information. We’ve always had books and training manuals. Newsagents used to be full of magazines with DIY examples, patterns for sewing and knitting, recipes, and even ideas for making sandwiches.

Coursification suggests something is missing beyond just the transmission of information.

The “Flavour-Packed Sandwiches” course suggests we lack something beyond recipes or suggestions on how to plate the things we cook. We lack the concept of what makes a sandwich great. A cultural and philosophical deficit. We’ve reached adulthood missing a fundamental building block of civilisation.

Fragmented Bonds of LearningI exaggerate. But maybe only a little. Perhaps something has fundamentally changed. Fractured. Or at the very least fragmented.

That working-class environment I grew up in was based on the idea of the master and the apprentice. You learn by observing, watching, being shown how to do things. You don’t just acquire discrete bits of knowledge. You are schooled in a system, a philosophy, a way of making things. It’s a path to mastery.

Learning is different today. The student’s journey is what matters. They piece together the knowledge they need as they need it. There is no overarching philosophy, just tasks that need to be completed. The student directs their learning experience.

I’m not going to suggest what I grew up with was better. Comparing how philosophies of education have evolved would be a huge task. And there was plenty wrong with the kind of learning environment I grew up in. Little room for individual creativity. Lots of space for abusive behaviour from teachers and those in positions of authority.

But I still finding myself wondering whether the coursification of everyday life is something that should give us pause.

Have we witnessed the breaking of the social bonds that connect education to participation in society more broadly? Have we been so fixated on coaching kids for success in the competitive worlds of academia and work that we didn’t prepare them to live self-directed domestic lives?

I ask these questions with trepidation, knowing that, in our moment, those who robe themselves in the values of community and tradition are often wanting to drag us back to darker times.

But the questions persist.

The Amplification of ComparisonI also wonder why it all matters so much. Who cares if I’m not maximising my sandwich game? Why should I worry if one bite of my sandwich isn’t as magically identical as every other bite?

Whose judgement and shame would I be experiencing?

In one sense it would be my own shame. My own expectation of being excellent at every aspect of life. But also, there is the infinite chorus of voices, the people we’ve met, the ones we haven’t but who still speak (or scream) in our direction from the various corners of the internet.

Even if our sandwiches are perfectly fine and deliciously tasty, there’s always someone out there whose sandwiches look better, in person or in photos posted online, and so we sign up for another course.

The post The Coursification Of Everyday Life appeared first on Fernando Gros.

May 17, 2025

Zombie Technology

1.

There are so many types of zombies that it’s hard to pick a favourite. Zombiepedia lists runners, crawlers, stalkers, screamers, pukers and exploders, to name just a few. I find myself captivated by the zombies in 28 Days Later. Entertained by the zombies in World War Z. And surprisingly amused by the zombies in three or four of the best Resident Evil movies.

Whatever version of zombiedom we’re talking about, all zombies share common features. They are undead. Which is to say, they move and act, but in a soulless way that lacks the defining features of human existence. Zombies are humans stripped of humanity.

Today’s technology, including vast swathes of the internet, feels zombified. It’s not dead. But it’s not really alive either. It just continues to exist. Stalking us. Tempting us to take unhealthy risks. Ready to pounce on our weaknesses and exploit them. Making us go through life on the defensive. Always apprehensive. Trying to protect ourselves and our loved ones.

2.

We all have that precious list of books that “really made a difference”. One of those for me is Liquid Modernity, by Zygmunt Bauman, which came out in 2000, amid the flurry of books about post-modernity. It was a book I read and reread during the zenith of my academic years.

One idea that particularly stood out was the concept of zombie words. Bauman suggested that many of the words we use in every day discourse feel like they mean something. But they are actually empty. Their meaning has evaporated. They refer to cultural concepts that are no longer alive. Yet we continue to use the words.

We use them just because we use them.

For Bauman, “community” is one example of a zombie word. We hear all sorts of things – schools, churches, even online spaces – described as communities. But social life is becoming ever more fragmented and individualised. We are increasingly lonely. We struggle to find a sense of belonging, shared purpose, or mutual accountability.

We say community when, really, we mean something more like people who are lumped together in a common category.

Technology has started to feel like a zombie word. It used it to describe the vanguard of innovation. Solutions for better living. Progress towards human freedom. Now it’s more like something that traps us.

3.

The early internet felt vibrant because the barriers to entry were low. People couldn’t start newspapers. Buying and running a printing press at scale was expensive. The costs rose for radio and again for TV. Both came with increasing amounts of regulation as well. But starting a website cost nothing. And there were no rules you needed to comply with.

Websites are now governed by opaque and mysterious rules that decide whether people can find a page via a search engine. Try to share a link on a social media platform and there’s a good chance your followers won’t see it. Your account might even get punished for trying. No wonder most websites look the same and people who have created stuff have to play weird games to get people to notice their work.

None of this is likely to change in the short term. The motivations of those who own the internet experience – the people behind Google, Meta, X, SubStack, YouTube, TikTok, and the rest – are so massively misaligned with the interests of people who create the stuff that it makes the internet interesting.

4.

Tech came for music first. But no one really cared because they loved filling their hard drives with free music. Tech came for designers as well. But free fonts were fun. Photographs and artwork were used all over the internet without attribution or licensing. Finally AI came for everyone who had ever published anything anywhere.

But by then the apologists for the elision, of artist’s rights had done their work. We were told “great artists steal” and “everything is a remix”, which laid the groundwork for the notion that anyone could be an artist if they just asked AI the right questions. By then, the makers of these tools weren’t even apologising. They admitted their business model couldn’t work if we protected copyright, and they spoke of artists in air quotes.

5.

The infrastructure of technology belongs to billionaires. But it wasn’t always like that. The first internet service provider I signed up with was a side project run by a friend of a friend. Hosting for a few web pages came free. There was no social media. There were barely even search engines. Mostly, you followed links from one site to another. Surfing the web was what we called it. Discovering interesting pages was a combination of luck and skill. Mostly luck. Some people connected their life online with their professional existence. Academics, in particular, were doing this from very early on. But no one was making money from the internet. Having a presence on the web was a kind of hobby. A way to learn. Or just something fun to mess around with.

Now we are just data points in a vast money-making machine. The experiences we have with technology might not be pleasant or even all that useful to us. They are shaped to serve the needs of those who own the online tools we use. Increasingly, those needs extend beyond just making more money and include the dissemination of misinformation and the acquisition of political power. We are pawns in the games oligarchs play.

6.

2013–2023 was the decade of technological zombification. Platforms became increasingly hostile towards their users. There were precious few innovations. The ones pitched to us – crypto, NFTs, Web3, AI – promise abstract and unrealised benefits, demand a cult-like belief in eschatological salvation, or are simply tools for grifting and corruption.

Gamergate was a small controversy in the greater scheme of things. But it broke the internet. Gamergate mainstreamed online harassment and trolling, including the strategy of undermining civil discourse online. The assault on DEI, so-called “wokeness”, and even democracy itself has roots in Gamergate.

After Gamergate, the internet became harsher and more misanthropic. But the tech world in general became more cynical and unable to brook criticism.

Nothing feels more cynical than the claims that we are on the verge of Artificial General Intelligence. It takes a monstrously low estimation of what it means to be human to claim the current crop of faltering, large-language models are in any way close to replicating human intelligence. And yet here we are.

7.

And this is really the crux. The internet doesn’t exist because someone decided to build a social media platform or a search engine. It exists because people decided to share their lives online. Post their photos. Convey their knowledge. And seek out human connection.

The web emerged from millions of small experiments in personal expression. Harvesting all that creativity for the enrichment of a few is one of the greatest economic injustices in human history.

If we want an alternative, an internet for the rest of us, then it has to start here, with our need for human connection and with addressing the moral injustice at the heart of technology’s zombification.

Maybe I am excessively prone to optimism, but I believe there are still a few ways we can carve out spaces to use technology for human liberation.

8.

Harnessing technology feels like a lifeless chore when our efforts are disconnected from the joy of relating to other humans. Working to build human happiness yields joy. Working to appease an algorithm never does. Software updates that only take care of the device seldom yield joy. Tweaking a sentence so it lands better with a reader feels rewarding. Adjusting your words to appease a search engine leaves you feeling devalued.

Technology makes sense in so far as it fosters and supports human connection. We don’t need a forum of rage lined with advertisements. We need a digital representation of properly functioning society. We need tools that help us build that society. And we need them priced equitably and made accessible to all.

9.

Imagine if your diet consisted of eating only what was on sale at your nearest shopping mall food court. It’s hardly a prescription for a healthy body. But that’s the equivalent to outsourcing your information diet to social media algorithms and trending topics. Like the food we eat, the information we consume needs to be nutritious. Fast food and sugary drinks might be okay now and then, but we can’t thrive on that stuff.

One of the things tech’s era of zombification ate was expertise. Far from being authoritative articulators of evidence-based knowledge, experts are now just one voice in the noisy post-truth public discourse. It’s tempting to imagine expertise doesn’t matter anymore when Wikipedia makes everyone feel like all the world’s knowledge is at their fingertips. At least until we have to solve really complex, real-world problems – like how to face a pandemic, respond to climate change, or reconfigure the world economy when a large country goes rogue.

We need to calibrate our information diet as carefully as we control our nutritional diet. Both require informed choice oriented towards healthy living and human flourishing. Read like you eat. Like your life and longevity depend on it.

10.

There is only one alternative to tech eating art. We have to pay. We have to pay for music, films, creative writing, design, art, photography. We also need to support the institutions that provide the teaching and research that make these kinds of activities possible.

And those of us who make things also have to find ways for people to pay us.

Perhaps the greatest lie on the internet is that there is non-commercial space. Anything you post online is making someone money. Every tech company makes money from what you share online, whether you notice or not.

We need to stop shaming people who want to be paid for their labour.

11.

Technology is a tool to enhance real-world experiences and not an end in itself. But technological zombification asks us to be subhuman.

Facebook’s Meta project was perhaps the most dystopian example of this trend. Virtual reality as a way to make digital gaming more immersive, or perhaps to make online meetings more interesting, is a worthwhile idea. But Facebook wanted more. If all the money in the world isn’t enough, then why not push everyone into a virtual world where wealth and power are not constrained by real-world limitations like how much water our planet has?

From seasteading and crypto-based smart cities to virtual reality, colonising Mars or replacing every human worker with an AI, the tech fantasy involves restarting civilisation in the absence of everything that civilised us – rules and culture and religion and some sort of relationship to the natural order.

I’m not going to Mars. My guess is you aren’t either. This earth is it for us. Let’s put it first and live a big and wonderful life enjoying what it has to offer us.

The post Zombie Technology appeared first on Fernando Gros.

April 27, 2025

The Number Is Meaningless

Apparently, Seth Godin has reached 10,000 blogposts. He’s been at it for 25 years. He says that’s over 3 million words. And he posts once or twice a day. While the longevity of this practice is admirable, I think those numbers are largely meaningless.

I’ve been blogging for over 20 years. I have nearly 2,300 blogposts. At first, I posted nearly every day. But for years now, it’s been more like three to four times a month. Because many of my blogposts are long, I estimate that’s over 2 million words. And while that journey means a lot to me personally, I also think the numbers are meaningless.

Beware of FillerI say that because many of those posts are not very good. They have no more to say than the kind of thing we might post in a tweet or Instagram caption. A lot of them were just a comment on an interesting link or video. Or an update that long ago lost its importance. They aren’t really part of a story. Or a container for an interesting idea. Or something that signposts a significant experience.

They’re just filler. They’re there because they’re there. They’re words I once wrote. Unlike entries in a journal or emails, they are public. But no one is reading them again. Not even me.

As much as I love writing and sharing blogposts, I’ve come to hate running this site. There are so many problems. And fixing them is like sticking my hand in a jar full of wasps. I can’t bring myself to address the problems without recoiling from the expense, frustration, and potential pain.

How To Start AgainIf I were starting a blog from scratch, I would establish a consistent formatting style and a limited set of tags and categories. I wouldn’t use third-party apps to serve up core content. I’d have consistently formatted header images for every post.

And I wouldn’t put myself under the obligation to keep every post up forever.

I never started blogging with a clear definition of what this practice is or how it should be done. Blogging was an experiment in self-expression. It emerged organically. Only later was it codified. It got weighed down by people’s ideas about how to do it well. Whether well meant being authentic. Gaining an audience. Or some kind of commercial success.

Now I’m tired of being weighed down.

How To Find MeaningWhat feels meaningful isn’t the number of posts or the years I’ve posted them. Crossing the 20-year threshold really brought that home.

What matters is the legacy. The cumulative meaning of the work. The words that continue to resonate.

I’m not sure why we came to believe that blogging needs to be an uncurated enterprise. Editing and omission are essential parts of creative work in most other pursuits.

When I look at old blogposts I wonder, Should I fix typos? Should I rewrite unclear sentences? Should I note where I changed my mind? Or where something I tried didn’t work out? Or did, but in a surprisingly different way from what I expected?

And for many old blogposts I simply wonder what the point is of keeping them. Some old posts are little more than a link to something that no longer exists online. A gloss on some long-forgotten moment.

Blogging As PerformanceA blog is different to a book, for example. I think of it as performing a song live versus making a recording. In the studio, you try to get a lot closer to perfection. Or to the best you can do in every small detail. There’s a lot of polishing to create the biggest impact for something that will (hopefully) be heard many times.

But there’s also a big difference between a live performance and a jam or rehearsal. The live performance is also polished. Choices are made to make hearing and seeing the performance memorable. Artistry and stagecraft matter.

If blogging is akin to live music, there are still critical choices to be made. After all, as we blog we decide which experiences and ideas to share. All along I chose to be selective about what I shared about family, for example. I wrote about some health issues but not all of them. I didn’t mention every creative project. I mostly didn’t write about clients or collaborators.

Which brings me back to those 2,277 blogposts.

Most of the gnarly problems are with posts from the first 10 years. If I only kept 30 or so per year from that decade, I would cut well over a thousand posts. I could even keep most of the recent posts and still keep things lighter.

I’ve procrastinated for so long over this decision. The problem wasn’t technical or tactical. It was always clear that a smaller set of articles would be easier to deal with. Less work to set up. Easier for readers of the site to navigate.

Escaping Our Own RulesWe make rules for ourselves. Maybe they make sense at a certain point in our lives. But then circumstances change. We grow. We evolve. We age. Maybe the rules are no longer helpful. Maybe they become prisons for us.

Sometimes we have to escape.

If blogging were a game to play for fame and fortune, I failed a long time ago.

I don’t write in order to have a blog. I write in order to make sense of the world. I’m not here to abide by any of the rules we might make up for blogging or any of the prizes bloggers might have been promised over the years.

Some of my words live here. Some are published elsewhere. Some stay hidden on hard drives and between the covers of the many notebooks that live on my shelves.

So which words do I keep online?

The ShedRecently, I pulled down the old shed that lived in a corner of my garden here in Adelaide. I never loved the structure. From the moment I first saw it, I knew it had to go. It was old, dusty, and cold. I dreamt of something nice. A place to work and play.

The years passed, and the shed was used mostly by my mother to store garden tools and pots. She would come by from time to time when I was away and tend to the garden. The shed reminded me of her.

But something that lay unused, collecting grime and spiders, is a poor homage to someone’s love.

I cleaned up her favourite rake and found a prominent spot for it in the garage. I bought a photo album and filled it with the nursery cards she kept for everything she planted in the garden.

A new little cabin is going up where the shed was. A clean place to write and have new dreams. I will put that little album next to a photo of my mother in the garden on a shelf there when it’s all done.

That’s how you build a legacy and keep a dream alive. It’s not by keeping everything in its dusty place. It’s by renewing and curating and bringing to the front the things that really matter. The things that drip with meaning and significance. That which moves you matters.

EpilogueThis is the first of three articles written as I convert this site and blog from dynamic content delivery with WordPress to static site generated with Hugo.

1. The Number is Meaningless

2. The Design Matters

3. Embrace The Tech You Can Master

The post The Number Is Meaningless appeared first on Fernando Gros.

April 8, 2025

On Leaving Melbourne

I wrote about moving to Melbourne in July 2021. The ongoing pandemic, the postponed renovation plans for my house in London, and Australia’s closed borders, all suggested that delaying the move would be wise. I didn’t really know what to make of going back to Australia or settling in an unfamiliar city. I wrote:

“To me, it feels more like another expat relocation. Melbourne is a place I’ve visited only twice and only for a few days each time. And as much as I love visiting Adelaide and miss the regular cadence of trips I made there, Australia stopped feeling like home a long time ago.”

Then, in 2023, a year after I had arrived in Melbourne, this theme of feeling like an expat in my home country continued to linger.

“Melbourne is a new city to me. I visited once, 25 years ago, but didn’t know the city or anyone who lived here. I had all the usual expat-type questions. Where do I shop for food? Get a haircut? Buy clothes? It was familiar in a way, since I know Australia, the way you know people you went to school with but haven’t seen in years, but unfamiliar in the kind of detail that makes daily life easy.”

Nearly two more years have passed and I’m packing up my apartment in Melbourne. That feeling of disconnection has never really gone away. I did my usual things. Tried to find a favourite cafe, a hairdresser, a cool guitar shop; joined some galleries and museums; explored a few food markets; went to some events; and walked, a lot.

But I leave Melbourne after nearly three years, having made no friends, feeling like I never really met anyone, and never getting to know the city deeply.

A large part of this is my own fault. When I arrived, the city was still partially paralysed by the pandemic. My own circumstances found me often away from the city. My mother’s illness. Her passing. Frequently travelling back to Adelaide to help my father. Trips to the US to visit my daughter at college. Family holidays back in Japan. I rarely got to spend three weekends in a row in Melbourne.

And unlike Tokyo, London, or Hong Kong, Melbourne isn’t a city that attracts visitors from my circle of friends. I’ve met up with way more folk whose travel to Japan coincided with mine than all the number of people I know who visited Melbourne during my years here.

I’ll leave with some good memories. Live music, like Taylor Swift’s Eras Concert at the MCG, IVE on their first world tour, and a particularly special live set from St Vincent on the rooftop of the Crown Casino. I saw lots of good films here and enjoyed several exhibitions at the National Gallery of Victoria and the ACMI. I will miss my weekly trips to South Melbourne Market. And afternoon walks along the Yarra and through the Botanical Gardens.

But compared to everywhere else I’ve lived, that’s a very short list.

I lived in Singapore for only two years. And yet when I look back on what I wrote about leaving that place, the “the cycle of lasts”, there’s an emotional heft around saying goodbye to people and places that I don’t feel about leaving Melbourne. Back then I wrote:

“I can still recall the sound of every last door closing, from Sydney, to London, to Delhi and Hong Kong. I can still recall the smiles thorough the sadness of all those last goodbyes and best wishes. And I can still feel the heavy heart and the lump in my throat every time I walk down the skybridge from what had been my home airport, one last time, before pausing to touch the airplane’s door, then boarding and looking out the window one last time at the city I’m leaving behind and all the people who will awake the next morning and then get on with their lives without me.”

I felt the same way about closing the door on Tokyo and both times I left London. But I’m not sure I will feel that way when I close the door on Melbourne and board my final flight to leave this place. Perhaps because the city and its people still feel like strangers.

The post On Leaving Melbourne appeared first on Fernando Gros.

March 13, 2025

Repair As A State Of Mind

The van pulls up under a grove of trees outside the local library. Two older men get out. They put up a small marquee and a plastic table by the side of the van. Then they open the shelves installed in the van to reveal a dazzling array of tools and spare parts. Finally, they fold out a sign to say the Toy Hospital is open for patients.

All across Japan, toy hospitals exist to repair broken and beloved toys. Some are mobile stations like this one I used to see near my home in Tokyo. Others have permanent locations. There is a Japan Toy Hospital Association that lists more than 650 toy hospitals and “has about 1,700 ‘doctors’ working on repairs”.

The toy hospitals also serve social functions. They help older men make friendships and retain a feeling of being useful to society. In most countries, men over the age of 55 don’t ever make new friends again. Loneliness for older men is a huge problem that manifests in a range of health issues.

Repair Is a Way to Resist ConsumerismThis isn’t a “Japan-only” story. Repair cafes are popping up around the world. These are places where people gather to fix things and get advice on how to do repairs. The venues usually have tools available for people to use and experienced repairers on hand who can offer advice and suggestions.

A recent New York Times Wirecutter article highlights that these repair cafes tend to have a fun, encouraging, and educational sense of community.

Repair cafes also serve an important economic and social role because they reduce waste along with the emissions involved in making and shipping new products.

An Expression of Ownership“If you can’t fix it, you don’t own it” is the bold claim that opens iFixit’s Repair Manifesto. iFixit is a company that makes and sells tools for repairing tech devices like computers, smartphones and gaming devices. They also have a big library of free repair guides.

Many of the products in our homes can’t be easily repaired. Some are made so they can’t be opened using conventional tools. Few, if any, places offer professional repair. And access to manuals and schematics is limited or simply not available.

This pushes us to buy new products when older ones could be made to last longer. It also discourages us from learning to repair our own belongings. It’s bad for the environment. And it robs us of the satisfaction that comes from being able to fix things or keep enjoying possessions that have a cherished and welcome place in our lives.

Oriented Towards RealityMaintenance is the natural order of the world. Things can only be new for a very short time. For most of its life, the stuff around us is aging, decaying, and in need of maintenance.

This is good. Welcome. Something we should embrace.

Maintenance is the other side of taking care of the things in our lives. When they break, we can take of care of them through repair. Or we can try to avoid having them break through maintenance. Both go hand in hand and share the same tools and philosophy.

Maintenance – taking care of something – is the ultimate act of gratitude. It is being thankful by making sure something is ready to perform. Fit for service. In excellent condition. Maintenance is love expressed in craft and process.

Maintenance is also grounded in reality. In observing and understanding how a thing works, how it wears, and how it can get damaged. You have to understand how a thing works to maintain it. You also have to care. To be the kind of person who notices and acts when needed.

Repair Is a Form of Moral ActionBeing the kind of person who repairs things involves taking a moral stance. It’s an economic and environmental stance. It’s saying that it’s better to invest in maintaining what we have instead of always dumping old things and digging up resources to make new ones. It’s being oriented towards learning and observation. It’s understanding how things work and learning how to fix and maintain them. And it asks us to be oriented towards action. Not to wait till things fail and then doing nothing about it beyond getting the credit card to make a replacement purchase. We become proactive about making things work.

Repair and maintenance are ways to bring calm and order to a world prone to chaos and entropy. By choosing to value some things, to not allow them to wallow in disrepair, we demonstrate our values. This matters to me, so I take care of it, because in turn it will take care of me, allowing me to express who I am.

Perhaps most important of all, the repair and maintenance mindset teaches us that things can be fixed. Breakage and failure need not be final. It’s easy to give up on things. Or get caught in lament over the faults they acquire. But very often, trying to repair pays off. Broken things can be fixed.

The post Repair As A State Of Mind appeared first on Fernando Gros.

March 3, 2025

The Real Work Of Midlife

What is the point of being middle aged? Like, what are we trying to achieve in midlife? The purpose of youth seems to be well defined. Learn. Experience things. Discover the world. Old age is also defined. Share wisdom. Mentor. Volunteer. Help hold communities together.

But what are we supposed to do with the middle of our lives? Especially since the middle can last so long. Some say you’re middle aged by your thirties. Most would consider those in their sixties to still be middle aged. Even if we round off the edges, it’s still a lot of life. Most of our adulthood. The bulk of our most productive years.

Sometimes, it feels like midlife is defined in terms of accumulation and obligation. Climb the career ladder. Acquire a home. Then try to get a bigger home. Fill it with a progression of ever larger TVs and appliances. Find someone to marry. Have kids. Send them to school. Then university. Buy and do. Spend and fulfil.

I’m oversimplifying. There is more to it. But it can still feel like that’s all there is. Especially when we go through crisis after crisis. Relationships break under the strain of it all. Friendships fray. Marriages break down. Finances falter. It can feel hard to find meaning in it all.

It can be easy to lose sight of the most important purpose of midlife.

In our quiet and reflective moments, we know we will get older. We might not care to dwell on the way old age and, eventually, death are coming for us. But we know it. Unfortunately, our sense of how to prepare for it feels limited to questions about money and resources, as if it’s hard to think about life in anything other than capitalist terms. But this isn’t an essay about savings and pensions and superannuation.

Instead, it’s about how the way we understand ourselves needs to evolve in midlife. To prepare for later life, we need to solidify what we learned in early adulthood.

Redefining SelfIt’s not just that we will perform less well as we age. It’s that some of the things about ourselves that we’re proud of might become hinderances in our later years.

Maybe you’re proud of how much you can carry around in your head. You tell yourself you’re good at remembering names, internalising directions, recalling dates for appointments and commitments. But what will you do when your memory becomes slower and less reliable?

Or maybe you’re proud of how quickly and efficiently you can move through life. You can shower and get changed in no time. You can slice through airport security lines and supermarket checkout aisles faster than anyone else. You can smash through chores and checklists like a knife through soft cheese. Until, of course, you can’t.

When we’re a young adult, being the smartest person in the room, the one making the cutting and insightful comments, can be an asset. Once we’re old, that kind of behaviour can feel combative and heavy handed.

When we’re younger, being self-reliant and independent can feel like a strength. But as we age and life gets harder, being open to receiving help can make life lighter and better for ourselves and those around us.

The big challenge of midlife is that as the world encourages us to run fast, do much, achieve a lot and acquire everything, we need to slow down, reflect, understand our values. We need to make hard choices about where we invest our time and who we share it with.

“Much of the work of midlife is learning to tell the difference between people who are still dealing with their issues through you and those who are dealing with you as you really are.”

– Richard Rohr, American priest and writer

Most of all, we need to consider what it will mean to be older. To inhabit an older body. To what extent we will accept the narrowly defined roles our society stipulates for older people.

Freedom and HappinessThis needn’t be a negative experience. In fact, research suggests a lot of people become happier once they reach their mid-fifties. And this happiness can extend well into old age.

This happiness comes from having fewer priorities, a clearer sense of who we are, more choice over who spends time in our orbit, and less drama in our day-to-day existence.

There’s a lot of freedom in being honest with yourself over who you are and what your life consists of. This includes the freedom to love more deeply and openly. And the freedom to be more truthful.

“I’ve long thought of old age as a time when all that’s left is to tell the truth – trying to remember to tell it in love. It’s liberating to be at a point where I no longer need to posture or pretend because I no longer feel a need to prove anything to anyone.”

– Parker J. Palmer, American educator and activist

Being more open to the world and less inclined to hold onto grudges and prejudices helps us be less self-obsessed and better able to help others. We can be of greater service to those who will follow us in whatever work and craft we have devoted ourselves to furthering.

The achievement and acquisition model of midlife feels burdensome. There’s no freedom in comparison and competition.

But by making time to look calmly at ourselves and start to imagine our future honestly, a more satisfying picture emerges.

Eternal ActivitiesOver recent years I’ve looked for the eternal activities. What are the things I can imagine myself doing well into old age, and what would it look like to do those things when I’m 60, 70, 80 years old?

Writing feels like an obvious choice. But some time ago I realised the writing needed to become less frantic. More sustainable. And while writing might be compatible with getting older, the cadence of writing that is required to keep up with the internet, with the relentless churn of content creation, might not be. Writing every day is one thing. Trying to hit publish every day, or even every week, is not the way.

Skiing is a different challenge. I’m in the mountains of Japan again, and here it’s common to see people in their sixties and seventies skiing. Even older at times. These skiers might not be charging though the deepest snow or down the steepest slopes. But they’re out there having fun. Even if they ski shorter days. Take longer breaks. And spend more time warming up and looking after themselves.

Perhaps most of all I think about those going into old age mentoring, encouraging, and supporting younger people in their field. Generativity, the service of the generations that will take the work on once we’re gone, is a huge part of a happy and healthy old age.

The best first step in this is letting go of things. The competitiveness. The need for validation. The desire to the be the smartest person in the room. Or the urge towards self-reliance and independence.

By becoming lighter, softer, gentler and more open, we can be ready to face what will come, and help those around us along the way.

The post The Real Work Of Midlife appeared first on Fernando Gros.