Richard Buxton's Blog

November 26, 2024

Franklin - The Unheard Death Knell

//

// November 30th will see the 160th anniversary of the Battle of Franklin, fought in Middle Tennessee towards the end of the last full year of the American Civil War. As Franklin was a central part of my inspiration, I couldn’t let it pass unmentioned. Sam Watkins, a private in the 1st Tennessee, and fighting only a little way north of his home, wrote, ‘I shrink from butchery. Would to God I could tear the page from these memoirs and from my own memory.’

I attended the 2014 commemorations for the 150th; lectures, re-enactments, tours and concerts. Franklin is one of many American small towns that live with a civil war battle as part of their personality; Gettysburg, Fredericksburg, Sharpsburg, Perryville. Sadly, it’s not a short list. Some towns live with the history more easily, some less so. Franklin I would put among the former, at least in recent times. The Battle of Franklin Trust has steadily reclaimed small sections of the battlefield, as well as suppressing battle myths in favor of researched history. The homes of Carnton, the Carter House and Rippavilla are lovingly preserved. Franklin wants you to know its story. My first visit spawned the ambition to write the Shire’s Union trilogy (see Tigers in Franklin). The 125th Ohio comes full circle to Franklin, having billeted there in the winter and spring of 1863. There are so many lesser tales that live alongside the dominant story of the battle.

Why the battle took place here is a tale in itself. The Union’s General Sherman had taken Atlanta in the summer, some two-hundred and fifty miles to the south-west as the crow flies, deep inside the Confederacy. Despite the newly promoted General Hood’s attacks on his extended supply lines, Sherman determined to make the long march to the sea across Georgia and lay waste to the farms and industries that supported the rebellion. Rather than attempt to defend Georgia, General Hood set off in the opposite direction to try and recapture Tennessee and maybe even invade Kentucky. Strategically, it might have been the South’s last hope, but it was akin to abandoning your sheep to the wolves and taking your dogs off to hunt elsewhere. Hood might reasonably have expected Sherman to be forced to chase him, but by this stage in the war, the Union had a lot more men and many more competent high-ranking generals than the South. Rather than turn Sherman around, the Union command instead relied on General George Thomas to gather enough men to face Hood.

Hood didn’t take the crow’s route, instead shuffling along south of the Tennessee River until he eventually crossed his army at Florence, Alabama. General Schofield’s smaller Union Army of the Ohio fought to delay Hood rather than confront him, buying time for Thomas to gather his forces in the fortress city of Nashville. Hood tried his level best to head off Schofield and destroy him in battle, almost succeeding at Spring Hill. Schofield miraculously escaped on the night of November 29th, quietly marching by the sleeping camps of Confederates. Reaching Franklin early on the 30th, he quickly put up defenses while repairing bridges for his army to cross the swollen Harpeth River.

It was an angry General Hood that ordered the charge across the plains south of Franklin late in the afternoon. Some historians have suggested he was punishing his army for letting the Yankees escape at Spring Hill. Maybe, but it’s a strange general who would do that. More likely, he reasoned that an attack at Franklin was his last chance before the army facing him made it to Nashville to combine with Thomas. The last chance for him, and maybe the last chance for the Confederacy.

The Union army had barely a day to prepare, but prepare they did, and while there were some untested regiments in their ranks, for the most part they were seasoned veterans. Hood’s army was around 30,000 men, Schofield’s a few thousand less. The losses were not so evenly matched. Of the approximately 10,000 casualties, three-quarters were in Hood’s Army. Six Confederate generals were killed or mortally wounded, along with a huge proportion of unit commanders. All in just a few bloody hours. In terms of the numbers in the attack, the width of the front and the soldiers killed, the charge at Franklin was significantly bigger than the more famous Pickett’s charge at Gettysburg the year before.

For my characters, fictional and real, the day didn’t present itself as a morbid statistical competition with battles that had gone before. If you were in Hood’s Army of the Tennessee, many close to their homes, it presented itself as a forlorn charge to a likely death. If you were in Schofield’s Army, it was a desperate fight either side of sunset with your back to a flooded river, firing shells and bullets, thrusting bayonets and swinging rifle butts, for hour upon hour. If you were a citizen of Franklin, it was as if the very heart of the war, with all its blast and terror, had descended on your small town. It left almost every home a hospital. The injured and dead were beyond counting.

Arguably, the war was largely won in the West. From ‘62 to ‘64, Union armies steadily took Tennessee and Georgia while eventually capturing the full length of the Mississippi and cutting the Confederacy in two. And yet this climax at Franklin didn’t achieve the notoriety of the more fabled battles in the East or even of the great battles of Shiloh, Chickamauga and Atlanta in the West. Schofield’s Army left the town in the night over the reconstructed bridges, so the field was left to Hood. He was slow and inaccurate in reporting casualties back to his government. To his troops he represented it as a victory, but they knew it was anything but, and that their army had been gutted. Possibly, even the Union army was slow to realize the scale of the damage they’d inflicted, as were the Union press, though they roundly celebrated the victory at the battle of Nashville two weeks later. Hood had stumbled on that far only to face utter defeat and a long retreat through the December snow.

The term ‘the death knell of the Confederacy’ has been applied to more than one battle. When it sounded at Franklin, as surely it did, it largely went unheard except by those who were there. Today, if you trouble to go to Franklin, you can stand on the slopes of Winstead Hill as Hood did when observing the attack, or on the earthworks of Fort Granger, from where the Union rained shells on the wide rebel front. You can see where the Union Army escaped on the 29th near Rippavilla, visit the ordered Confederate cemetery at Carnton, and best of all, hear the story of the Carter family enduring the battle at the Carter House.

Shire’s Union

June 13, 2024

Deja Vu All Over Again

//

// I’m reading Whirligig and loving it! In fact, I plan to read my whole Shire’s Union trilogy back-to-back. How conceited is Buxton, you might be thinking, to read his own work and trumpet about it. But I’ve never understood those writers or actors who cringe at the idea of enjoying their own work. To be honest, I think most of them are putting on an act, self-deprecation or embarrassment judged a safer harbour than admitting they secretly read their back catalogue under the duvet with a torch. I’m having a ball, and I don’t care who knows it.

I do have a reason. The trilogy is on a blog tour so there are interview questions to answer, guest posts to write. The first book, Whirligig, was published in 2017 and I was drafting and redrafting it for many years before that. It helps to read it again and remember my inspiration at the time and some of the challenges. But I’d have read them all again anyway, because I adored writing them. To not do so would be like painting the last whisp of torn cloud above a stormy seascape and not step back and have a good look at what I’d wrought.

I’m old enough to suffer from a shaky memory, but it’s not always a curse. While of course I remember the essential plot, there are occasional walk on characters that I’d virtually forgotten and I get to smile and greet anew. Passages, paragraphs and dialogue that I can almost read afresh and enjoy. And there are particular pleasures that are only open to the writer: each and every chapter I get to remember the research as well as the writing. A few may have been entirely fashioned from the safety of my study, a synthesis of the history books on my shelves and the infinite rabbit warren we call the internet. But most were only completed after going to the setting, be it a battle site or a port, a river or a city. Reading it now brings to mind those places and the people I met. I’m prompted to remember moments of inspiration along the way. Some big, like finding my Whirligig in the Chicago Institute of Art, or standing in the Carter House basement in Franklin and realising for the first time the full story of the 125th Ohio, or holding a rough ingot of copper at the Ducktown mines. Others are tiny details worked into the novels, but delightful to rediscover. Like encountering a carpenter bee at Fort Donelson, choosing Matlock’s stolen china teacup in the basement museum at Woburn Abbey, or the shock of the cannon detonations passing right through me at the Resaca re-enactment.

And then there’s a further surreal interplay between my memory and the settings. Several times on research trips I’d encounter somewhere I’d not only read about but written about, so I had already tried to fully see it in my mind. The trip, in part, would be to make sure I’d understood the ground or the place I was describing. Sometimes that led to a correction, but other times I already had it perfectly. So it was like visiting a place I’d been too, similar to those weird déjà vu moments that we all experience that usually slide away or maybe you peg them to a dream. There’s a scene in Whirligig at the battle of Chickamauga where an army is in rout, driven in disarray up the side of a long open ridge. The battle site is almost entirely preserved in a national park outside Chattanooga. When I visited to check my draft and drove up to the viewpoint, I had such a powerful experience. As if I’d been there in some former life. There was no one around and I stepped out of the car and smiled and laughed. Now, in reading the scene once more, that memory waltzes with my earlier imaginings and my visits since. It really is déjà vu all over again.

Shire’s Union

January 4, 2024

Tigers in Franklin

//

// I couldn’t say how many Civil War regiments there were. It’s probably into the thousands, and I could have picked any one of them. So why did I plump for the 125th Ohio, Opdycke’s Tigers as they came to be known, as a home for my fictitious Private Shire? And how then did their glorious story – more fully revealed to me on a visit to the Carter House – bounce me from penning what was planned to be a standalone novel into writing a trilogy?

When I first conceived of Whirligig, it wasn’t ‘Book One of Shire’s Union’, it was just Whirligig. I knew I wanted it to be an odyssey of sorts: an English boy, Shire, obliged to join the Union Army and fight his way into the South to keep a promise from his childhood. So the regiment he joined certainly needed to be Union. I also wanted to include an event which fascinated me; the fight up Missionary Ridge outside Chattanooga, a spontaneous charge where the Union rank and file surprised not only the Confederates atop what was thought to be an impregnable 300ft crest, but also their own command who hadn’t ordered it at all. Any regiment I used was obliged to have fought on that day.

That narrowed it down considerably, but a quick count through the order of battle lists over two-hundred and twenty-five infantry regiments present for the Union that day. I set about finding a new home for Shire by going through the blue regiments one by one. I don’t think I’d tried more than a dozen before I hit the Tigers. It was love at first sight. Not only did they have a proud record, but also a wealth of contemporary sources. I quickly discovered the regimental history, Opdycke’s Tigers, by Charles T. Clark, Captain of Company F. He detailed not only the great battles but also the day-to-day life and events of the men in the regiment – so important to a historical fiction writer - from their formation in Cleveland late in 1862 to mustering out in 1865.

Better still were the letters of the 125th’s irascible colonel, Emerson Opdycke. Here was a civilian soldier with a hugely high opinion of himself (some of it justified) who had poured out his thoughts and experiences in letters to his wife, Lucy, which she’d preserved following his death and ultimately for Glenn V. Longacre and John E. Haas to publish in The Battle for God and the Right. They are wonderful letters, full of the sort of unbounded American self-confidence that fuelled the officer class on both sides. Perhaps only letters to a wife could be so shamelessly forthright. Sadly, Lucy’s letters back are lost, but I imagine in most of them she would have told Emerson to calm down, to stop putting the noses out of joint of officers and generals more senior than himself. Opdycke became my eyes and ears in the army. Well-connected beyond his rank, he would always know so much more than Private Shire who often needed to be a suitably disorientated hero.

The time came for me to fly across the pond and go to the places that mattered to the 125th in Whirligig. I’d planned a road trip from Chicago to Atlanta. An early stop was Dover, Tennessee, where as a green regiment the 125th arrived a day after a battle, in time to see the bodies still on the field. Quite a shock for Shire. Then it was on to Franklin where the 125th’s first ever action was to push Rebel cavalry out of the town in February of 1863. I was interested by their time there that spring, so well recounted by Charles Clark and Opdycke. How did Union soldiers get by in a largely Confederate town? I visited Fort Granger which the regiment had helped to build. Then I arrived at the Carter House. No Civil War buff can go to Franklin and not visit the Carter House. It changed everything for me.

At the time I knew very little about the 1864 Battle of Franklin except that Opdycke and the 125th were in the thick of it. The battle was, until relatively recently, not so widely written about as other battles less bloody or less critical to the end of the war. I took the guided tour of the Carter House and, standing in their cellar come dining room, listening to tales of Tod and the Carter family, it became clear as day to me that I had to write more than one book. I didn’t know then that my first novel would take three years to complete. Otherwise, I might have run screaming from the cellar. But I was hooked. After their time in Franklin in the spring of ‘63, the 125th eventually came full circle back to Franklin after almost two years of hard fighting further south. They were christened the ‘Tigers’ for their service at Chickamauga, fought their way up Missionary Ridge and right through the brutal Atlanta campaign, only to first shadow and then run from Hood all the way back to Williamson County, until they throw themselves into the climax of the battle at Franklin.

The trilogy, now complete, launched me on many other trips to the States, to all the battle sites where the 125th fought, to Trumbull County where the regiment was raised and where Opdycke is buried, to Johnson’s Island in Lake Erie where Tod Carter was held prisoner, back again and again to Chickamauga and back to Franklin. I never tire of it and thank my lucky stars that a cocktail of happenstance and serendipity led me to the 125th, and to the Carter House.

Shire’s Union

Reference books for the 125th Ohio Infantry.

Opdycke’s Tigers – Charles T. Clark – Spahr & Glenn – 1895

The Battle for God and the Right – The Civil War Letterbooks of Emerson Opdycke – Edited by Glenn V. Longacre and John E. Haas – University of Illinois Press - 2003

Yankee Tigers – Ralsa C. Rice – Edited by Richard A. Baumgartner & Larry M. Strayer – Blue Acorn Press 1992

Yankee Tigers II – Edited by Richard A. Baumgartner – Blue Acorn Press – 2004

December 6, 2023

Tigers in Blue - Closing the Trilogy

//

// On my laptop, the 27th of June, 2013, shows as the last edited date on the original draft of the first chapter of the Shire’s Union trilogy. Putting pen to paper (or more likely pencil to notebook) will have preceded typing the words into Word, so the effort will have started long before then. I couldn’t tell you the conception date of book one, Whirligig, though I do know that the trilogy was first imagined in the Carter House basement in Franklin, as far back as 15th May, 2011.

Suffice to say, that with the publication of the third and final book of the trilogy, Tigers in Blue, on the 8th December, 2023, Shire’s story has taken well over a decade to imagine, craft and refine. It’s a long time to live with my characters, real or imagined. And they haven’t wandered far since I dotted the last full stop. There are faces, vistas and looping scenes that live alongside my memories of family days out, of our three daughters (my non-fiction trilogy) of holidays and weddings. Chapters from the books are spliced with real memories of my visits to the places that mattered to the story, recollections of my trans-Atlantic jaunts themselves a little jumbled as I’ve criss-crossed Ohio, Georgia and Tennessee so many times. I visited Franklin, Tennessee, in the course of writing each book, central as it is to the trilogy which weaves in and out of the true adventures of the 125th Ohio. And Chickamauga, Georgia, draws me back every time I’m stateside, as do the never-ending ridges of the Appalachians, their fading horizons the inspiration for the book covers as much as they were for the stories.

There is a parting of sorts, though. I’ll never again sit down with the squad around their camp fire waiting for someone to tip the whiskey bottle, or drift with Tod down the Ohio River; no more journeys for Clara along the Copper Road; no more rides for Opdycke and Barney. But once in a while, recollected banter between Shire and Tuck will doubtless still draw from me a smile or an inner chuckle, as if they were old friends of mine. I guess they are.

Shire’s Union

June 25, 2022

Back with the Tigers

//

// The stop wasn’t on my itinerary, but I find my way here nonetheless. It’s four years since I was in America and eight years since I was at Chickamauga in the very north of Georgia, just across the Tennessee line from Chattanooga. I’ve finally made it out to check details for my third book, Tigers in Blue, the last in the Shire’s Union trilogy. The battle of Chickamauga is the epicenter of the first book, Whirligig. It’s where the 125th Ohio were christened the Tigers. This place matters to me, but I still wonder at being drawn back here.

My itinerary took me on a clockwise loop out of Nashville, on to Knoxville and then down to Decatur in Alabama, where the fastest route was via Chattanooga. Why not stretch the extra ten miles south and overnight close to the battlefield? It would be rude not to. I’d digitally booked my motel at short notice and gone bargain basement to keep down the trip cost. It was mostly basement. They had no knowledge of the booking, but there were a couple of rooms left. There was a comical series of visits to the desk to get in, get a cleaner room, understand the wi-fi code (3 trips) and finally to confirm would they like the fridge in my room left open to defrost, as I’d found it? It didn’t affect my mood. I dined at Sonic Burger and looked forward to walking the battlefield in the morning.

The weather had been in the nineties so I’m out early. There are more deer than dogwalkers out under the low sun. Aside from one 30mph state road and the smaller tour roads themselves, the battlefield is more of less as it was. Though there’s an argument to say it was even more unspoiled before 120,000 soldiers turned up to do battle here in September of 1863. The Widow Glenn, whose tiny house was commandeered as a headquarters and burned out during the fighting, would certainly have thought so.

Familiar with Chickamauga, I have no particular agenda and just enjoy the time. Like visiting an old friend. I find my way to the places that mattered to the 125th, but otherwise let my mind wander. It gets extra roving privileges in a place like this and I begin thinking on my connection to both here and to America. But for Covid I would have been here two years ago. Despite all the changes in the world, America seems to be having the same arguments as when I was last on this side of the pond (this based on my scientific sample of news outlets and talking to strangers in Nashville bars). It’s still Trump vs the establishment, race-relations more than ever, still the gun lobby verses the glaringly obvious (just a different school massacre). We have our own protracted issues in the UK, some very similar, and it makes me think how poor we are in our western societies of actually reaching a point of decision. The arguments have long since taken precedence over solutions. Exhibit A: Our clown minister was recently pictured raising a glass and toasting a room full of other drinkers on a date where he had confirmed to parliament that there was no illegal party during lockdown. After seeing the photo for the fiftieth time that day, I watched a news anchor proceed to ask the question, ‘Did the PM therefore lie to parliament?’ Well, yes. Of course he did. You just showed the proof! He’s bang to rights. Yet we’re now so trained to consider the other point of view that we’ll entertain it even if it’s plainly false and patently ludicrous. Whole nations are now confidently basing their propaganda on the fact that western media will listen and broadcast lies as often as you want to tell them. No decision, no move forward.

Maybe it’s why I find history is so attractive. We can debate on the finer points, but for the most part it’s a done deal and you can see the outcome. Chickamauga, in and of itself, settled little, except for the 37,000 men killed, wounded or missing. But put together with the thousands of other civil war engagements (mostly not on Chickamauga’s scale) two things that mattered were decided. The Union would be preserved, and state-sanctioned slavery would end. Given the war cost an estimated 750,000 lives, it makes you wonder if a little prevarication is such a bad thing. As a decision-making process, war is clearly flawed. But decades of arguments, compromises and elections failed to deal with the fundamental wrong of human bondage.

The historical resolution I enjoy while walking the gentle slopes, touching the cool stone of the monuments, finding a bird’s nest in one of the cannon, is all from a safe distance. During the long years of the war, people would have been as we are now. More so, in fact. Frustrated, frightened, angry, wanting the world to move on. When I leave Chickamauga for the three-hour drive down the Tennessee Valley to Decatur, I avoid the news channels and listen to sport instead, something else that usually ends in a result. Unless it’s cricket.

Disaster Emergency Committee – Ukraine Humanitarian Appeal

Shire’s Union, books 1 and 2.

March 5, 2022

I can't Imagine

//

// It’s an unsettling time. The true meaning of that depends on where you live. For me, in England, every time I think about the news, my gut feels like it’s been dropped from the white cliffs of Dover. In Ukraine, it’s more literal. They are giving up their homes, losing their lives, facing bleak choices we’d believed consigned to the last century. It forces me to ask, why write about a war in America that started over one-hundred and sixty years ago? There is war now.

My workshop group met this week and my contribution was a chapter from Tigers in Blue. I’ve just completed the second draft of the final novel in the trilogy. When I sent them the chapter to review, Europe was still at peace. Two families have to think whether to stay or leave as Hood’s Confederate army crosses into Middle Tennessee and sweeps north. Their emotions are difficult, for each a mess of attachments to people, to place, to their own tangled pasts. Of course, as a writer you go hunting for those emotions, set scenes where they are most raw and exposed. What to leave and what to load in the wagon, a tearful farewell at the end of the drive, the sound of the first cannon in the distance. I’m attached to my characters, and in writing about those partings – some which I know to be fictionally final – I might get a little watery eyed. It’s all so safe from one-hundred and sixty years away.

I don’t have to imagine those scenes any more. I can watch them every day. Ukrainian men in Krakow, saying goodbye to their families and climbing onto an air-conditioned bus to go and fight. A bewildered mother with her children stepping down from a twenty-first century train in Berlin, nervously approaching a couple who hold up a sign: Room for three. Stay as long as you need. The forlorn wagons that clogged the river crossings in Tennessee are replaced by Hondas, Volkswagens, Skodas, but they’re still more composed of desperation than hope. In 1864 the Confederate government passed its third conscription act, for all men aged seventeen to fifty. The war was three years old by then. The Ukrainians asked men 18 to 60 to stay and fight within a matter of days from the Russian invasion.

Many people tried long and hard to avoid the American Civil War. They really did. It had been lining itself up for decades: conflicting vested interests, misaligned hopes and dreams, juxta opposed views of what constitutes a human being. In the end, those differences firmed up on either side of the young states’ borders and the fighting began. I’m not so sure the current war was as inevitable. It’s rooted in one sour man. We shouldn’t beat ourselves up over our incredulity that war could come to Europe in this century. That was a view based in hope. Where would we be if we planned based on despair? We should know evil when we see it though, whichever century it’s living in.

The workshop group were positive about the chapter, my friends citing how it chimed with the here and now. I’d rather it didn’t. I’d rather be left with the challenge of evoking the past, summoning it ghost-like into the reader’s mind to fade gently away when they close the cover and go about their peaceful lives. I’d rather be left to imagine.

Disaster Emergency Committee – Ukraine Humanitarian Appeal

Shire’s Union, books 1 and 2

August 8, 2021

Writing from the Soul

//

// In modern, popular culture, the word soul is used at least as often in its musical context as it is for considering an eternal life beyond the earthly realm. The idea of a soul, the precious core of our being has, in many places, fallen out of fashion. But I would argue that, regardless of your religious outlook and what you write about, taking the time to consider the wellbeing of your character’s soul can lend extra depth to your writing.

I’ve completed the first draft of the last book of my Shire’s Union Trilogy. As I approached the last few chapters it became increasingly emotional for me. Not only was I looking to complete story arcs for Tigers in Blue, I was also finishing the character arcs that span all three books. I have spent eight with some of these characters. Their outcomes matter to me aa great deal. Not all of them have made it this far. Whether or not those remaining survive to the end of the story, I have to do my best to understand their state of mind this far into the war. For my real historical characters that means working with what can be gleaned from the historical record and putting myself in their well-worn shoes. For my fictional characters, it feels just as important to be true to the people – to the souls – I have created on the page.

Of course, to most people of the mid-19th century, looking after their soul would have been a daily preoccupation, as natural as we today might look to eat well or to exercise. Prayer and religious service, in preparation for the life to come, would have been part of their routine as it still is for many. Life was seen as a burden or a trial for what was to come, and here was a civil war – an extreme time. For the soldiers, death was a daily companion, whether from conflict or more often disease. Civilians could see their towns burned to the ground or find the aftermath of a battle left rotting on their doorstep. They lived in constant fear of a fateful letter arriving to tell them a husband or son was dead. It was a time of great displacement. Homes were lost, lives were inverted. Living such a precarious existence, my characters would have an overt and spoken concern for their souls. I intend to reflect that as I review my first draft and begin the enjoyable process of revising the novel.

Understanding how they would act and what they would say is part of what we do as authors, but beyond that, I believe that consciously considering the health of every soul can allow a writer to reach deeper into their characters. Whether you think of the soul as a concept or as a real thing, it allows you into the core of a character, to their essential self, to the centre of their shaped being from where they look out onto the world. If you can touch that as a writer, then you’re about as fully in their perspective as it’s possible to be.

All stories are about how people are changed by their life-experience. Without change, there is no story. My characters have been in a vicious, fratricidal, all-enveloping four-year war. None of them can remain unaltered. They have buried friends and family, lived through the chaos and bloodshed of battle, gained love and lost love. If they were the same people at the end of three books as they were at the start, then I’d be a poor writer. Shire, my main character, has steadily amassed a collection of physical scars. He has a tear shaped burn on his cheek gained from a riot in New York; a pink dot on his chest from a spent bullet at Missionary Ridge; a healed wound in his calf taken in the winter of 1864. But what are his scars on the inside? Today we might talk about mental health or PTSD. Back then they might have talked about a wounded soul. How much of the simple-hearted boy who left England is left when Shire lines up for his final battle? By this time, the soldiers were exhausted, both in body and spirit. Some were no longer prepared to fight, too damaged to face going home even if they could. Others were prepared to throw themselves recklessly into death rather than survive a lost war. People were shaded toward good and toward evil. None were unscarred. They had come to know both the savage and the better angels that live in men’s souls.

Shire’s Union, books 1 and 2.

April 2, 2021

Once more unto...

//

// It’s not easy writing battle scenes (as Kermit might sing). They are a crisis in the story; possibly the piece of history that inspired the book; the climactic moment of danger for the characters I’ve sent into the breach. I’ve reached this point once more while writing Tigers in Blue, my hands held anxiously above my keyboard, like a soldier with an itchy trigger-finger before the charge. Well, sort of.

There’s a danger as a writer when you hit the action button. It’s as true of suspense or horror genres as well as historical fiction. You’ve spent fifty-thousand words crafting your characters and their story arcs, intertwining their lives, getting the reader to love them or hate them or both. You’ve even managed to set up the visuals, subtly familiarising the reader with the setting where it’s all about to kick-off. The tension is at breaking point. Then you describe one googly-eyed monster or get lost in the blood and guts and everything dissipates in the unreality you’ve just described.

At a line-by-line level it’s hard to portray an epic battle without falling back on the same descriptions. There’s only so many ways you can say bang. The tenth time you talk about ‘sheets of flame’ or the ‘thunder of cannon’ it ceases to have an impact. A good thesaurus helps. I spill words onto my whiteboard from historical accounts to fit in as and when they suit. And I’m constantly reaching for a new way to describe using emotion that will connect, or detail that will engage, the reader.

You might think the solution is to describe it as it really was, and certainly that’s always been my intent. But there are problems there too. For a start, how the hell would I know? I’ve done my best. Flown to battlefields, dressed up in Union blue, camped under the stars, learned to load and fire a Civil War rifle, chased Rebels through the woods. I got pretty excited in a twelve-year-old sort of way. But I never feared for life or limb, never watched my friends bleed out. And there were only a few dozen of us… Also, if described how it really was, I’m pretty sure my main character Private Shire would have next to no idea what was going on, not in the smoke and the chaos and the hand to hand fighting where his universe is the man in front who’s trying to kill him. If you attempt and give a broader view of events, some level of detachment can sneak in. You have to be inventive. Find moments for characters where the big picture is on show and then zoom back in to their immediate world.

I’ve read no end of personal accounts but annoyingly, when it comes to the real nitty-gritty, they often use words like ‘indescribable’, or say that the ‘vivid impressions and terrifying scenes were indelibly stamped on the minds of the participants.’ It’s understandable why their minds may shy from the detail, but it doesn’t help me get to the reality. Do readers even want the true reality or would they rather look away or watch with one eye closed?

Ethically, you can tie yourself in knots. I’m writing about real events, sometimes using characters who lived through these extreme moments in history and a fair number who never made it to the other side. Do I know how they felt when they got up for breakfast that day, as they got into line, as they killed or were killed? In some cases, I’ve spent years with the ghosts of these people. I’ve visited their homes and their graves. I owe them a debt of respect. I want to get this right.

In the end it comes down to best endeavours and trusting my imagination. If I’ve done all I can as a life-long civilian – removed from the time I’m writing about by a century and a half – then I’m as prepared as I can be to step off into my personal writing battle. You have to turn it around. I’ll likely get some things wrong, but by entering their world, portraying the sort of challenges they faced, trying to reach for their possible emotions, I am honouring them, becoming a part of the collective effort to understand.

I must go. The trumpet has sounded, the flags are unfurled and waving high. The first cannon has boomed!

Shire’s Union, books 1 and 2.

Battle Town (short story)

January 18, 2021

I Beg to Differ - Local Thinking on the Cumberland Plateau

//

// I beg to differ. You don’t hear that term so much these days. A polite apology for having your own point of view and asking if you might offer it up. We’re more likely to stridently announce how someone else is a hundred percent wrong, or maybe never listen to what they have to say in the first place.

I’ve started many posts in the last year saddened by events in the U.S.A. and then predictably found some pretext to relate these to America’s history. What can I say; I’m drawn to it. I find history fascinating for its own sake but it’s of little use if we don’t explore parallels to now and what lessons we might learn. It’s also unavoidable when you’re alternately reading about ante-bellum or Civil War America and then watching the Capitol stormed on the evening news.

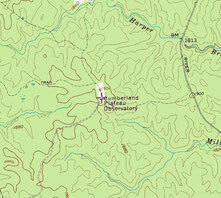

American Civil War histories can be on the grand scale of the demi-continent it was fought over or more precise and localised in their focus. A good friend of mine sent to me across the pond Aaron Astor’s book, The Civil War Along Tennessee’s Cumberland Plateau. The plateau is a sudden rising scar of mountains and high valleys that angles across the state, running from west of Knoxville down to west of Chattanooga. Astor draws out wonderfully how the geology and soils of the region shaped settlement, people’s outlook and eventually allegiances when it came to war. I’ve driven over the plateau many times but never stopped outside of an interstate rest area. It’s impressive. The land-trains struggle up and burn their brakes coming down. It was an encumbrance to the Civil War armies too. I set a scene in Whirligig where the Army of the Cumberland is making heavy weather to get their wagons and artillery across.

It was similarly a barrier to settlers steadily moving west in the first half of the 19th century. Having taken decades to seep through the gaps in the Appalachians, the Cumberland Plateau was the next serious barrier beyond the upper Tennessee Valley. The Cherokee were pushed steadily back to the west and eventually expelled from the region altogether by President Andrew Jackson. The soil on the plateau was thin and rocky for the most part, so tended to attract those with little money and few options. In short order the settlers were converted into semi-subsistence farmers who scratched out a living, highly dependent on their neighbours in time of need. Communities often centred on high, small valleys known as coves, many with only one road in and out. Astor describes how the harsh environment was reflected in evocative place names: No Business Creek, Brimstone Creek, Devilstep Hollow.

News into and out of these communities was limited in the early decades of settlement, often only brought in by merchants then passed on by word of mouth. The political tone or spin was often set by the self-interest of the local elites. Over time the isolation broke down to some extent. Turnpikes were built across the plateau and county politics began to live alongside the leading families’ power and influence. However, by the time secession and a probable civil war were on the ballot paper, the scattered populace’s outlook was still so heavily localised that in many cases neighbouring counties voted heavily in opposite directions; some to stay in the Union, others to side with the Confederacy. Tennessee was the last state to secede on June 8th 1861, largely due to the votes of bigger population centres in Western Tennessee. The result for those on the plateau were long years of bitter local fighting, a war within a war, fought almost privately in the mountains.

I’m greatly simplifying Astor’s wonderful history. History and societies are far more complex. And where’s the parallel to today, you may ask? Surely in the modern world we are broad in our outlook, all knowing in our perspective.

I beg to differ.

The Cumberland coves were carved over hundreds of millions of years, ready to hold and shape communities in isolation. Now, I’d suggest, we’ve got busy in recent decades hollowing out virtual coves in the pioneer wild west of the internet. They are carved by algorithms, watered by self-reinforcing social media, and ready to be preyed upon by ‘elites’ that are not local but far away. They distance us from our near neighbours better than any mountain or high forest. And not just in Tennessee. Across America and across the world, whatever our persuasion, we’re listening only to those who tell us what we’ve become accustomed to hearing. I see it in my friends and I see it in myself.

The current international and local isolation doesn’t help. But maybe when the siren sounds and I’ve finally hugged my distant family and absent friends, I’ll find a bar, pick a stool, and start a friendly conversation with someone who I’ll be pleased to disagree with and might return the favour.

The Civil War Along Tennessee’s Cumberland Plateau - by Aaron Astor

By Richard Buxton

Battle Town (short story)

November 26, 2020

The Ghost of Christmas Past

It was Christmas Day in 1860 and Lincoln, newly elected president but yet to

be inaugurated, was at home in his reception room in Springfield, Illinois. The town was busy. Christmas was not a public holiday. He was trying to cope with a mountain of mail and a constant

flow of visitors who were mostly there for their own interests rather than his. South Carolina had seceded five days ago. Civil War loomed, although the first shot wouldn’t be fired until the

spring. Amongst the gifts he received from complete strangers this day, was a whistle fashioned from a pig-tail. The sender claimed he’d crafted it just to show it was possible. I can imagine it

appealing to Lincoln’s earthy sense of humour. It probably got more attention from him than his more expensive gifts.

The four Christmases to follow would all be in wartime and every one of them

would see fighting. Lincoln would be dead before the next peaceful Christmas, along with around 650,000 other Americans, North and South. The war to come would change many things, including Christmas. For decades, even

centuries, before the war, European Yuletide traditions had poured into America along with variant nationalities and religions. American practices at Christmas largely paralleled those in Europe.

In the same way they followed hat styles in Paris, they adopted Victorian/Germanic fashions in Christmas trees, decorations and cards. Being American, they added a flare for commercialism that

left Christmas never quite the same again.

To understand the wartime development of Christmas, you need to consider how

the Civil War more widely shaped American identity. What it means to be American has never truly been a constant. It didn’t arrive fully formed with the Declaration of Independence. At the

outbreak of war, America was just eighty-five years old. In those years it had never stopped changing and reaching westward, a constant flow of immigrants stirring the pot. Now here was its

greatest crisis, a civil war, where the question of what it meant to be American, what the Union represented was a matter of life and death. And here were men and, to a lesser extent,

women, thrown together in great armies: English, Scots, Welsh and Irish, German speakers, the Dutch, eastern Europeans; all away from home and all lonely. Any commonality in Christmas traditions

really mattered. It helped comfort them but it also gave them a seasonal rallying point in terms of what it meant to be American. The Civil War re-asserted and to some extent reconstructed

America. Christmas traditions were a brick in that reconstruction.

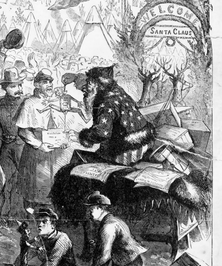

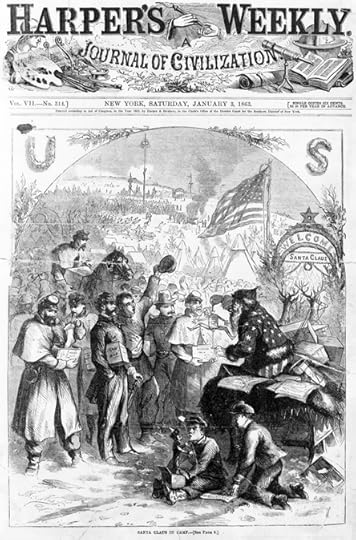

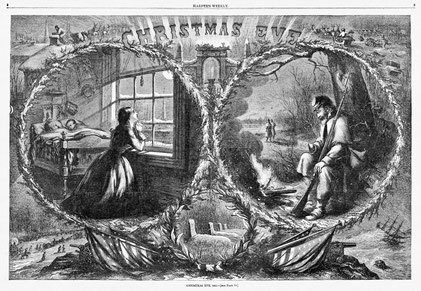

You’ll want some proof. Here goes. The first depiction of Santa Claus, as we

might recognise him today, dates from the Civil War. It’s true. During his campaign for president, Lincoln hired an illustrator to produce his posters. The artist was called Thomas Nast and, late

in 1862, he was asked by one of the most popular periodicals of the time, Harper’s Weekly, to produce their Christmas cover. Knowing Nast as he did, Lincoln himself is rumoured to have proposed

the idea of Santa Claus visiting Union troops. Santa Claus appears in the stars and stripes, but he is the same white-bearded, rotund, non-chimney-shaped old fellow that we see in shopping centre

grottos to this day. The genius of the image was that it mixed tradition with patriotism at a time the Union war effort was at a low ebb. The cover was so popular that Nast got repeat commissions

from Harper’s Weekly for many Christmases to come.

Christmas on the frontline wasn’t quite as joyous as Mr Nast was

implying. A Union army was camped to the south-east of Nashville. A Confederate army was close; just a little way down the road to Chattanooga. Battle might come soon. The weather had been clear

and mild but Christmas Day it was overcast. Santa Claus, represented by the postal service, turned up for some, usually with food parcels rather than presents, but many would get nothing at all.

Peter Cozzens, in his wonderful trilogy on the Chattanooga Campaign, describes a festive season for the officers, especially the Confederates, as they were on home turf and supported by the local

citizenry. Elaborate balls were held, the halls decorated with cedars, evergreens and captured battle flags. The Union army had to work harder for dance partners; the Fifteenth Wisconsin put two

of its soldiers in drag for a party at the local schoolhouse.

Away from the more organised festivities the soldiers played dice, held

chicken fights and the whiskey flowed freely. Food was a preoccupation every day of the year and not just at Christmas, but some made a special effort. Johnny Green of the Ninth Kentucky headed

out into the country in search of a turkey. He found eggs and onions but had to settle for a goose. He baked a poundcake and, being teetotal, settled for a quiet meal. Colonel John Beatty of the

Third Ohio did a little better. Back in Nashville he acquired a turkey for a dollar and seventy-five cents, but, he said, ‘it lacked the collaterals, and was a failure.’

Beatty’s disappointment with his attempt to honour the day was more in line

with the general mood. Melancholy ultimately won out over Yuletide cheer. While Christmas Day offered soldiers a brief escape from the daily grind of army life, it was also a pointed reminder

that they were far from loved ones. Many chose to spend the free time they had writing letters home or, seated around the campfire, recalling earlier and happier Christmases. Many would only be

ghosts at Christmases yet to come. Over New Year three-thousand would die at the Battle of Stones River.

Things were little happier at home. In a novel written shortly after the

war, Louisa May Alcott describes how her ‘Little Women’ woke to find no stockings hung in the fireplace, but a bible under each pillow. The absence of, and concern for, Father, is a constant

through the whole day. In the South children were even harder done by. The Union Navy had blockaded all the ports, basic foodstuffs were exorbitant and most presents would be homemade. In a harsh

move to manage expectations, General Howard Cobb’s children were simply told that Santa Claus had been shot.

Lincoln spent the four wartime Christmases in the White House and for the last

received a present much larger but every bit as odd as his pigtail whistle. General Sherman, having devastated much of Georgia, telegraphed Lincoln. ‘I beg to present you as a Christmas gift the

city of Savannah…’

Nast would continue his Harper’s Weekly cover pictures long after the war.

Christmas traditions in America, solidified and somewhat unified by a new sense of what it meant to be American, would endure. But this wasn’t the most telling change in Christmas celebrations.

Before and during the war, enslaved African-Americans only enjoyed Christmas at the whim of their ‘benevolent’ masters. There may have been extra leisure time, better food, parties and even

permission to travel to visit relatives. No doubt the slaves made the best of what was granted to them. The most profound change in the celebration of Christmas brought on by the Civil War was

that in 1865, after the total Union victory, four million former slaves were free to make their own plans for Christmas.

CHRISTMAS SALE! Whirligig and The Copper Road eBooks will be on sale via Amazon from December 4th through December 11th.

This article was originally published as a guest post entitled ‘A Civil War

Christmas’ on Mary Anne Yarde’s Coffee Pot Book Club in 2017.